Artist, critic, poet, writer, and Web provocateur Kenneth Goldsmith is one of those rare individuals who create their own gravity. The breadth of interests and activities that have characterized his twenty-three year career alone is enough to command respect, but perhaps chief among Goldsmith's accomplishments is the creation of the online avant-garde archive UbuWeb . Founded in 1996 as a sort of experimental destination and laboratory for various forms of poetry, UbuWeb has blossomed into a premiere educational resource and essential location for all forms related to the avant-garde. The most striking component of UbuWeb as an online institution is that it seeks to create an environment based on the Web's inherent utopian ideal: the free and unfettered access to information. I sat down with Kenneth Goldsmith over breakfast to talk about his transition from artist to poet, the utopian politics of art and poetry,and the foundations, direction, and gravity of UbuWeb.

(0:42) jourden >>> You were born in Freeport, New York in 1961. Can you describe your earliest contacts with art, poetry, and media which may have influenced you and what you do today?

(0:54) goldsmith >>> I had absolutely no contact with art or media or poetry--I grew up in a suburban wasteland of Long Island--all I knew was the television. I grew up in a house that was bereft of culture entirely, but I did have a grandfather who had a fabulous book collection. He collected rare editions of books, so I was intrigued by his collection early on. And that might have been the little portal to which everything grew out of much later. But as far as home life there was nothing...

Listen to the response above. Get the Flash Player to see this player. var archinect_mediaplayer = new SWFObject("mp3player.swf", "line", "436", "20", "7"); archinect_mediaplayer.addVariable("file","no_contact_ubu_054.mp3"); archinect_mediaplayer.addVariable("repeat","false"); archinect_mediaplayer.addVariable("showdigits","true"); archinect_mediaplayer.addVariable("showdownload","false"); archinect_mediaplayer.write("player");

(1:43) jourden >>> Okay, so from there you went on to complete your BFA at RISD . You majored in sculpture then moved to New York...

(02:06) goldsmith >>> I got out of school in '84 and moved back to New York in '85. From '85 till '95 I was an artist in the art world with a rather good career as an artist. You know selling, showing, very good reputation, but what began to happen was, I began working with language and the language become far more interesting then the fabricating of certain objects. I would engage the language then it would take a month or two months to construct that thing. Meanwhile this other language was running through my head, so through a very long process which took a very long time, I ultimately left the art world to write poems. And clearly I was not trained as a writer or anything, but the language just took over, so I ended up writing books. I published my first book in '92, and then really my first book of literature in '97.

(3:22) jourden >>> The first one was a book of poetry?

(3:25) goldsmith >>> The very first book was a book of almost concrete poetry, and this is very interesting because this is where UbuWeb really begins. There is a couple in Florida that run something called the Ruth and Marvin Sackner Archive for Concrete and Visual Poetry based in Miami Beach. They began collecting Russian Constructivists . And when that market heated up and got too hot, they kind of followed the leads of typography from the Russian avant-garde into mid-century moves that were made in concrete poetry and visual poetry . They began collecting this stuff, really at a time when nobody was interested. And they amassed this enormous collection of perhaps fifty thousand pieces of concrete poetry, visual poetry, sound poetry , and text-based works.

As an artist who worked in language, they had bought a piece of mine and invited me down to install it in Miami. This is 1989. I had known about text art in the art world alla Lawrence Wiener , Jenny Holzer , this type of thing, but I had no idea there was this whole other world of poetry that was being used in a visual way. It was called concrete poetry and I knew nothing about it. So going down to meet them in Miami was an absolute eye-opener for me. I was astonished, there was a whole world of visual word-based work I had never known before, and I subsequently became hooked on it. I began trolling used bookstores in New York for little books of concrete poetry of which there were just dozens and dozens. Nobody was interested in this stuff at the time, so I just began making a collection of this stuff through local bookstores, and this in turn leads to UbuWeb . That might be another question.

front page of UbuWeb

(5:38) jourden >>> Yeah definitely. Before we get to Ubu can you talk about--can we just kinda of brief describe what concrete poetry is? Because for me I always think of like--is E.E. Cummings sort of a precursor of that?

(5:58) goldsmith >>> Yeah, very much so. E. E. Cummings you know uses the page, the blank page, the white spaces as a physical space. He doesn't take the page for granted. Most times when we are working on a word processor or writing an email we don't think about the space of the page or of the way the letters sit in it. We don't treat it visually. Now this goes back to the tradition of concrete poetry. Visual poetry goes back to the Middle Ages--there are pattern poems, and a long history of liturgical works. Puritan works that create imageries of fire, imageries of dragons, of architecture all made out of words. This is quite a rich and long tradition that really goes back to the Middle Ages--illuminated manuscripts often create visual structures based on words. However, this really dies out and with advent of standardization of print with Guttenberg, we move into verse, paragraph, sonnet, and columnar, because [visual structures] become hard to type set, forget about making visual stuff on masse. So you get a standardization of type, as you very well know. So the first person that uses the space is (Stéphane) Mallarmé with his Coup de dés , and then of course (Guillaume) Apollinaire follows after that with his Calligrammes . And by the time you hit the year 1913 with various futurist movements around the global, it seems like everybody is exploring innovative uses of typography. Many of whom are simply calling that poetry. It really picks up as a movement, as an international movement after the war in the early 50s with a Swiss poet named Eugen Gomringer . He has an advertising background and is a straight poet. And he sees advertising, the way that advertising is using letters and language in a very unique way--using typography, and begins to have the idea that he can apply it to poetry. At the same time, in Brazil, there is a small group of poets called the Noigandres group, and they are inspired by (Ezra) Pound , (James) Joyce , and (Gertrude) Stein , and they begin working visually as well. So it becomes this kind of worldwide movement of poetry.

Listen to the response above. Get the Flash Player to see this player. var archinect_mediaplayer = new SWFObject("mp3player.swf", "line", "436", "20", "7"); archinect_mediaplayer.addVariable("file","ee_cummings_ubu_558_new.mp3"); archinect_mediaplayer.addVariable("repeat","false"); archinect_mediaplayer.addVariable("showdigits","true"); archinect_mediaplayer.addVariable("showdownload","false"); archinect_mediaplayer.write("player"); Calligrammes: Poems of War and Peace 1913-1916 by Guillaume Apollinaire

Calligrammes: Poems of War and Peace 1913-1916 by Guillaume Apollinaire

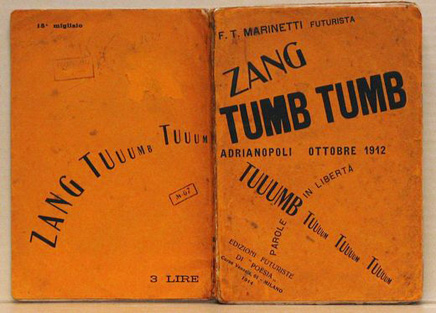

The idea behind concrete poetry (and it's a very interesting idea) is that it emerges around the time of tendencies toward world languages--Esperanto say. And there is a utopian idea of concrete poetry, that says, imagine a poetry that transcends language, that is a visual poetry that can be understood with maybe a key of just one or two words, that can be understood by anybody anywhere around the world. Hence creating a truly global poetry movement and that is the kind of utopian--mid-century utopian idea behind concrete poetry. And it did in fact, people were able to write very simply and very visually using very few words. Say in Japanese, there would be like at the bottom of a Japanese concrete poem a little key , if they're using two words , like the word for rain and the word for snow, and it would be patterns of rain and snow and this type of thing. The corollary of all of that is sound poetry which has a similar idea, and this is a poem that is not meant to be read, but a poem that is meant to be spoken. And that goes back to (F.T.) Marinetti and the futurists--Zang Tumb , (Kurt) Schwitters --but again after the war the technology becomes very important because the tape recorder comes into play, so that language can be bent and manipulated like Musique concrète . Really it's a rich history.

Zang Tumb Tumb: Adrianopoli Ottobre 1912: Parole in Libertï¿ by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti

(11:06) jourden >>> Do you see hip-hop music or spoken word as sort of being part of that, at least the sound poetry portion of that tradition, does it play in that or is it just a completely separate phenomena?

(11:16) goldsmith >>> I think it's a completely separate phenomenon. I think it has some parallels but it's unconscious, extremely unconscious--I'm not sure that much hip-hop is too aware of the history of sound poetry . And I think it does very different things. Hip-hop uses language transparently, in other words it's about semantic sounds--there is a message delivered, a meaning delivered, and very rarely is there not. Where as sound poetry avoids a kind of specific meaning it's much more like a piece of classical music. I think you can make parallels, and you can find in dance music and hip-hop music a lot of sound poetry samples. These guys have plundered some of that and Ubu is actually used as a lot of source material for dance mixes around the world. Very interesting when that happens--I love that!

(12:39) jourden >>> Can you talk about your Uncreativity as Creative Practice and the role of that in your work? It sounds like this maybe even matriculates into the way Ubu functions.

(13:03) goldsmith >>> In my own work--It's little bit complicated--Brion Gysin in 1959, claimed that poetry was fifty years behind painting, and I think that is still somewhat true today. A lot of strategies that have been tested and proven to be good strategies in the art world haven't even been tested in literary circles. I'm thinking specifically in terms of my own work--in terms of appropriation which the art world dealt with twenty-five years ago, and claimed it finally to be a legitimate practice. The literary world is still stuck, very much on conventional ideas of creativity--the mainstream literary movements are all still as if modernism really sort of hadn't happened. You know they're very conventional in expressing ones innermost thoughts in a very sort of discursive way, and there is some free verse, which might be mid-century modernism and some disjunctive stuff. But in fact, really what has became known as post-modern strategies in painting and the visual arts have not even been tested in poetry.

So basically uncreative writing is a way of going against the tendency toward MFA creative writing programs, which don't really teach you how to be creative at all. They're truly uncreative. They're teaching you how to yet write another short story of the rise of a hero and his even more dramatic downfall. Or a poem that is work shopped to death and that is written by committee. To me if that is creativity then I don't want to be creative. Rather I want to be more warholian, I want to be mimetic, I want to be machine-like, I want to take text that have already been written and simply rewrite them and transcribe them without changing anything--claim them as my own simply by the act of retyping say a day's copy of the New York Times. So that becomes my own and simply republishing it as that.

Creativity is such a bankrupt concept in our culture and such an over used cliché, and yet something held so highly esteemed, still, that in order to truly be creative and truly find a way out of that we need to employ a strategy of opposites--we need to be uncreative, we need to be boring , we need to be everything that the culture claims creativity isn't. I teach a class called Uncreative Writing at University of Pennsylvania , in which the students are encouraged to steal, plagiarize, appropriate, file share, falsify--you know things they normally do anyway and they're very good at. And I say, "Well what happens when we take this out into the open, and we use these as legitimate writing strategies. You're allowed to do this--now what do you do with it and what decisions do you make." It's an amazing thing because they're so adept at these skills, and yet they've had to use them surreptitiously--so what happens when we bring this out. Hip-hop for example, nobody expects anyone to get up there and make an incredible guitar riff! You take that from there and take this from there you put it together, and you borrow lyrics from somebody else and put whole thing together. And nobody expects anybody to be original. When Briteny Spears does a concert nobody expects her to sing. And yet somehow in literature we expect, we demand the authentic voice in literature. The whole world seems to be moving in ways of uncreativity yet somehow in literature we're still really, really hung up on old fashion, I think dead notions of what creativity is.

Listen to the response above. Get the Flash Player to see this player. var archinect_mediaplayer = new SWFObject("mp3player.swf", "line", "436", "20", "7"); archinect_mediaplayer.addVariable("file","creativity_ubu_1303.mp3"); archinect_mediaplayer.addVariable("repeat","false"); archinect_mediaplayer.addVariable("showdigits","true"); archinect_mediaplayer.addVariable("showdownload","false"); archinect_mediaplayer.write("player");

(17:52) jourden >>> So in Harpers magazine in February there were a couple of different pieces about plagiarism and appropriation in both art and literature--are you familiar with them? Yeah, okay. So today there is a vigorous argument surrounding the issue of intellectual property, and the line between appropriation and for what the creative act is. Which I think you were eluding to. Your positions seem to have a rigorous insight to these confluences--in terms of these two Harpers articles how do you see intellectual property today together with Ubu and the class you teach?

The ecstasy of influence: A plagiarism by Jonathan Lethem

(18:48) goldsmith >>> The Lethem piece was very good. It was absolutely right on--I really, really loved that. A very, very good piece, and he spells out a lot of that, however, here's the difference. Lethem and Hollywood are playing with things where there are really great finances at stake, and these are very important issues for people that have great money at stake with what they do. You have to figure these things out. We're privileged enough there is no money at stake with what we do. The avant-garde and particularly the ephemerid of the avant-garde has never made money and never will make money! And so, we're a little bit off the hook. We can play it a little bit looser, we can be a lot more utopian about what we do--in what we preach and what we practice, because there is nothing to lose. As a matter of fact, what happens on Ubu most of the time is that people are very happy to find their work there. Much of UbuWeb is permissioned and much of it is not, and very rarely do people seem to care that it's there, as a matter of fact most of the time they are happy.

Let me give you an example, last week we launched--we do an occasional series of electronic books called slash Ubu Editions --full length books, things that are out of print, things that are a little obscure. We never ask for permission we figure if it's out-of-print its fair game. This is really the overriding policy on Ubu, we will not put up things that are in print because we do not wish to take money out of the pockets, however little money it would be, of the people that are actually putting the stuff out and trying to get it into the world. So nothing on Ubu that is up there without permission that's in print. There are a lot of things that are in print that are up there with permission. Where people say to us, "please put it up, it is only going to help our sales!" This last series of Ubu Editions we launched an old book by Robert Wilson --really great--it was a handmade, hand-drawn book from the 70s--for an early opera of his called A Letter For Queen Victoria . It's like 1974. I had a copy from when I was collecting, and it was decided to be included into the series. I get a note about a day later from the Robert Wilson Foundation saying, "We saw that you had this up there. We are very pleased to see you have this up there, however, did you ask Mr. Wilson's permission before putting this up?" And I wrote back stating that we assume that since this book has been out of print for thirty-five years that it really wasn't doing anybody any harm if in fact we would put it back into print. UbuWeb doesn't sell anything. We have a strict policy against selling anything, so therefore we're not making any money on it. And it's simply a site for people who are devoted to obscure artifacts of the avant-garde. I mean this is very, very marginal stuff. In fact it's studied, most of the site is mostly used by educational, K-12 up through the graduate level--very heavily used for mostly educational. And the guy wrote back saying "that we are big fans of UbuWeb, we are pleased to see it up there, and we give you permission to have that book up there. It would've been nice had you asked Robert Wilson." To which I didn't respond but I would say if we had to ask UbuWeb simply wouldn't exist. We act first and if somebody doesn't like the fact that it is up there, we take it down, no questions asked. It's not our property, however, our motives are extremely pure, we're not in this for anything other then to get good works back into circulation. And should they ever return to circulation then we take them off the site. And that has happened several times, where things have gone back into print.

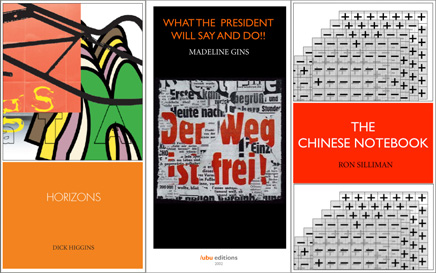

a selection of slash UbuWeb editions

(24:06) jourden >>> Wow, but then again you have a hall of shame ...[laughs]

(24:10) goldsmith >>> Well we're not just going to let it pass. That is actually really recent. The filmmakers have had a lot of trouble with Ubu. They really kicked and screamed finding their stuff up on UbuWeb, but of course it's impossible to see their works any other way. And through our networks we have a plentitude of avant-garde films that have been digitized. Many of them just taken from television from Europe--fans, fan stuff, I mean this is all fan driven stuff. They went kicking and screaming, but once we began to offer the works as streaming as opposed to simply downloadable, they calmed down and began to see the benefit of making the works available. There is nothing that will replace sitting in a dark theater on a huge 35mm screen with a group of warm like-minded bodies enjoying a beautiful film. But unfortunately most of us don't live anywhere near the place--the three places in the world where those things happen to be shown regularly. So this is not meant to be the real thing because it's not the real thing--it's a snapshot--it's a poor substitution. And we like the idea that the film quality is bad because it's going to make you want to go out and see the thing for real. In the hall of shame, no, we're not going to let it pass. If people are being silly and if they insist then we'll call them on that. But the hall of shame is very small compared to the thousands of artists that are up on UbuWeb. It's tiny. So it's working! It's very specific. This wouldn't work for fiction that sells. This wouldn't work for music that sells. This wouldn't work for films that sell--absolutely not it's a very different economy. It's very important to know that our situation is very unique, so we can take liberties that other people don't take and people are with it. It's very, very interesting to figure that one out.

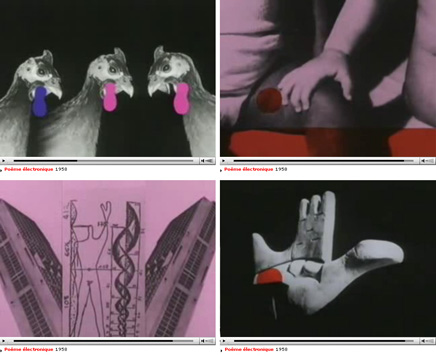

found on UbuWeb films: Poême électronique 1958, by Edgard Varêse and Le Corbusier

(26:44) jourden >>> In 1966, Dick Higgins wrote a short treatise 'Statement on Intermedia '. Do you see UbuWeb as a facet of this position that was calling to develop new "organizations, criteria, sources of information" in light of our new ways of communicating?

(27:12) goldsmith >>> Dick, you know is a patron saint of UbuWeb, and his Something Else Press . Dick was born into a very wealthy family and basically blew his entire inheritance on Something Else Press making beautiful books as he called them--wolves in sheep's clothing that were purchased by libraries all around that had no idea of the explosive content that was inside these things. It's historically one of the most important American presses. Yes, Ubu is an intermediary space in a Higgins sort of way--it knows no bounds. We can't distinguish between film, performance, e-books, outsider art, mp3s, and it's very, very rich, there are all sorts of things on there. And the only thing that pulls the whole things together is a very, very loose and purposely-vague definition of what happens to be avant-garde. I'm not even sure what that means, and it sort of keeps changing, so that the site can encompass from [Kurt] Schwitters and high-art to Louis Farrakhan singing Calypso on the 365 Days Project --you know, some of the outsider stuff that goes on there. To me it doesn't matter. In the 365 Days Project is an mp3 by Nicholas Slonimsky , who was so avant-garde as a conductor he got himself drummed-out of the conducting business. One of the greats, who gave some of the first premieres for Varèse and Ives , and yet here he is in this sort of kitsch collection for no other reason then that these categories are just collapsing. It's a collapsible space and it's very beautiful when you begin to make connections between the outside and the inside, the high and the low, and everything just smashes together. And it's all held together by a very purposely-vague notion of what the avant-garde is, but I think it gives it a clear sense of a vision. I think. You know we're not going to be didactic about it, and yet something--some sort of stew emerges from it that I think is a clear vision of what the avant-garde might be today.

(29:59) jourden >>> It's funny that you mention the avant-garde because it totally conjures--you sing all these... [laughs]... texts ! [laughs] The really funny one in context to what you just said is the Rosalind Krauss piece about the avant-garde. So what are those actually about--are they just fun, witty, or what?

(30:34) goldsmith >>> For many years I've been doing a radio show in New York, a wonderful little free-form station called WFMU . Very well known station...

(30:45) jourden >>> It's the best radio station in New York...

(30:46) goldsmith >>> ...best radio station perhaps in the country! They let you do anything there. And I had been doing a show for twelve years and was getting rather bored with all the freedom that I had for all those years. And so I began singing on my shows. I first began doing karaoke, and I just sing for three hours on mic. Of course as you hear I have a lousy voice...

Kenneth Goldsmith

(31:14) jourden >>> It's not that bad [laughs]

(31:19) goldsmith >>> Believe me for three hours you wouldn't want to listen to it. [laughs] So at some point that morphed--oh I know, the last kind of karaoke thing I did I found the whole set of Tommy by The Who as karaoke dot-KR files, and I spent an entire hour and half singing Tommy from beginning to end. [laughs] And then I began reciting texts--Lao Tzu texts, the Art of War, I read the entire thing--the background to Carmine--sort of sang it for three hours. And that kind of then morphed into theory because it's so absolutely impenetrable--I don't know, I'm not sure if there is a whole lot to say about it other then I've spent an enormous amount of time on the air singing theory. And now people tell me that they enjoy--they actually teach those pieces when they're going to teach Fredric Jameson. They'll actually play me singing it, they say it's great because suddenly the students are actually listening to (me sing) Barthes or Jameson for the first time.

(32:56) jourden >>> When did you first start to create the idea that lead to UbuWeb? How did you first get it started?

(33:15) goldsmith >>> Concrete poetry was modernist in a Greenbergian sense. It embraced all of (Clement) Greenberg 's ideas. The flatness of the picture plane. There was never an illusionistic space in concrete poetries. Hardcore modernist! And it's extremely graphic. The first time I saw Netscape in January of '95, the first thing that really caught me was the interlaced gifs. And I don't know if you remember that. But at the time on a very slow modem you could actually watch them interlace come in and fill themselves in. And that is a very similar tactic to what was used in concrete poetry. Concrete poetry often employed the sequential ideas of the flipbook, so that over a succession of pages, like a flipbook you'd actually see a poem grow. This sort of primitive animation that a flipbook gives you was suddenly becoming very visible on the Web. What I was seeing animation of a gif, but of course the next step was making a gif animated in a series of frames, and with that I thought this is really exactly what concrete poetry was like.

So I took some of my old concrete poetry books (when of course the Web was visual, this was '96) and I just scanned a couple of things, cleaned them up, and put them up--and backlit on a flat screen it was as if concrete poetry had found its medium that it had really been searching for. And particularly with the idea of animation, I thought my god this is what concrete poetry had been waiting for, for fifty years is this medium. So that is the real genesis of [UbuWeb]--putting up a few scans. Then when real audio came in I ripped a few sound poetry files, and began putting up those--on and on. As broadband got bigger and media got richer we've tried to keep at pace with that. To the point when I saw YouTube , I thought this is it man, this is the future, streaming flash files are the future, we've got to move the avant-garde films (of which we have about five-hundred of now) into this format, because this is where it's at now.

I worked in the dot-com business, it was my job for many years, I know how to program, I know how to design, so to actually make the whole thing happen is and remains second nature to me even though I'm not in that business anymore.

Listen to the response above. Get the Flash Player to see this player. var archinect_mediaplayer = new SWFObject("mp3player.swf", "line", "436", "20", "7"); archinect_mediaplayer.addVariable("file","this_is_where_its_at_ubu_3315.mp3"); archinect_mediaplayer.addVariable("repeat","false"); archinect_mediaplayer.addVariable("showdigits","true"); archinect_mediaplayer.addVariable("showdownload","false"); archinect_mediaplayer.write("player");

(36:25) jourden >>> Was that a supplement to you being an artist?

(36:29) goldsmith >>> Yeah. I was making the transition from making sculptures into being a poet. Transitioning from having a good living as an artist to making no living as a poet. So I worked in dot-com from 1993 to maybe 2002, so almost ten years in that industry. So this is all very second nature to me.

(37:03) jourden >>> The name UbuWeb where does it come from, and what is it have to do with Alfred Jarry ?

(37:18) goldsmith >>> Yeah, it came from Jarry . When I was an art student I had a little business to support myself in school doing mold-making and things like that, and I called it Ubu. I think it was Ubu Industries or something like that. I loved Jarry as an art student. I subsequently moved, that is, what I did prior to dot-com in New York, I was a fabricator, so Ubu became the name of the fabrication business I had in New York! And when I got out of that and kind of got into dot-com, I was waiting around--it's a very, very funny story.

woodcut prints by Alfred Jarry for Ubu Roi

Ubu.com wasn't available then, and ubu web was the only thing I could get, so I called it UbuWeb. Later, a friend of mine who I worked with in the dot-com years, she said, "I got a friend and he owns Ubu.com, he's been cyber-squatting, he bought a bunch of these." A guy named Carl Steadman who started Suck Magazine years ago. He had been squatting on it and my friend Vivian was dating him. I said, "Well Vivian you've got to get him to give me the name!" And so she did. I think he sold it to me for a hundred bucks, and I promised him as a result of that, I would always keep it for art and poetry and keep it free. And over the years many people have tried and offered me enormous sums of money to purchase that for their site--you know three letter symmetrical domain name, 'U-B-U dot com.' I can't tell how many offers I've had, but I always promised that I'd keep it for poetry. It's wonderful to reject offers of several thousands of dollars for that name, and say, "I'm sorry but this name will always be dedicated to poetry." [laughs]

Listen to the response above. Get the Flash Player to see this player. var archinect_mediaplayer = new SWFObject("mp3player.swf", "line", "436", "20", "7"); archinect_mediaplayer.addVariable("file","ubu.com_wasnt_ubu_3718.mp3"); archinect_mediaplayer.addVariable("repeat","false"); archinect_mediaplayer.addVariable("showdigits","true"); archinect_mediaplayer.addVariable("showdownload","false"); archinect_mediaplayer.write("player");

(39:21) jourden >>> By bringing this archive to the web you have really, for many of us, made it new . Could you explain the mission of Ubu in light of this allusion to this statement by Ezra Pound?

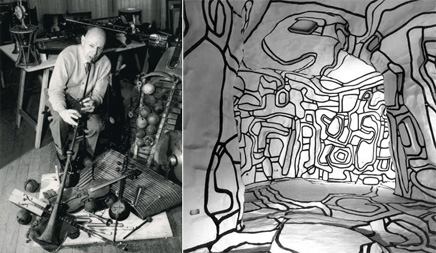

(39:51) goldsmith >>> I still believe what the Web does best is what it does originally, and that is just a way of getting things out and disturbing things. That is what's new about the Web. Programming, you know making computers jump through hoops isn't really very interesting to me. UbuWeb is a flat HTML 1.0 site. There is no programming behind it, absolutely everything is written in BBedit by hand. You know I want to keep the site very basic, because what really is new is this radical sense of distribution. We are in the business of radical distribution, and by that I mean--I get emails from people like one from a girl in Texas, who said "Thank you for what you put up on UbuWeb. And the type of materials you offer there certainly are not available to a girl living in a small town in Texas." You know, to me that is what it's about. That is what it's about! It really is about free and unfettered access for people to materials that were relegated to museums or relegated to specialist. And now are available to everybody free of charge. I mean there is a whole education to be had there. I think it's true. I think it takes a lot of this old stuff that had been forgotten about and I think in a sense it makes it new again. There has been so much revisionism in art history, so this is yet another sense of revisionism. You can look at this material and say "I never really thought about Jean Dubuffet as a musician before." And yet we have several files of Dubuffet . We know his art! Every museum has his art! But nobody knows he's a musician. It's very, very interesting--very beautiful. So yeah, I think it is--it does make it new. Very important, the other thing that is important to us, very much like your site [Archinect ] is that it's a beautiful place to be. That it's a clean and beautiful environment for the stuff to live in. There are some other sites on the Web that offer some similar stuff, a wonderful site called light and dust...

Jean Dubuffet with instruments and Jardin d'hiver 1969-70

(42:22) jourden >>> Hmmm I've never seen it...

(42:25) goldsmith >>> You wouldn't see it. It's a mess. It's really sort of the equivalent of an ugly, jumbled small press publishing, yet they offer really good materials, if you can possibly find your way through it. It's a nightmare and it's ugly. You don't want to be there very long. You know, a green page with red type on it; I don't know what they're thinking. The idea is to take these somewhat dusty old materials and kind of put them into a clean, well-lit environment so that they can really shine and be treated in a way that's serious, beautiful, and clean. Without all the clutter and grit that generally is attached to these things. I think that is a very interesting thing--suddenly it makes the avant-garde sexy in a way. Much of the materials that we are dealing with have been purposely against that. But when stripped of their original context and original packaging you simply have an mp3 file presented in a very beautiful place, I think it helps us to see them a little bit more objectively. Though a lot of the romanticism is lost I think that's okay. I think it objectifies the work.

(43:55) jourden >>> How do the different facets of the project come together, are each of the editors working independently of you the publisher or do you all collaborate on all the different portions?

(44:04) goldsmith >>> No, this is why we were unable to do a discussion like that. It's very disperse and people I trust--these editors Jerome Rothenberg , you know, invented ethonopoetics. Grey Lodge dot-org are a partner site with UbuWeb, are the film curators and their eye is absolutely impeccable. The access to the material they have is astonishing! And so forth, Otis Fodder with the 365 Days. So in fact, yeah, people want to share--Ubu has become the default source for a lot of stuff. People want to really share, and I have a good story about this--do we have time?

(44:52) jourden >>> Oh yeah we've got an hour. I mean but that is up to you though--how long do you want to stay?

(45:00) goldsmith >>> Well this is an amazing story. Have you seen Aspen Magazine on UbuWeb?

original Aspen Magazine Boxes

(45:15) jourden >>> Yes! It's awesome.

(45:08) goldsmith >>> Well I get an email submitted to Ubu anonymously-- it says, "Here is a site you might like to look at. It's called Understanding Duchamp dot-com ." Anything that is sent I look at, although most things don't get on the site. I'm hit very hard with submissions, but I look at everything--everything is viewed or listened to. And this is a nice little site about Marcel Duchamp done well in flash. I wrote him a little note back and say, "Hey man thanks that's cool. Good luck thanks for doing that."

He sends me another note that says, "Well if you like that you might like this." And he gives me the URL to Aspen Magazine that is online and password protected. And I look at it and go, "Oh my god!" I write him back and say, "What is up with this? This is absolutely incredible!" He said, "Well, I spent years digitizing the entire contents of the Aspen Magazine boxes and put them online. But what happened when I put Understanding Duchamp online I got a legal threat from the estate of Duchamp. Who evidently have a copyright on his name, and used Duchamp in the URL, and they really wanted to shut me down. I figured if that was the problem I had with Duchamp imagine the problem I'm going to have with six hundred other artists when I put them up on the Web." And I said to him, "Look you know what, why don't you give it to me. I'll take the risk, no problem, I know how to deal with cease and desists. You know I deal with them all the time." I explained the mission, "It's usually okay." Whatever, whatever, whatever...

So he gives me the whole thing and it's absolutely incredible. And on Aspen Magazine there are fucking files by John Lennon and Yoko Ono ! We have never heard from Lennon and Ono's people. And those real--you know who has more--but again this is the avant-garde, it's John Lennon's radio play, it's him twittering a dial and Yoko singing. Then the New York Times wrote up Aspen Magazine and they said to Merce Cunningham , who has an mp3 interview on there from one of the old records; "So Merce Cunningham, how do you feel about the fact that you were not asked permission but your work is up on UbuWeb?" And Merce said, "The educational value of having my words up on UbuWeb far outweighs any financial remuneration. I am thrilled that it's there." So that is the attitude, that's the attitude. That is basically what Robert Wilson was saying as well. Now of course we have people like that coming to us that want their works up there. The Robert Wilson guy said, "Hey you know we'd like to talk to you about putting more stuff up." And after this letter. [laughs] They understand the value of this site.

images from The 1965 International Design Conference from Aspen Magazine

(48:57) jourden >>> Ahhh I kind of want to go in this direction, to talk about commodity, the avant-garde, and the direction art is moving. Fredric Jameson , whom you've sung [laughs] has recorded that postmodernty--the condition of globalization, is a situation where "culture and the economic are folded back into one another " basically to a point where "culture becomes the economic and the economic becomes cultural. " In this context does UbuWeb function as an alternative force or is it merely a site to muse over as a relictoreum [sic]?

(49:36) goldsmith >>> I think Jameson is talking about a specific type of culture. And I think the other type of culture he's talking about the Madonna, Spielberg, that other type of culture. I really don't think he's referring to gift economies. Gift economies function outside of that type of economic theory. I believe it's an alternative certainly, but we didn't invent it, much of the Web functions on a gift economy. We just happen to be above ground with it. You know there are millions of file-sharing sites that are members only, that are password protected, that are anonymous, and I say look we're going to come above ground with this stuff. We're actually going to put it out into the light of day. We're not going to be bashful. Again I believe that we're not really part of Jameson's theory. I think he is talking about another model of economy and not ours.

(50:55) jourden >>> Right, but don't you think art in today's context, art becomes more of a commodity then it did in the past? In the sense that like you know, everything is a production, and everything is marketed like any other product. And even the resale value and this whole hype about...

(51:12) goldsmith >>> Poetry is immune to that.

(51:14) jourden >>> That's my other question [laughs]

(51:16) goldsmith >>> [laughs] It's definitely immune to it. I mean yes--something else--art yeah! You know Jeff Koons and the big show. This type of thing, but poetry for better or worse--and you could say it's detrimental or whatever it is, we are absolutely immune to that. As really is much of the avant-garde. John Cage is immune to that. John Cage is wonderful, but there is never going to be much of an issue of John Cage being a big deal. Ten years after his death he remains, as a somewhat obscure and legendary, but certainly marginalized as ever. It's unassimilable...

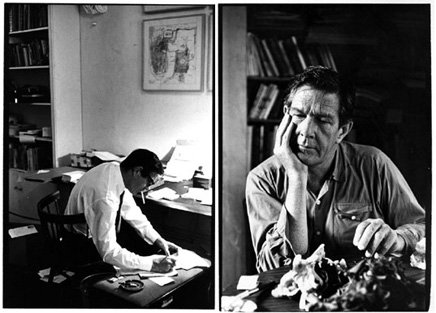

John Cage photographed by William Gedney 1967-68

(52:01) jourden >>> But still iconic, yeah?

(52:04) goldsmith >>> Extremely iconic and an extreme intellectual power, and great cred as they say, but there is no money there. It's going to be hard to fill a hall with music devoted to John Cage. The avant-garde, this is why it is so interesting because at a time of a complete commodification of art and a folding in of every type of art form even to the point where certain sacred rock songs are used on bank commercials, the avant-garde is un coupable. If it doesn't have a beat and it sounds like noise, it ain't going be on a car commercial anytime soon. And that's beautiful. It's still resistant. Dissident twentieth century music, a lot of this stuff is quite unassimilable, however, the avant-garde in painting, a Mondrian which is equivalent--no imagery, difficult for people, then sells for millions of dollars? That one I can't really understand. It's tough stuff. [Jackson] Pollock ? It's not easy.

(53:20) jourden >>> But it becomes a commodity because of the name of the artist, and not so much the content.

(53:24) goldsmith >>> But also because it's based on the laws of scarcity--there's only one of them. Where as our model is based on the law of plenitude--the more a book sells and the more copies there are the better the book does. It is a different type of model, the art world is scarcity.

(53:45) jourden >>> That's funny you really got right to the point here because I was going to lead in this, but is poetry the last bastion of art? Is it the only medium, which is completely resistant to becoming a commodity?

(54:04) goldsmith >>> Listen I think art still goes on and they make wonderful things. It's just mutating in terms of the economic, but that doesn't mean the art itself is bad. I mean [Takashi] Murakami or Koons, these mega-artists are making beautiful things, making beautiful productions in a different cultural climate, but it doesn't mean they're a sell-out! They're working with the system to create a new paradigm for art. This is something poetry will never have the chance to do. But I don't want to say that because...

(54:47) jourden >>> I wouldn't so much as call them a sell-out, but it's just that now the system caters to the super artist, so that it ultimately excludes...it likes the--just like architecture it likes the starchitects. It likes Frank Gehry , but it doesn't like the smaller people, and when those smaller people come it uses them up, then they disappear.

(55:09) goldsmith >>> Why is that different then mid-century Philip Johnson? There were four starchitects in 1950 and there are four starchitects today, and everybody else got eaten up. I think it's very much the same. I don't see it being any different! You think smaller architects got a shot back in the '40s?! Probably even less of a shot then they have today. Or artists even. I think because of the global expansion of the art world and the art market that everybody seems to get a shot. There are a lot more artists and they may not be stars, but they're making a living--they're showing and traveling, and they have fairly good careers as a result of this global boom. They're sort of trailing in the tail of the big guys, but it's good for everybody I think, it's really, really healthy. I think it's a great moment. My only regret though is that there aren't fifteen or twenty UbuWebs. I'm sorry we are the only ones doing what we are doing. But yeah it bothers me. Museums can't do it, because they've got to get permission. They've gotta get through hoops. They've gotta pay. They've gotta do contracts. They've got to do everything, and we don't have to do any of that shit! I haven't written a contract in my life for anything on UbuWeb. It doesn't exist! And by the way, the plug could get pulled tomorrow and the whole thing could vanish. We've come close...

(56:47) jourden >>> In terms of lawsuits or?

(56:50) goldsmith >>> Yeah, yeah or losing servers. We function on the good graces of donated bandwidth that are connected to universities. Once in awhile those plugs get pulled and we have to scramble for something else. I tell you the whole thing could just vanish tomorrow really. It's very unstable. We can't afford to pay the bandwidth costs. There are about 20,000 unique computers accessing that site daily. Downloading gigabytes worth of bandwidth, there is no way we could ever afford to keep this thing going if our university support dries up. And sometimes it does and we scramble to get another one. Fortunately, we are in a relatively stable state right now, but I don't know how long that will last. And really it could vanish, so download as much as you can because it could be gone tomorrow.

Listen to the response above. Get the Flash Player to see this player. var archinect_mediaplayer = new SWFObject("mp3player.swf", "line", "436", "20", "7"); archinect_mediaplayer.addVariable("file","download_as_much_ubu_5609.mp3"); archinect_mediaplayer.addVariable("repeat","false"); archinect_mediaplayer.addVariable("showdigits","true"); archinect_mediaplayer.addVariable("showdownload","false"); archinect_mediaplayer.write("player");

[laughs]

(57:51) jourden >>> In your manifesto you talk about poetry as "the perfect space to practice utopian politics." Does UbuWeb dwell in the fabric of desire to create utopia on the Web?

found on UbuWeb films: Le Cirque de Calder 1961 by Carlos Vilardebó

(58:52) goldsmith >>> It does. And it doesn't just speak it. It is it. There is no advertising. There is no money. There is no membership. There is no donate button. There is no mail list. We refuse to advertise, absolutely refuse to advertise, there is no nothing! And it's always been that way. And as long as I'm in charge it's always going to be that way. It's very important that it's an absolutely clean space with no ulterior motives. Because look if we start getting ulterior motives then we have to change everything we do. We have to start doing contracts. We have to start paying royalties. We have to start asking for permission. We have to have a staff. The only thing that we are real official with is that we are a nonprofit.

We actually went nonprofit, but we never did anything with it. We have a board, but we've never done any fundraising. I'm afraid to do fundraising. I'm afraid if money enters it, say we get a grant for $50,000 [big sigh] then you have to start managing the money. Then you have to start, I don't know what I'd do with it--I don't even want to think about it. [Ubu] thrives because it's based on love and passion. It has nothing to do with money. It's absolutely clean as hell, and that is just the way we intend to keep it. It's got all its arrows pointed in the same direction, and that is very important to us not only to preach it, but to be completely utopian.

found on UbuWeb films: The Girls of Kamare 1974 by Rene Vienet

(1:01:20) jourden >>> Is there a space for avant-garde architectural work on UbuWeb, and have you entertained any ideas for that?

(1:01:25) goldsmith >>> No. I don't know enough about it. But if somebody wants to do it, I say by all means. I'd love to see dance there. I'd love to see architecture there. I'd love to see theatre there. I don't know anything about these fields, but I welcome that. I think it would be absolutely fabulous to have somebody do that. And it's a completely scalable thing, it would take nothing to create a section for architecture, or dance, or theatre. As I understand it there are not spaces like this for theatre or dance, and perhaps, I don't know are there spaces like this for architecture?

(1:02:02) jourden >>> Ahhh...They're usually attached to institutions, but they don't put the stuff online as much. MoMA has some things that you can look at drawings and what not, but there is no text-based stuff. That's all for purchase usually. There are plenty of books that are out-of-print and in order to buy them they're $7000 or something.

(1:02:26) goldsmith >>> I think it would be fantastic. I mean why not? It would strike me that most avant-garde architecture is as much a gift economy as poetry is. I would assume, also that architectural drawings are as worthless as poetry, generally. A beautiful sketch by Frank Gehry might go for some money, but I can imagine a blueprint for one of his buildings is worthless. Yeah, I think that would be fantastic. If anybody you know is interested in taking that on, I'd be thrilled. We have unlimited bandwidth and unlimited server space.

(1:03:24) jourden >>> For now...

(1:03:26) goldsmith >>> For now, yeah by the way, you know it could always collapse tomorrow.

(1:03:32) jourden >>> In context to all of this where do see something like say Google scanning the whole New York Public Library. It seems like that is the next thing, right? Where these corporations end up sponsoring these types of things--maybe Google ends up with Google Obo or something?

(1:03:57) goldsmith >>> Well there is a great scene in 24 Hour Party People , did you see it?

(1:04:04) jourden >>> Yeah I've seen it.

(1:04:05) goldsmith >>> Okay at the end where EMI comes in to buy Factory Records, and everybody is excited--the EMI guys say, "We want to buy you for one million pounds." And everybody is like, "yeah, yeah!" So the EMI guys go, "Tony just give us the contracts." And everybody starts laughing. "What contracts?" Then the EMI guys start laughing because they know they are getting the entire thing for free. You know and that was it. We couldn't be bought. Google could never buy UbuWeb. It's the same story. Well show us the contracts. There's no contracts. So there is no danger of us ever being bought...

(1:05:48) jourden >>> They could make a competitor site?

(1:05:53) goldsmith >>> Oh fuck, let them, let them! Oh geez let them who cares! We have nothing to lose. I mean who cares. Like I said there should be many more of those. Who gives a shit! None of it matters. It's like punk rock. It's like punk rock. Who gives a shit, we'll burn tomorrow. We're not in it for--there is no future plan for it other then for it just to grow and become much better. Now somebody could just come in and say, "I want to take the site and have my staff go through and permission everything. We'll contact people. We'll pay people. We'll permission. We'll do the whole thing. Come on board we'll get the whole thing legit. We'll give you a salary and you'll keep directing it." At that point I don't know. But as that stands now it's a little bit of a joke.

Google scanning books? There's ulterior motives there man. It's sort of cool, but it's sort of not. I mean they're not doing it to benefit humanity. They're not practicing utopian politics. And I think the publishers have every right to be suspicious. You know, this is a huge corporation; they've got something else in mind. And again it's that other scale of economy that doesn't have anything to do with us really. And believe they ain't going to be scanning books that were produced in editions of one hundred that make absolutely no sense--guarantee! They ain't going to be scanning little books of Lyn Hejinian language poetry--I guarantee it.

The audio files for this interview are selected to offer the clearest moments of interaction between the participants. Since the interview was conducted in a public place, the moments of interference and pause have been omitted so as not to interrupt the flow or content of the interview.

Kenneth Goldsmith is an American poet. He is founding editor of UbuWeb , teaches Poetics and Poetic Practice at the University of Pennsylvania and is Senior Editor of PENNsound. He hosts a weekly radio show at WFMU and has published nine books of poetry.

Creative Commons License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License .

/Creative Commons License

3 Comments

MERZ!

Brilliant interview, John.

Goldsmith sits next to Perec on my shelf.

yes wonderful interview! thanx. although - and sorry, i don't want to be a stickler - but

difference between 'then' and 'than'??!...

eg:

'..interesting THEN the fabricating of certain objects..'

'..we're not in this for anything other THEN to get good works back into circulation..'

'..reason THEN that these categories are just collapsing..'

'..to say about it other THEN I've spent

becomes more of a commodity THEN it did in

Why is that different THEN mid-century

ess of a shot THEN they have today

no future plan for it other THEN for it just

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.