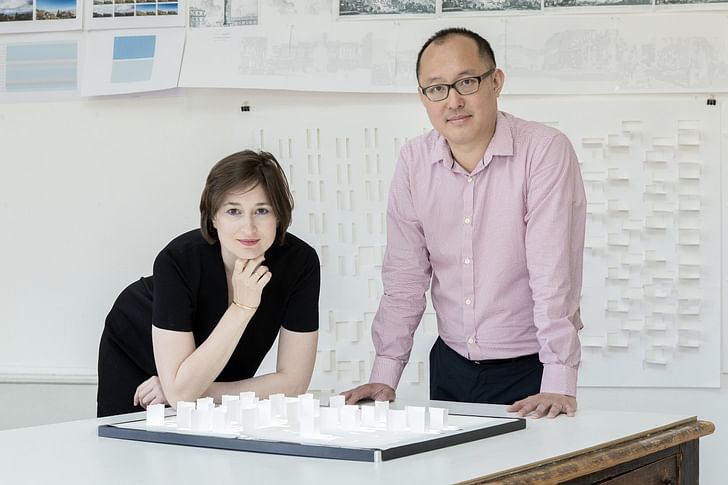

Every Monday we take a look at the ins-and-outs of growing a small architectural practice by highlighting stand-outs in the field. For this Small Studio Snapshot, we're talking with the winners of the 2016-2017 Founders Rome Prize in Architecture, Rachely Rotem and Phu Hoang. The duo, who run the New York-based practice MODU, discuss how the award has altered their practice, how to design for a rapidly changing environment, and how they are scaling across disciplines.

How many people were originally in your practice and how has receiving the Rome Prize changed your practice?

When we won the Founders Rome Prize in Architecture, we had five people in our studio. The experience of the Rome Prize has certainly changed our perspective on practice. We have been given the time and space to think about the kind of practice that we want to have, not only the practice that we do have. We are developing MODU to be more flexible and agile for the multiple roles design has in the built environment. Increasingly, our clients' projects demand the kind of engagement that refutes disciplinary boundaries in favor of more open design thinking.

As a cross-disciplinary design practice, we design for environmental and social adaptability at multiple scales in our urban, architecture, and interior projects. Our recent work at MODU has raised several questions. Can urban living refute the oppositional relationship between built and natural environments? Can architecture have more impact in strengthening the public realm and fostering communities? We are interested in the interrelationship of these two issues, which we approach with our ideas about thermal and social dynamics. In essence, the core question our practice asks is: can fewer borders between urban and interior spaces promote more sociable living in our cities?

How did you two meet and how did you decide to start working together?

We met in New York City, where the architecture community can seem both very large and quite small. One of the first projects we worked on together was a competition that we won. It was for a 25,000 square foot art park during the 2010 Art Basel Miami Beach fair. At the time, we each ran our own design practice and we collaborated together for the project. We continued this collaboration for several years—we quickly learned the advantages and disadvantages of being a solo practitioner versus being in a design partnership. After a couple of years of working in this overlapping way, we launched MODU in 2012—now five years later, we find ourselves asking "What next?"

Why were you originally motivated to start your own practice?

The motivations for starting a practice are multilayered—necessarily, since having a practice can be all-consuming! The impetuses also change over time, though there are some essential drivers that remain constant. We tend to thrive in a design process that involves 'deep dives' with our clients. Our best projects happen as a result of discussions that outline the clients' requirements; with this knowledge, we begin to uncover the hidden design opportunities driving the project. There are few aspects of practice more rewarding then seeing how these unexpected opportunities shape experiences at different scales—whether for the public in urban space, a group in the workplace, or within the domestic space of a home.

At the core of our design practice is the idea that designing for everyday experience can have an impact and change attitudes—especially about the relationships between architecture, people, and the environment. At the core of our design practice is the idea that designing for everyday experience can have an impact and change attitudes. This has always been a source of the concepts and cultural statement of our work. Our projects explore the architecture of weather, enabling weather—temperature, humidity, static electricity, etc.—as a medium to bring people into closer relationship with their environment. This closeness can be found in between exterior and interior spaces; in fact, we call them "weather rooms." The changeability of weather is an active agent in our designs, which encourage people to respond to its effects while also altering perceptions about the larger issue of climate change. In other words, we spend a lot of time talking about the weather!

What hurdles have you come across?

One of the daily hurdles we face has to do with the different speeds of running a design practice today. Of course, the fast-paced changes—social, cultural, and environmental—in our world often seem to run counterOften it seems like our discipline is not agile enough to address rapidly changing events to the slow deliberateness that is required for making architecture. Managing the difference of these two speeds can be challenging; often it seems like our discipline is not agile enough to address rapidly changing events. At MODU, we have adopted a strategy that allows us to work at multiple speeds: long-term, slower projects are combined with short-term, faster projects that enable use to work decisively and effectively. Incorporating speed into the organization of our practice has required us to be more adaptable to durations of time in our daily work.

Is scaling up a goal or would you like to maintain the size of your practice?

Our cross-disciplinary definition of practice, as well as size, is based on an integrated idea of growth. Instead of strategizing about "scaling up," we focus on a "scale across disciplines"—creating collaborations and partnerships with experts working in many arenas. MODU is founded on collaborative thinking and shared cultures that both broaden and enrich our design solutions. We have worked with scientists and artists, from a marine biologist to a robotics engineer and a music composer to an interactive artist, and continue to collaborate during our Rome Prize fellowship.

This is the "scale across disciplines" that we are interested in, one based on a breadth and depth of conversations with experts from other disciplines.

Part of our Rome Prize work is the opportunity to work with one of the architects from Renzo Piano's G124 group. The group was formed when he was appointed senator for life in the Italian parliament. He donated his senator's salary to form the G124 group, a multidisciplinary team that addresses important issues of the built environment. It has designed public spaces for the underserved suburbs of Italian cities, prototypes for the next generation of public schools, and, recently, seismic mitigation strategies after Italy's recent earthquakes. The group draws its members from a wide range of disciplines, including architects and planners, of course, but also sociologists and economists. This is the "scale across disciplines" that we are interested in, one based on a breadth and depth of conversations with experts from other disciplines.

What are the benefits of having your own practice? And staying small?

Both our research and our teaching are essential to our thinking about culture as a contemporary design practice that engages with social and environmental flux Perhaps one of the greatest benefits of running a design practice is that we can define what exactly we mean by 'practice'.Our cultural definition of practice involves a careful interplay between design and research. MODU is always focused on providing tangible design solutions for the built environment; we do so by mobilizing design as a form of research. This research spurs us to design architecture that engages people with the environment. By engaging practice with research, it prompts us to expand the boundaries of architectural discourse through conversations with scientists, artists, and social scientists. It certainly makes for engaging project discussions—and we take the opportunity to make friends who are not architects!

We are also interested in the idea that teaching is important for a critically engaged design practice. We both teach graduate designs studios in universities—Phu is at Columbia University's GSAPP and Rachely will teach at MIT—so we are able to bring the studio into the classroom, or vice versa, and create productive relationships between those two disparate places. Both our research and our teaching are essential to our thinking about culture as a contemporary design practice that engages with social and environmental flux.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.