During the yearly art fair in Basel, Switzerland, the city is activated and reconfigured, and art is brought to the forefront of civic discourse. What, if any, impact could the fair have on daily life in a city of 7 million? How would this art world mega-event translate to the Hong Kong context?

When people ask me about life in Basel (my home, briefly, in 2007-2008), I try to answer diplomatically. There are dozens of galleries and museums, a pleasant riverside waterfront, and some excellent cycling paths through the surrounding countryside, but it is a small town, clean and quiet. Basel-Stadt’s 200,000-some residents seem mostly concerned with efficient work, the occasional panache and bocci by the Rhine. Basel really comes alive only a few times per year. At Fasnacht, Basel’s winter carnival, the streets are filled with costumed brass bands and drum corps, and drifts of confetti linger on the typically-spotless streets. Only Art Basel has a similar impact: a temporary reconfiguration and activation of the city.

The yearly art fair - largest in the world by some accounts – attracts over 60,000 artists, gallerists, collectors and other visitors to the small Swiss city, boosting the population by about 30%. The fair has spawned numerous local offshoots, smaller fairs from abroad (like LISTE and SCOPE) have opened Basel editions, and local galleries and museums schedule openings to align with the show. And of course there are the parties – it’s one week when the city can legitimately claim a nightlife. (In Art Basel’s Miami Beach edition, I’ve heard the influence spreads even further, with hundreds of events.)

In short, the fair is a major annual event, its impact spreading far beyond the exhibition halls. During Art Basel, the city is activated and reconfigured, and art is brought to the forefront of civic discourse.

When I heard that Art Basel was planning a fair in Hong Kong this year (or, rather, that parent company MCH had purchased, absorbed, and re-branded Art HK, a yearly event since 2007), I immediately booked tickets from Shanghai, excited to see what, if any, impact the fair could have on daily life in a city of 7 million. How would this art world mega-event translate to Asia?

In most aspects, the fair in Hong Kong is pretty similar to the Basel original. Galleries from around the world set up booths in two gigantic halls in the Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Center (SOM, 1997). In smaller conference rooms, a series of “conversations” took place (all now available online at the Art Basel website. Of particular interest to architects: “Building Asia’s new Museums”).

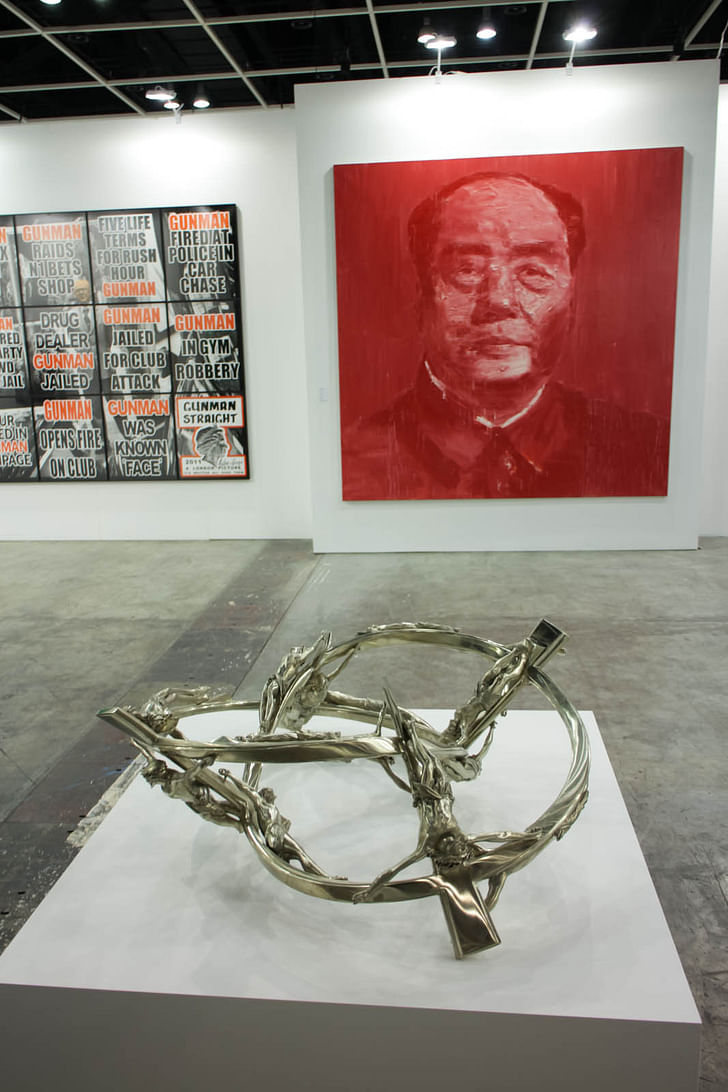

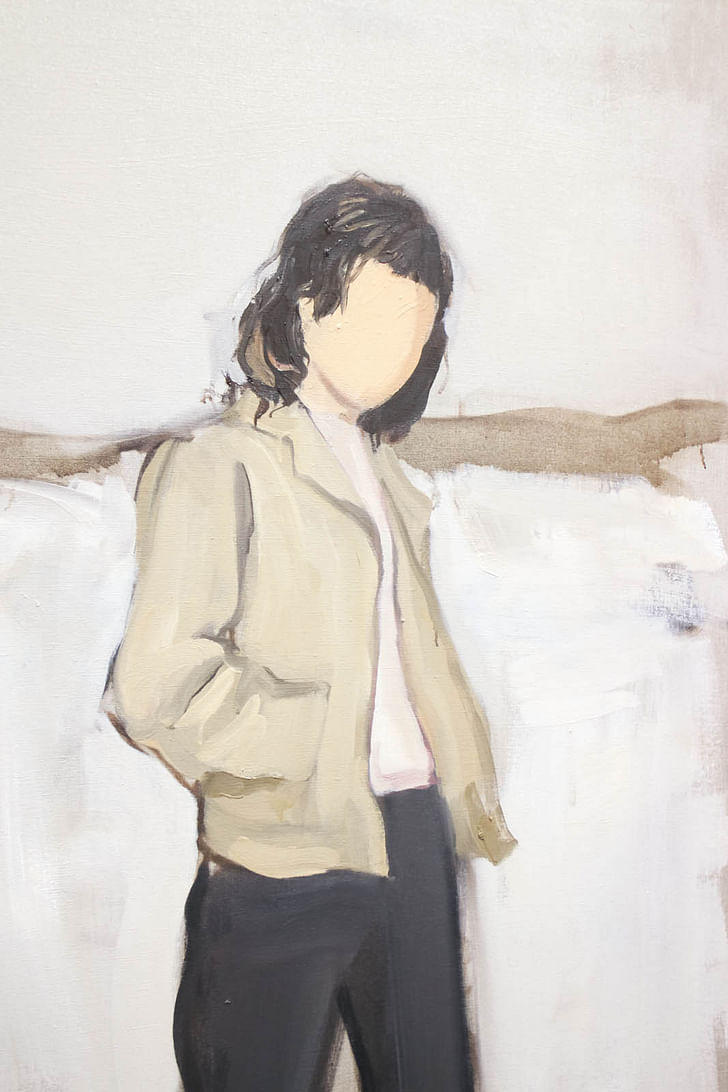

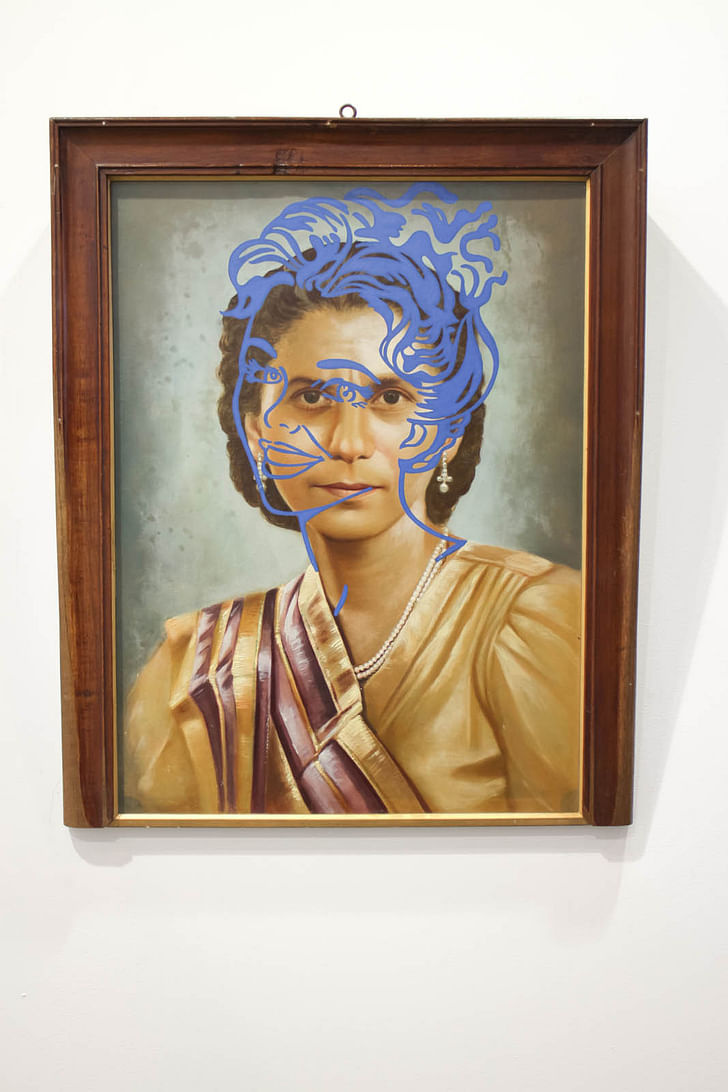

Asian artists and galleries were well represented, as the organizers claimed they would be, with standout pieces from China (artists Yue Minjun, Ai Wei Wei, Cai Guo-Qiang), Japan (Yayoi Kusama; Yoshitomo Nara, Takashi Murakami ), Korea (Do-Ho Suh), and a number of works from Indonesia (where the contemporary art scene is apparently booming). Most Asian countries were represented – if not by galleries, then by artists – as but of course as large a proportion of the work came from the Americas and Europe.

Art Basel is first and foremost a trade fair, and as such there is little thematic consistency, and no sense of a curatorial hand.

While the quality of the work was generally extremely high, and the number of individual pieces almost overwhelming (it took me roughly 6 hours to walk past every gallery systematically), Art Basel is first and foremost a trade fair, and as such there is little thematic consistency, and no sense of a curatorial hand. I imagine each gallery had the freedom to select the pieces to show (and hopefully sell), but as a visitor with no intent to buy, the fair did feel a bit cold and commercial, and a bit incoherent when taken as a whole. The most successful, in terms of presentation, were the “Discoveries” galleries, which exhibited just one or two ‘emerging’ artists, early in their careers. These galleries were a welcome respite.

Outside the exhibition halls, the differences between the Hong Kong and Basel fairs become more evident. Basel’s Messeplatz, adjacent to the exhibition hall, is typically filled with large-scale sculptures and installations, some even visible along the Clarastrasse axis that cuts through northern Basel. Herzog & de Meuron's just-opened Messehalle may block this visual axis, but the square remains a large public space, accessible to all (not just ticket holders). In contrast, the HKCEC juts out on an artificial peninsula in Victoria Harbour, and surrounded on all sides by construction sites. In fact, the only pedestrian access to the building is through the lobby of the adjacent office tower, which connects to Hong Kong island’s vast pedestrian circulation network (and, a few blocks away, to the MTR). The air in the convention hall seems a bit rarefied as a result.

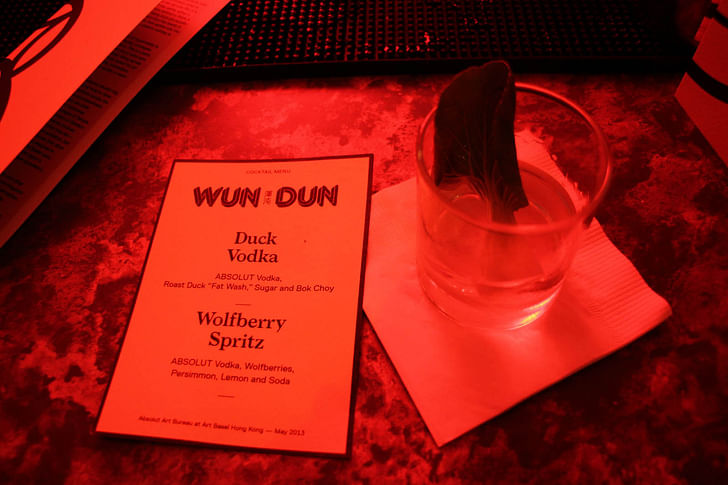

Descending through a speakeasy door to the basement of a French fashion shop, visitors were greeted by an animatronic band fronted by an aging Cantonese lounge singer – bathed in pink-orange light.

As in Basel, the Hong Kong show guide recommended a number of loosely-affiliated exhibitions, gallery openings, and large-scale installations. The Fringe Club's “Wun Dun Art Bar” – designed by Hong Kong artist Adrian Wong was particularly impressive. Descending through a speakeasy door to the basement of a French fashion shop, visitors were greeted by an animatronic band fronted by an aging Cantonese lounge singer – bathed in pink-orange light. The bar served four concoctions (all made with sponsor Absolut’s eponymous vodka), including one infused with duck fat and served with a bok-choy garnish (not recommended).

Across town, the Chai Wan studios held an open studios, as did Fotian and Wong Chuk Hang. These three areas are well known in Hong Kong arts circles for their post-industrial vibe and (relatively) cheap rents – the galleries and studios still share buildings with auto shops and fish markets: a rough and welcome contrast to the pristine and proper show at the exhibition center. It’s reassuring to know there’s studio space available in Hong Kong, and shocking to realize it’s only a 20 minute drive from Central.

A number of galleries across town hung special exhibits to coincide with the Hong Kong show – just as they did in Basel. The Para-Site art space had a particularly good show, whose curator equated the SARS epidemic of 2003 with prejudice and racism, contrasting recent art from Hong Kong with historical documents produced by the British in the colonial era. (The subtext? An indictment of local Hong Kongese and their xenophobic attitude towards Mainland Chinese…)

The Asia Society (in a fine building by Tod Williams & Billie Tsien) hosted an exhibit of underground Chinese art from the final years of the Cultural Revolution and immediately after (Light Before Dawn: Unofficial Chinese Art 1974-1985). This was a small show, but excellent, arranged around three groups of artists who fought – stylistically - against the prevailing state-mandated social realism. The exhibit was organized chronologically, and progressed from pastoral landscape paintings (the Caocao/Grass Society group) to a series of ink-wash paintings that verged on abstract expressionism (Wuming/No Name) to a more eclectic mix anchored by Ai Wei Wei’s surrealist work from 1980s New York (Xingxing/Star group).

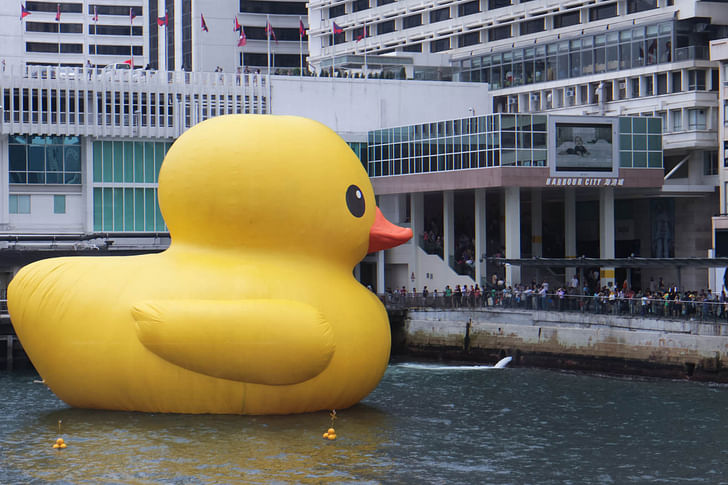

The overscale bath toy essentially turns Victoria Harbour into a tub, and Hong Kong’s citizens into awed kids.

And of course, these days it’s impossible to talk art in Hong Kong, without mentioning the duck. Florentijn Hofman’s Rubber Duck has captured the imagination of Hong Kong’s residents – even as far as Shanghai, local newspapers and blogs report on every new development – ecstatic when it arrived, excited when it’s moved, defeated when it’s deflated, and thrilled when it pops back to life. Sponsored by the Harbour City mall, and now conveniently docked at the Kowloon Star Ferry pier, where said mall’s restaurants can offer “duck view” tables. The overscale bath toy essentially turns Victoria Harbour into a tub, and Hong Kong’s citizens into awed kids. The yellow contrasts with the blue and gray of Hong Kong’s skyline – and the occasional movement, disappearance and reappearance (coupled with Harbour City’s engagement with social media) turns the waterfront into the grounds for a city-scale game of hide-n-seek. (People don’t seem quite as excited by the giant inflatable excrement at M+ museum's Inflatables exhibit in West Kowloon).

While it’s easy to dismiss the duck as a cheap crowd-pleasing novelty, I sense that there are deeper themes. Nearby its current location by the pier, vendors sold bags of the (normal size) plastic bath toys.

This cheap junk is no longer manufactured in Hong Kong, which has successfully transitioned its economy to finance and services – and now serves as a reminder of the not too distant past, when Hong Kong could never dream of hosting an event as prestigious as the world’s largest - and best – art fair.

Art Basel Hong Kong ran from May 15-18, 2013. Art Basel, featuring many of the same galleries, will be held soon, from June 13-16, in Basel, Switzerland. All art from both shows can be viewed in Art Basel's online gallery.

Evan Chakroff is an architect and critic based in Seattle. With a background in engineering and over 10 years’ experience in world-renowned architecture firms in the US and abroad, Evan brings a multi-disciplinary, international perspective to his work. Evan’s architectural criticism ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.