For the past six years, AIA New York has been hosting an intoxicating series of dialogues that pairs an architect with a critic, journalist, curator or other design professional to discuss design over a custom-crafted cocktail. What began as an informal, casual Friday evening event for architects, has evolved and resulted in a treasured catalogue about how to design.

Titled Cocktails & Conversations: Dialogues on Architecture, a recently published book put out by AIA New York and the Center for Architecture showcases a selection of these conversations from over the years. From Justin Davidson talking with Charles Renfro, to Michael Kimmelman interviewing Jeanne Gang, the book excerpts these provocative conversations alongside napkin sketches and recipes for featured cocktails. Here, we feature a chat between OMA Partner Shohei Shigematsu and journalist Amanda Dameron. The two discuss specificity and process-oriented design over a bourbon drink known as the Brown Derby, named after the famous Hollywood restaurant. Grab yourself a rosemary sprig, pour a stiff one, and read the resulting exchange below.

Shohei Shigematsu is a Partner at OMA and Director of the New York office. Since joining the firm in 1998, he has been a driving force behind many of OMA’s projects, leading the firm’s diverse portfolio in the Americas for the past decade with emphasis on maximum specificity and process-oriented design

Amanda Dameron is a design journalist and producer. She served as editor-in-chief of Dwell magazine from 2011 to 2017, and now leads Home and Design for Tastemade, a digital-first media company with a global audience of 200 million. She has held editorial positions at Architectural Digest and Western Interiors and Design.

BROWN DERBY

By Eben Klemm

2 oz. Bourbon

1oz. Grapefruit juice

1/2 oz. Rosemary honey syrup

Add ice and shake 20 times. Strain over fresh ice into a rocks glass and garnish with a rosemary sprig.

Rosemary Honey Syrup:

Simmer 5 fresh rosemary sprigs in 1/2 liter water for 5 minutes. Dissolve in 1 liter honey.

The Brown Derby, an unlikely successful combination of bourbon, grapefruit, and honey, is one of the few cocktails actually named after a bit of architecture. The Brown Derby, a restaurant for 1940s Hollywood swells, was shaped like the hat, and the drink itself, interestingly, wasn’t served there.

PROCESS, PROGRESS, AND EVOLUTION

SS: OMA is a design-oriented firm with a global reach. It is no longer capable of being curated by a single mind. The partnership structure lends itself to independence and individuality within the firm. At the same time, the office and its organizational centers share a way of thinking. By orienting towards a process that observes changes in society, the architecture incorporates these changes. At OMA New York, we engage clients with specificity, narratives, and a collaborative spirit that allows us, in turn, to push the boundaries of known typologies.

AD: You allude to community presentations. An essential part of building is listening to the inevitable feedback that comes. I’m wondering, as part of your practice, do you attempt to insulate yourself from such critical feedback as you know it will come no matter what you put out there, or is it helpful to you as part of your practice?

SS: At OMA, we are self-critical. By constantly interrogating ourselves throughout the design process, we develop a robust way of explaining and defending our concepts. Architectural moves are, at times, difficult to communicate to people, especially to a larger audience. We try to convey our concepts and schemes as boldly as possible through diagrams, books, and narratives. When doing so, we are conscious of absorbing critical comments and responding in the most engaging way, encouraging collaboration whenever possible.

AD: It’s almost as if you anticipate this feedback—you position yourselves in a practice arena so that you are ready, like the presidential candidates do to prepare for a debate. Often it’s said that, as part of the architectural curriculum, it’s important to maintain a tough skin. Criticism is such an important part of a curriculum.

You have chosen to work with artists and as part of collaborating with them, it’s acknowledging performance.

SS: The great thing about working with an artist is the unexpected framework that would not be possible as architects alone. There

are also different kinds of challenges that come with working with artists,

as opposed to other clients. In a way, the same rigor and creative processes

that artists go through, in turn, push us to redefine typologies and boundaries of tradition. What is a theater? What is a museum? How are these

typologies responding to our changing environments, and how should

architecture be a conduit for manifesting these changes?

For the Marina Abramovic Institute in Hudson, New York, our design was very much driven by the artist’s mission to cultivate new kinds of performance. The building would be dedicated to radical explorations of time-based and immaterial art, and the design aims to expand on the educational and institutional typologies. We proposed a new type of theater, surrounded by auxiliary program spaces. The new space provides a monastic ground that is both highly flexible and controlled. Three areas around the theater allow it to expand or be reconfigured.

There was a time when great architects had to have a manifesto. Today, I think it's not about one big idea, but more about observation of societal changes and reflecting those changes in architecture. OMA is hyper-aware of the environment around us and, in turn, we do not have a homogenous design language. We appreciate cultural knowledge and sensitivity, and encourage design to be derived from specificity—site, budget, client, program, and climate—and not to be stylistic.

It was a very refreshing experience to collaborate with Taryn Simon on

“An Occupation of Loss” at Park Avenue Armory [in 2016]. She brought

an intense and meticulous rigor to the project that resonated with us.

The project was the culmination of three years of research and thought.

Dealing with grief and representing loss was an interesting challenge

for us. Not only was it a challenge to respond to an emotionally charged

topic, but grief is also carried at diverse scales. As we discussed the scale

of representation, we wanted to avoid “installation” as an “architectural

exercise,” but rather as a sonic exercise. Putting aside the aesthetic nature

of architectural installations, we devised a concept that was at once

monumental and intimate. It was also an interesting challenge to create

something functionless, with no rules. In this instance, our installation was

a vessel for the mourners.

When I came to New York 10 years ago, I tried to establish a new culture inspired by the firm’s Rotterdam office, but acting independently. Being in New York and away from Rotterdam enables me to pursue my own ambition while continuing the culture and practice of the firm. The firm is no longer capable of being curated by a single mind, but we still carry on the rigor and process that started in OMA Rotterdam.

My ambition is to capture conditions specific to our generation, and through those observations, create new architectural typologies. I want to immerse myself in key moments and turning points of institutions and other clients, and design buildings that will reflect their beliefs, contributing to their evolution.

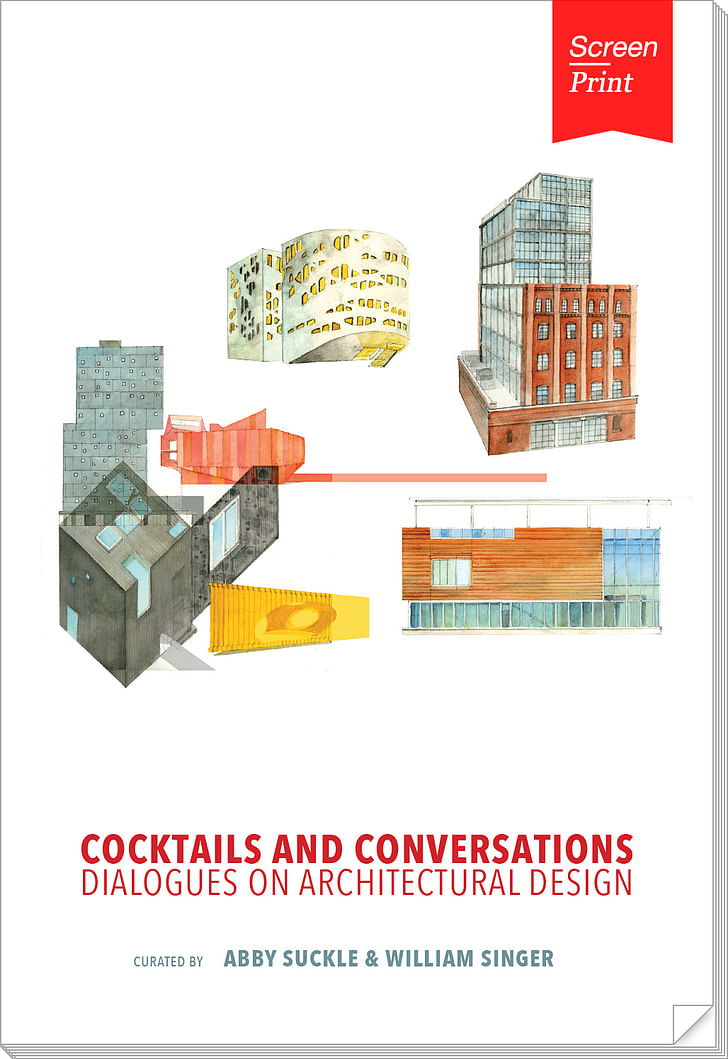

Screen/Print is an experiment in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

Do you run an architectural publication? If you’d like to submit a piece of writing to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.