Molly Wright Steenson's introduction to the world of computing came when she was ten years old. From there, her career as a writer, designer, historian, and professor has taken her on a journey of understanding the past, present, and future of artificial intelligence and its relationship with architecture and design. Among her many contributions to the field include two books: Architectural Intelligence: How Designers and Architects Created the Digital Landscape (MIT Press, 2017) and Bauhaus Futures (MIT Press, 2019).

In May 2023, Archinect's Niall Patrick Walsh spoke with Steenson on how the relationship between artificial intelligence and architecture has shaped her career. We also reflect on how advances in AI through the 2020s sit within the decades-long history of the field and how architectural practitioners and educators could engage with AI in their own work. The discussion, edited slightly for clarity, is published below.

This article is part of the Archinect In-Depth: Artificial Intelligence series.

Niall Patrick Walsh: To begin, are you able to trace where an interest in computation first emerged in your life, and how it has shaped your career?

Molly Wright Steenson: I started working with computers in the 1980s when I was ten years old, and our family had an Apple IIe. Moving forward to college, where I majored in German and French, I spent significant time in the computer lab while serving as the entertainment editor of one of the newspapers. It was there that I was introduced to the World Wide Web in October 1994 and instantly realized how ‘big’ this was going to be. That encounter set me off on a path that, in some ways, I am still on. I’m still looking at the emergence and possibilities of digital media, how it can connect us to people we care about, and how it can allow us to create things together.

As the emergence of the web began to inform the fields of user experience design and information architecture, I was one of the early individuals to engage with those fields through the 1990s and early 2000s. In 2003, I became a professor at the Interaction Design Institute Ivrea in Italy, where the Arduino Board was invented. Throughout the school’s existence, I believe there were 80 to 100 students who went through it. This close-knit group changed how I thought about the digital and about the possibilities of architecture. After that, I attended grad school at Yale and Princeton for architectural history and was awarded my Ph.D. at Princeton.

From there, I became a journalism professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison before moving to Carnegie Mellon University. At CMU, my home department was the School of Design and an affiliation with the School of Architecture. The university awarded me the inaugural K&L Gates Associate Professorship in Ethics & Computational Technologies in 2018. I was really interested in the possibilities of building research capacity and was the Senior Associate Dean of Research for the College of Fine Arts from 2018–2021, and then became the university's Vice Provost for Faculty from 2021–23. I'm now stepping outside CMU for a very different role, as the President and CEO of the American Swedish Institute in Minneapolis starting in late July.

A formative encounter occurred for me while I was writing my dissertation at Princeton. During my research on the history and role of information in architecture, I found one footnote in Christopher Alexander’s book Notes on the Synthesis of Form, which addressed artificial intelligence. This sparked a curiosity for me. From 2000 through 2007, many were talking about cybernetics in architecture and architectural history, but nobody was talking about AI. I wanted to learn about that.

The relationship between AI and architecture is old enough to receive Social Security in the United States. It’s part and parcel of the contemporary practice of architecture and architectural modernity. — Molly Wright Steenson

So, from 2007 onwards, I have been researching the history of AI and computation in architecture. It’s a rich history. Marvin Minsky, who co-founded what became the MIT AI Lab in 1959, spoke at the influential Architecture and the Computer conference in 1964 in Boston. Walter Gropius provided opening remarks, and Christopher Alexander offered a closing essay. Douglas Engelbart, who invented the computer mouse, talked about the ‘augmented architect’ throughout 1961 and 1962. The relationship between AI and architecture is old enough to receive Social Security in the United States. It’s part and parcel of the contemporary practice of architecture and architectural modernity.

This relationship, and its history, is something I’ve been wrestling with recently. The popularization of recent generative tools from Midjourney to ChatGPT has created a whirlwind of interest, debate, and speculation on the broad topic of AI, and I’ve been trying to place these recent developments in a historical context.

In the present moment, when we see something new, we tend to regard it as a peak of innovation, even an 'end of history' moment. I feel that placing new-age AI developments in this historical timeline is an important exercise for understanding whether we are indeed on the cusp of a seismic shift in architecture, design, and labor, or if we are instead seeing a relatively incremental step in the gradual digitization of our profession, or even our society, when we zoom out to a timeline of years or decades.

I think about this a lot. Silicon Valley and the contemporary press have a tendency to blow things up. When you observe how AI is spoken about in the press today, AI is always presented as being ‘new.’ We’ve conducted studies that examine thousands of articles on AI from the perspective of ethics, data, governance, robotics, and other keywords, and ‘newness’ is always a common feature. It is interesting that we often consider AI to be new when we coined the term in 1955. On one timeline, it stretches back to World War II. But on another timeline, human notions of external intelligence date back over 2000 years.

Let’s begin with two statements: ‘AI is always new,’ and ‘AI is not new at all.’ The timeline of AI is interspersed with AI Winters of boom-and-bust cycles. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, AI research could be organized into a series of ‘micro worlds,’ which were small bounded universes that each contained a particular technology that researchers were advancing. These technologies could range from computer vision or edge detection to robotic arm manipulation or natural language processing, etc. These innovations worked in their own small worlds but didn’t necessarily scale up; a reality that many realized by 1973 with the publication of the Lighthill report. This began one AI Winter, when funding for AI research declined. Following this decline, AI research becomes tied to defense funding, which enters another cycle. After that, it becomes tied to expert systems, and so on. The history of AI is, therefore, a series of boom and bust cycles, often littered with hype that doesn’t deliver.

AI and architecture needed each other in order to necessitate technological development. — Molly Wright Steenson

Relating this history to architecture is interesting. People working within AI and computation have always sought out architecture as a way of describing their influence on the world. In essence, they are ‘world-building.’ In addition, architecture, CAD, and computer graphics required data, which required processing, which necessitated the development of computational environments which needed money and support. AI and architecture needed each other in order to necessitate technological development. You can also consider the perspective that the history of computation in architecture is a set of tendencies. I’m beginning to see this as more of a ‘cycle’ than a ‘timeline.’

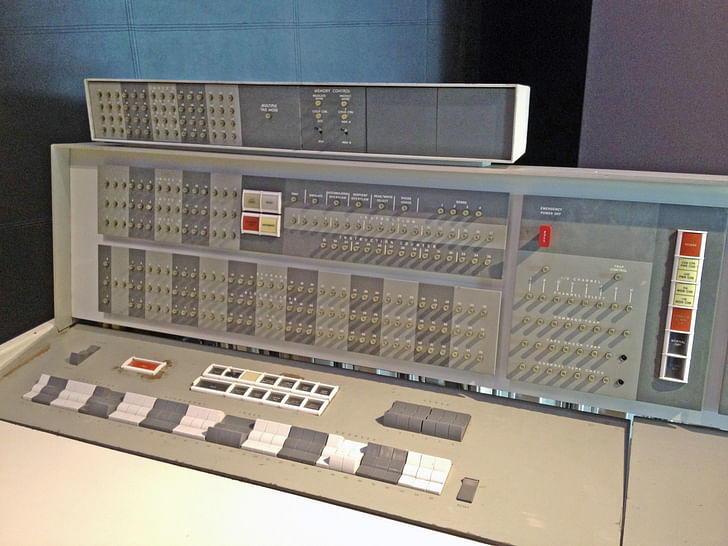

In the 1950s, Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill had a computer, and Harvard and MIT operated a joint computer center housing the IBM 7094 that Christopher Alexander used. But beyond this, computers were difficult to access and afford. In this first era, computers were used for risk engineering calculations, structural engineering calculations, and other mathematical problems. In the next era, we started to see the development of computer-related design, such as the Sketchpad 2 and Sketchpad 3, which was three-dimensional. At the same time, computer graphics was being accelerated by William Fetter and Boeing, where data was being represented by forms such as Boeing Man. There is a representation angle to this work, but I believe they were engaging with ideas of generativity and generation, too. The idea of generativity in architecture also stretches back to Nicholas Negroponte’s thinking about The Architecture Machine in 1970. This reading is what fuels my observation that the history of computation, representation, and generativity can be read in waves, or as a ball, rather than a linear, incremental timeline. They are all long-standing ideas in our discipline, and they all work together.

The relationship between architecture and AI is a longstanding timeline that contains tendencies. There are hype cycles and crashes. We’ve seen moments like this before, but the scale of this cycle may prove much larger. — Molly Wright Steenson

This brings us to the landscape of 2023, and the advances you referenced earlier. I was recently speaking with Rebecca Fiebrink, a computer scientist and Professor of Creative Computing who researches and builds tools for machine learning and creative practice, and lectures at University of the Arts London on creative computing. I asked her if this moment was similar or different, and she told me that she thought it was different. So if we package all of this, we can say: The relationship between architecture and AI is a longstanding timeline that contains tendencies. There are hype cycles and crashes. We’ve seen moments like this before, but the scale of this cycle may prove much larger.

Another crucial element to this history, and a question we must always ask today, is: ‘Who is funding this?’ Funding cycles for AI have moved through the US government, the Department of Defense, the Office of Naval Research, and then to the corporate world, before returning to the Department of Defense, and so on. What do these funding sources tell us about AI trajectories? Who is benefiting from this trajectory? These are important questions to ponder as we unpack AI’s relationship to architecture and beyond.

This question of how architects and designers can inform AI development is one which you confronted in your book Architectural Intelligence, where you wrote: “Designers and those who are concerned with user experience could exercise an impact on AI in several ways, particularly around the issues of automation, agency, and control, on one hand, and bias, trust, and power on the other. Designers can make interactions more transparent and can contribute to the ethical development of the systems with which they interact.”

I’m conscious that this was written while reflecting on a 2017 symposium of yours on ‘The User Experience of Machine Learning,’ but I’m curious as to how you see the potential, or necessity, for architects in 2023 to engage with how AI tools set to impact our profession are created and powered?

The world is indeed a different place in 2023, with a sort of hockey stick acceleration and impact of computational technologies. In 2017, the dominant term in these conversations was ‘big data’ rather than ‘artificial intelligence.’ There is an important relationship between these terms; AI requires an enormous amount of data.

At the very least, we should have an understanding that there are questions to be asked. — Molly Wright Steenson

I’ve always been of the opinion that designers of all kinds deal with the interface of technology in the world. Architects, in particular, are designing where technology meets the world. We design the buildings, the cities, the elements and details through which people move; environments that people interact with and are shaped by. The implications of these responsibilities are enormous. If you think about an iceberg in the ocean, we find ourselves designing the small portion of the iceberg that sticks above the surface, but we must be cognizant of everything below. It is absolutely necessary for architects to understand the impact they have on the world, including calling into question how AI tools operate, the nature of the data they use, and how such tools interact with the physical world. At the very least, we should have an understanding that there are questions to be asked. Just as we ask deep questions about architecture’s role in sustainability and climate, we should ask about its role in data, bias, and AI applications. I believe architects have much to say about this.

I’ve been thinking heavily about how the design process for AI applications differs from that of architecture. In 2018, Carnegie Mellon launched a new undergraduate degree in artificial intelligence. The structure of the curriculum was described through a series of concentric circles. The center of the curriculum was occupied by core computing languages. A further ring was human-computer interaction, and ethics was a part of the outermost ring. It struck me that if such a curriculum was modeled after that of design or architecture, it would be the opposite. You would find ethics of computation and systems at the core, and from there, you would build on the human-computer interaction, and then computational languages.

There are voices in our profession who are keen on surveying the tech world and saying: “That is not architectural.” My response is: “You are wrong.” — Molly Wright Steenson

From this, I began to consider that a responsible design process is a sphere that contains both cores working in tandem to create a holistic whole. The issue here is that it can be difficult to force computer scientists to slow down and consider these ethical questions. Earlier in 2023, Microsoft disbanded its Ethics & Society team, while in 2022, Facebook disbanded its Responsible Innovation team. On the other side, it is difficult to convince architects and designers to upskill and work in an environment more like Meta or Google, and less like architecture studios and ateliers. There are voices in our profession who are keen on surveying the tech world and saying: “That is not architectural.” My response is: “You are wrong.”

One of the landscapes in which this tension of 'what is and isn’t within the purview of architecture' plays out is academia. How do you believe AI should sit within an architectural education?

In some ways, it already has found a place. Sometimes, I purposely use the term ‘advanced computation’ as opposed to ‘artificial intelligence,’ which means we are then talking about the role of advanced computation, or emerging computational methods, in architectural education. I believe we already have tools built into architectural pedagogy, history, theory, and practice that allow us to explore emerging methods. Architecture is great at turning things upside down and looking at issues and topics from many different dimensions and rhetorical positions. You can ask questions. I believe this is what AI requires.

If every time you say ‘AI,’ you have to instead say ‘computer,’ it forces you to question what else you have assigned to that paradigm of ‘computer’ and what your expectations of it are. — Molly Wright Steenson

I recently interacted with a studio at Carnegie Mellon operated by Dana Cupkova, where students engaged with various image-generation platforms and interrogated the outputs. I reviewed a selection of the projects and was struck by how engaged the students were in their work, and in the complications that it opened up. Sometimes you see a student get a spark, and you know they are really ‘in’ their project. There was a lot of that. There was this mixture of confusion and excellence that a good design studio accommodates. So many questions emerge from this exercise that students can interrogate: What does it really mean for text generation to be a primary tool in architecture? What of issues such as representation, bias, copyright, and consent?

Zooming about, I would again remind architectural educators who are teaching a course on AI right now that AI can be viewed as another word for computation. If every time you say ‘AI,’ you have to instead say ‘computer,’ it forces you to question what else you have assigned to that paradigm of ‘computer’ and what your expectations of it are. Of course, we know AI is more than a computer, but I believe it is important to scale down our current hype cycle in order to understand more holistically the negative and positive possibilities of AI.

What happens when computers sink into the world around us? This is one of the reasons why architects should be on the frontline. — Molly Wright Steenson

Either way, architects cannot divorce themselves from the presence of AI. There is a diagram on page 110 of my book Architectural Intelligence which was created in 1989 by Jonathan Grudin. It depicts how computers have ‘reached out’ over time. Computers began as a mainframe, then became a printout, then a terminal, before reaching into a person’s brain, and then into an invisible social sphere around us. This question of ubiquitous computing is one of the topics that drew me to architecture. What happens when computers sink into the world around us? This is one of the reasons why architects should be on the frontline.

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

4 Comments

AI (ANI) is tool to help create architecture, nothing more. It's neither good or bad. I think any pushback that's being experienced is similar to the animosity towards AutoCAD, Revit, Sketchup, ect. It's just a fear of change due to not understanding the technology. I'm sure some people will try and use the tech to make 'quick and dirty' architecture that will not perform well. In that instance it's the fault of the architect, not the program.

AI is great ------ if you don't need to pay your rent.

Maybe your Landlord (or Mortgage Lender ) likes being jilted...

Care to expand on this? I'm not sure what you're trying to say and don't want assume anything.

In terms of a "boom and bust cycle",as a grad student,i recall reading Negroponte unrealistically expected to enroll a computer into his architecture class. Some in the field later turned to developing CAD. Without degrees in math and computer science, i am not competent fort his work, but always believed that any AI requires an extensive data base of 2D/2D plans based upon building categories. On a basic , not easy level, a data base of parking layouts would eventually yield a program to do the parking for your building. Building data bases from simple to complex would be developed and organized. The processing for the computer plus programing would be the difficult tasks. 50 years later, i am less enthused about all this and will not be around for the big changes 50 years hence.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.