The printed catalog for “Air Rights” – an exhibition by the Drone Research Lab (DRL) at the Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning – begins with a Bartlett's-worthy quote from R. Buckminster Fuller: “You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.” It is often observed, on the contrary, that unmanned aerial vehicles, unlike the billion-dollar state-of-the-art fighter jets they are replacing in some military applications, are a cobbling together of existing technologies. None of their components (aside from advanced optical sensing) is inaccessible to everyday consumers, and the mechanics would likely be familiar to Fuller himself.

There is a bit of a misalignment, therefore, between Fuller's technocratic futurism and the often improvised aerial robots at issue here. This contradiction is highlighted in the foreword provided for the catalog by Evan Roth of the Graffiti Research Lab, which emphasizes the process of technological misuse and civil disobedience of taggers and hackers. Misuse and disobedience are certainly a strong ingredient in some of the works in this exhibit, and are in evidence in the activities of the DRL during their first few months as a going concern. The exhibit seems to argue that the site of misbehavior and appropriation is shifting from the tagged surfaces of graffiti to aberrant spatial practices of collection and documentation. As the exhibit's name implies, the space above or adjacent to buildings – a valuable property in some cites – can and should be politically contentious, a space in which to assert one's rights.

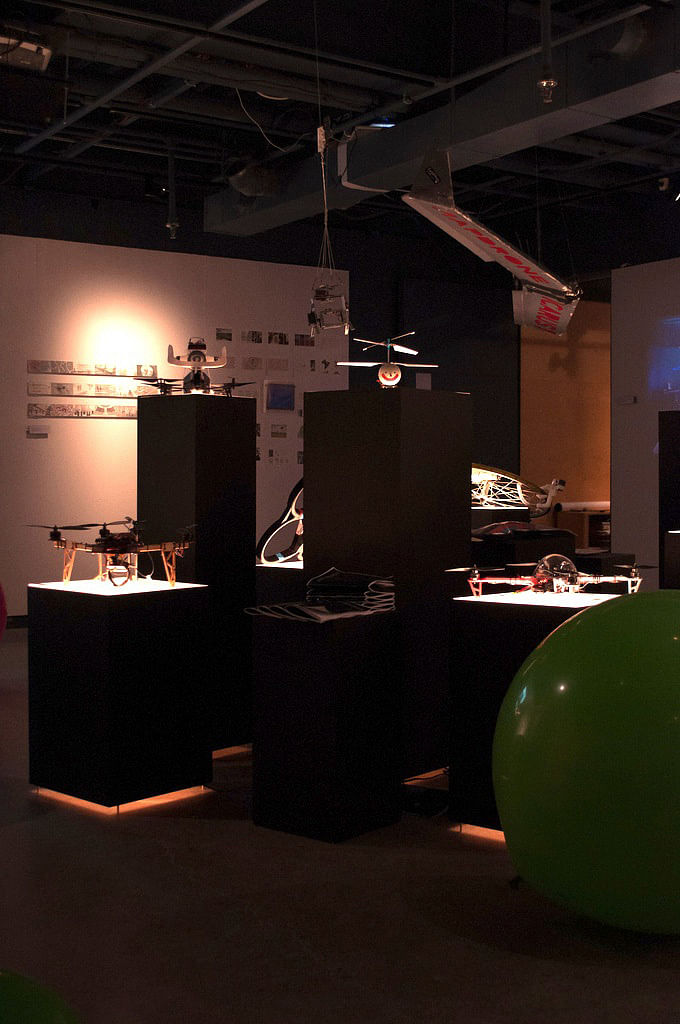

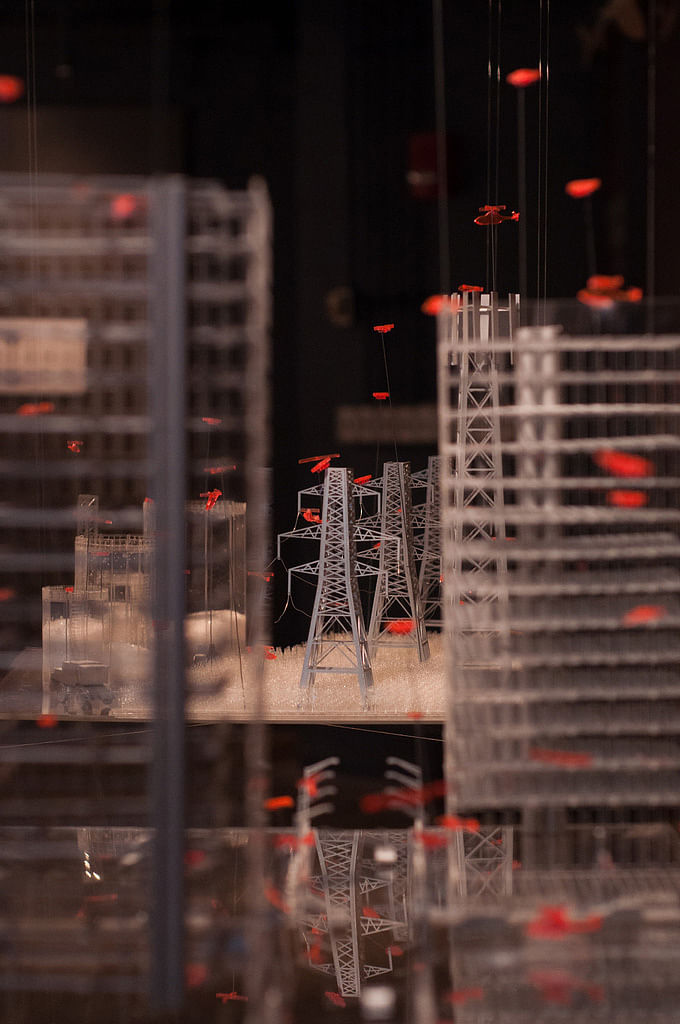

Misuse and disobedience are certainly a strong ingredient in some of the works in this exhibitOperating as a kind of clearing house for ideas regarding drones and urban space, the DRL hopes to provoke more broad questions about the relation between aerial robots and everyday habitable spaces. This first collection of speculations is both critical and productive, but the tension between futurist and bricoleur mentalities persists. The show is a mixed bag, displaying everything from a metaphoric play on US intelligence procedures to a pragmatic consumer drone kit. Notably absent is any attempt at using drones for the fabrication of habitable spaces, an application pioneered by Gramazio & Kohler's “Flight Assembled Architecture” experiment conducted at ETH Zurich in 2011. The products here are largely the machines themselves, which are given pride of place in the center of the gallery.

Among the show's standout works is James Bridle's “Dronestagram,” which adopts a social media format to disseminate data about US drone strikes, accompanied by an aerial photograph of each strike's geographic location. Juxtaposing the human toll of asymmetrical warfare with everyday digital mapping, Bridle's work is a poignant reminder of just how inhuman and indifferent such technology can be.

A similar sentiment is present in Axel Brechensbauer's tongue-in-cheek “Peace Drone,” which proposes to substitute the US Military's destructive firepower with potent pharmaceuticals. In place of guided missiles, Brechensbauer's drone would emit a fog of oxycontin, a highly addictive and euphoria-inducing form of air superiority.

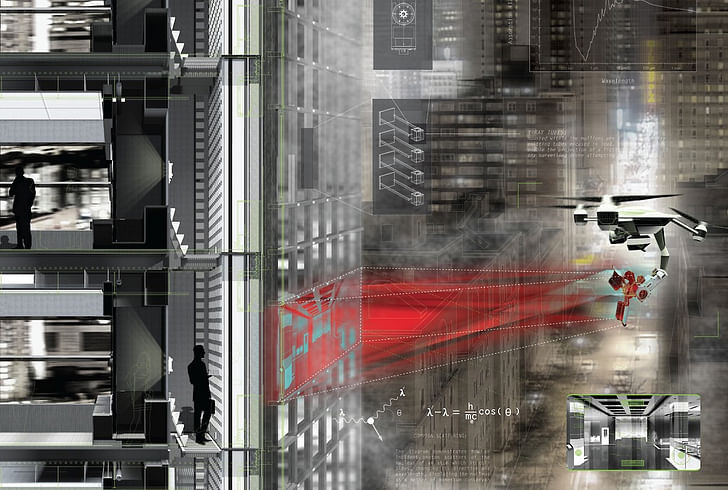

The project with most direct architectural implication is “Metropolitan Membrane” by Casey Carter and Jeff Nader, two Taubman masters students. Their proposal for a building envelope resistant to the ubiquitous aerial surveillance of a dystopian future is one of the show's most speculative works, and among its most elegantly represented. Equally seductive are Mahwish Chishty's “Drones as Folk Art,” in which the surfaces of US Predators and Reapers are embellished in the style of Pakistani trucks.

The most jaw-dropping project is “Charon” by Sterling Crispin, in which the movements of a drone in a motion capture lab are materialized as a linear extrusion through 3D printing. This trace manifests not the instructions of a remote pilot, but an autonomous, hovering vehicle reacting to Crispin's own movements in a peculiar, responsive choreography. The filmed results are extremely striking.

DRL's primary contribution is a drone named Balthazar, after the late architectural photographer Balthazar Korab. Thus far, their drone has been used to provide new perspectives on familiar spaces, an assertion of their own “air rights” and manifestation of a desire for unconventional architectural documentation. Such desires are specific to the academic environment and postindustrial landscape in which the “lab” operates.

The DRL may currently find itself on the front lines of a new revolution in spatial navigation and documentation, but this famous statement by one of Fuller's most fanatical apologists, Reyner Banham, remains as true, and as forbidding as ever:

The architect who proposes to run with technology knows now that he will be in fast company, and that, in order to keep up, he may have to emulate the Futurists and discard his whole cultural load, including the professional garments by which he is recognised as an architect. If, on the other hand, he decides not to do this, he may find that a technological culture has decided to go on without him.1

Drones may soon transform our experience of buildings and cities, and the works in this show provoke reflection on what should and what will happen to architecture in response. If in fact this exhibit (or the unmanned aerial vehicle more generally) poses a new model for architectural thinking that would satisfy Bucky Fuller, it will take thorough unpacking and further experiment to determine just what it is. The question remains: will the relationship between drones and architecture be contentious or harmonious?

Air Rights: an exhibit by Drone Research Lab (John Hilmes and Dillon Erb)

Supported by the Emergent Project Student Research Grant

University of Michigan Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning Gallery

October 2nd – October 17th 2013

Click here to read the digital version of the exhibit catalog.

—

1 – Reyner Banham, Theory and Design in the First Machine Age (London: The Architectural Press, 1960): 329-330.

Michael Abrahamson is a Visiting Assistant Professor at the University of Utah and PhD Candidate in the history and theory of architecture at the University of Michigan. He operates a Tumblr blog called Fuck Yeah Brutalism and frequently writes for The Architectural Review. His writing has also ...

1 Comment

The BLDGBLOG type inquiry walks a fine line between futurism and self-indulgance. How about futurism combined with ethics--to recapture the best part of the modernism dogma.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.