Around the world, cities and citizens continue to suffer from the effects of air pollution. While the COVID-19 pandemic ironically led to a temporary improvement in urban air quality, the status quo for the air we breathe in cities is bleak. In this article, we examine the prevalence, causes, and effects of air pollution in urban environments. In a concluding note of optimism, we also highlight examples of architects using their skills to enhance air quality in cities and improve the health of both humans and nature.

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken a heavy toll on the world’s population over the past year, be it through high death rates, a disruption to basic supplies, or global economic harm. One consistent anomaly throughout the pandemic, however, has been the apparent inverse effect of COVID-19 on the natural world — popularized by footage of unprecedentedly clear water in Venice’s canals, or a radical decrease in the number of animals being killed due to human activity, particularly transport and shipping.

One of the most universally observed silver linings of the past year has been a noted improvement in urban air quality. “It’s positively alpine,” exclaimed one resident of Delhi, India, quoted in a 2020 article by The Guardian detailing the fall of air pollution in major cities. This relief was echoed in South America. “The thick cloud that usually hangs over us has been lifted,” said a resident of Cali, Colombia. “The concern is that it will return with the quarantine ends.”

Although COVID-19 has indirectly led to a reduction in air pollution in cities, the European Society for Cardiology believes that 15% of deaths worldwide from COVID-19 could be directly or indirectly attributed to long-term exposure to air pollution.

While the influx of photographs showing the “then versus now” of cities during COVID-19 is both novel and surreal, it is also an unsettling window into how polluted our cities’ air quality was before the pandemic, and what it will likely return to when the pandemic passes. In 2018, the World Health Organization estimated that 90% of the world’s population breathed polluted air, with 7 million people dying every year from exposure to fine air particles, which can induce strokes, heart attacks, lung cancer, or respiratory infections including pneumonia. In fact, while COVID-19 has indirectly led to a reduction in urban air pollution, the European Society for Cardiology believes that 15% of deaths worldwide from COVID-19 could be directly or indirectly attributed to long-term exposure to air pollution.

For the purposes of this article, we shall specifically examine air pollution from particulate matter in an urban context. While rural areas can fare worse than urban areas by some environmental metrics, notably water quality, organizations such as the CDC (USA) and Center for Cities (UK) have concluded that air pollution tends to be worse in cities. From an architectural perspective, a focus on air pollution in cities also affords us the opportunity to understand the role of architecture and design in causing air pollution, and the ever-increasing examples of architects employing their skillsets to understand and tackle the issue.

The causes of air pollution in cities are a blend of global and local issues. The World Health Organization notes that many cities across the world share the same major sources of air pollution, such as the “inefficient use of energy by households, industry, agriculture, and transport sectors, and coal-fired power plants.” Vehicular traffic is a particularly prevalent source of urban air pollution. National Geographic notes that vehicles produce one-third of all air pollution in the United States, making them the largest air quality compromisers. To compound this prevalence, the air pollution emitted from vehicles is generated at street level in closer proximity to humans, in contrast to air pollution from industrial processes which may linger at higher altitudes.

Vehicles produce one-third of all air pollution in the United States, making them the largest air quality compromisers.

However, not all air pollution in a given city is created by that city. In the UK, for example, high levels of air pollution in south-eastern cities such as London are partly due to air particles blowing across the English Channel from continental Europe. The generic causes of air pollution in cities can also be exacerbated by local conditions. For instance, Los Angeles holds the undesirable accolade of having America’s worst air quality partly due to the significant mountain ranges located to its north and east, which traps air particles in low-lying urban areas. Frequent wildfires across California also contribute to LA’s poor air quality — an anomaly which also captured global attention in cities across Australia during the country’s notorious 2019/2020 wildfires.

Air pollution generated by citywide infrastructures can be compounded further by “indoor air pollution” generated within the home. The World Health Organization notes that more than 40% of the world’s population does not have access to clean cooking fuels and technologies in their homes, relying on wood, gas, or oil-burning systems which contribute to particulate pollution.

The United Nations estimates that the 1970 Clean Air Act and subsequent amendments in 1977 and 1990 have prevented over 230,000 deaths in the United States from poor air quality.

As our understanding of both the causes and dangers of air pollution in cities has increased, so too have regulations surrounding it. The United States has been steadily regulating air pollution since the introduction of the 1970 Clean Air Act; placing restrictions on the use of known dangerous pollutants. The United Nations estimates that the legislation and subsequent amendments in 1977 and 1990 have prevented over 230,000 deaths from poor air quality. Over the past 30 years, the volume of harmful chemicals floating through the air of American cities has also dramatically declined, including carbon monoxide (74% decrease), ground-level ozone (21% decrease), and lead (82% decrease). Despite these efforts, the United States remains the leading country in premature pollution-related deaths.

Across Europe, meanwhile, dozens of cities have banned or restricted the use of cars in urban centers to combat air pollution. In London, an “Ultra Low Emission Zone” now covers most of the city center, where cars must meet high emission standards or pay a daily charge. The city’s air pollution laws have also been cast into the spotlight recently after a court ruled that air pollution “made a material contribution” to the death of a nine-year-old girl in 2013. The girl, Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah, thus became the first person in the UK to have air pollution listed as a cause of death. It is anticipated that this ruling will embolden efforts to both reinforce and strengthen air pollution laws in the United Kingdom, and serve as a precedent for other legal jurisdictions.

As lawmakers across the world continue to enact tighter restrictions on air pollution, the architectural community has taken a growing interest in developing ideas which can measure, or combat, air pollution. In particular, the financial and knowledge resources needed to measure air quality in cities can be beyond many municipal governments, with the World Economic Forum citing that only half of the world’s governments produce or share such data.

To aid this endeavor, architects are utilizing their mapping skills to understand the extent of air pollution in cities around the world. In Barcelona for example, where lawmakers are already removing cars from one-third of streets, local architects have created the “Air” project to better understand the city’s air quality. The project, curated by Olga Subirós, began as a proposal to represent Catalonia at the 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale. “As part of one of the largest and most influential international architecture events, our project highlights the essential role of architects in drawing up new cartographies that can represent new ways of thinking about our cities and also change the current model of the city that has so far prioritized economy over health,” Subirós told Forbes. “As architects, we must redraw cities to make their complexity visible; we must include what is invisible, including the negative of what was built: the air, an apparently empty space invaded by human action and filled with atmospheric pollution that endangers the survival of our species and non-human species.”

Meanwhile, the MIT Senseable City Lab has engaged in similar efforts. Their 2018 “Weibo Smog” project sought to understand the impact of air pollution on human activity in 251 Chinese cities by using 50 million geo-tagged Weibo check-ins (China’s equivalent to Twitter). One year previous, in 2017, the group unveiled the findings of their “Clean Air Nairobi” experiment, which deployed six low-cost air quality monitors across the Kenyan capital, demonstrating the ability of low-cost sensors to provide indicative measurements of air quality that are valuable for local communities.

As many cities experience warming temperatures, increased storm frequency, and continued air pollution, the well-being of our urban trees has never been more important.

The MIT Senseable City Lab’s examination of air quality has also extended to urban ecology. Recognizing the importance of trees and vegetation as natural air filters for cities, the Lab created the “Treepedia” database to allow dwellers from ten global cities to view the location and size of trees within their communities, and to submit input to help tag, track, and advocate for more such trees. “As many cities experience warming temperatures, increased storm frequency, and continued air pollution, the well-being of our urban trees has never been more important, says Carlo Ratti, Director of the Senseable City Lab. “Through Treepedia, we present an index by which to compare cities against one another, encouraging local authorities and communities to take action to protect and promote the green canopy cover.” Earlier this year, the Lab built on their research with “Diversitree,” seeking to understand the street tree diversity and spatial variation patterns across eight global cities. The open-source data generated by the study is intended to enable practitioners to better target tree diversity efforts, for the betterment of everyday city dwellers.

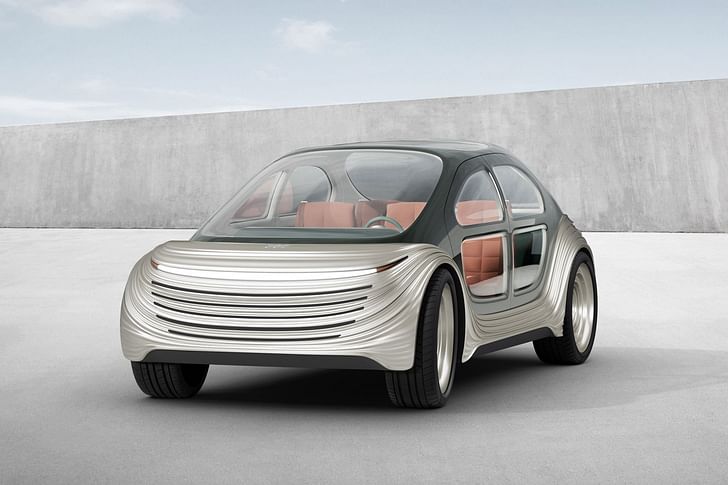

Other architects have approached the issue of air pollution through specific architectural forms. These include Studio Symbiosis’ “Aũra” purifying towers, designed to alleviate air pollution in Delhi, India. Aũra’s system of air-purifying structures, ranging between 18 and 60 meters in height, is composed of two purifying chambers, topped by a green planter, and covered by a spiraling lattice façade. While the 60-meter-tall structures would form a perimeter ring around the city to prevent the flow of air pollution to the surrounding environment, the smaller 18-meter-tall structures would be interlaced throughout air pollution “hotspots” across the city, responding to local needs. Meanwhile, at last month’s Shanghai Motor Show, Heatherwick Studio unveiled “Airo,” an autonomous electric car equipped with a state-of-the-art HEPA filtering system that actively cleans the air surrounding it. If brought to market, the integration of transport and air filtration could form a powerful mitigation measure against the street-level particulate pollution described earlier in this article.

Ultimately, the approach to tackling air pollution is one of dualities, combining local and global measures, artificial and natural systems, embodied design, and operational use. While architects and policymakers continue to advance legislations, measure conditions, and propose a variety of measures that clean our polluted air, a successful long-term campaign must recognize air pollution not as an isolated phenomenon but as a symptom of broader flaws in how cities are built, used, and powered. As a familiar, hazy shroud returns to our cities in a post-pandemic world, symbolizing the “fog of war” waged on both nature and ourselves, it may further our clarity on the need to design buildings, infrastructures, and cities that draw on natural, renewable, and circular systems to both construct and operate them.

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

4 Comments

it's misleading to view air pollution as a distinctly urban problem that can be solved through interventions within individual cities. that view is a nineteenth century perspective when pollution came chiefly from factories located in dense urban centers.

now it's a broad systemic problem and involves much larger issues of economic development, fuel sources, regional industrial policy, and agricultural management. there is nothing useful a single city can do independent of the surroundings and how they manage industry (especially heavy industry and power generation, which are largely ex-urban systems).

i think the above image shows well that pollution doesn't cluster around single cities - it grows in belts thousands of miles across corresponding to large scale weather systems. desert dust and wildfires are a substantial factor too in some regions.

The initial spread of COVID in rural Netherlands indicate that air quality and pollution is also a rural thing, the areas with more air quality reducing farms such as poultry and pig farms were more severely affected than other similar rural areas with other types of farming/ air pollution...FYI my 2 cents.

Talking about a smog city:

Sad how all pollution remedies are based on technological fixes instead of reduction of noxious activity solely because there is no financial profit in downsizing. For example the idiotic preference for personal electric vehicles over public transit without concern for how the electricity necessary to power them is generated or for delivery losses of 60% and more over antiquated power grids.

The decline in air pollution due to decreased activity from covid is exactly the same as the improved atmospheric effects that resulted from the brief air travel ban after 9/11 - proof that decreasing the amount of harmful activity is the most obvious - and most directly effective - way to address these matters.

For architects this should mean adaptive re-use, traditional passive features, smaller buildings, renewable materials, etc. Provide passive cooling in hot climes and yes, wear a fucking sweater when it's cold. But architects are just servants providing the amenities that their masters desire, and if they don't the breadline awaits.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.