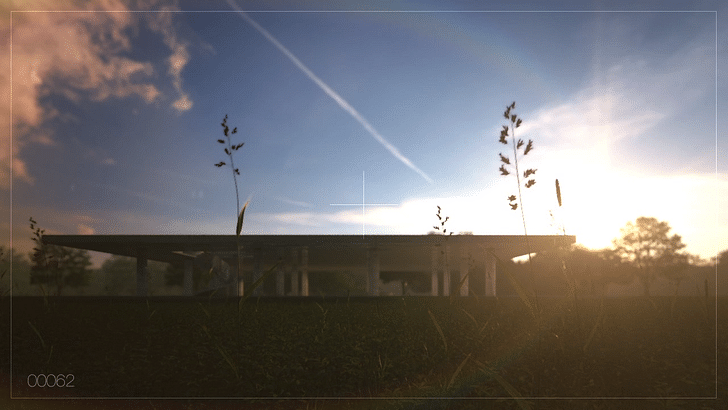

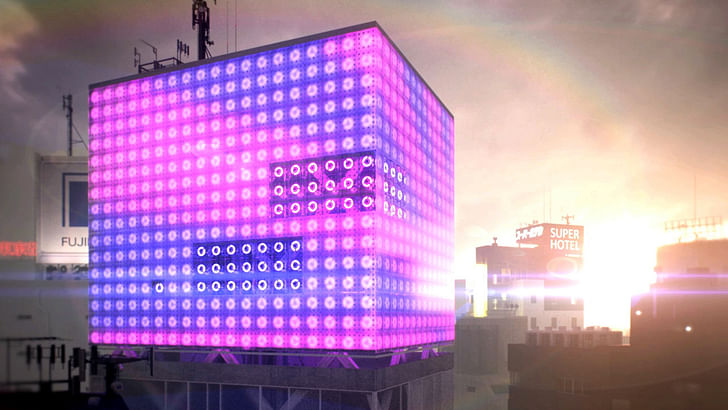

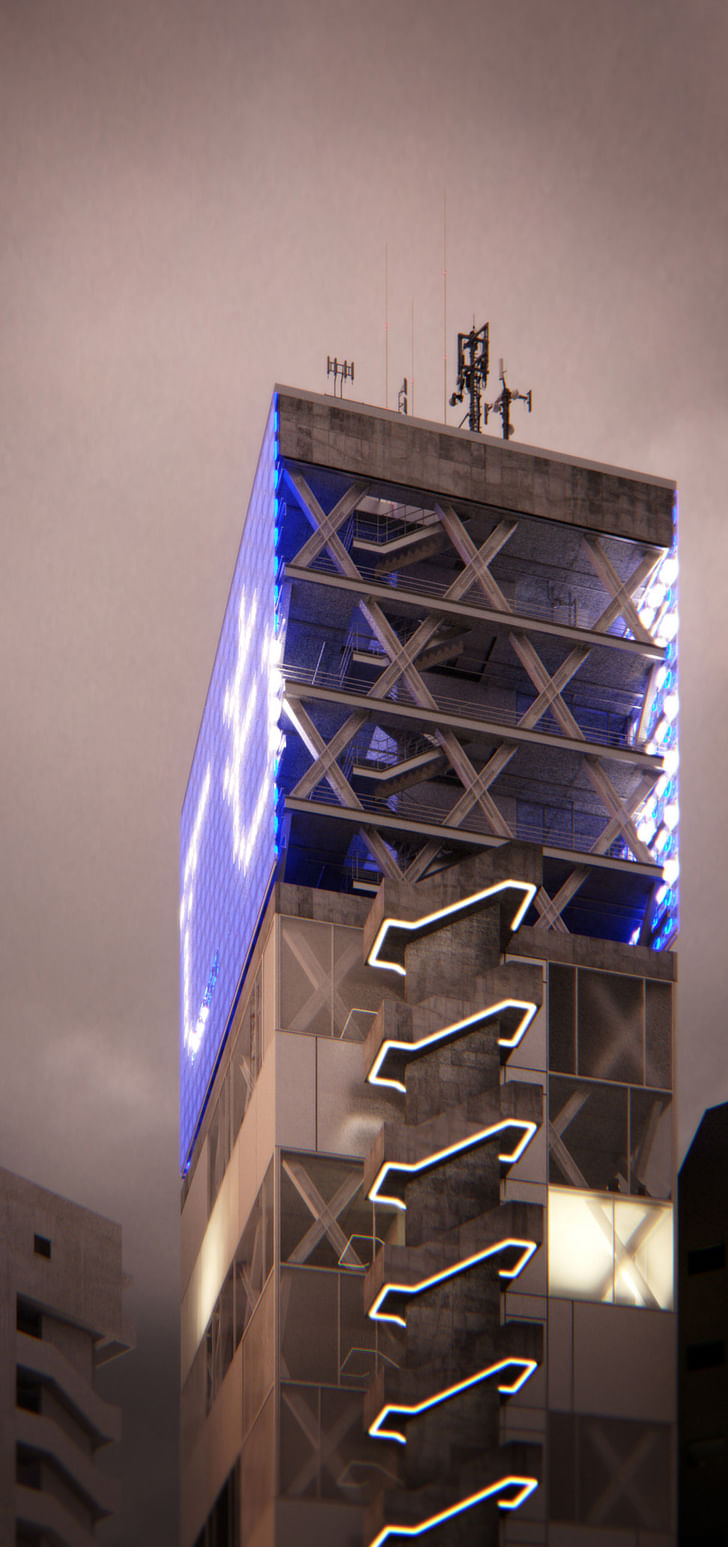

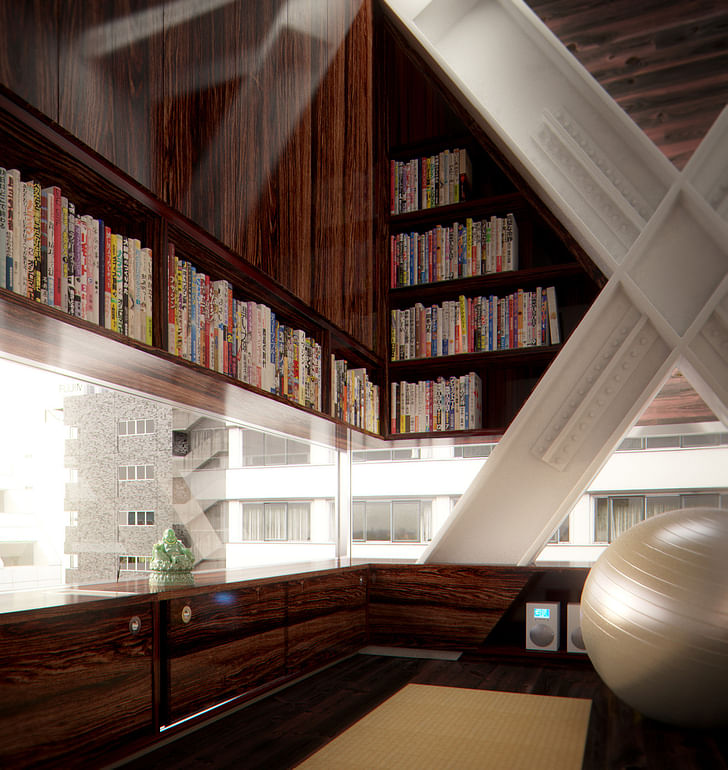

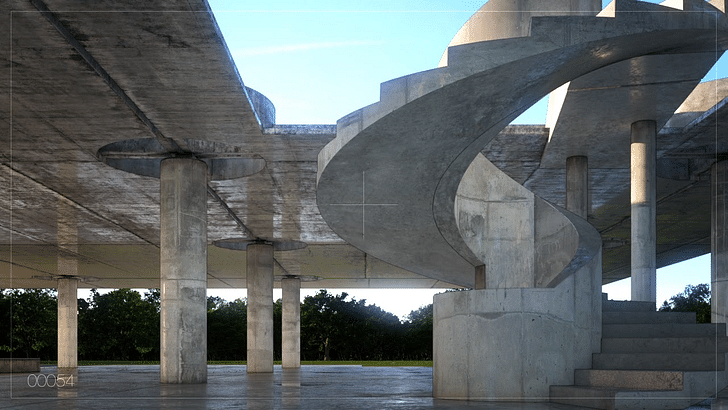

Architecture and the Unspeakable is a triptych of short, magnificently animated films, each exploring a different symptom of architecture’s vulnerabilities. Produced by Brooklyn Digital Foundry and directed by architect John Szot, the films feature architecture proposals from John Szot Studio, imagining distinct fictional buildings in New York, Tokyo, and Detroit -- all animated in striking digital realities.

The animations have little in common with slick digital renderings, and manage to overstep any uncanny valleys by creating a humming, spirited atmosphere that seems invigorated by a human presence without ever showing one. There is no strict narrative, but each film is highly suggestive of lives lived and time passing through these structures.

The third film, on Detroit, will premiere as part of MAS CONTEXT's Spring lecture series, at the Logan Share in Chicago on April 8th. You can watch the New York and Tokyo films below.

In anticipation of the premiere of the final film, Szot answered a few of our questions about the AAU series via email.

Amelia Taylor-Hochberg: Before I ask specifically about Architecture and the Unspeakable, your website describes your studio as focusing on “the relationship between technology and the locus of meaning in the built environment”. Could you explain what you mean by the “locus of meaning”?

John Szot: We're talking about the level at which meaning resides in the buildings we create, or even more directly, what makes a building meaningful. The word “locus” is a reflection of the fact that buildings are complex entities interpreted at multiple levels. It also allows us to avoid digressions since words of similar meaning like “site” and “place” already play specific roles within an architectural enterprise, and metaphors make articulating oneself needlessly difficult. Pinpointing the “locus of meaning” in buildings is one of the central ambitions of our work; one which we hope will change the course of architecture’s critical history to include all the richness that comes with making, contemplating, and using buildings under all circumstances. So far, this has meant looking beyond the technical perfection and material innovation that is commonly billed as architectural achievement and embracing the organic nature of buildings. We believe this is the only way to fully understand architecture’s creative essence, which we refer to as “buildingness” - a term we find apropos for its solipsistic opacity.

What drew you to Soho, Tokyo, and Detroit specifically to use in the AAU projects?

Generally speaking, we sought a context for each project that would complement and support the idea behind that project. This was important because we knew from the outset the ideas themselves were highly vulnerable to dismissal on practical grounds. Working within a context presented the opportunity to engage a specific cultural precedent. This in turn laid the foundation for a larger dialog that could transcend practical skepticism and become valuable leverage for realizing the projects in building form, which is our ultimate goal.

As for the selections, New York was the obvious choice for a project about vandalism being the historic epicenter of street writing. Even in a heavily gentrified neighborhood like SoHo, buildings are still subject to being plastered by the creative underground despite the best efforts of civil authorities. Almost any area of New York City would have been a plausible site, but we chose SoHo specifically for the spatial paradigm established by its manufacturing history and the fact that its current incarnation as a bourgeois retail center is no longer connected to the creative culture it once supported. We based our building on 101 Spring Street, with its generous staircase and blank floorplates[1].

Bona fide art is conceptually opaque because it is inexplicably uncanny.

Our version is lightly embellished with what we call “conspiratorial” details: ledges that would grant access to blank portions of the building’s exterior, lips that would support makeshift scaffolding for getting at the undersides of skylight vaults (which could become makeshift canvases), and nodes projecting from walls that would allow large vertical surfaces to be scaled by only the most intrepid writers[2].

The Shibuya ward of Tokyo was our inspiration and location for the project on idiosyncrasy because it is exuberantly idiosyncratic. The densest parts of Japanese cities have an ad-hoc quality that would be dismissed as carelessness if it weren't for their unexpected tidiness. Shibuya is a shining example of this phenomenon showcasing a different building form on every lot (illustrations 1-5). A building based on exceptions and aberrations would go unnoticed in this neighborhood, and not simply because its buildings are so eccentric. The intense pressure exerted by Tokyo’s dense population on its real estate market makes it possible to imagine buildings with unconventional spaces being inhabited without compunction, effectively turning that pressure into an engine for architectural experimentation at the most intimate level.

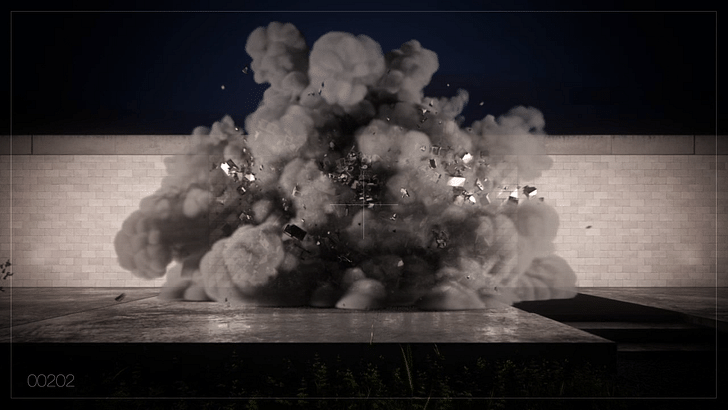

Finally, the scale of Detroit’s economic problems and the effect they’ve had on the city fabric are without precedent and it’s clear the city will never be the same. Some are even seeing the decline as a transformational opportunity, and an alternative economic system is developing as residents improvise and adapt. Interboro Architects’ “blots”[3] and Andrew Herscher’s “unreal estate”[4] are two compelling snapshots of a new Detroit rising to maintain communities through social and economic reorganization, and it would be profound if a new standard for beauty and creative expression emerged as a result. Considering the enormous potential locked in Detroit’s crumbling industrial and civic facilities, we felt a building that became more useful as it was destroyed might be a useful paradigm in this reinvention.

To me, the AAU films represent three different material approaches to architectural use; a triptych of experiential approaches to the “life” of architecture. The Soho project comes “alive” when left to the external intervention of vandalism; the Tokyo project is “activated” through each individual’s bespoke inhabitation of arbitrarily unique spaces; the Detroit structure transforms from a folly to an inhabited architecture through violent, irreparable actions. What idea unites the series of three for you?

The common thread between the three subjects is their pathological quality. In considering the organic nature of buildings, we found that the most revealing examples of organic development were pathologically driven - that is to say, at some level they subverted idealistic conventions for how buildings are conceived, built, or used.

I believe this is because pathological phenomena have a dialectical knack for laying bare the essence of the subject they afflict. Gordon Matta-Clark’s “anarchitectural” works are effective examples of this dynamic[5]. Mr. Matta-Clark’s building cuts are unquestionably destructive, but compositionally they have a transgressive and indifferent relationship to their subject. As a result the voids they define appear superimposed and treat the building as stock material. While the cuts and voids constitute the central ambition of these works, they also conjure a holistic reading of the building that transcends its constituent components and brings a vivid physical presence to the cognitive portraits of ‘building’ or ‘house’ that were previously locked in our imagination.

This conflation of the conceptual and physical is very similar to Bernard Tschumi's former fascination with the “rotten” Villa Savoye[6]. In his essay “Architecture and Transgression”, Mr. Tschumi characterized the derelict Villa as an epiphany in his search for a physical manifestation of immaculate space. For Mr. Tschumi, building construction is a process riddled with compromise in which the architect plays the doomed ideologue whose work must suffer the indignities of practicality. The Villa in its violated state transcended this problem by relinquishing any claim to perfection and deflecting expectations to the contrary. In an ironic twist, dilapidation accomplished what the most meticulous architects could not: a perfectly synthetic spatial experience in which the building’s decrepit physical fabric was a potent manifestation of its ideological promise.

Although both cases are compelling evidence in support of a role for pathological agents in architecture, it’s important to note that these examples reflect architecture’s characteristic idealism in assuming a building is an imperfect impression of the architect's true spatial and material ambitions. This definition casts the organic nature of buildings as an inherent problem that architects must defy or outwit. My interest lies in the existential question posed by these processes as they demonstrate the capacity for buildings to support a provocative cultural dialog from outside the bounds of orthodox design principles. It was our intention in the AAU project to shed light on this ulterior angle and bring it to bear on a legitimate architectural enterprise.

Explain (as broadly or specifically as you like) the procedure for creating an AAU film. How is the process dis/similar to the artistic process of modern cinematic filmmaking?

The process was inherently cinematic as the projects in the AAU series all have an organic dimension that can't be captured using architectural drawing conventions. The scenographic and narrative nature of filmmaking suited them very well, however, providing us with insight where sections and plans couldn't help. Furthermore, the projects could be presented with greater levels of nuance by leveraging film’s narrative aspect and introducing ideas that surrounded and supported the conceptual and cultural ambitions of each project.

For example, the vandalism adorning the walls of the SoHo project was a prolonged scenographic exercise in which the graffiti was constructed from field research and careful consideration for how the building’s details would facilitate its own defacement. The sales-pitch narration in the Shibuya sequence was written originally in Japanese and transposed literally for the English subtitles as a reflection of the cultural differences that drive the proposal, but also in homage to the enigmatic nature of architectural idiosyncrasy. The Detroit project’s music video format was an opportunity to re-cast the masonry as a malleable component of the building by pairing an atmospheric soundtrack with the choreographed drifting of the blocks into place. These are just a few instances where the medium of cinema became a tool for probing each subject in ways that brought new and valuable considerations to light.

Considering “being immersed” in architecture through film: Have you considered producing interactive projects, such as video/computer simulations, that allows the viewer to navigate architecture spontaneously?

It’s something we discuss quite frequently in the studio. As desktop units get more and more powerful, we’re seeing our work in real-time more often and in increasingly higher fidelity. It sometimes makes the hassle of rendering static frames seem ridiculous, and it’s easy to see a future where architectural visualization abandons cinematic presentation in favor of the interactive flexibility of real-time simulation. However, the AAU project didn't present an opportunity to work with this technology as real-time simulation still can’t produce the material nuance and detail we needed (at least, not with the technology that’s commercially available).

Graffiti occupies surfaces without permission or regard for the object it adorns in order to stake its claim within a system that it has overtly rejected.

Some shots required 14 hours of processing time for a single frame in order to capture what we needed to show, which is a far cry from the 30 frames per second we need for fluid motion. As a side note, we’re really looking forward to quantum computing...

That said, the Detroit proposal is overtly interactive, and early in the pre-planning of the AAU project we considered working with a gaming software development kit to study the demolition of its walls iteratively and with greater fluidity. Time didn’t permit it, but it still might be in the project’s future. Of course, it would be a profoundly different take on the project being it would lack the gravitas of the physical effort required to knock walls down by hand. But such a comparison would be very useful in an age where the promise of ubiquitous computing[7] has called the value of specificity and commitment into question.

Do you have any other, non-architectural experiences with filmmaking?

I did a few music videos earlier in my career, which is a fascinating genre that continues to influence what we do cinematically in the studio. I believe this is because music is fundamentally experiential, like a lens that tints reality. Through it banality can become profound, which is the kind of alchemical transformation that inspires our current work in architecture, especially as the work drifts further from a position that can be legitimately labeled as “design”.

A few of your projects reference graffiti/tagging as artistic expressions. What is graffiti’s artistic relationship to architecture? How do the two coinfluence each other?

There is a relationship, but qualifying the relationship as artistic makes it difficult to understand in terms that might be valuable to an architect. Nor does it do justice to the agenda of the street writer or the cultural value of their work. Bona fide art is conceptually opaque because it is inexplicably uncanny. By applying this definition as a metaphor through the label of “art”, we recognize our inability to articulate the importance of the subject to which it is applied, and subsequently we skirt a more interesting and challenging line of inquiry that promises to yield a better understanding of that subject.

Putting metaphors aside, we found graffiti’s relationship to architecture to be antagonistic in two important ways, each presenting a valuable architectural opportunity. First, it de-materializes walls and, as a result, destroys space. Murals of all stripes have this potential, but graffiti is particularly effective in this respect since it is often an illegible palimpsest of tags and garishness. The disruption and disorientation it brings is a specific kind of experience albeit one that lies outside the possibility of control by design. Second, graffiti is illicit by definition, and its value is tied to its subversive impact. Graffiti occupies surfaces without permission or regard for the object it adorns in order to stake its claim within a system that it has overtly rejected. It must steal in order to be accounted for in the subculture it represents, otherwise it becomes disconnected from that subculture and loses its cultural currency. As a primary agent of the system graffiti stands against, architecture cannot directly embrace graffiti without unraveling it. This conundrum makes an explicit cooperation between the two impossible, but it doesn’t rule out the possibility of some causal relationship.

To address these problems, our approach has been to conspire, not curate. This is reflected in the covert building details I referenced earlier from the SoHo proposal, but even contrivances like those can’t subdue the inherent conflict that makes their combination meaningful. To work with graffiti as a culturally-charged form of expression, architects must be willing to advance ideas in an act of obligatory concession knowing some will be destroyed or undermined by the street writers. As such, the relationship can evolve into a dialog, one responding in kind to the other, but it can never reach the intimacy of collaboration - and that’s a good thing.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.