Volkan Alkanoglu was educated in Germany and England and worked as a designer and project architect for Foster + Partners, Future Systems and Asymptote Architecture before establishing his own practice ‘VA DESIGN’ which is now based in Boston. In 2006, Alkanoglu was nominated for the Young Architect of the Year Award in the UK, in recognition of exceptional contributions to the progress of architecture. He offers an explicit international background and has contributed to building and research in the field of architectural design and sustainable projects. Recently, Modelo had the opportunity to meet with Alkanoglu and learn more about his practice and approach to design.

On becoming an architect

I started out as a civil engineering student at the RWTH in Aachen, Germany when one of my friends studying architecture asked me to join him at an evening lecture at their department. I was mesmerized by the talk and what architecture could be. They started showing incredible images about details, materials and how people occupy space — it was quite amazing. The very next week, I started applying to architecture schools and ended up at the Peter Behrens School of Architecture in Düsseldorf. Upon graduation, I moved to New York and worked for a small boutique firm until 9/11 happened. Obviously, everyone’s life changed drastically during these times and I decided to return to Europe where I enrolled in the Masters program at the Bartlett School of Architecture in London.

“Jetson” (Photography by Patrick Heagney courtesy of VA DESIGN)

On his post-grad experience

The education at the Bartlett for me was all about establishing your own design principles and translating your conceptual ideas into physical production, meaning — a lot of drawings! I was fortunate to be surrounded by incredible peers and often look back to those days for inspiration. Sir Peter Cook had setup an exceptional curriculum within the graduate program. There was a lot of determination, enthusiasm and drive amongst the cohort in our Master’s class, yet the atmosphere was also collegial and supportive. Everyone was doing strange projects such as: atomic craters, floating bubble environments, and cooking machines, much in the spirit of Archigram. It was liberating to revisit architecture through a completely different lens beyond the modernist paradigm I had been taught in my undergraduate studies. We were able to craft and visualize our take on architecture in a very experimental fashion. Maybe this is why a lot of us got involved with academia and are now teaching at the AA, Columbia, Bartlett, SCI-Arc and many other places.

Upon graduation, I started working for Foster + Partners in London. Everyone back then was somewhat affiliated with one of the many British hi-tech firms such as Grimshaw, Hopkins, Rogers, Future Systems, and Zaha Hadid etc. Foster + Partners was an important experience in my early career because it is a highly reputational firm having produced a vast amount of canonical buildings and probably deserve more recognition here in the US for their contribution to the discourse in architecture. Projects such as the Willis Faber & Dumas Headquarter in Ipswich and the Sainsbury Center for Visual Arts in Norwich have very much pushed the boundaries of building typologies (Office+ Mall and Shed+ Museum) and introduced a symbiotic relationship between technology and performance within architectural design. At Fosters, I was surrounded by many experienced architects. As a young graduate, it’s the perfect place to be, since there’s always someone you can learn from.

Immediately, I found myself in charge of my first project. It was to update the interior of the London City Hall with new security systems. It’s not necessarily as creative as planning a new building and there wasn’t much design involved, but it was rather all about collaboration, being efficient and coordinating a team of consultants. There was a lot of logistics for me to master while moving in and out meetings all day, and constantly corresponding via phone and emails to clients, structural engineers, civil engineers, environmental engineers, cost consultants, fabricators and so on.

This challenge of being pushed into the realm of professionalism was pretty challenging because suddenly I went from designing Sci-Fi robots at the Bartlett to specifying X-ray systems, ordering stainless steel alloy, or making sure that building codes are met. It was interesting to be thrown into the deep-end and then slowly learn how to move forward. There were a lot of processes I picked up during that time which are very beneficial for me now running my own practice.

“Ines Residence” (Photography by VA DESIGN)

On starting his own firm

I worked for others with the ambition to absorb as much as I can about delivering design projects and how to run a practice. After working on countless competitions, flying for project meetings around the world and delivering presentation after presentation you really absorb a lot of information about the game of architecture. After experiencing this on a day-to-day basis for many years, I finally decided to start my own practice. In addition, the opportunity to teach at SCI-Arc in Los Angeles enabled me to split part of my time in academia while also focusing on my professional work.

It’s a leap to go out on your own because many people do not trust you as a young designer. It was difficult for me to get clients right away and I had to generate my own projects, which mostly don’t pay anything. I started to enter open competitions and was fortunate to win some of them, and slowly generated some revenue and received follow-up commissions. For example, I was one of 10 people out of over 400 selected as part of the Sukkah City Competition in New York City. There was a lot of publicity around the project back then in magazines, newspapers and the many visitors it attracted at Union Square Park during the exhibition. Our pavilion is now part of the permanent collection of the Jeshiva Jewish Museum in Manhattan. (It was literally carried down the street by 4 people to the front door of the museum from Union Square.) After receiving this kind of exposure a potential client called me up and said “We love your project, can you do something similar for us?” which led to two consecutive projects in Miami.

On how his approach to design has evolved

The design work constantly evolves due to the new experiences, mistakes we make and learn from, and a continuous engagement in the discourse of architecture. I have a strong interest to work on projects which challenge the discipline, or in other words, projects which deal with performance and cultural issues. I can’t say that every project of ours incorporates those ideas, but I am trying to further approach our design work with this ideology. Some current projects are about rethinking typologies, which can be even as simple as designing seating. We did a bench, called ‘Public Figure’ in Miami. Typical benches are usually linear where people sit down and face forward. There is not much interaction between the people who share the bench, which is partly why strangers don’t talk to each other. We designed our bench to take on a circular figure. Suddenly, users look at another person and there could be some informal conversation or discussion which can trigger something unexpected. Architecture is very powerful in that way and that is something I really appreciate; when the design has an influence on how people behave in a space and interact with one another.

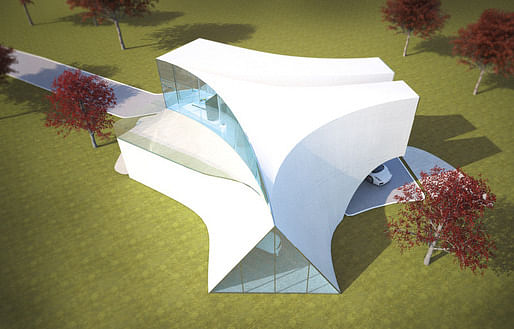

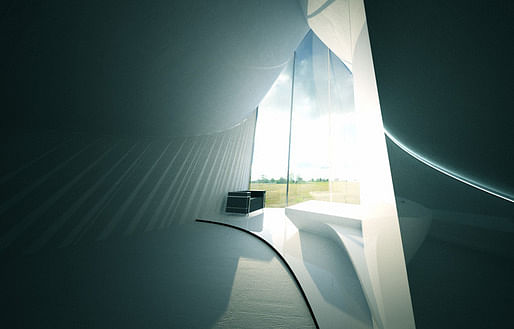

“Park Residence” (Photography by VA DESIGN)

On tools and limitations

Software and tools are widely accessible now to the majority of our profession. There are more and more plug-ins and codes being introduced not just by larger companies, but by the everyday user and through open source networking. These new platforms are developing very fast and focusing on solutions for very specific problems. We can also now handle larger amounts of ‘Big’ data and according to Mario Carpo, this has an influence on the aesthetic and production of the global design work in general. You can handle millions of surfaces now in modeling, when it was more limited before due to software and computer capacities.

However, any new developments in architecture are usually very slow to make an impact. We are working in a profession which does not adapt very fast to the notion of change. Our clients have the latest smart phones and gadgets but this attitude does not necessarily apply to the way they think about the built environment. Architecture is overall more complex.

In terms of the application of tools, when I was working for Asymptote Architecture in New York, I was running projects with up to 15 consultants. Our methods of delivery, tools and communication were crucial to the success of those projects.

The projects we are working on at the moment in my own firm have a moderate size, so it’s not that we’re dealing with a skyscraper or a masterplan where some of the specialized tools or shared platforms are necessary to be efficient and productive. We usually pick the tools we require for the given task and are very open to look into new opportunities or alternative means of communication if necessary.

The limitations I have had thus far are with the translation of our tools to consultants and fabricators. So, if I talk to someone about production, I have to make sure we speak the same language. Sometimes our tools don’t communicate the same way and then we have to shift our means of delivery until there is common ground. Miscommunication usually ends up in costly mistakes, however maybe there is a potential for these misunderstandings to produce something extraordinary instead. Architecture is very much about control and semantics most of the time.

“SubDivision” (Photography by Brooks Dierdorff courtesy of VA DESIGN)

On his philosophy to architectural design

My current work is multi-faceted with focus on performance, building typologies and material studies through architectural installations within the public realm. We just installed a project called ‘Super Nova” in an atrium space at the University of Colorado in Denver with commissions for upcoming projects at the Fort Lauderdale Airport, San Francisco, and Durango. In addition, I am also currently pursuing research at the intersection of the electric automobile, the garage and domesticity.

Throughout history, several architects have considered the relationship between the automobile and the building within architectural experimentation. After the construction process was completed for each project, Le Corbusier insisted that all of his buildings were photographed with modern automobiles staged within the frame. This controlled representation of his work, projected an idea that the house was to be viewed as modern machine and as similar iconic imagery. Both the automobile and construction industries have missed out on the opportunity to engage each other on these polemical issues within our cities.

Recent technological developments such as the electric car and driverless car enable opportunities between these two long-lasting modernist paradigms. There is a potential for new building typologies in conjunction to performance and programmatic use. It is a very exciting topic to work on and if we imagine the “Futures” of our domestic homes, we must collaborate with other disciplines. The research being produced in the car industry is fascinating and I can see a lot of overlaps towards architecture.

A few of our current design projects such as the Auto Residence or Park Residence are taking on this troubled relationship and explore possibilities for future living environments. The Auto Residence, for example, questions the status of the garage as we know it. We are speculating for this space and everything attached to it, to take on a new programmatic role. Does a self-driving electric car really need a garage? Can it take on other programmatic usage and rather be part of the house? We now have the unique opportunity again to rethink the prior troubled, relationships between architecture and the automobile.

“SuperNova” (Photography by VA DESIGN)

On the SuperNova Project

The SuperNova project is part of a lineage of research projects which are all technologically driven at the moment. These ideas are more about synthesizing structure and material. How can you design something to be paper thin and superlight while maintaining its structural integrity? The first project was installed inside an atrium at the University of Oregon and weighs only 60 pounds. The second project is almost double the size with a volume of 14 feet by 20 feet by 6 feet and was installed in Atlanta this year. It weighs only 80 pounds and was fabricated out of super thin aluminum similar to a Coke can.

We are learning with the development of each project and are able to create a feedback loop. This way we are able to continuously incorporate improvements and make our design work more efficient. The SuperNova project is now the third built installation of this series, this time undertaking new structural logics. We are developing a fourth project with this research in San Francisco by the end of the year which is going to be installed outdoors, so we will face totally different challenges.

While we are interested in the design of these installations, we see them more as prototypes for larger projects which also deal with constructability, materiality, and economic feasibility. The goal is to take the knowledge gained from this research and apply it to larger architectural projects.

On advice he would give himself before starting

As Sir Peter Cook used to say to us: “If in doubt, put more lines…”!

At Modelo we want to know what drives the world’s design and architecture talent. This is why we invite select architects and designers to share their stories, philosophies, visions and favorite works with the public — their manifestos. For more information on how we're working to change the architecture and design world at Modelo please visit us at: www.modelo.io.

1 Comment

Great article.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.