Expelled from domestic spaces through cuts to social subsidies, layoffs, and the speculative real estate policies of the 1970s, the population of homeless individuals in New York has ballooned with the perpetuation of income inequality and long-term lack of affordable housing in the city. Despite increasing numbers, this social crisis has become less and less visible throughout the last decades [1]. In February 2017, the Department of Homeless Services estimated that 3,892 individuals spent the night in New York City streets [2]. Although the accuracy of this estimate has been contested [3], a comparison to the number of individuals sleeping in one of the 236 facilities of the city’s shelter system—a total of 62,435 [4]—makes us reconsider the “exposure” of public space as the privileged site of contemporary homelessness, and turn instead to a different architectural device: that of the shelter.

This shift can be situated circa 1979. Alarmed by the degrading conditions of the municipal Men’s Shelter in the Bowery, 27-year-old lawyer Robert M. Hayes gathered a series of homeless plaintiffs to bring a class-action lawsuit against the City of New York, forcing its Department of Social Services to guarantee shelter to any individual in need. On December 5, the New York State Supreme Court pronounced the first decision requiring the city government to alleviate the shelter crisis. To proceed with further actions, Hayes co-founded the advocacy group Coalition for the Homeless, which, in conjunction with the Legal Aid Society, developed in the 1980s a dense fabric of laws encoding the spatial relations of homelessness in New York City, and, thus, determining a role for architecture even in a social crisis seemingly defined by its very dispossession.

When addressing homelessness, architects’ anxiety for immediate transformation has eventually led to a misidentification of the scope of intervention. One of the usual responses to this social crisis has been the search for ultimate shelter-design solutions [5]. But to focus on the architecture of transitional shelters falls into the trap of the so-called “humanitarian aid paradox,” in which the momentary alleviation of suffering can prolong the causes that created these suffering conditions in the first place. In fact, urbanist Peter Marcuse alerts us of the dangers of understanding homelessness as a design problem. “To propose that an upgraded shelter will solve the alienation of the homeless is naïve and counterproductive,” says Marcuse, “it is factually wrong, and it distracts from the economic inequities that generated the problem” [6]. The belief that design excellence can amend the failures of political economy obfuscates the ideological decisions at the core of these failures. Yet, this does not mean that architects should withdraw from the discussion. As Marcuse points, their professional training, which “compels [them] persistently to re-evaluate our assumptions” [7], can be productive in questioning the conditions of housing and urban policies—reflecting on, rather than merely solving, the causes of homelessness.

The following conversation with Robert M. Hayes endeavors to recognize the architectural decisions encoded in the legal activity of New York City’s advocacy group Coalition for the Homeless. In exploring the architectural implications of legal architecture of homeless shelter policies in New York, a new critical space for architectural production in this area can be excavated. As the advance of neoliberalism increasingly leads to situations of inequality and precariousness, to recognize design as imbricated within a larger network of actors and institutions offers an alternative path to new critical, conscientious modes of practice.

LUIS ALEXANDRE CASANOVAS BLANCO: I would like to start by referring to the message that Martha Rosler famously broadcasted in the Spectacolor screen of Times Square in 1989: “Housing is a Human Right” [8]. The message rightly describes the legal engineering of advocacy groups to enforce the provision of assistance for individuals in need: shelter had first to be articulated in the form of a “right” [9].

Yet in the litigations that took place throughout the 1980s, there was a continuous back-and-forth between the recognition of this “right to shelter” and the definition of the material, spatial, and managerial conditions of the shelter to be provided. In some occasions, judges would recognize the right to shelter while failing to define its minimum standards. In other occasions, judges would not recognize the right to shelter, but would establish that, if provided, it should meet minimum standards. The legal demand for shelter was thus unbundled into a two-fold condition: on the one hand, when disassociating a political right from its material conditions, the notion of shelter was abstracted, obscuring its wider social and economic implications; on the other hand, when determining the provision of material resources without accounting for its political significance, the material support constituting the shelter was rendered as unrelated to the ideological operations to which rights belong [10].

My abiding principle, for starters, was for shelter to be, at least, meaningful

ROBERT M. HAYES: The right to shelter granted under the Callahan vs. Carey litigation was initially ordered by the court in 1979 without any specific quality standards [11]. My abiding principle, for starters, was for shelter to be, at least, meaningful. And that might sound ridiculous now, but certainly when the litigation started, there were many people who viewed homeless people as a matter of choice as opposed to a lack of alternatives [12]. The guiding criteria was that it had to be preferable to public space, to streets and subways. Even more, given the extremely unpleasant conditions of the first shelters set up under the initial non-quality court order. Thus, we demanded a Consent Decree—that is, a civil settlement reached by the parties approved by the court without a trial—to establish some minimum standards adding to the initial right to shelter in the Callahan preliminary injunction, finally approved in 1981. The criteria would be to set up a series of conditions that were, as one judge put it, “not palatial, but a cut above the streets.” It was not exactly an architectural or design decision.

LACB: This cut-above-the-streets quality—the interrogation of what domesticity means in relation to configurations of the public, and how the difference between the two realms is articulated seems to me an architectural question—a very important one. In fact, I think that the inefficacy of architects in engaging with topics such as homelessness is a consideration of architecture as separate (amongst many other realms) from legal discussions.

RH: Anyway, we could truly have resorted to the opinion of experts such as architects, social workers, psychologists, or psychiatrists to help the court define these conditions. And, at some point, as we could not agree on the maximum number of people that each facility should accommodate, we did have real testimony from architects. But, in fact, the whole principle of law argues that the duty of the court is to enforce policy, not to define it. Thus, we crawled to try to find what you may call in law as “justiciable” conditions; that is, standards that could be credible to the judge, and thus, enforced onto the right to shelter. We finally derived the shelter standards from regulations for adult homes run by the New York State Department of Social Services [13]. We convinced the judge that these should be applicable as they had been determined, after doing diligence, by the executive branch of government, not the judicial branch. And this is how we arrived at the very arcane standards that are still in place.

LACB: Despite that, in the decree, the overall definition of shelter is kept architecturally loose, the material and technical conditions of every single element that conforms the shelter space appear over-defined. For example, the decree states that a shelter space should be “substantially constructed, in good repair and equipped with clean springs,” furnished “with both a clean, comfortable, well-constructed mattress standard in size…and a clean, comfortable pillow of average size” [14]. The use of terms such as “clean” or “well-constructed” when talking about furniture suggests that common sense might not be implicit, and thus, a consensus on what a bed is needs to be achieved.

RH: Indeed, and it is embarrassing in retrospect… The whole negotiation with the judge was like a crazy trench warfare. At some point, we even argued about whether there was one sheet or two sheets—one to cover the mattress and an in-between linen under the blanket. And the city wanted one sheet. And I argued, “Well, if you are only going to have one sheet, are you going to wash the blanket for every user?” And that is how we got to two sheets, because the city would not have to wash the blanket every time someone used it [15].

The notion of shelter that you were first trying to enforce presupposed that, to be “meaningful” the shelter had to entangle a network of care and support

LACB: One of your initial requests when the Callahan vs. Carey litigation started was that the shelter provided should be “community-based,” a requirement that you finally dropped in negotiation. Thus, the notion of shelter that you were first trying to enforce presupposed that, to be “meaningful,” using your own words, the shelter had to entangle a network of care and support: it had to be inscribed within a preexisting social structure.

RH: Our demand for “community-situated shelters” responded to the aim of having facilities located in the main areas where homeless people were then concentrated. But it eventually evolved into questions of security and accessibility: we wanted to make sure that shelters would constitute a safe and accessible alternative, and thus, that individuals in need would make use of them.

LACB: This interestingly points to the idea of “community” as a granter of “safety”…

RH: Let me mention an interesting anecdote related to this demand. After the first court order came down, the municipality got the state government to cede the Keener Building, an abandoned psychiatric hospital under the Triborough Bridge on Wards Island. We, young idealists, thought this was abhorrent: to create a shelter on the grounds of a psychiatric institution, on an island in the middle of the East River, shoving humanity out of sight. And we were ready to try to block that, arguing that the operation was basically a sham: the building was inaccessible, and nobody would go there. But talking to some homeless individuals then living at the Bowery, I learned that those sheltered at the Keener Building were relieved to get away from the pressure and the stress of the hard-living conditions of the Lower East Side. They were welcoming the Keener Building as a refuge, from which they could walk across the bridge from Wards Island right onto Third Street in Manhattan. So sometimes our idealism did not converge with the actual demands of our clients.

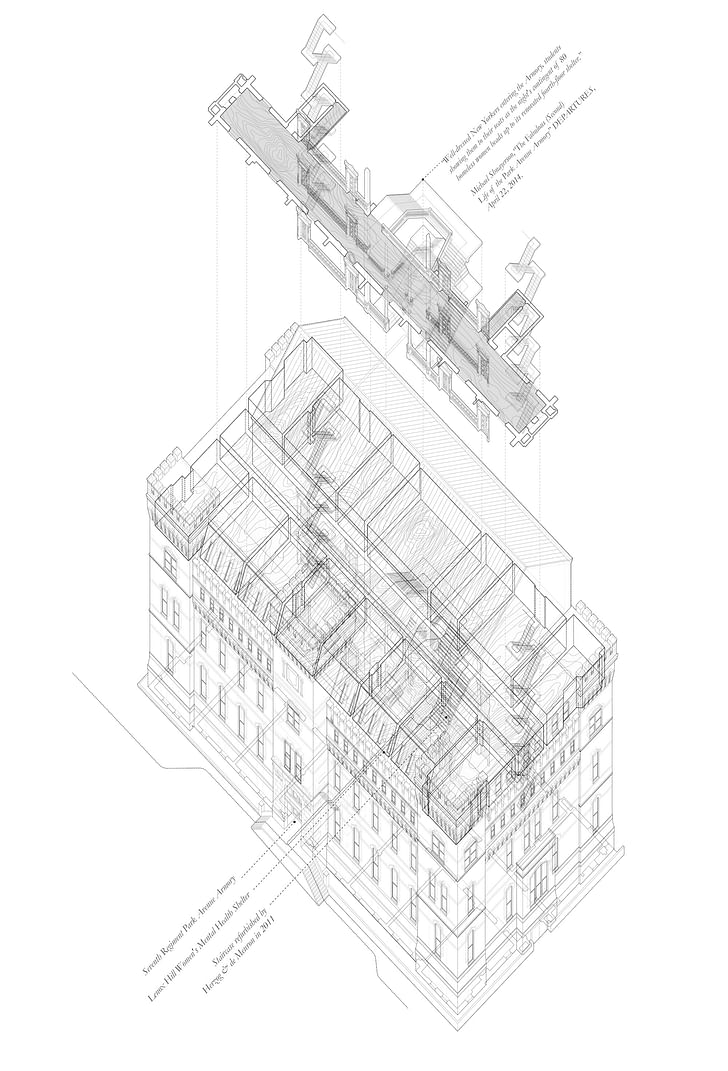

LACB: In the early eighties, the implementation of the Callahan vs. Carey resolution obliged a record expansion of the shelter system, including the reconversion of armories for sheltering purposes. You were strongly opposed to this decision.

RH: Well, at that point in time, they needed space. But they could have done a lot better. Much of my concern with armories was that they were too damn big. A quote that I was known for using and abusing was “big is bad; very big, is very bad.” And that is true, it is just a human thing.

LACB: So, could we say that your opposition was based, among other reasons, on architectural or spatial conditions? To put it more specifically, on questions of scale?

The bottom line was to make sure that every bed was secure, seen as safer and less undignified than living in public space.

RH: Only in part. It had more to do with keeping limited the number of beds in any facility. The city was in desperate need for beds, for sure. But, for me, the bottom line was to make sure that every bed was secure, seen as safer and less undignified than living in public space. Thus, being one person in a 1,000-bed armory, like it happened in the shelter at Fort Washington, was not acceptable. We ended up using the number 200, although this number is, of course, relative. If we think of a shelter as an open for all, ward-like space, above two hundred beds would be awful. And even two hundred is awful; it is still too many. Yet, it would be different if we had a 250-unit Plaza Hotel-like space. Take for example, the Prince George Hotel, which is now a supported housing program run by the non-profit Breaking Ground for individuals formerly homeless or at risk of being homeless, where you have 416 units. This number would just not work in a congregate setting. That is the reason behind the plumbing ratios which, to this day, remain a matter of contention. The proportion, which established that “there shall be a minimum of one toilet and one lavatory for each six residents and a minimum of one tub or shower for each ten residents,” was used as a tool to keep the overall volume of beds in a shelter as low as possible. This way, you could have a billion square feet space, but if you only had ten toilets, then you could only shelter a hundred people there.

LACB: At the current moment, pressure is being added from various sectors to shift discussions around the “right to shelter” to embracing the “right to housing.” In a way, this convergence between housing and shelter erases the notion of emergency ingrained in the provision of shelter, as well as reasserting the sense of normality inscribed in that of housing. In so doing, it illusorily depicts homelessness as a temporary disjuncture of the sociopolitical system to be amended, while I believe it is pretty much part of its logic.

RH: Well, the difference between shelter and housing can indeed be debated, and maybe an architect can do it better than me. It did not take very long to recognize that the right to shelter was not a good endpoint. It is always going to be a sort of stopgap, anything but a way station to a better solution. So, how you depart from it, in which direction you move to truly palliate the problem rather than just responding to a situation of emergency is something that every New York administration has struggled with ever since the Callahan vs. Carey litigation. For example, Mayor [Edward I.] Koch, in office during the litigation, once told me that he considered that the major achievement of his administration was to invest into building up the city's stock of available housing, recovering abandoned tenements in Bushwick, South Bronx, or the Lower East Side. But he did not remember that his administration initially opposed [this]. In fact, Koch himself strongly opposed [this] until we made a quite convincing political case that investing in housing instead of continuing to pay the outlandishly expensive cost of shelter was not just the right measure to do, but also an economical measure to take. In fact, shelter as a minimum, legally-enforceable right was eventually used politically to push the agenda for housing. The increase of affordable housing as a consequential achievement from the right to shelter court order may have been more valuable than the right to shelter itself.

LACB: One of the issues that I believe is of extreme significance in dealing with socially-sensitive topics and disenfranchised populations is the role that one, as an outsider to the everyday of these realities, should play, as you want to avoid “speaking for others.” In the early days of the Coalition, you insisted that the advocacy group’s work had to significantly depart from the attitudes and strategies of what you then referred to as the “mainstream charitable industrial complex.” And yet, the Coalition has been often criticized for acting as a delegate actor of the actual sufferers of this social crisis, for not integrating enough the voices of those unhoused.

RH: It is not easy. And probably, I am still not politically correct on some of those questions. Hopefully then, hopefully now, it all starts with being respectful of the individual. I always recognized that I was, in a sense, a delegated advocate. I had never been homeless or poor, and I never had to put those working boots on and fight that battle. The Coalition, and me personally, supported many organizations across the country led by people who were or had been homeless. The trouble with having the requirement of homelessness to have credibility, leadership, or ownership of that kind of organization is that, aside from survival, when you are homeless it is hard enough without trying to change the world. At the end of the day, a homeless person does not want to be homeless for long. Her entire energy is focused on getting out of that state. But I believe that if you are in a position where to be a credible voice of homelessness you must be homeless, you are very quickly going to become an outlier and not representative of homeless people any more than I might be. Although I acknowledge the contradictions in this argument, I still believe there is a little bit of truth in it.

It is through its mere presence in the street that homelessness threw into question the prevailing societal and political system

LACB: The political significance of the homeless individuals as a collective has been largely debated; and, as you mention, there are examples throughout the country of activist groups led by homeless individuals themselves, or with an important participation of them.

There is, though, an alternative way in which the political impact of homelessness has been discussed, and which I believe is truly of importance to architecture: its mere visibility in public space. It is through its mere presence in the street that homelessness threw into question the prevailing societal and political system, showing its flaws and contradictions. Ultimately, if the presence of homeless individuals on the streets in the 70s and 80s was widely theorized as a transgression of the social construct of public space, the reabsorption of these individuals into the architectural interior demands an interrogation of contemporary notions of domesticity [16]. The huge number of sheltered subjects signals a reabsorption of homelessness back into the architectural interior from which they are understood to be expelled in the first place (their identification as “home-less” points to a lack). Fostered by the articulation of a state and municipal legal framework, collective understanding of homelessness has shifted from one inextricably associated with public space to one constructed by a new domestic architecture. With homeless people in permanent transit through a network of more than 236 municipal shelters throughout New York City, these subjects’ dissociation from visibility on the streets and subsequent inscription within the architectural interior urges us, in a more explicit way than ever, to reassess our modes of practice when engaging with vulnerable populations.

If you liked this article, you'll love Ed #2 ~ get your hands on a copy of Ed #2 The Architecture of Disaster here and the Archinect Outpost!

[1] Ian Frazier has already asserted that the lack of awareness of this crisis is a consequence of the invisibility of current homelessness, internalized within the shelter’s architecture: “[Most New Yorkers] say they thought there were fewer homeless people than before, because they see fewer of them.” Ian Frazier, “Hidden City,” The New Yorker (October 28, 2013) 39.

[2] The data comes from the Homeless Outreach Population Estimate (HOPE), a point-in-time, citywide survey conducted annually by volunteers under the supervision of the New York City Department of Homeless Services (DHS). The aim of HOPE is to produce an estimate of the total number of unsheltered individuals living in the streets of New York City.

[3] The survey has received criticism from various non-profit organizations, which accuse the municipality of strategizing a minimization of the problem through the survey’s methodology.

[4] The most recent available data of individuals spending the night on the NYC Shelter System is from November 2017, accounting for a total of 63,169 sheltered individuals. To be able to compare the number of sheltered individuals with that of unsheltered individuals, I resorted to the most recent available data for unsheltered individuals, released on February 2017. Data: NYC Department of Homeless Services and Human Resources Administration and NYCStat shelter census reports. “Facts about Homelessness,” Coalition for the Homeless website, accessed January 22, 2018 http://www.coalitionforthehomeless.org/the....

[5] One could even say that the situation described in Krzysztof Wodiczko’s Homeless Vehicle Project (1988-1989), a series of space-age trolleys which ironically placed design as complicit with urban inequality and the production of disenfranchised individuals, nightmarishly became the dominant discourse in architectural interventions trying to engage with situations of precarity. In this regard, see Rosalyn Deutsche, “Krzysztof Wodiczko's Homeless Projection and the Site of Urban ‘Revitalization,’” in Evictions: Art and Spatial Politics (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1996), 3-48; and Dick Hebdige, “The Machine is Unheimlich: Wodiczko’s Homeless Vehicle Project,” in Public Address: Krysztof Wodiczko (Minneapolis, MI: Walker Art Center, 1991) 54-67.

See, for example, the 2015 AIA SPP Small Project Design Competition. The Pop-up Project: A Safe Place.” The competition brief avoided any political reference to more endemic causes of homelessness, merely reducing the crisis to “an extreme consequence of poverty.” The competition proposed the use of a street pod “as the first step [for homeless individuals] toward getting things back in order and on a path to the life they want to lead.” (Italics my own) https://network.aia.org/smallp... (accessed January 24, 2018).

[6] See Peter Marcuse, “Criticism or Cooptation: Can Architects Reveal the Sources of Homelessness?” Crit: The Architectural Student Journal, Issue 20 (Spring 1988), pp. 30-32. The text was written in response to a review at the Pratt Institute School of Architecture on the inter-studio “Homeless at Home,” comprising different schools and organized by the association Architect, Designers and Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR). For background information on this event, see: Tony Schuman, “Reflections of a Still Radical Studio Critic, or Goldberger got it wrong: Social Issues in the Design Studio,” in Debate and Dialogue: Architectural Design and Pedagogy. Proceedings of the 77th Annual Meeting of the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture, Chicago, ed. Tim McGinty and Robert Zwirn (Washington, D.C.: Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture, 1989) 346-350.

[7] Marcuse, “Criticism or Cooptation,” p. 32.

[8] This project was a commission of the Public Art Fund under the project “Messages to the Public.”

[9] For an accurate description of the legal strategies adopted by Robert M. Hayes, see Kim Hopper and L. Stuart Cox, “Litigation in Advocacy for the Homeless: The Case of New York City” Development: Journal of the Society for International Development 2 (1982): 57-62.

[10] My reading of the “right to shelter” is here informed by Michael Ignatieff’s account of human rights advocacy. See: Michael Ignatieff, “Human Rights,” in Human Rights in Political Transitions: Gettysburg to Bosnia, ed. Carla Hesse and Robert Post (New York: Zone Books, 1999) 313-324.

[11] Callahan v. Carey, No. 79-42582 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. County, Cot. 18, 1979). Online: http://www.coalitionforthehome... (accessed January 21, 2018).

[12] The epitome of this attitude is President Ronald Reagan’s own comments on this social crisis. In an interview in the television show Good Morning America in 1984, Reagan stated that "the homeless . . . are homeless, you might say, by choice.” Sydney H. Schanberg, “New York; Reagan’s Homeless.” The New York Times (February 4, 1984). Online: http://www.nytimes.com/1984/02... (last accessed February 4, 2018).

[13] Hayes refers here to 18 N.Y. Comp. Codes R. & Regs. 491.2: Official Compilation of the Codes, Rules and Regulations of the State of New York. Title 18: Department of Social Services. Chapter II: Regulations of the Department of Social Services. Subchapter D. Adult-care Facilities. Part 491. Shelter for Adults.

[14] Callahan vs Carey Consent Decree. August, 1981. Online: http://www.coalitionforthehome... uploads/2014/06/ CallahanConsentDecree.pdf (accessed January 21, 2018).

[15] The administrative staff in charge of applying the consent has explained how, by then, they would constantly have all sorts of “Kafkaesque discussions” around the life-cycle of objects in the shelter system. The anecdote of the “mystery of the short-lived sheets” is particularly telling. Apparently, the city had to resort to the Department of Corrections’ municipal facilities at Rikers Island to comply with the required high volume of laundry capacity. When leaving the building, guards punched the packaged sheets with sharp bayonets to detect any hidden detainee trying to escape, tearing the linens. Thomas J. Main’s interview with Bonnie Stone, the first assistant deputy at the municipal Human Resources Administration (HRA). October 2011. Quoted in Thomas J. Main, Homelessness in New York City: Policymaking from Koch to de Blasio (New York: New York University, 2017) 42.

[16] See: Peter Marcuse, “Neutralizing the Homeless.” Socialist Review, 18(1) (January, 1988), pp. 69–97. ; Rosalyn Deutsche, “Agoraphobia,” in Evictions: Art and Spatial Politics (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1996) 269-376.

Lluis Alexandre Casanovas Blanco

Lluís Alexandre Casanovas Blanco is a New York and Barcelona based architect, curator and scholar. He was the chief curator of the Oslo Architecture Triennale 2016 together with the After Belonging Agency, and he is currently a PhD Candidate at Princeton University, and a Critical ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.