Kate Schwennsen, Dean of Clemson University's School of Architecture, is hoping to strike that ideal balance between theory and practice that will prepare students to not only tackle the day-to-day challenges of working in architecture, but give them the inspiration to explore new conceptual territory.

In 2017, the School of Architecture at Clemson University in South Carolina will celebrate its 104th year of preparing students for a career in architecture. Founded in a spirit of regional pragmatism (combined with a love of Beaux Arts and Italian villa architecture), Clemson's program has expanded to Those big beautiful innovative theoretical ideas, we couldn’t survive withoutmultiple "fluid campuses," including locations in Charleston, SC; Genoa, IT; and Barcelona. Each campus offers students Clemson's signature pedagogical blend of theory and tried-and-true practice, paired with the particular practices of that region and country. So what's next for the school? Archinect spoke with Dean Kate Schwennsen about her philosophy toward deans being licensed, the integration into the school's curriculum of IPAL, and the importance of maintaining connections within the larger educational and governmental communities. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Briefly describe the school’s pedagogical stance on architecture education. How would you characterize the programming at Clemson?

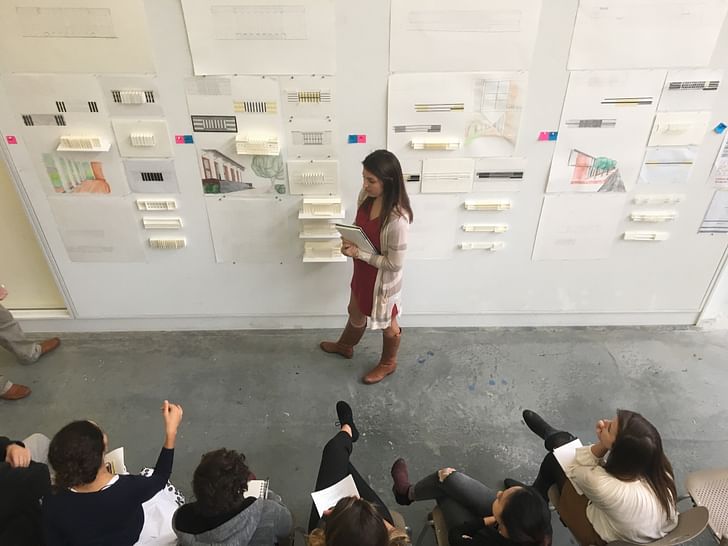

It’s hard for me to separate what I believe and what I think the school is, which I guess is a good thing. My pedagogical belief is in a school program that’s a balance between theory and practice, between speculation and application, between engagement and individual genius. I definitely think of constraints as opportunities and I think our program also views constraints as opportunities. Those big beautiful innovative theoretical ideas, we couldn’t survive without. That’s the quest, but I also believe in getting your hands dirty and for failing, and for providing a safe place to fail, because there is no other way to really deal with critical issues than to try something radical. I think we are dealing with critical issues and the architecture pedagogy needs to provide a means of doing that.

What kind of student do you think would flourish at Clemson and why?

Leadership is front and center in our mission and we think we prepare students for leadership by providing them with lots of choices and a variety of opportunities. They come together during some semesters and then they go off and do their thing in other semesters. To flourish at Clemson, it takes somebody who is self-motivated and who has a lot of curiosity and ambition. Somebody who relishes collaboration, somebody who will challenge their peers and their faculty and the discipline. We as a faculty like to say that students have a responsibility - their responsibility to us is to inspire us. So we want people who want to do interesting things in life and obviously make a difference.

What are the biggest challenges, academically and professionally, facing your students?

I think the biggest challenges are financial, both in school and after school. Architectural education is getting more and more expensive. I mean higher education is getting more and more expensive. And five years minimum, six, seven years, however long it takes an architecture student to get a professional degree, it’s a investment. I would say that’s it. Undergraduate nonresident tuition at Clemson is about $33000 a year, grad, while nonresident is $22,000 per year. They will get out and make $50000 a year. So it’s you know, it’s a challenge.

What are the things that Clemson does to help their students find employment after graduation?

We have three off campus locations. We are based in Clemson but we have a program in Charleston, a program in Genoa, and a program in Barcelona. We require all of our undergrads to spend at least one semester at our campus. We also require them to have a minor, and we require them to have two semesters of foreign language because we are trying to educate global citizens and leaders. The Charleston program, which is closing in on 30 years, has had an internship program for a long, long time. So students do internships in the morning and then classes are in the afternoons and evenings. We have built on that, one of the integrated past architecture licensure programs. We are one of the 18 schools selected by NCARB to have one of those programs. We are one of the 18 schools selected by NCARB to have one of those programsSo that student will be able to complete their education, their architectural experience program, and their examination prior to graduation in six years and a bunch of summers. So it’s going to take an extremely sort of focused student and it’s not for everybody. We are going to be careful in limiting enrollment as we start, but that’s one very definite criteria. So on our existing internship program, we are sort of expanding our ambition with that IPAL program. We also have a unique relationship with our state licensing board. They have paid the internship, now AXP fees, for our students for years. So they have an education fund that all registrants contribute to and then those fees help support our students registration fees for what was the IDP and is now AXP. I think there are a couple other states that do it now but I know South Carolina was the first. We have a career expo every spring. We get about 50 firms from all across the country and some of them are global firms. And our students show up for it. We’ve got a powerful global alumni network. So all those things help provide employment after graduation.

How do you familiarize yourself with trends within the architectural profession and academia, and adapt these observations into programming and student policy?

It’s such an important thing to do, to stay in touch. Our faculty and I are engaged with colleagues on editorial boards, professional service boards and others. As I mentioned when we began this interview, I was here in Washington, DC to chair the Latrobe prize jury. That’s certainly a way of staying in touch with sort of cutting edge push on research that is applied research that’s centered between academia and practice. I stay involved with the local AIA and attend. I am on the South Carolina Architecture Foundation Board, for instance, and I am member of the State Licensing Board. I co-chair the International Union of Architects Education Commission which keeps me very much in touch with global education –and architectural education issues. It’s fascinating and that’s just me. Many of our faculty are doing similar things. Students and faculty attend professional conferences. We’ve got an architecture and health program that’s almost 50 years old and every fall, the entire program, faculty and students attend the National Healthcare Design Conference. Most of our faculty have practiced or currently practice, particularly in our more urban campus locations. And then we have quite a few sponsored and/or industry engaged studios that bring industry and/or professionals into the classroom, which is terrific.

Do you have a method or process for deciding how to integrate what you see in practice into Academia?

Part of it is opportunistic, and part of it is based on leveraging existing expertise and existing reputation. So for instance, if I go back to our architecture and health program, we have a center for health facilities designed in testing with an endowed chair. She is the PI on a $4 million grant that’s looking at improving patient care through human centered design in the operating room. That’s certainly a practice issue, and our students are getting engaged with itThat’s certainly a practice issue, and our students are getting engaged with it. They just are completing building a mockup. Other programs wouldn’t have the expertise to do that. Other programs would have expertise we don’t have. We competed in the 2015 Solar Decathlon and our faculty and students came up with a very unique framing system that we applied for a patent for. We were able to leverage against some collaborations and research there. We have a Wood Utilization and Design Institute on campus, South Carolina’s big wood producer. So their system makes use of some wood technology that and we had connections there that again were unique to our situation.

Can you describe the relationship between Clemson, in all of its campuses, and the local governments that surround it and help form the student experience there?

In our Charleston program, every semester is engaged with locally based projects with either government or not for profit organizations doing things from a long term vision plan. They are these sort of big, urban design issues applied to sort of responding to the needs of a small not-for-profit. Half of the students are working on a design-build sort of public service projects when they are there and the other half are working on more urban design things which are usually associated with the government. In Genoa and Barcelona, I have been to reviews in Barcelona where the mayor’s assistant was present because the studio was looking at Brownfield sites and how to reach them for live/work sort of things. In Genoa, we often try to have public reviews and invite the local government but it’s a little bit more, it’s not quite so direct but they attend. We do a lot of speculation there about public space. So lots of engagement I would say.

How would you describe the relationship between architecture and the other departments at Clemson?

Landscape architecture and architecture have a whole bunch of collaborations from community design service learning studios to all of our what we call “fluent studios” or off campus locations. Landscape architecture students participate with architecture students. There’s multidisciplinary and vertical learning, which is wonderful. Our architecture and health program works a lot with our public health program, with our nursing program, and with the Medical University of South Carolina, which is in Charleston. We’ve got construction science and I was impressed by how articulate the students are and I think part of it is because of communications across the disciplinesmanagement in our building, which is amazing. Everybody knows that’s sort of an asset. So we’ve recently worked on an integrated project delivery certificate program proposal that’s a joint thing between architecture and CS and we look at it as something that will appeal to post professionals. We are just starting a resilient urban design program. That’s a collaboration between landscape architecture and architecture and city and regional planning. When I came to Clemson to interview almost seven years ago, I was impressed by how articulate the students are and I think part of it is because of communications across the disciplines. We have communications faculty teaching the required oral communications course to our first and second year students integrated with their design studio. They learn how to talk about what they are doing and I think it makes a huge difference. A communications faculty member will come to reviews and not talk about their work, but talk about how they are communicating about their work. It’s very useful.

Do you have a relationship with the advertising methods that Clemson uses, and if so, what is your approach to that?

Any advertising that we do, we as a school make those decisions about it and it comes out of our departmental operating budget. I am talking about architecture-specific advertising. Obviously, the university advertising is handled way above my pay grade and they do a very good job of that. They have a winning football team in the south. Certainly, we view our web page as our first frontline of advertising. Keeping that content rich and up to date is everybody’s great challenge. We do advertise with RConnect. We think it’s a robust place for us to be and we think we benefitted from that relationship. We advertise with AIAS. Again we think that’s a good place for us to be with NOMA, the National Organization of Minority Architects and of course through social media, Facebook and Twitter and all those things. We also still do one or two hard mailings a year to our alumni network and big firms and we think it still is good to get something physical in people’s hands.

How important do you think it is for the leader of an architecture school to either already have been or still to be a practicing architect?

For me it’s important because I can’t imagine anything else for myself. However, I have known some remarkable leaders of architecture programs who weren’t or aren’t licensed. Thomas Fisher at Minnesota comes to mind who, I am pretty sure, was never licensed, but he is a brilliant observer and participant in practice and thinking about future practice. So I think it just depends on the situation and the person and the collective wealth of the faculty. You have to think of a faculty as a collective that comes together and brings the unique expertise. It’s that collective that has all the wonder and covers all the breadth and depth. So if there is enough practice sort of focus from other faculty members, the leader may not need to be a practicing architect. I am sure I will have friends that will be concerned that I am saying this.

How would you like the school to have changed in your tenure?

I hope it’s more engaged outside of ourselves, more collaborative across campus and across disciplines, more expansive, more diverse and inclusive, and more engaged with a wider range of issues about which our students and faculty care about. It’s our discipline’s opportunity to engage from urban design to sustainable design, from materials research to operating room research to a wide variety of possibilities.

How do you teach students a code of ethics in architecture?

It has to somehow underpin all the work that students do so that when you ask questions during public conversations, they are invested in their responsibility to a greater good and I think we do that pretty well. We have a community research and design center that’s very engaged with public interest design. I would say it’s directed by very well respected faculty members and I think that starts to influence a lot of things. In those community-based projects you have to ask about the greater good when you are doing those things. We have an accreditation I don’t know where else you start in a professional practice course other than ethicsvisit this spring and prior to those visits, you have to update your learning culture policy and your studio culture policy. We got our students very engaged and thinking about and redrafting along with our faculty and in some ways, that’s sort of foundational code of ethics for a student body: how they see the public good of their community of students and students in faculty. That’s been an interesting thing to see and to participate in. We have a professional practice course that I teach, and I always start with ethics. I don’t know where else you start in a professional practice course other than ethics. Often, guest lecture series attach to some of our courses like they attach to the professional practice course. I will ask for my students to write just a very brief paper about, ‘What did the speaker have to say about architect’s role in advancing the public good?’ which is what I see as ethics. And then they remember that question every time they go to a guest lecture, I hope! Or I make them do it multiple times.

The Deans List is an interview series with the leaders of architecture schools, worldwide. The series profiles the school’s programming, as defined by the head honcho – giving an invaluable perspective into the institution’s unique curriculum, faculty and academic environment.

For this issue, we spoke with Kate Schwennsen, Dean of Clemson University's School of Architecture in Clemson, South Carolina.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

3 Comments

Genoa, Italy....not Geneva, Switzerland.

Corrected, thanks Marc.

I wonder what she would think of a new program emphasizing progressive traditional design they are proposing for the College of Charleston. It would be 'radical' to study and employ sustainable methods that people seem to love. One can only hope!

http://www.postandcourier.com/opinion/editorials/program-made-for-charleston/article_0d866dce-d1f8-11e6-92f7-a70dcb204bcd.html

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.