What can an architectural publication accomplish in a five year lifespan? Can it deliver on its promises and produce something of value, while holding itself accountable throughout? This is the self-imposed challenge of SAN ROCCO, an architecture magazine based in Milan, Italy. The magazine began implementing this “Five-year Plan” in summer of 2010 with its appropriately titled first release, Innocence, and is now in its eighth issue, with plans to release no more than twenty in total.

The name "San Rocco" refers to the site in Monza, Italy of an early competition project by Aldo Rossi and Giorgio Grassi, proposed in 1971 and never built. Little evidence of the architects’ future renown shows up in the briefs, and as a result the project was largely underrepresented in historical discussions -- an imbalanced, unstable hybrid of two architects. While it may not be the obvious origin point of two notable careers, San Rocco represents nonetheless the beginning of something different in architecture, a newness whose inconsistency only makes the architects' later projects more remarkable.

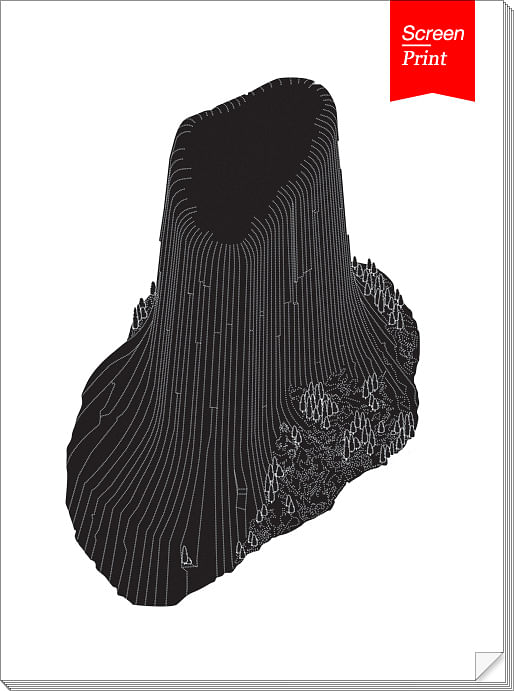

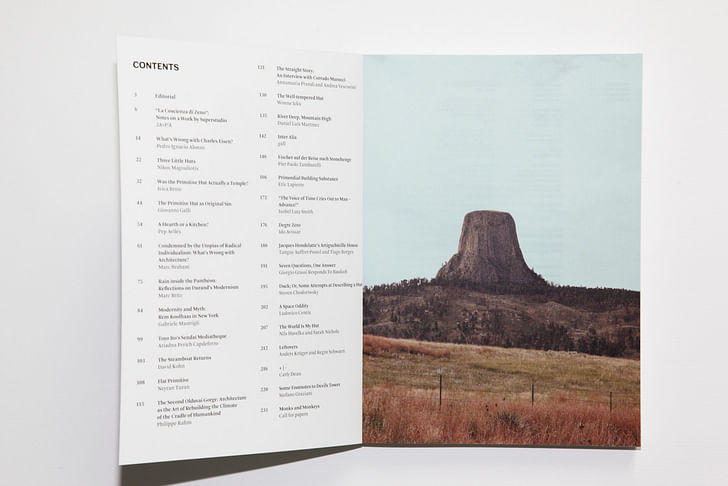

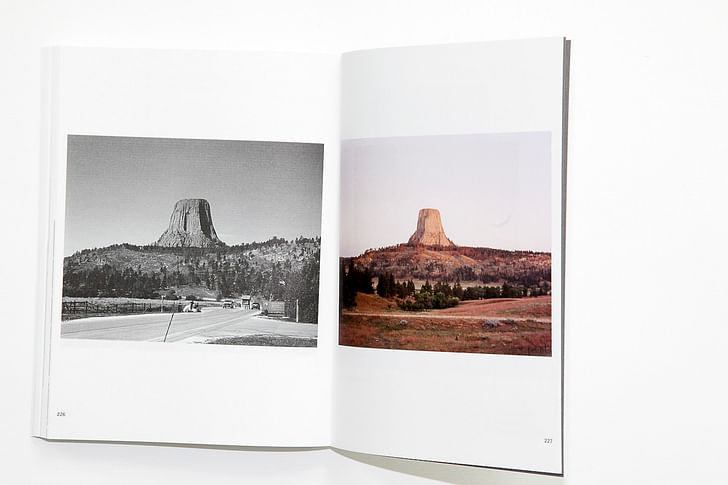

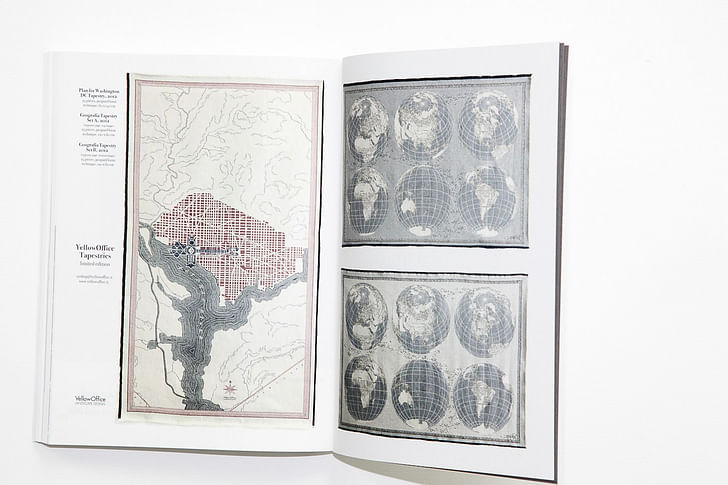

In the spirit of that uncharted progression, the editors of SAN ROCCO are pursuing new forms of architecture writing and scholarship. Calling the magazine both “serious” and “neither serious nor friendly”, and then “not useful” nor “particularly intelligent”, the editors approach architectural discourse’s self-seriousness with a constructive irreverence. We’re featuring SAN ROCCO’s eighth issue, What’s Wrong with the Primitive Hut? (you can learn a bit more about that concept here), with a piece by architectural office 2A+P/A on Superstudio’s “La conscienza di Zeno”.

“La coscienza di Zeno”: Notes on a Work by Superstudio

by 2A+P/A

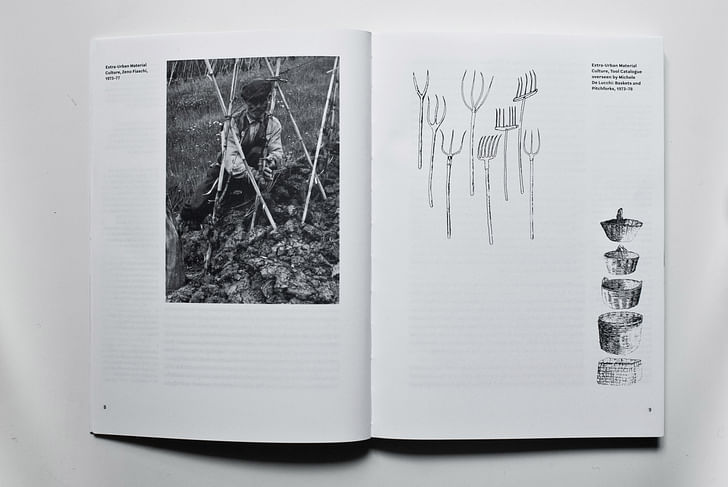

Superstudio’s project “Zeno’s Conscience” (aka "Confessions of Zeno") was an anthropological investigation of the life of Tuscan farmer Zeno Fiaschi that was part of a more extensive study called “Extra-Urban Material Culture” presented at the Venice Biennale in 1978.

Superstudio carried out this research project during their time as teachers at the University of Florence from 1973 to 1978. Based on the analysis of the relationship between the form and function of everyday objects, they developed a set of tools for interpreting the behaviour and basic needs of the individual.

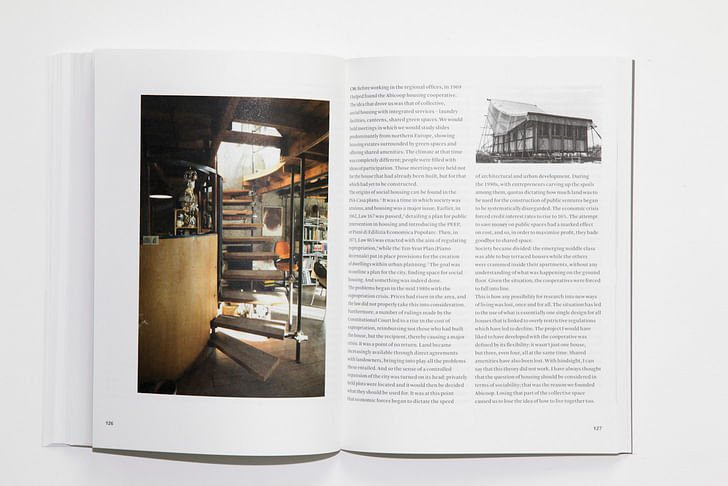

Zeno Fiaschi was a farmer of the Maremma region born in 1903 in Riparbella, a small village in the province of Pisa. He lived all his life in the same house, one his grandfather had built years before, when the family had grown.

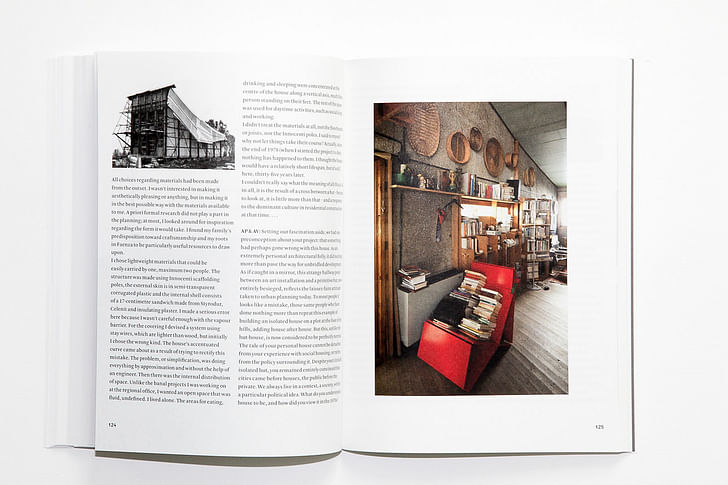

Alessandro Poli had met him after buying a house close to his as a summer residence. Superstudio’s interest in the life of Zeno was not limited to understanding the dynamics of rural activities through his experiences; it also extended to his specific ability to live in a totally self-sufficient way. Zeno lived only by means of his own manual labour. He only used things that he could repair or build by himself, employing materials available in the same environment in which he lived. All items in his possession, no matter how damaged by wear and tear, were constantly being repaired. Zeno made all the tools he needed with his own two hands.

Superstudio’s survey of Zeno’s life was about not just observing Zeno’s living conditions, but also highlighting his abilities, his consciousness, how he dealt with his surroundings – and in the end, his sensibility, the way he feels. For Superstudio, Zeno represented the Zeno lived only by means of his own manual labour. He only used things that he could repair or build by himself, employing materials available in the same environment in which he lived. possibility of living in total autonomy. Through an analysis of his life, they tried to build a survival guide, a grammar of a culture of self-sufficiency based on the techniques of reusing and recycling.

Superstudio’s research ultimately concluded with the declaration that “the only true art is our life”.

As Poli later described it, “Zeno’s objects and utensils were paradoxes he had built for actual use and not for display . . . that arise from an entirely self-managed relationship between the individual, society and the environment” (Poli, Other Space Odysseys).

In the attempt to overcome the perception of design as a simple exercise of “evasion” (see “Design d’invenzione e design d’evasione”, Domus 475), that was only marginally capable of influencing our behaviour, and in the belief that architectural design could change the world, Superstudio shifted the scope of their investigation, stating that “cultural anthropology, research on humans and their mental and material production, [and] attempts to consciously change the environment and ourselves are all part of a process of lifelong learning that involves us completely” (Natalini, SpazioArte 10-11, 8).

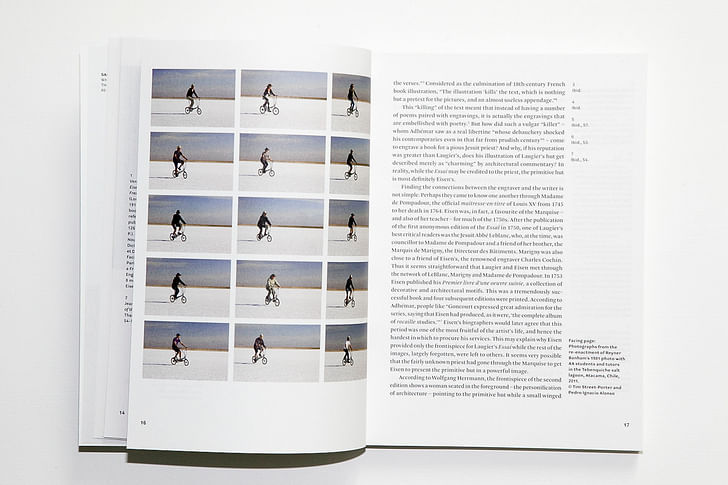

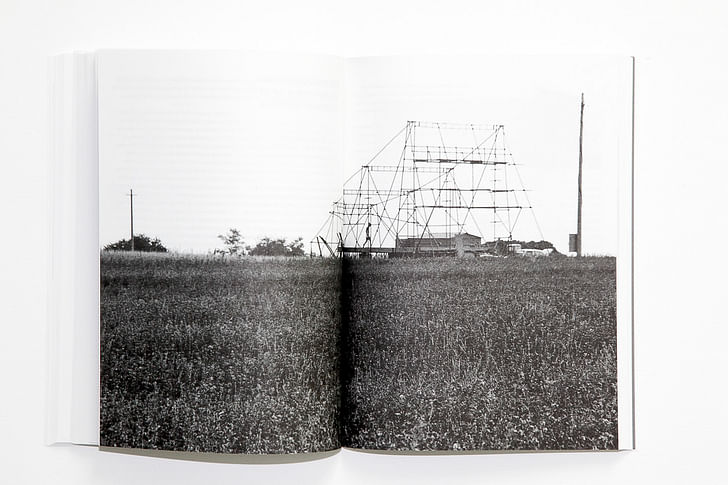

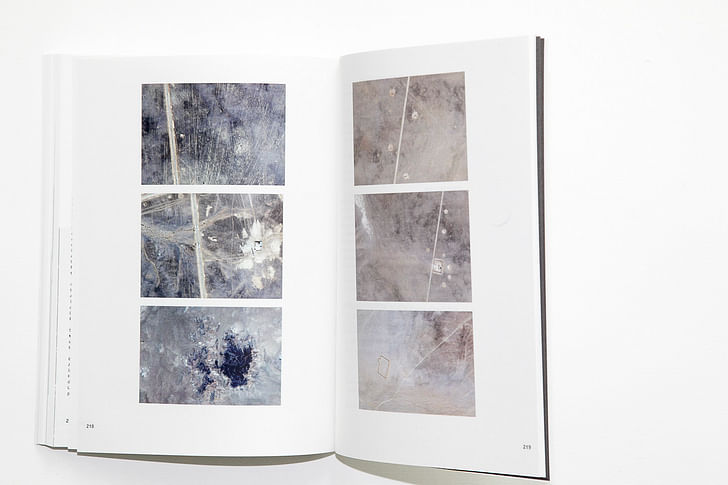

The work on Zeno consists of a system of maps describing the relations his family had with the plot of land they inhabited, and those between different spaces and moments of everyday life. Schemes were produced to monitor and track Zeno’s daily movement across his different properties, which were called preselle. An accurate analysis of his residential and work spaces was recorded by way of surveys that recorded how specific functions were carried out in those places. Many photographs and measurements of the tools that Zeno used in daily life were collected together with all those inventions that he had achieved through a process of the constant re-use of components and materials.

Superstudio described the information they collected as follows: “The sequences of photographs, images and objects document [Zeno’s] relationship with the world, and at the same time they are our attempt to rebuild a sense of design processes and uses that has been lost in our culture, but that still remains as an anthropological document in marginal areas of our society" (Pettena, 95).Zeno represented the possibility of living in total autonomy.

In 1973 Adolfo Natalini, then Professor Leonardo Savioli’s assistant, had been instructed to instruct the course on “Plastica ornamentale” that was an elective in the programme of study focusing on three-dimensional decoration and its applications. Natalini invited his colleagues from Superstudio to participate in the course: Gian Piero Frassinelli, Alessandro Poli and Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, along with Michele De Lucchi and Lorenzo Netti. The initial task was to conduct an analysis of the project, an exploration of “all those materials whose form has the sole ideological aim of being useful in our lives” (Natalini, Poli, Toraldo di Francia, 52).

They gave lectures on common objects or instruments, comparing them to each other to see similarities or differences in the way they were used and designed: “our work in the university is to analyze the design (its motivations, its management and its relationship with society and the environment), searching for alternative uses. We use simple, everyday objects, self-managed processes (such as agriculture and crafts) and extra-urban material cultures as areas of inquiry” (Pettena, 95).

The different courses that followed had titles like “The Motivation of Architecture”, “The Galaxy of Objects” and “Simple Objects of Use”. As time passed, various other elements started to accrue to these first experiences and these would later give final form to the research on Extra-Urban Material Culture.

This is how Natalini has recalled the beginning of the experience:

"In 1973–1974 we thought we would dedicate ourselves to a type of work with the students of the University of Florence. With Alessandro Poli a research on the suburban material cultures started. We were interested in simple objects of use, farm tools, crafts and buildings without architects: we were seeking the roots of creativity. This investigation led us to fieldwork – first throughout Italy, and then in other countries, such as Greece – through We were interested in simple objects of use, farm tools, crafts and buildings without architects: we were seeking the roots of creativity.which we were trying to see how the same tool was altered from place to place according to [the] availability [of materials]. In my lessons at the University, I used simple, everyday objects – for example, canes, chairs, knives and pots: I brought them into the classroom to show how they work and why they were made that way" (Biraghi et al., 248).

According to Superstudio it was time to perform the “technical destruction of the object” (Superstudio, Argomenti e immagini di design) in an attempt to free man from a culture that limited and conditioned his judgement and freedom of action. This was made possible only by imagining removing the distinction between producer and consumer: “simple objects are examined as a kit for survival: through critical inventories, reductive design, craftsmanship and use, we try to understand their deeper structure. As mediators between us and the world, objects turn into a mental catalyst for processes of self-analysis that constitute a liberating therapy” (Pettena, 95).

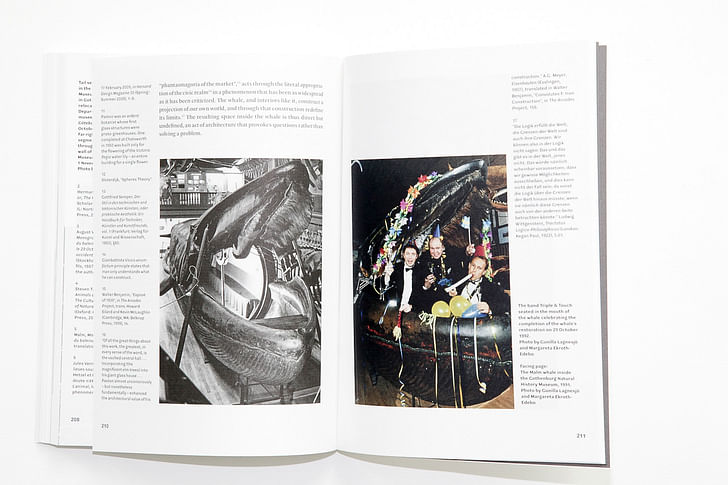

This is the period in which the Global Tools experience begins. After the famous exhibition in New York entitled Italy: The New Domestic Landscape and the 15th Triennale di Milano, it had raised the issue of giving continuity to the radical movement, which was mostly made up of mavericks, and establishing lines of cultural policy to create a network between the various experiences. The Global Tools investigation launched an open school that, through a series of workshops, was intended to give continuity to the movement, widening its field of action. Superstudio participated very actively in this collective experience, but it would last only a year, from 1973 to 1974. There is little documentation of their work, such as a declaration outlining the founding goals of the project.

Superstudio’s exploration of extra-urban material culture involved discussing precisely the they tried to identify the fundamentals of design in a popular culture that had existed before the social changes brought about by industrialization.same topics investigated in the Global Tools project, but it transformed the latter’s interest in the primordial forms of architecture into the possibility for developing an anthropological investigation whose aim was the re-definition of the discipline of architecture.

On the one hand, Superstudio seems to have affirmed the value of a shared knowledge of architecture, which they interpret as a collective experience. On the other hand, they also strongly critiqued the cultural system of design, which was increasingly oriented toward consumer use of object, a fact which negated any aspiration to create and put the user-designer in a subordinate position in relation to the manufacturer.

In contrast, Superstudio’s goal was to recover a sense of the common good: “Design now offers a reality that more and more takes the form of a value of exchange, which hides and progressively destroys its value in terms of its use in a continuous replacement of the real with the fictitious. Through the study of material culture, we are trying to reverse this trend in order to recover the creative and collective aspects of design” (di Francia, Natalini, and Poli, 52).

With the aim of moving away from a kind of cultural market, they tried to identify the fundamentals of design in a popular culture that had existed before the social changes brought about by industrialization. In an attempt to react against a renewed bourgeois cultural hegemony, the model of the farmer’s world offered a strategy for working against a sort of ideological restoration of the disciplines of architecture and design.

The search for a deeper, primordial sense of the design project led Superstudio’s investigation to carry out a close analysis of the relationships between objects and their uses, as well as the spatial organization of the land. Natalini, Poli and Toraldo di Francia were “interested in highlighting the primary aspect of design through agricultural tools, which, from the hoe to the form of the territory, are each characterized by their respective use value, and . . . each transformation is accomplished through a comprehensive understanding of the reality on which one is operating” (di Francia, Natalini, and Poli, 51).

The absoluteness of the meaning of these popular, rural references was the prerequisite for the establishment of a new ideological approach whereby the relationship between urban centre and countryside could be subverted in order to imagine a different model of development based on real needs rather than on the commodification of desire.

In the catalogue of an exhibition held at the Istituto Nazionale di Architettura in Rome in March 1978, Superstudio wrote:

In the analysis of marginalized or subaltern cultures you will discover the mechanisms of survival that, beyond the system’s patterns of development, preside over the transformations effected. It is in this huge wealth of knowledge that we can trace not only the roots of our science, but also the possibility of a different one. By referring to this context, we can properly analyze the direct relationship between man and nature, between man and his ability to create functional value – in short, between man and the objects he employs to meet his real needs – by using knowledge, intelligence and creativity, all of which the system of the division of labour has rendered unnecessary in the production of goods (In-arch, Istituto nazionale di architettura: Roma, Palazzo Taverna, 20-23).

Superstudio’s exploration of Zeno and extra-urban material culture represents an extreme attempt to verify the existence of a common culture with the aim of seeking out the foundational elements of a shared culture.

More about SAN ROCCO:

Editor

Editorial board

SAN ROCCO is an idea and promoted by:

2A+P/A, baukuh, Stefano Graziani, office kgdvs, pupilla grafik, Salottobuono,Giovanna Silva.

Screen/Print is an experiment in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

For this issue, we featured SAN ROCCO's What's Wrong with the Primitive Hut?

Do you run an architectural publication? If you’d like to submit a piece of writing to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

2 Comments

great synopsis -

I'm not sure why this magazine hasn't been on my radar.

Really good. Reading was triggered by today's Screen Print with Greg Lynn's Future Primitives.

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.