Historically, Ireland's architects have punched above their weight on the world stage. Be it the White House in Washington D.C., innovative World Expo pavilions in New York, or Stirling Prize-winning buildings in the United Kingdom by Dublin-based Pritzker laureates, we explore how the island's architectural history and attitudes have informed what has today been dubbed the "golden age" of Irish architecture.

For a country of five million people, Ireland can claim a disproportionately large footprint on the world stage. It is estimated that more than 70 million people around the world claim Irish ancestry, including 31.5 million U.S. citizens and 20 U.S. presidents. In addition to this strong diaspora, the country itself possesses a deliberate will to infuse its values with the international community; a motivation which extends back to the foundation of the Irish Free State (now the Republic of Ireland) in 1921 following independence from the United Kingdom.

Since its founding, many of Ireland’s leaders have articulated this vision in their own words. In 1922, one of the country’s founders Michael Collins declared Ireland’s national aim to serve as a “shining light in a dark world.” Forty years later, Irish Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Seán Lemass noted that “Irish people are citizens of the world as well as Ireland,” and that “events in all parts of the world, and new ideas and developments everywhere, can be of direct and immediate interest to our own people.”

This exporting of Irish culture extends beyond the geopolitical to include the arts and sciences. Ireland claims several of the world’s most celebrated authors including Oscar Wilde, James Joyce, and Jonathan Swift, and Nobel Prize-winning writers such as William Butler Yeats, Seamus Heaney, and Samuel Beckett. Among the country’s famous scientists are Robert Boyle, one of the founders of modern chemistry, and Ernest Walton, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist who became the first scientist to artificially split the atom along with his colleague John Cockcroft in 1932. Dublin-born structural engineer Peter Rice, meanwhile, has been described as one of the most imaginative and gifted structural engineers of the late 20th century, making possible some of the world’s most celebrated architectural works including the Centre Pompidou, Sydney Opera House, Lloyd’s of London Building, and the Louvre Pyramid.

Before the 21st century, it could be argued that Ireland’s most notable architectural achievements arose from the ambition of a new state to establish a progressive, outward-looking identity on the world’s stage.

While the fields of art and science have demonstrated Ireland’s capacity to export ideas abroad, much of the country’s architectural history could be seen until recently as the opposite; consistently informed by influences imported, even enforced, from Britain and continental Europe. The island’s historic architectural fabric is nevertheless significant on the global stage. Some structures on the island date back over 3,500 years, including the famous Grange stone circle which dates before Stonehenge or the Great Pyramids of Giza. As history progressed through the Middle Ages, Ireland’s landscape would become dotted with castles and towers built by the Normans and Elizabethan English, planned towns built by British settlers, and most prolifically, British-influenced Georgian architecture which still forms an anchor for major Irish towns and cities today.

Arguably one of Ireland’s most significant architectural exports before the 1900s was the architect James Hoban. Born in Ireland in 1755, Hoban emigrated to the United States at the age of 30. In July 1792, Hoban was awarded the commission to design the White House in Washington D.C., overseeing the construction of one of the world’s most recognizable buildings. Hoban’s design for the White House drew inspiration from Leinster House in Dublin, which today serves as the Irish parliament building. A primary precedent for the White House’s original stone-cut exterior, the first and second floors of Leinster House were also used by Hoban as the basis for the internal layout of the White House.

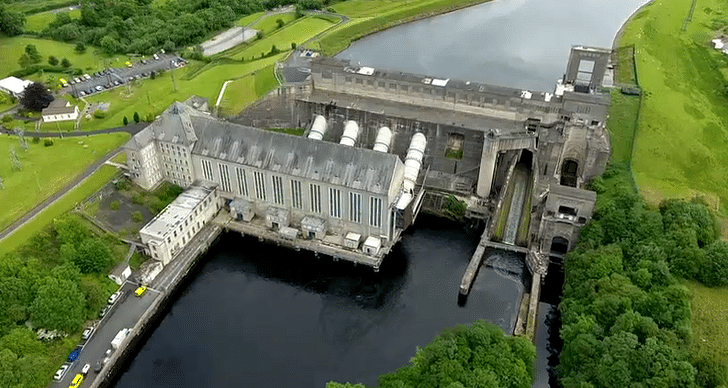

Following independence from Britain in 1921, the new Irish Free State (which formally became the Republic of Ireland in 1949), would increasingly look to European modernism for its architectural cues. The most significant project of this period was Ardnacrusha Power Station on the River Shannon in County Clare, designed by the German company Siemens-Schuckert. Commissioned only three years after the establishment of the State, the project was the largest in Ireland’s history, and the largest hydroelectric power station in the world when completed in 1927. “It was a vast and ambitious undertaking for the new Irish government, but one which was to mark an important commercial and political for it, greatly enhancing the international reputation of the new state,” wrote architectural historian, Dr. Paul Larmour. “Its architectural form was equally impressive, with a large steel-framed and concrete-walled power station, reminiscent in its tall windows, steep pitched roofs, and overall mass, of pre-First World War industrial work in Berlin, such as the AEG factor complex by the pioneering German modernist Peter Behrens.”

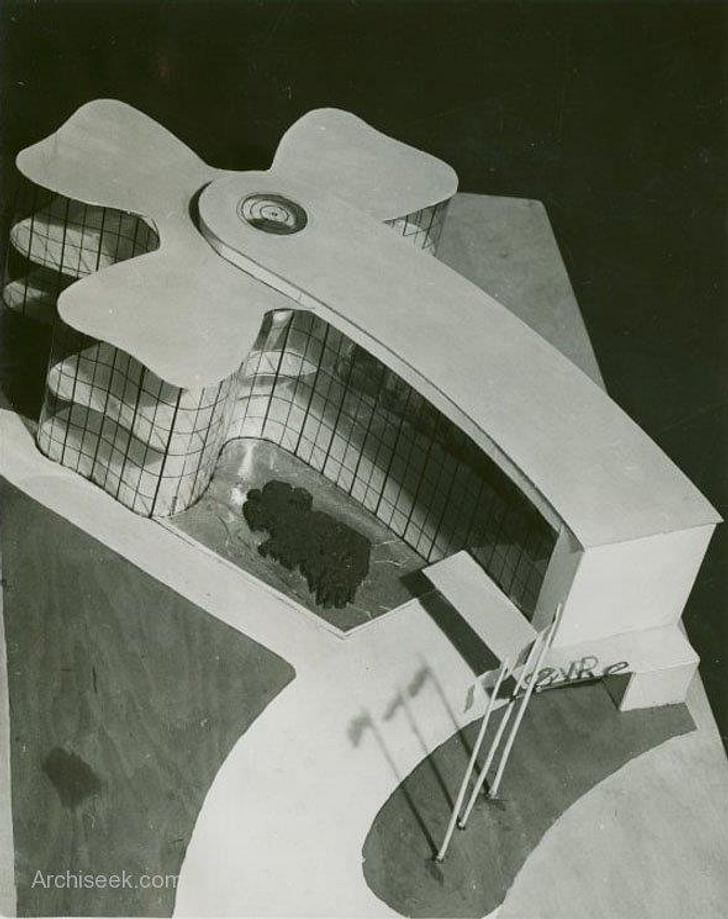

1939 saw Ireland make its first appearance at the World’s Fair as an independent country and another opportunity for the new state to establish a unique national identity and character. The task fell to the Irish architect Michael Scott, founder of the still-functioning firm Scott Tallon Walker. Scott’s design for the Irish Pavilion of the 1939 World’s Fair in New York was as innovative as it was elegant; constructed of steel, white-painted stucco, and a glass curtain walling system among the most advanced of its time. When viewed from above, the curvilinear pavilion deliberately resembled a shamrock, Ireland’s national emblem, representing one of the earliest examples of a building designed to be viewed from an airplane in the burgeoning age of commercial aviation.

A more significant intersection between aviation and Irish architecture came two decades later with the establishment of the Shannon Free Zone in 1959. While the nearby Shannon Airport had historically served as an important ‘gateway’ between America and Europe due to its location on Ireland’s Atlantic coast, it was recognized by the 1950s that advances in aircraft fuel efficiency meant that most flights between the two continents would soon bypass the airport. To secure the region’s economic future, the Shannon Free Zone was established as a defined region adjacent to the airport with special tax exemptions and tariff reliefs to attract foreign investment. Shannon thus became the world’s first Special Economic Zone (SEZ), establishing a model which would later influence the creation of over 5,000 SEZs around the world today, most notably Shenzhen, China.

A new generation of Irish architects has ascended to the pinnacle of global architectural discourse.

Before the 21st century, it could be argued that Ireland’s most notable architectural achievements arose from the ambition of a new state to establish a progressive, outward-looking identity on the world’s stage. Today, these government-led initiatives have been surpassed by the emergence of a new generation of Irish architects who have ascended to the pinnacle of global architectural discourse; leading what eminent Irish journalist Fintan O’Toole has dubbed the “golden period” of Irish architecture.

Leading this trailblazing group are the 2020 Pritzker Prize laureates Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara of Dublin-based Grafton Architects. The second Irish winners of the Pritzker following Kevin Roche in 1982, Farrell and McNamara have collected almost every major architectural award there is. In 2008, Grafton’s Universita Luigi Bocconi in Milan was crowned World Building of the Year at the inaugural World Architecture Festival, followed four years later by the Silver Lion Award for their contribution to the 2012 Venice Biennale. Farrell and McNamara would return to the event as the co-curators of the 2018 Venice Biennale with the theme Freespace. In 2020, the duo was awarded the RIBA Royal Gold Medal, followed one year later by the 2021 Stirling Prize. The firm’s ever-growing portfolio embodies the international reach of contemporary Irish architects, from their UTEC University campus in Lima, Peru to their School of Economics for the University of Toulouse, France, to London-based educational buildings at Kingston University and the London School of Economics.

Grafton is joined on the world stage by O’Donnell + Tuomey, led by Dublin-based Sheila O’Donnell and John Tuomey. 2015 winners of the RIBA Gold Medal, shortlisted for the Stirling Prize on five occasions, and six-time exhibitors at the Venice Biennale, the practice has established a national and international reputation for their signature style of sharp-lined geometric forms and bespoke masonry arrangements. Among their significant works is the Lyric Theatre in Belfast, for which the pair won the 2021 RIAI Gold Medal, and international projects such as the Central European University in Budapest and the LSE Student Centre in London. Both Grafton’s and O’Donnell + Tuomey’s founders are also linked by their international engagement with education, with their domestic professorships at University College Dublin accompanied by visiting lectures at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. In the context of the gender inequalities evident through the histories of both Irish society and the international architectural community, it is perhaps an additional point of pride and promise that three of Ireland’s four most acclaimed architects are women.

Given the caliber of Ireland’s contemporary architects, Irish citizens could be forgiven for feeling short-changed.

The deliberate intertwining of Ireland’s economy with that of the international community is not without its peril. The 2008 global recession was pronounced in Ireland, whose economy was left exposed by a toxic blend of subprime mortgages underwritten by national and international lenders who were controversially bailed out by the Irish government at the Irish taxpayers’ expense. As architectural writer and Archinect contributor David Capener noted in The Irish Times, the recession saw one-third of Ireland’s architectural firms lay off between 61% and 100% of their staff. However, from the ashes of the economic crash, a new generation of Irish architects has once again emerged, already following the examples of Grafton and O’Donnell + Toumey to lead a national and international architectural discourse. “As practices closed their doors, a number of younger architects emerged who have gone on to define a new movement of modern Irish architecture,” writes Capener, whose Archinect feature on the subject has celebrated the works of young post-recession firms TAKA, Clancy Moore, and Steve Larkin.

Given the caliber of Ireland’s contemporary architects, however, Irish citizens could be forgiven for feeling short-changed. Despite an ever-growing list of accolades, commissions, professorships, and curatorships awarded by the international architectural community to their Irish peers, there remains an irony that many of Ireland’s most capable architects are unable to bid for major domestic projects in Ireland itself. As a member of the European Union, Ireland must abide by EU-crafted policies on appointing architects for publicly-funded projects; policies which many argue Ireland has interpreted excessively stringently. Irish architects seeking a school project, for example, may only be eligible for such a commission if they have designed several domestic school projects in recent years; a rule which serves major corporate firms over the small-to-midsize architects who have become the public face of Irish architecture to the world, including Grafton Architects and their portfolio of award-winning international educational works. “The biggest blockage is opportunity,” Grafton co-founder Shelley McNamara told The Irish Times in 2019. “It puts a lid on talent and creativity. It’s seriously inhibiting the generation next to us.”

It is still shocking that the architects who are making great buildings all around the world are an unwanted resource in their own country.

For a country whose young history is littered with examples of national governments recognizing the role of architecture in cultivating a progressive national identity, there is a sad irony to the present reality. Today, access to major public architectural projects in Ireland is at its most exclusionary, at a time when Ireland’s architectural caliber has arguably never been stronger, and when the contribution of these same architects to the architectural identity of international cities has never been more recognized or valued.

“It is still shocking that the architects who are making great buildings all around the world are an unwanted resource in their own country and in many cases in their own city,” protested journalist O’Toole, in the same Irish Times article within which he praised Ireland’s “golden period” of architects. “We have the sites, we have the money, and God knows we have the need. What we don’t have is the vision. But if we lack the vision, we do have the visionaries.”

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.