Deans List is an interview series with the leaders of architecture schools, worldwide. The series profiles the school’s programs, pedagogical approaches, and academic goals, as defined by the dean–giving an invaluable perspective into the institution’s unique curriculum, faculty, and academic environment.

For this installment, Archinect spoke with Jeff Schnabel, Director of the School of Architecture at Portland State University, a 400-student program offering undergraduate and Master of Architecture degrees, including the possibility of an Integrated Path to Architectural Licensure track.

We caught up with Schnabel to discuss the school's ties to local design practices and initiatives, the importance of designing with darkness and night, and how the school is working to make architectural education more affordable for PSU's sizable first-generation student population.

Briefly describe Portland State University’s pedagogical stance on architecture education.

Since the school’s founding in 1995, the program has had a deep commitment to “making.” We believe that a student has a better understanding of their architectural representations if they have physically joined wood, cast a metal component, and built a form that withstands the pressure of liquid concrete.

We are also a product of our urbanity. Portland is a wonderful city in which to experiment and we take full advantage of that opportunity. We often refer to Portland as our laboratory because it is the subject for much of our experimentation. The city, with its energetic commitment to environmental sustainability and its vibrant arts culture, plays a significant role in defining our project types and responses.

Since the School’s founding in 1995, the program has had a deep commitment to “making.” We believe that a student has a better understanding of their architectural representations if they have physically joined wood, cast a metal component and built a form that withstands the pressure of liquid concrete.

What insights from your past professional experience are you hoping to integrate or adopt as the director?

As professor and the director of the school, I try to remind our students that it is not enough to have a great idea; you also need to be able to inspire others to be as excited by your proposal as you are. This requires that you become skilled at utilizing verbal, written, and visual clarity. This does not mean dumbing down the work. Instead, it is about bringing your audience along with your architectural narrative, no matter how simple or complex it is.

I also emphasize the importance of collaboration. The most successful results I had in practice came from a collaborative process; my work was made better by the contributions of others, particularly from those in disciplines other than my own. To that end, our students are given the opportunity to work with landscape architects, planners, and a full spectrum of engineers, both in the studio and through our Research-Based Design Initiative, where the students contribute to teams of professionals testing and designing for building performance.

What kind of students do you think are poised to flourish at PSU and why?

It all starts with curiosity. Skills can be taught, and work ethic can be nurtured, but the students who excel are the ones who desperately want to understand architecture’s full potential to serve and inspire.

For [first-generation] and many other students, working and/or caring for a child or parent while attending school is their only option—presenting a huge challenge given the time-consuming nature of architecture school. In many ways it is a reversal of when I was in school.

What are the biggest challenges, academically and professionally, facing students today?

Even at a public institution like Portland State University, the price of attending college is a major hurdle for many students. In our program, we are fortunate to be serving many first-generation students, who can feel intimidated by the challenges and expectations of higher education. For these and many other students, working and/or caring for a child or parent while attending school is their only option—presenting a huge challenge given the time-consuming nature of architecture school. In many ways it is a reversal of when I was in school. These days, studying architecture is often less stressful than life outside the studio.

What are some of the advantages of the school’s context—being at PSU and in Portland—and how do you think they help make the program unique?

For some time now, our students have migrated to projects that are in direct service to others. Portland, like many cities, is working to confront homelessness, drug addiction, socio-economic disparity, and the impacts of global warming. Our students have the opportunity to work directly with a full spectrum of design professionals, non-profits, and public agencies to determine where and how architecture can contribute. The PSU School of Architecture’s Center for Public Interest Design allows our students to take these same skills to domestic and international destinations, applying them in underserved and marginalized communities worldwide.

As an added challenge, we are preparing for an inevitable massive subduction zone earthquake that will be devastating to Portland. Our students are embedded in city-wide projects to prepare for, and recover from, this seismic event.

As an added challenge, we are preparing for an inevitable massive subduction zone earthquake that will be devastating to Portland. Our students are embedded in city-wide projects to prepare for, and recover from, this seismic event.

How would you like the school to have changed during your tenure?

I am dedicated to development activities that lighten the economic burden for our students. Because we are committed to embracing a diverse body of students, it is critical that we eliminate the financial roadblocks to an architectural education. That said, there are aspects of our school’s culture and pedagogy that I intend to protect: the joy that comes from successful creation and collaboration, and faculty members who respect, support, challenge, and enjoy each other. I feel an awesome responsibility to maintain the remarkable culture of this place. In addition, I hope to be our last white male director for a good stretch of time.

I am dedicated to development activities that lighten the economic burden for our students. Because we are committed to embracing a diverse body of students, it is critical that we eliminate the financial roadblocks to an architectural education.

The Pacific Northwest is a hotbed for mass timber design and manufacture, how is this new material/structural approach impacting the curriculum at PSU?

Portland architects are moving past just using mass timber for its efficiencies and performance and creating works of beauty and craft. Our students are being exposed to and educated in this work, and there is no question that we are seeing this technology being deployed more often in their projects. However, they are frequently reminded that in our pedagogy, the material is not the starting point for design—they should have clear intentions for meaning and human experience and then select materials that fulfill those intentions. That does not mean that they are free from the pursuit of human and environmental health. Architecture, unlike a building, must do both.

You have done quite a bit of work in the realm of lighting design, both with the Portland Winter Light Festival and the Willamette Light Brigade. How did you become interested in lighting design and what impact has this focus had on your design perspective?

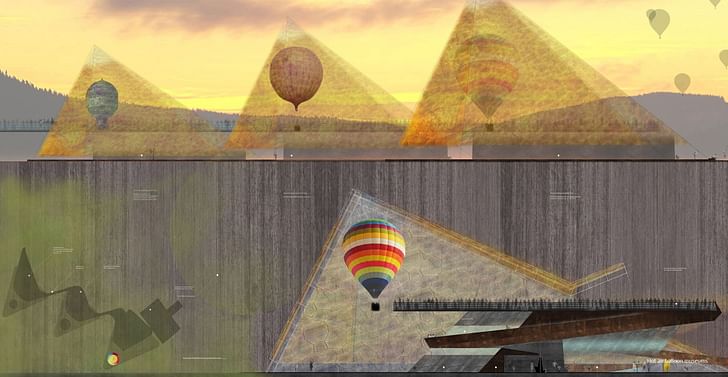

It all started as a collaboration I did with an art faculty member doing short films. We asked ourselves if surfaces could be enriched with projected light and if projected images could be made more meaningful if moved from a neutral screen to complex surfaces. So the architecture students in my class made interesting walls, and after dark we turned on the projectors. It was awful. For the next iteration we waited for dark, turned on the projectors, and manipulated the architecture to respond to the light. What started as a disappointment became magical. At this moment I realized that conceiving of architecture during the day and simply adding light to it at night was a missed opportunity. As a result, I tried having students begin with darkness in their work (including building physical models inside dark boxes). As I started looking for others doing similar work I realized that architects, landscape architects, planners, and engineers tend to conceive of their work solely as daytime places, despite the fact that we occupy darkness for significant portions of our lives. Darkness is a wonderful context—even sound changes in darkness. So, most of my creative activities are now dedicated to making the public realm successful after dark. I should point out that lighting turns out to be only a portion of those emerging strategies.

As I started looking for others doing similar work I realized that architects, landscape architects, planners, and engineers tend to conceive of their work solely as daytime places, despite the fact that we occupy darkness for significant portions of our lives.

PSU’s School of Architecture is housed within Shattuck Hall, a building originally designed in 1915 as a public elementary school that was renovated in 2008—How does the school benefit from being located within a public building from this era?

I largely inherited this wonderful building, Shattuck Hall. It was remodeled under the guidance of the former director, Clive Knights. What I can tell you is that it is a wonderful balance of new and old. The new fabric was added unapologetically. All the systems were exposed to serve as learning opportunities, and the innovative ceiling-based hydronic heating and cooling system was deployed—a very new idea, which continues to work quite well. The artist Mark Rothko attended elementary school in this building shortly after it opened, about a hundred years ago. If he returned, he would still recognize it despite the transformations that make it incredibly collaborative and flexible.

With the ascendant Green New Deal and other initiatives, some say we are heading toward an era of greater public sector involvement for architects. How might architectural education change under such a paradigm?

I don’t think it will feel like a change to us. So many of our projects are for and with public agencies. For example, we are part of a new initiative with TriMet (Portland’s public transportation agency), which is engaging our students in exploring projects that are out in front of their current planning. Multnomah County recently worked with our students to develop prototypes for an earthquake-resilient Burnside Bridge that could serve as an aid distribution center after the event. Portland Parks and Recreation is working with us on our new mobile place-making initiative, which will allow amenities to move from park to park. PSU’s School of Architecture is just three blocks away from the Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability offices, four blocks from TriMet and ten blocks from City Hall. They are not only our collaborators, they are our neighbors.

Antonio is a Los Angeles-based writer, designer, and preservationist. He completed the M.Arch I and Master of Preservation Studies programs at Tulane University in 2014, and earned a Bachelor of Arts in Architecture from Washington University in St. Louis in 2010. Antonio has written extensively ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.