Mesa Verde

This past fall, I took an extended weekend to go see the ruins at Mesa Verde. I am just now getting caught up on all my personal projects and essays, so with that, I bring you this.

Mesa Verde is a series of cliff dwelling spread throughout the Southwestern corner of Colorado, they were constructed by the Ancestral Pueblo peoples around 1200 C.E.. This is my second trip to Mesa Verde - I can remember scampering through the doorways of many cliff dwellings as a child of 8, however since that clearly preceded my architectural education, it was nice to head back. I also now have the privilege of a rich context in which to place the ruins. Pre-Columbian archaeology has always fascinated me. I enjoy the mysticism of tracing human occupation in the Americas and appreciate archaeology as more than just the origins of architectural drawing and much of renaissance thought. I always stop for archaeological ruins as I travel (and skateparks), and it was pleasing to be able to view Mesa Verde after having seen many of the most significant archaeological sites in the Americas including Machu Picchu, Chichen Itza, the Natchez Burial Mounds, and many smaller sites throughout the Americas. Seeing Mesa Verde as a child, before seeing these other sites, was a transformative experience, but seeing the cliff dwellings with the experience and knowledge of world travel made that previous experience all the more incredible.

We headed out of Denver late Thursday evening, drove to a campground and crashed. My approach to National Forest Lands is kind of like Fugazi’s approach to ticket prices - pay what you can. Of course, only paying two thirds of the camp fee had my wonderful girlfriend on edge, so we headed out at dawn to drive the remainder of the distance. Our route took us past Highway 149 to Creede where I worked for 8 months as an Intern. Most of my time there was spent on a straw-bale residence with passive and active solar and wind elements. By the end of the trip, the significance of this ecologically sound design in the context of the trip would deeply resonate with me.

Several mountain passes later, I was delirious from combining the blushing tones of changing aspens, restless car naps, and The Clash’s weirdest album. We arrived at Mesa Verde just as the sun was casting dusty crimson and purple shadows over the desert landscape, feeling as if I had stepped into an O’Keefe painting. We bought our tickets for Saturday morning and were informed that Weatherhill Mesa would be open for hiking and cycling the following day (it usually closes on Labor Day for the remainder of the year), with Long House and Step House open to self-guided tours.

We began the day at Cliff Palace, the largest and most well-known of the ruins at Mesa Verde. The dry, cool desert air of the morning was invigorating, but once it began to heat up, the cool recesses of the alcove below the cliff helped keep us comfortable. The tour was rather bland, but Cliff Palace does contain some excellent examples of places where the Ancestral Puebloans integrated their constructions with the living rock of the cliffs, as well as several well preserved living structures. The most interesting aspect of Cliff Palace for me was the siting. It is positioned underneath an alcove with access from cliffs in front of and to either side of Cliff Palace. This means when one is on the mesa, they are above Cliff Palace with no way to know they are above a small city - an ingenious defensive position. Cliff Palace seemed to typify the ability of these peoples to collaborate, cooperate, and to work and live as a tight social unit.

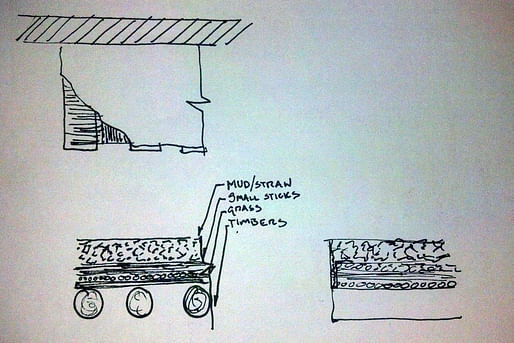

The next space we toured was Balcony House, a smaller compound of living, working, and religious spaces tucked into an alcove two thirds the way up a several hundred foot tall sandstone cliff. If there was one thing Balcony House personified, it is the ability of these people to integrate their architecture with the natural world, to use living stone to enhance their surroundings rather than placing themselves in opposition to it. Hand and footholds scaled a 30 foot sandstone wall, landing at a small ledge. Following the ledge, one passes behind a vertically proportioned space that seems to cantilever off the cliff. After squeezing behind this room, the space opens up to a wide patio, suspended hundreds of feet above the canyon floor. Towards the back of the alcove, rooms stack in neat two high sets, a high stone wall hems in the edge of the cliff. The architecture here is defined by the regularity of apertures and the uniquely preserved balcony which runs between the first and second story of living quarters. The balcony is deteriorating, and pulling away to reveal a cutaway section of the various layers of structure, insulation, and stucco which make up floors and ceilings in Pueblan architecture.

We proceeded to Weatherhill Mesa for some self-guided time in Long House and Step House, taking the opportunity to examine construction details and to sketch. It was interesting for me to check out the steps above the eponymous Step House - they were almost identical in proportion and depth to the many staircases I encountered at Machu Picchu, and various other sites in the Americas. Step House also showed an excellent example of the evolution of Pueblan dwellings, from shallow pits dug in the ground and covered with Pinon timber to small villages, and finally to small villages in the alcoves of the cliffs.

At each of these sites, there is at least one kiva, the Ancestral Puebloan room of worship, at most there are many, even dozens. Archaeologists believe that each kiva was the spiritual center of a family unit - from 10 to 30 people loyal to their mother’s bloodline. Architecturally, the Kiva shows the greatest planning, adaptation, and transformation over time. The Kiva can clearly be trace to the antecedent conditions of the pit houses, where a circular depression in the ground became a gathering place for each family unit. The late kiva retained many vestiges of this time, including the fire ring, the wind block, and the unique system the Puebloans used for delivering fresh air for combustion. As the Puebloan moved to the underside of the cliffs, the kiva became deeper and more entrenched, with longer and more complex air delivery systems, a structural order showing symmetry and symbolism, and even fine finishes appearing inside these religious spaces. To closely examine the many kivas was a unique opportunity as anyone with a finely practiced eye for structure and repetition can move through the sites in the same way the Puebloans proceeded through time, tracing the development and evolution of this particular cultural indicator. Kivas are still used today in the cultures of many peoples who descended from the Ancestral Pueblo people.

On Weatherhill Mesa, and on both mesa tops, it is possible to find evidence of the many reservoirs and aqueducts that the Ancestral Puebloans built on this land. As I have travelled and explored various archaeological sites, I have noticed that the degree to which a culture is willing and able to modify its natural environment is a good indicator of the complexity and scientific understanding of a society. The Ancestral Puebloan peoples had a vast network of aqueducts, reservoirs and cisterns with the ability to store water to bridge decades long droughts. This technical mastery indicates a culture advanced to a point which would typically be called a civilization, and with 20-40,000 inhabitants at the height of its cultural expansion, it was certainly one of the largest and most culturally refined pre-columbian civilizations north of the tropics in The Americas.

While returning to Denver, I started considering the kind of civilization that produces a legacy such as Mesa Verde, and considering what kind of built legacy our culture will leave. Yes, there are the architects concerned with leaving beautiful ruins, and the rare patron willing to finance such ambitious construction, but this will not be our legacy. Our legacy will be the small and inconsequential buildings which survive by chance and circumstance, those which give archaeologists clues into our life, our beliefs, and what we saw as our legacy. The inhabitants of Mesa Verde centered their lives and their architecture around respect for and worship of the earth which predicated strategies for their places of living, worship, and community, and it is in this connection to and symbiosis with the earth which provides for us the most salient lessons for our built environment today.

A blog covering the various processes, methods, and pitfalls involved in designing, producing, and fabricating large scale sculptural and architectural features.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.