Modelo recently interviewed Aniket Shahane the founder and principal of Brooklyn-based firm Office of Architecture. Shahane splits time between leading his firm and teaching at Yale University’s School of Architecture. Last week, he spoke to Modelo about starting the firm, his approach to teaching and the kinds of projects he aspires to create.

On his start

In college, I went to the University of Texas at Austin, and like a lot of people I just checked off a box and declared a major. I think I was a business major or something. You’re 18 years old, I didn’t know what I wanted to do then. Sometimes I even wonder what I want to do now (laughs). I always had an interest in architecture; I just didn’t realize it was architecture. A friend of mine was actually in the school there, he suggested I take an elective Architecture and Society course. I had the option to switch over to architecture to try it out, and that was it.

I actually struggled through school quite a bit. It’s not like I took my first studio and that was it. I had never drawn before. I didn’t know anything about anything. I struggled all the way through. I had a few teachers who took pity on me and allowed me to pass some classes, which looking back now I should have probably failed. I finished school, started working. I moved to Barcelona for a few years and worked for Enric Miralles there. Then I started dabbling in competitions on my own. Then I got into teaching. I lived in Boston and somehow I fell into teaching at the Wentworth Institute of Technology. I was teaching Second Year Design Studios. I felt like, “Ok I will stick with this.” I think teaching was part of why I continued down the path of being an architect. I really enjoyed it, and ironically it made me realize that I actually wanted to practice.

Tribeca Loft Interior (Photograph by Kishore Varanasi Courtesy of Office of Architecture)

On starting his firm

After Wentworth when I started teaching, people told me if I want to continue teaching I should probably get a Master’s Degree. I went to Yale for graduate school and Yale was the complete opposite from University of Austin for me. I’d been out of school for a while and I had been working for a while too. It felt like a vacation and that I was doing it for myself. At UT I felt like it was a constant struggle and I was failing half my courses. One of my critics at Yale, Joel Sanders, he offered me a job out of school and that took me to New York. That was a really great experience because that’s when I learned how to work in New York which is a very different beast than working in a place like Boston or any other city. So I knew even when I started working for him that I was eventually going to have my own practice and the experience there gave me the push to do that. I started out of the basement of my house, transitioning out of my old office and beginning this new thing. Eventually three years in we became official, I hired my first employee, and we moved into this space. We’re still kicking.

On the relationship between teaching and practicing

I’d like to say the main reason I teach is because I really enjoy it. I love going back to school and I love talking about architecture and being able to talk about it with other students, being part of the community there. Yale just has a really great group of teachers and reviews are always fantastic. It’s purely fun for me. For selfish reasons, I do it because being in that kind of environment really helps you think about why you’re doing what you’re doing. When you talk about architecture, the issues in architecture, what it means, what is the role of architects, why we need them… you discuss those things in student project reviews and you can’t help but question what you’re doing with your own work. The nature of school prods those questions and it’s important to constantly be questioning yourself. Not to the point where it paralyzes you, but enough so you can make sure what you’re doing is worthwhile and meaningful.

Sometimes I teach the M.Arch 1 urban studio, but usually I teach the post-professional studio, I actually co-teach it with Ed Mitchell. It’s a lot of fun for me because Ed Mitchell is the director of that program at Yale. He’s been teaching there for a while. He was one of my teachers. We get along really well. School can be very much about ‘capital T’ theory — the relationship of architecture to its own cultural, historical construct. I come at it from a theoretical perspective but I joke that I’m all about the ‘lowercase-t’ theory. For me, anyone who has a brain and thinks about what they’re doing theorizes. So theory takes the form of the academy which is De Certeau’s “Practice of Everyday Life”. But it’s also present in actual practice; in everyday life. Building code is also a form of theory. Theory is thinking about codifying things in a certain way, how you design, how you write a contract and what you want out of a project as a designer, what you’re going to get out of it in terms of money. That is also a form of theorizing.

Boston City Hall Plaza Chair Formations (Courtesy of Office of Architecture)

On his unique approach

I think practice is about figuring out your approach by doing the work. One of the things that definitely drives the work is an interest in the city as is — there are some people in school who define the real world as the built world. And then there is the speculative theoretical stuff. For me I feel as if there’s a lot of inspiration and speculation that can come from within whatever this real world is. I’m just as fascinated by New York as a city just the way it is with all of its ugly buildings and beautiful buildings as much as I am by those individual one-off pieces. I think that aspect of it, to try to think of every project as something where the sort of practical constraints of the project aren’t just mundane things to get past. That imagination can actually come from the practical constraints themselves. That’s one of the things that drives the office.

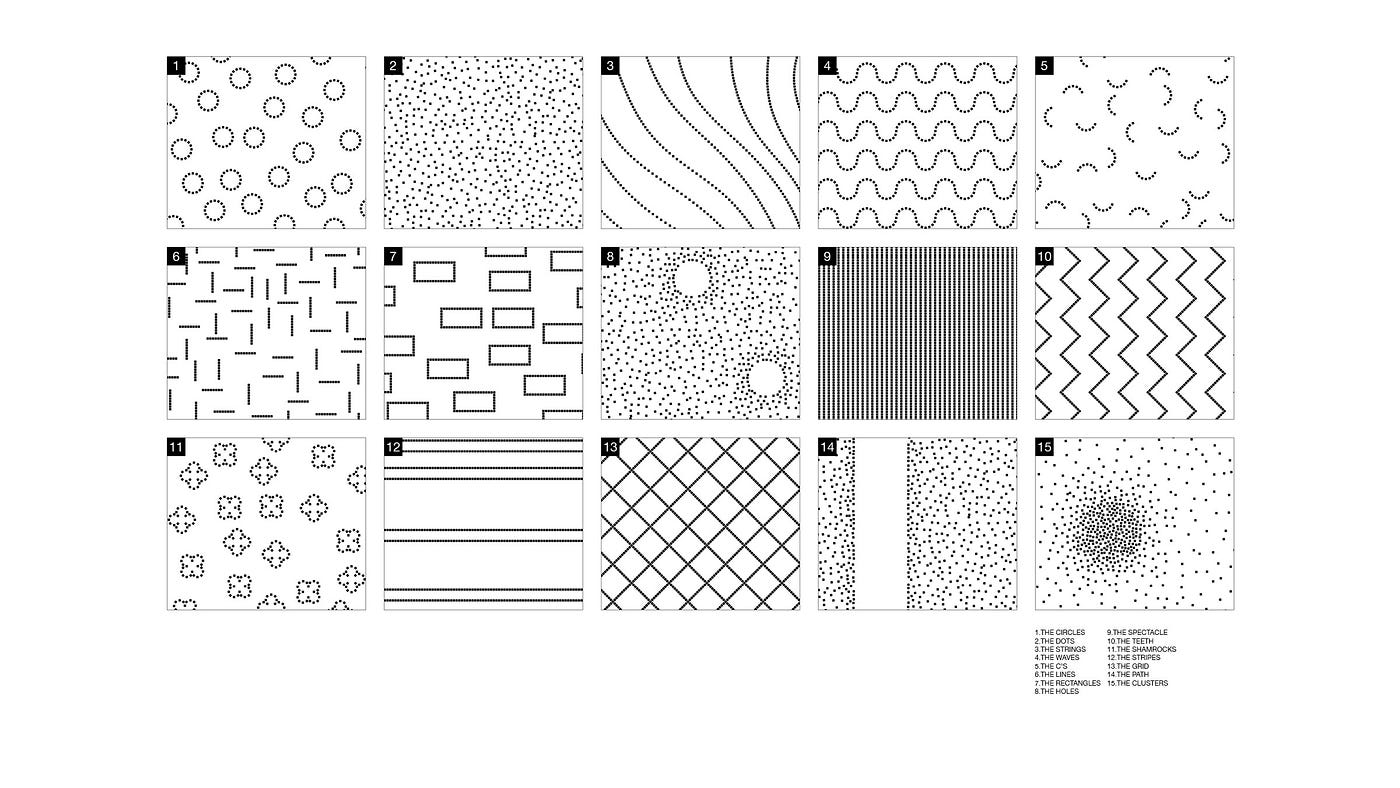

We actually did a project recently for Boston for the city hall plaza. They were looking for ideas for what to do with the plaza. We went there for the informational meeting and we proposed a thousand rocking chairs for the plaza. But rocking chairs arranged in all these different ways. It’s almost like rather than designing a new building, building a new infrastructure, putting in a big pool… we wanted to do something practical in the sense that it’s a chair. You can go and buy it from Home Depot but get a thousand of them so it is elevated from something that’s just practical and becomes much more imaginative. So we proposed that to them and a whole bunch of different patterns that those chairs could be laid out in. In the same way you hire an event planner to lay out your wedding seats you hire an event planner to lay out these chairs in the pattern of shamrocks for St. Patrick’s Day. The thought being that, because they’re chairs, eventually people would use them and move them around and they’d get spread out in different ways. The thought of showing up, coming out of the subway on the green line and seeing the City Hall Plaza, the morning these guys finish setting up those chairs and finding a thousand chairs arranged in the configuration of shamrocks was a really powerful image for us.

Boston City Hall Plaza (Courtesy of Office of Architecture)

I don’t know what that means in terms of a manifesto, but there’s something about that project that has the spirit that drives the office. It’s ultimately imaginative and fantasy. But that fantasy is based in some sort of really mundane reality like a chair. What ended up happening afterwards is we went up and presented the project in person to the woman who was heading the committee and we’ve been in touch with her and about a month after we submitted this thing they put in Adirondack chairs in city hall plaza. Maybe 100 of them. It wasn’t quite the same thing, but it did influence their thinking in some way.

On his dream project

I think something like that, some sort of a public space project. That one. That right there. That would be a dream project. We did another competition over the summer for Portland where they were looking for ideas for what to do for the underside of this highway. We thought, what’s the least we can do here to maximize the effect of what’s underneath? We proposed these large outdoor patio curtains of different levels of opacity. There’s currently a parking lot underneath and we proposed using the parking lot as is now but when the parking lot is empty those curtains can be configured in such a way to create different lighting effects on the inside and it basically ends up being a really open flex space. We did a bunch of different scenarios of how it could be a market, how it could be a disco, how it could be a church. It’s one of those things, and it goes back to why it’s nice to teach, all these projects are ultimately questioning what architecture is. Why do we do what we do and why is it even necessary? That would be a great project to do. That and a city that is the size of a medieval city. A city that’s the size of the block we’re on, but a whole city.

“Church” The Portland Proscenium (Courtesy of Office of Architecture)

On the future of architecture in the next five years

I would think it would have something to do with technology but not in the sense of which advances in technology will cause a productive disruption in the field, but what are the kinds of breakdowns of technology that will cause that disruption? Will we get to a certain point where we think, this is almost too much? Will I want to go back to scribbling with a stone on a slab of marble or something? At what point will certain fields or aspects of architecture return to where the most primitive form of technology will actually be more effective than the most advanced form of technology? That topic comes up here in the office a lot of times, too. For me personally I would be interested in that.

On the future of his firm

I’ve always worked in small offices. We’re currently three people, I would love to grow to five. The projects that we’ve built so far have all been residential and fun and in the end they all end up being projects about the city in some way. I want to do a thousand rocking chair type of project in Boston City Hall. I’m not talking as an installation, I’m talking as a permanent thing. There, part of the mayor’s maintenance committee is this committee that goes out and sets up these chairs in a formation once a month or so. I would love to do those kinds of projects. I think that would be the goal in the next 5–10 years. Do those kinds of public projects and grow the office to five to seven people. We have a joke in the office where we talk about getting to the size of a band. It would be nice to get to the size of the Stones or Radiohead.

Brooklyn Rowhouse Wireframe (Courtesy of Office of Architecture)

On the evolution of his firm

One of the biggest things that has changed since then is that when I first started, I used to do all the drawing work, all the CA work, all the modeling, do everything — now a lot of that is done by the team. I find myself more in the role of guiding the design direction of the projects and also looking for and getting new work, how to get new work, and dealing with the financials. Now we have meetings to talk about a project. We’ll toss out ideas and there’s a certain direction I would like to see a project go and I’m responsible for thinking about how to set up a conversation and a process in the office so we can get there. It’s very different from what it was in 2009 when I was in the basement of my house doing literally everything. That’s been the biggest change and probably one of the nicest changes — the conversations we have in the office. Whether they’re about a church under a highway or about a very practical problem that came up in the field the other day. Why do we have this two foot piece of wall? Why don’t we just have a sliding door that’s two feet wider? To just have that conversation with two people in the office who are really smart and talented is really interesting. I think getting up to five would be nice because I think that energy in the office would be good.

That’s the other thing. There’s kind of a tradition in architecture where you have an office and you’ve got two guys who get paid and 100 interns running around working for free. I’m not interested in that model at all. I’m much more interested in having five people who are really smart, sharp, and talented, and really on the edge of their toes and when a panic call comes in from a client or contractor with some big problem, they can handle themselves articulately. That’s super important. I’m much more interested in having people around who will be like that rather than having a bunch of people running around and they come and go in two or three months.

At Modelo we want to know what drives the world’s design and architecture talent. This is why we invite select architects and designers to share their stories, philosophies, visions and favorite works with the public — their manifestos. For more information on how we're working to change the architecture and design world at Modelo please visit us at: www.modelo.io.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.