Lina Bo Bardi: Together is not, and does not attempt to be, the definitive collection of Lina Bo Bardi’s work, but rather an examination of her life, influences, and motivations for producing her timeless architecture and enduring contributions to Brazilian, particularly Bahian, culture.

The show’s installation at the Graham Foundation, set to run through July 25th, marks its North American debut. Together is curated by Noemí Blager, with contributions by a skilled group of architects, artists, and filmmakers. Together strives to telegraph, at great spatial and temporal distance, the conditions within which Bo Bardi practiced and the metropolitan and rural cultures from which she drew inspiration.

Lina Bo Bardi was born Achillina Bo in 1914 and attended Rome University College of Architecture, graduating in 1939. She worked for a time in Milan, and collaborated with many of the leading Italian architects of the time. In the aftermath of World War II, she toured the country in order to document local destruction and rebuilding efforts. This, as well as her participation in the First National Meeting for Reconstruction in Milan, contributed to the anti-fascist, populist politics she would carry with her through the remainder of her life. In 1946, she abruptly moved to Rome and married Pietro Maria Bardi, an art dealer, critic, and journalist. They departed for Rio de Janeiro later that year seeking new markets for the art that Pietro Maria Bardi dealt.

It is here that Together picks up Bo Bardi’s story, with Ioana Marinescu’s photographs of her Casa de Vidro (Glass House), the first built work Bo Bardi realized. Completed in 1951 on the outskirts of Sao Paulo, the house was designed and built for herself and Pietro Maria Bardi. The house shows the first stirrings of Bo Bardi’s mature style and process in its deference to the site, including a spacious courtyard wrapped around trees and foliage. But the architecture remains heavily rationalist and indebted to the international style of modernism that flourished at the time. The exhibition displays the photographs on simple steel and concrete stands, designed and fabricated by London-based Assemble, subtly referencing a set of exhibition displays Bo Bardi designed for the Museum of Art Sao Paulo during the same period. These subtle referential features and clues run throughout Together, providing tools and hints for the viewer who chooses to dig deeper, while not attempting a complete catalog of Bo Bardi’s life or work. Blager said of the curatorial and artistic approach, “What we wanted to show with this exhibition is her approach. The things that matter to her, that gave her [work] importance, that influenced and informed her processes and methods.” This narrow focus wisely limits Together to investigating the conditions and experiences that helped shape Bo Bardi’s mature approach to architecture."Her buildings are totally timeless because what matters is not the container, but the content. To her, architecture was program… Her architecture completes when it is inhabited.” - Noemi Blager

The exhibition’s atmosphere shifts as it moves into the following room. Films by Tapio Snellman are presented on small screens recessed into an Assemble-designed console, showing street life and atmosphere in Sao Paulo. The content and craft of the films, and their presentation inside the concrete console, lends a sort of depth and otherness to the images, which transcend time and space to set the scene for what is to come, both in the exhibition and in Bo Bardi’s career. Within the darkened space, dramatically lit cabinets filled with found-art pieces (by Dutch artist and OMA co-founder Madelon Vriesendorp) provide context for the transformation that was taking place in Bo Bardi’s life as she acclimated to Sao Paulo, and ventured elsewhere to the Brazilian state of Bahia. The cabinets are constructed of the same concrete as the console. These objects are the product of a workshop run by Vriesendorp in Salvador de Bahia, Brazil in collaboration with Brazilian craftspeople. It was in Bahia that Bo Bardi truly connected with Brazilian culture and the privation and social inequality which would drive her architecture (and activism) through the remainder of her career. These artifacts are found in every room of the exhibition, lending continuity and providing a physical manifestation of the Brazilian spirit and culture which so affected Bo Bardi. The methods Vriesendorp engages, while collecting and assembling these objects, references the physical and intellectual bricolage Bo Bardi employed throughout her life.

Projection screens fill the next space, inverting the dialogue between image and object in the previous room: film is set in the foreground, while the iteration of found and constructed objects take on the supporting role. The films investigate Bo Bardi’s masterwork, the SESC Pompéia, a disused factory in Sao Paulo which she converted to a multi-use leisure center, completed in 1986. It is here that her architecture found full and complete expression in the creation of spatial scenarios, a complete focus on program which allowed form to follow the needs of inhabitants. The project combines sporting, recreation, meeting, shopping, and medical facilities, addressing each program as an independent scenario without hierarchy or privilege.

It is [in the SESC Pompéia] that her architecture found full and complete expression in the creation of spatial scenariosThe architecture of SESC Pompéia contrasts strongly with that of her earlier projects. While this and prior works stem from the same Modernist tradition, each express the values of the modern movement differently . Bo Bardi’s early work, represented here by Glass House, conveys the definitive formal values of mid-century Italian modernism through rigorous detailing and structural rationalism. Her later work, embodied in SESC Pompéia, diverges from this approach by forgoing aesthetic and structural rationalism in favor of the the social and political values the modern movement represented. Tapio Snellman captures in his films the activity and life of this building – which is then juxtaposed by Ioana Marinscu's still images of the Glass House, absent of inhabitants. Snellman’s films, along with the cultural artifacts Vriesendorp presents, allow a complete reading not of the inanimate architecture or space, but of the activation of space; of what these buildings meant once animated by inhabitants.

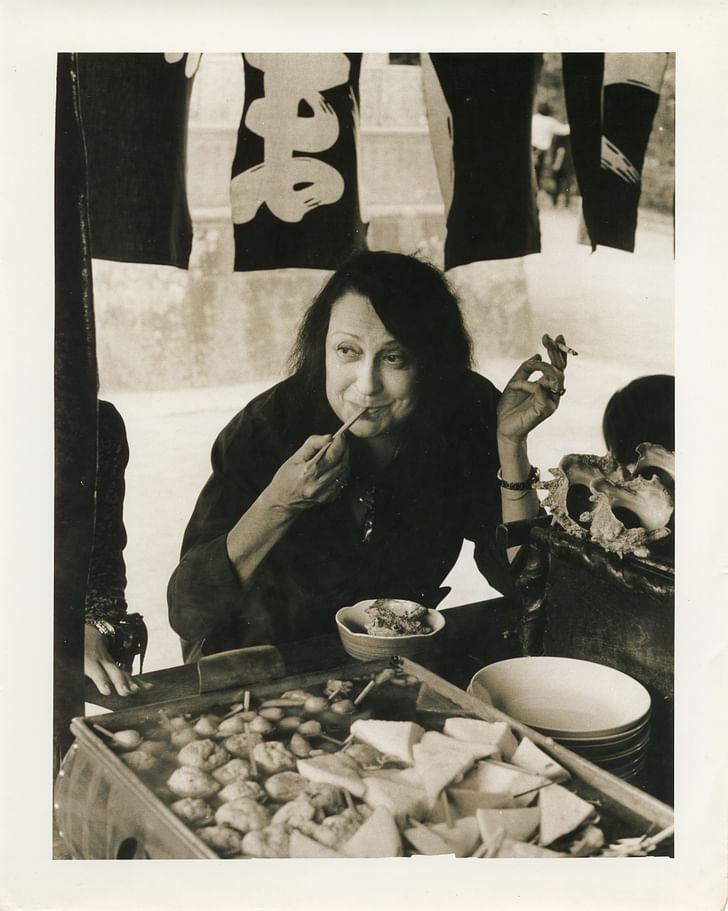

Bo Bardi’s work and life resist reduction and compartmentalization into terms easily digested. To experience and understand Together is to experience the sum of conflicting experiences, opinions, and buildings Bo Bardi brought into this world. A figure seen throughout the show, the Eshu, or Exú, is a mythological trickster figure found in many African and Caribbean cultures, and particularly resonant in Bahia. As presented, the Eshu take on political and symbolic significance, representing Bo Bardi’s multiplicitous positions throughout her life. She was educated in a culture of pure formalism and rationalism, yet her work found full expression when she approached architecture as a series of programmatic scenarios, where form was secondary. Bo Bardi belonged to the elite of Brazilian and Italian society – her marriage to Pietro Maria Bardi, an art dealer, placed her firmly among the privileged, a station which she repeatedly rejected. Bo Bardi found peace and expression in Bahian craft and the Eshu take on political and symbolic significance, representing Bo Bardi’s multiplicitous positions throughout her life.culture, elevating handcrafts and functional constructions to the prominence of the Western tradition she had been inculcated into in Italy. Lina Bo Bardi transcended time and place, as many of those who move between cultures do. While her work did not have the same immediate impact as the formalist manifestation of modernism (her first built work, Casa de Vidro, was completed the same year as the Farnsworth House), her vision – inclusive, democratic, driven by program – has proven to be the more durable approach to architecture.

Like Bo Bardi’s life and work, Together resists easy compartmentalization. Elements of it may be seen as reductivist or revisionist, but it never sets out to tell the entire story. The exhibition is beautiful, and beautifully executed – a journey through the life of Bo Bardi and her adopted culture. Together should be taken as a beginning, not an end, for a younger generation of architects who may not be familiar with her work, but would find her ideas and architectural expression imminently applicable to contemporary practice.

Together runs through July 25, 2015 at the Graham Foundation's Madlener House in Chicago.

The exhibition is sponsored by Arper, a furniture design company based in Treviso, Italy, that also collaborated with Instituto Lina Bo e P. M. Bardi in São Paulo to produce a limited edition of Bardi's Bowl Chair (1951), in celebration of the centennial of Bo Bardi's birth.

Nicholas Cecchi is an architect born in Denver and educated in New Orleans. Following completion of his degree, he worked briefly in single-family residential architecture before leading the design department of a Denver-based boutique architectural and sculptural design and fabrication studio for ...

2 Comments

that drawing of chairs is beautiful!

I love her work. It's rugged and big without being standoffish. Knew nothing about her background - interesting.

Like wise. I had never heard of her until I saw her on architect. I love her range of work.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.