Since founding Aranda\Lasch in 2003, Benjamin Aranda and Chris Lasch have pursued their own uncompromising vision of architectural practice. Driven by computation and a fascination bordering on obsession with process, Aranda\Lasch has turned out some of the most exceptional architectural geometry on this side of Neil Denari.

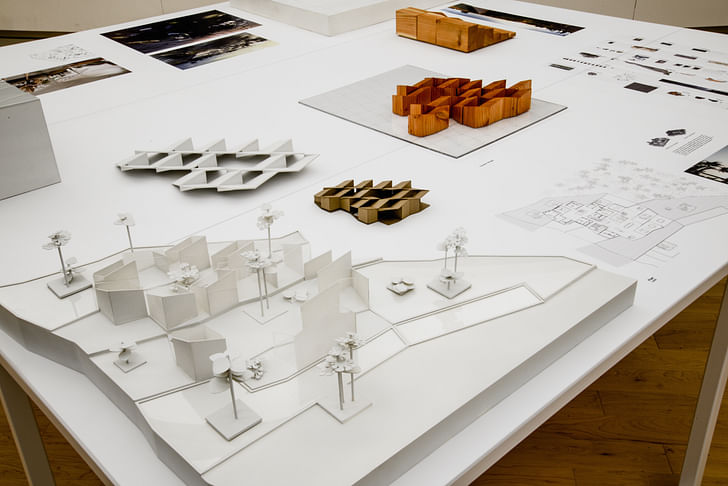

With offices in Manhattan and Tucson and projects on the boards around the world, they have cemented their place at the forefront of cutting edge architectural practice. After an early period of work on competitions, temporary projects, and high-end designed objects, they have since recently completed two buildings in Miami: the Art Deco Project (a retail space) and the Design District Event Space. In addition, two significant building projects are in process now: the Palais des Art in Libreville, Gabon and Budidesa, a residence and art park in Bali which is currently on exhibition as part of the Chicago Architectural Biennial.

I spoke with Benjamin Aranda, Chris Lasch, and Joaquin Bonifaz (a designer at Aranda/Lasch) at the Chicago Architecture Biennial about the changing output of their practice, making, computation, and participating in art and architecture exhibitions.

You met at Columbia [both graduated in 1999] – did you have a pre-existing interest in computation and process, or was it sparked by Tschumi and his paperless studio curriculum?

Benjamin Aranda: He brought in a faculty that was interested in computers. I don't think at that time it was necessarily about computation as we know it now. But after we graduated, we, as a mode of survival, worked outside of architecture. Chris worked at a search engine.

Chris Lasch: You worked at a search engine.

BA: Yeah, when you get old, the memories get hazy. I worked at a search engine.

CL: I worked at a multimedia mapping agency.

BA: I was working on search algorithms. Chris was working on...

CL: New forms of multimedia programming.

BA: When we came out of that, we started thinking about how we wanted to approach architecture. We looked at what we had learned and we had a new set of skills and a new approach – computation. That's when we started to produce projects like the [Color Shift] film, then small installations that started to use computation.

I learned how to letter. Never used that.CL: The facility with digital tools definitely happened in grad school. We were probably the last generation whose undergrad was totally drafting boards and ink on mylar. I learned how to letter. Never used that. After the paperless studio at Columbia, the profession hasn't really looked back except for one or two hiccups.

When you started your firm, some of your first projects were either installations or small built works. I'm interested in that dialogue between your design thinking and the actual making of the objects, which is clearly important to your work. How has that constant desire to be making shaped the trajectory of your career?

BA: That's an interesting question.

it was an absolutely terrifying and frantic phase of our lives where we were desperately trying to find any relevance and take any opportunity that came our way.CL: On the one hand, we were exercising our agency. [Benjamin laughs] We were a young firm starting out just a few years out of school. Didn't have a lot of experience or connections or projects. We sensed that it was important to build our voice. So we found ways to do that. The opportunities that are available to young architects are mostly the one's they can make themselves. These smaller, cheaper, self-initiated projects. We did competitions too. We went for grants and we initiated projects that we could do ourselves, totally of our own devices. We didn't want to wait for briefs.

BA: I think we were learning, too. There was a time between 2001 and 2005 when we really formed the practice. But there was about 4 years where we were just learning. Learning how to do things. [Chris] calls it an exercise in agency; I think it was an absolutely terrifying and frantic phase of our lives where we were desperately trying to find any relevance and take any opportunity that came our way. Actually it still sort of feels like that.

BA: Out of that came this sensibility to be critical of tools, to develop a methodology that the making of something was a deeply critical act. You had to question everything you were using at every moment in time. I think that led us to be very aware of how we were doing things. For instance, using any sort of procedural design tool, like computer code, was totally novel and it we like to learn from geometry, molecular structures. We like to see how that gets writ large.is not anymore. It's a way to problem-solve, but for us it was this new universe that opened up. We really wanted to get into it. We did. We are still about that, maybe stubbornly. I look at [the Chicago Architecture Biennial] and I think maybe we are being very dogmatic, but it's the ax that we are grinding. The reason is because we are interested in the worlds it opens up for us. We have always been interested in geometry and how to control it and make it meaningful. How it opens up concepts that are very deep and resonate with the sites and the people and the programs that we work with. What we were doing back then is very much behind what we do now. We use these things like geometry and systems and modularity and use them to have a conversation with our projects, and open the projects up to larger issues.

Before [starting the interview], we were talking about informality. If you go to [a lecture and roundtable held as part of the Chicago Architecture Biennial,] they will talk about informality and spontaneity and predictability. Does your process take the view that there are systems behind informality, they just need to be made visible?

BA: Absolutely. You know, we are always changing how we phrase this and talk about it. We do subscribe to this idea that the tools that we use allow us to make connections to very small things and very large things. That's why we like to learn from geometry, molecular structures. We like to see how that gets writ large. The issue with informality is that we are beyond the days where you could just draw a square and say anything can happen in there. You have to be very sophisticated as an architect to design that informality into a project. There are ways to do it.

There is an older article, not long after you started your practice, that paraphrases you saying that at Columbia you realized you wanted a system, or series of system, that allowed you to address each design problem in a procedural way. Have you found that these systems break down when you have to actually make the objects, especially projects at the scale of buildings? Does human intuition come into it?

CL: I think it is more relevant as we get to the bigger stuff. The stakes are higher, the pieces are bigger. The budgets are bigger. The procedures we need to engage with are more outside our control so the idea of having a logical approach doesn't mean that you We try not to have a style that is repeating what we saw or did. It is a way to familiarize yourself with your own evolution.institute a path towards an answer. It is just a way to organize your thinking, organize your actions in a way that you can open up new roads, new concepts, new inspirations. In that case, being more critical about what we are doing, making it more explicit is more crucial than ever. That's not to say that intuition isn't a part of it. The systems that we put in place train our intuitions with each project. That's what is exciting for us, keeps us interested and keeps each project fresh. We try not to have a style that is repeating what we saw or did. It is a way to familiarize yourself with your own evolution.

BA: Although I have heard people tell us that we do have a style. "I thought you guys were angles." I heard that from a very sophisticated curator. We have our predilections, but I think one thing – you get one career, you know? You get one lifetime to play this out.

CL: One lifetime, 21 projects.

BA: Yeah, you don't have a huge amount of time. Buildings take years. From the beginning of a building to the end of it, that trajectory is fascinating. I do think you need to make a commitment to your process and see how it plays out. That's probably one of the most difficult things to do, and that's what the last five years has been about it. Really committing to this approach and seeing what happens when it becomes buildings, rather than the smaller scale of work we were doing previously. Whether it works or not. And we are finding that it does work. We have a commitment to systems now more than ever because of the scale of architecture.

Could you talk a little bit about your process of identifying the design space when working at the building scale? On the smaller projects – the furniture and installation – it’s very clear that this is holistic design where every aspect has been customized by you. On the building scale, for example the Miami Design District Event Space, your design space is the face of the concrete slab. Or what immediately reads as Aranda\Lasch.

Joaquin Bonifaz: The more traditional architecture in the space – the area, the cores, the length of the cantilever, the structure – we worked on all that. But where we made the difference with our special set of tools was in the face of the slab, but that wasn't the only design we had to do. How the doors open, what the space would feel like.

BA: People are identifying the underside of the slab [as our work].

JB: The only thing they identify is the face of the slab.

BA: Most of the time on that project went into figuring out how to install a really expensive folding door that could open up and create a 45-foot long uninterrupted facade.

JB: The most identifiable part, the slab, was the easiest and the cheapest.

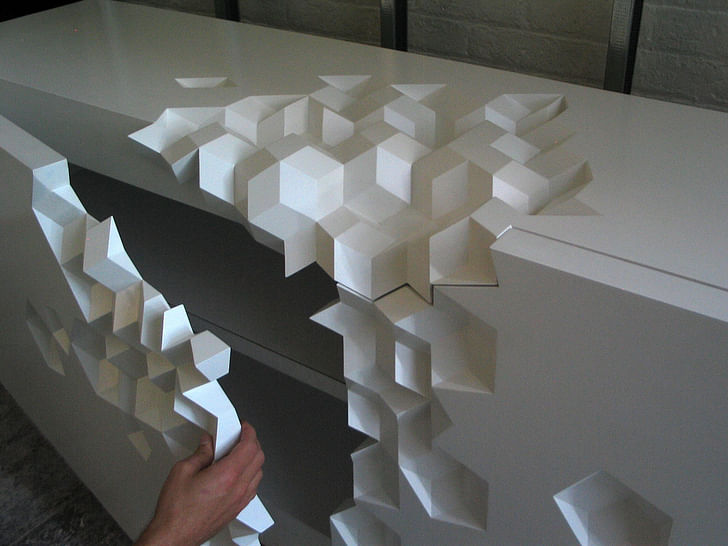

BA: Yeah, that slab. That's interesting that people identify just with that motif on the concrete slab. I don't think construction often decorates the underside of a slab you pour. That was one thing that a lot of our object making, our furniture making taught us. What we told the client was, "Seriously, pennies on the dollar, this is a negligible cost, but we can really make this sing." And they just said "Fine, do it.” And it is the identity of that project.

JB: Not only of the event space, but they developer uses it in billboards to advertise the whole neighborhood.

CL: That's why they wrote that contract like that. [all laugh]

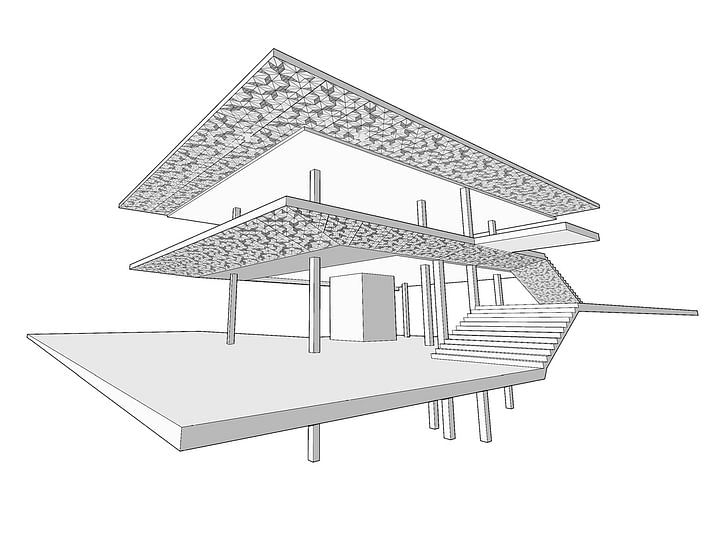

Then in the Art Deco Project, what is immediately identifiable as your unique process and sensibility expands a little more and becomes the entire facade with these unique tiled GFRC panels. Then on Palais des Art, the design space expands again and you get this even larger and more encompassing approach to the building that addresses structure, canopy – and even seating starts to read a continuous whole.

BA: I think what we're fundamentally interested in is how an extreme modularity can produce a continuity across a building that would allow it to have this singular reading. What ties those two projects together is a real obsession with reducing the components of a building down to one element. In the Art Deco Project, there was so much to that project – site conditions, building codes, tenant issues, there was all of that. On top of that, what we were interested in was developing that pleat. That idea of making a pleat as one singular reading allowed us to turn the vernacular of Art Deco into a system that we could enter and play with. That was the whole thing. We are really interested in exploring vernaculars. We are really interested in breaking them down into parts. If you do that, we can get in, we can make it our own.

The Palais des Art was the same thing. How do you develop a building component that can structure itself. And that became an aluminum extrusion that could spiral and stack and eventually produce this canopy. I think they are highly related.

In the way that Kahn would say, "Brick, what do you want to be?", it seems you look at materials and process in a holistic way and marry the two together. For example, in the Design Miami Event Space, that detail can only happen on the face of the concrete for such an economical price. Or on Palais des Arts, the hybrid structure and canopy is dependent on the aluminum extrusion. Could you talk about this idea of materiality and material properties?

CL: Yeah, that's interesting. We start with the abstract. We don't start with material, we don't have an ethic about using particular materials. We start more with a set of ideas that revolve around themselves and the place and the constraints of the project. We like to work with engineers and collaborators early on so that those ideas can find a material expression The clarity of the concept established early in the project lead to a very sympathetic and clear material research.in a pure way. On the Palais des Arts, we worked with AKT II engineers early on. The idea of turning the theater inside out, taking down the walls, required a canopy to shelter that space and tie together different parts of the project. So those ideas along with local constraints – having something that could be assembled off-site and finished simply and cheaply on-site by less skilled labor – initiated the solutions around the structure. So aluminum made the most sense for its light weight. The clarity of the concept established early in the project lead to a very sympathetic and clear material research. That material solution is always a process of discovery. We're not channeling the voices in the material, which I think Kahn was.

So it is a marriage of process and material?

CL: Yes. We are very interested in process, material, and also in the dialogue between digital and physical. And it took along time to learn through small prototypes and furniture. We learned early on how to go back and forth between the computer and the physical.

JB: One of the strengths of the modularity is its adaptability to different materials. We can make that switch very quickly because it is modular.

CL: With large, complex assemblies that are dependent on one another, it has ramifications downstream. With our [modular] process it is probably more efficient.

This modular approach is much different than that taken by someone like [Dame] Zaha Hadid or Sir Norman Foster, where each part is different and dependent on custom fabrication, but they still manage to create a cohesive whole.

BA: I think that seeing the world as a building up of discrete parts is not just a preference we have. We learned that because of the way that matter is organized and because of the way humans look at mathematics and geometry as a way to understand the universe. The idea of being discrete is our way to open up to larger movements. We were so inspired by the story of the quasicrystal. It literally was an obsession in our office for many years.

CL: It still is.

BA: It imbued into us a search for endlessness through parts. That search for endlessness can be seen in so many different ways in history. Not just as a molecule that organizes itself infinitely but also in the way that there are quasi-crystalline structures on the naves of mosques in Iran, show that human beings use the discrete to commune with the endless. We found this very inspiring. It’s not a polemic for us, it is something that really moves. It’s not about solving problems as much as it about opening up to these conversations with larger issues.

CL: It's also less expensive.

Nicholas Cecchi is an architect born in Denver and educated in New Orleans. Following completion of his degree, he worked briefly in single-family residential architecture before leading the design department of a Denver-based boutique architectural and sculptural design and fabrication studio for ...

6 Comments

Thank you for conducting such an insightful and rewarding interview, Nick. Your questions led to some really great content. I'll keep an eye out for your next piece.

Best,

TJ

BIG invented this a long time ago. I think we need to look to the future of architecture built by true geniuses of the field not academics.

It's interesting how architecture goes in and out of phases where pattern and geometry are considered interesting or important. There was a while in late modernism where groups like the Metabolists and the Structuralists used pattern as a way to generate space - but it kind of got subsumed by the idiosyncratic approaches of post-modernism, and left alone when the current starchitects (expressive modernists?) started. Except maybe Calatrava...

There is an admirable sense of play embodied in the statement "It’s not about solving problems as much as it about opening up to these conversations with larger issues" which distinguishes them from someone like Christopher Alexander who sees pattern as some fundamental requirement of good architecture. I'm eager to see what they come up with as they scale up in their work. And how it compares to the less-rigorous 'pattern space' being explored by some like Heatherwick and ...ahem... BIG.

"We try not to have a style that is repeating what we saw or did."

Of course!

Hi Chris, good to see you around. Excellent work. All the best.

18 x 32, I read the procedural geometry here as the identification of a particular approach or solution to a problem, the creation of rules governing the design, and the careful adherence to these rules (or alteration of them as needed) in order to produce the project.

Perhaps you are referring to procedural as in texture or displacement mapping, in which no, not every project is visually patterned, but at a deeper level they seem to be developed from a set of rules.... algorithms are just sets of instructions, they don't necessarily involve digital silicon computers.

This was a (rare) excellent Archinect discussion that touches on this topic:

http://archinect.com/forum/thread/141607095/parametric-details

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.