M. Arch Thesis - Matthieu Bain + Andrew Perkins

(Part I: http://archinect.com/blog/article/39333739/survivalist-architecture-dwelling-on-waste)

It’s said that “all good architecture leaks,” which makes the home we bought and moved into in October 2011 (for $800) something of a masterpiece.

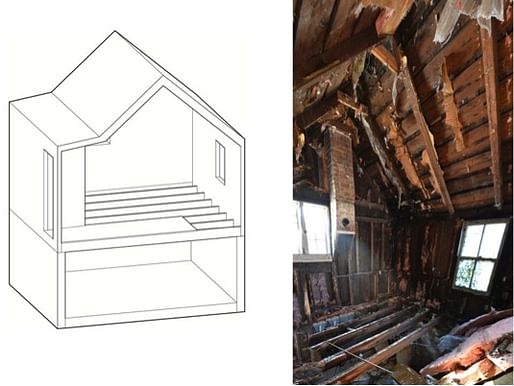

Substantial water damage. Layers of moldy carpet atop layers of rotting wood atop mammoth-sized slugs. We sought a house that was deteriorated far beyond usual standards of comfort: one whose very deficiencies foster creative solutions. From the chaos we separate cotton from plastic, metal from paper, and glass from polyester and vinyl.

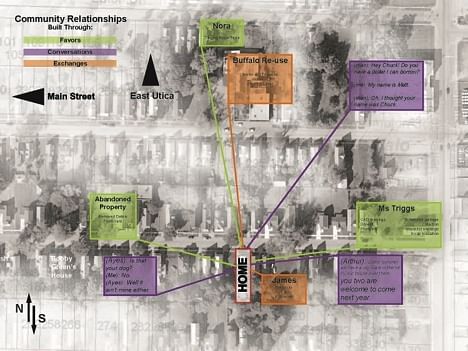

We liberate waste objects – those materials which seem to have no other destiny than decay or landfill. Abandoned houses, curbside trash mounds, vacant lots where storefronts once sat, and construction dumpsters provide an endless supply of building material. From this, we attempt to not only achieve a space that can sustain us, but one which is highly accessible financially, surprisingly beautiful, and has a much healthier relationship with our natural environment.

Immediately, little of the space is inhabitable. We create a shelter within the shelter; suspending a solar pool cover from the ceiling creates a retreat which helps retain body heat while sleeping – a confined space that can sustain us until a heat source is established.

We come upon an old wood-burning stove made from two steel barrels. With temperatures by late October already dipping into the 30’s, we opt to install it as quickly as possible. With the existing brick chimney in shambles, a new chimney set up is needed. Since it is one of the few things that poses serious life safety risks, we observe NYS building code closely. Double insulated chimney pipe is required anywhere the chimney passes through floors or ceilings - otherwise, an 18” clearance from combustibles must be maintained. Insulated pipe is over $100 for a 2’ length, as opposed to $10 for an uninsulated section. The upper floor is cut back to accommodate the given clearance.

The use of more uninsulated pipe saves money, keeps less heat from escaping up the chimney, opens the space which becomes the new center of activity, and ultimately challenges typical responses to building codes. Spaces shift in an acknowledgment of changing environmental challenges and exhibits our ability to overcome or integrate through material interventions. Eating, cooking, sleeping, and leisure spaces are all re-organized around a central heat source.

Basic systems for lighting, water, food storage, and cooking are quickly established and as more materials are brought in, the spaces and systems rapidly evolve. The house can now start to address more culturally rooted human needs: social interaction, tradition, ritual. It becomes the venue for the annual Thanksgiving dinner which has become tradition amongst our friends. The dinner becomes a pivotal point in the life of the house: a resuscitation of space that hadn't seen true life in over twelve years.

Beyond November, the warmth from the stove is quickly sucked out of the walls and windows of the house – all of them uninsulated. Ways of retaining heat become priority and take on several forms: a thermal mass of bricks to surround the wood stove, storage of our fuel supply as an interior partition to condense space and keep the wood warm, window coverings, and scraps of insulation.

Scraps of insulation are pulled from everywhere we can find them – the bulk of it being fiberglass insulation from the back of our own house which is too waterdamaged to be of use. Repurposing this in the attic above the hearth creates a super-insulated pitched space where heat can rise and sit. Even with temperatures approaching 0 degrees, this area can easily reach 70 or 80 – all without paying for fuel.

As the worst of the winter months pass, attention can again be given to places of leisure and relative luxury. Places of cooking, socializing, and lounging.

With the second floor approaching some state of “completion” and the project in general approaching realities of safety and possible code enforcement, fireproofing is added to the roof assembly where it previously wasn’t needed as an unoccupiable space.

With the second floor approaching some state of “completion” and the project in general approaching realities of safety and possible code enforcement, fireproofing is added to the roof assembly where it previously wasn’t needed as an unoccupiable space.

An abandoned house down the street shows signs of the first phases of demolition. Not hindered by the guilt of ruining a house which may still have life ahead of it, we become free to tear into it and liberate as much of its materials as we can: more insulation, drywall, lumber. The drywall, whose screws have been plastered over, rips off into smaller, crude pieces. Their edges are then trimmed and smoothed to fit, creating an ironic aesthetic which seems to mock that of “high design.”  The back of the house, which has largely been ignored as a space – its state of decay and inhabitability initially beyond our means of intervention – can now be addressed.

The back of the house, which has largely been ignored as a space – its state of decay and inhabitability initially beyond our means of intervention – can now be addressed.  The floor has been partly removed by stepping through it – the finish walls removed to be repurposed in the attic – the structure of the room bows out heavily, soggy to the touch. Much of it has to be restructured and rebuilt, which creates the opportunity to open this large south-facing space to daylight and the backyard.

The floor has been partly removed by stepping through it – the finish walls removed to be repurposed in the attic – the structure of the room bows out heavily, soggy to the touch. Much of it has to be restructured and rebuilt, which creates the opportunity to open this large south-facing space to daylight and the backyard.  The floor joists and CMU foundation already near collapse are stripped, and a far more robust foundation installed in its place.

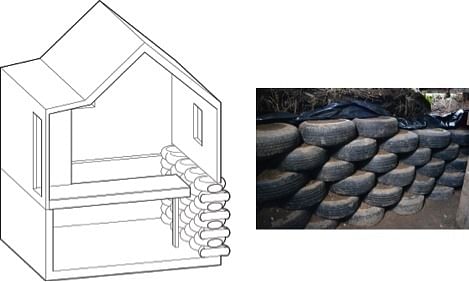

The floor joists and CMU foundation already near collapse are stripped, and a far more robust foundation installed in its place.

The tire foundation requires about 300 pounds of dirt packed into each tire. The tires are a kind of permanent formwork for the dirt and act as oversized masonry units, staggered by course. Opting not to rebuild the rotted floor, a triple-high space results.

The south wall that faces the backyard is also in need of substantial rebuilding. The wall is replaced completely with a glazed system, embracing the space as a seasonal one.

The home is a mutable space – a constant recognition of wavering environmental, economic, and material contexts. The seduction of false progress is only temporary, and we are beginning to approach the threshold of forced reality. Current acceleration in the construction and demolition of neighborhoods, infrastructures, and objects signifies a flux between past and future, altogether avoiding the present.

Since waste is an inevitable byproduct of everything we do, we must overcome it socially and rid it of the taboo it has come to possess…a reevaluation of “value.” Ultimately, this leads to a relationship in which the home is open to a constant flow in material organization as opposed to the standard model of isolation and rejection.

Our work may be seen as a sort of exaggeration – a critique of consumerism and the indifference to waste which has become the norm, of the sterility and preciousness of “high design.” If the responsibility of the architect is to situate material among context, the challenge is not to achieve a trashless space, but more flexible aesthetic and functional criteria to embed it in. Waste isn’t something to be shunned, but an underutilized resource capable of far more than we generally like to admit – not only a driver of ecological systems and financial accessibility, but an instigator of new breeds of architecture.

Check out the blog for more: http://dwellingonwaste2.blogspot.com/

Learn more about the research and creative activities of our enterprising students and faculty. At the School of Architecture and Planning, we engage with our local and global communities to push the boundaries of our disciplines and innovate the professions of architecture and planning.

2 Comments

I am a little concerned that your local building/health inspection department will shut you guys down - but if that does happen, another opportunity to explore consumerism's reach into regulation.

interesting project!

Good point, and a big fear of our own. In such cities of high abandonment (Detroit, Cleveland, and others can relate), there is hardly enough manpower to be able to keep on eye on everything, and we went 8 months without a single problem (or even notice) from the city, despite obvious occupancy.

Despite breaking some health and building codes, we are improving on the property. And our mere presence does undeniable good for the community. Our hope is that any officials would see past these infractions to the more humanitarian side of it all. Many people are financially unable to upkeep their property - especially the many large old homes in the city. We can either maintain current regulations and let homes continue to rot until they're demolished for $20,000 each and replaced with a plastic box, or we can start to encourage a more flexible kind of relationship between code-bearing officials and home owners which fosters healthier outcomes for both sides and the city as a whole.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.