Focusing on a defunct submarine wharf in the Port of Rotterdam, students in the Masters of Interior Architecture and Retail Design program at the Piet Zwart Institute explored whether interior design can give way to urban redevelopment. As part of last fall's [X]City studio, students proposed a spectrum of redevelopment strategies for the wharf, varying from commercial to artistic to recreational.

Under course director Alex Suarez, the projects imagine the interior world of the wharf as embodying an urban system beyond its boundaries, creating an “interior city” that both informs and enriches the outside reality. Phrasing interior design as city-building requires reinterpreting interior architecture’s goals, and how they’re evaluated. Interior architecture is primarily interpreted based on economic impact, as whether the “return on investment” justifies the project’s existence -- urbanism plays by completely different rules, where establishing ROI is based on a much fuzzier capital. [X]City tries to reconcile these rules, to create an interior space as nuanced and rewarding as its surrounding city.

As urban development strategies increasingly focus on re-purposing abandoned spaces, interior architecture stands to become a major mode of urban expression, not simply a strategic space to maximize ROI. The [X]City projects are ambitious and progressive, offering a different perspective on the urbanism of an interior.

Take a look at a few selected projects below, with summarized student descriptions.

A full acount of the [X]City studio and every student's project can be found here.

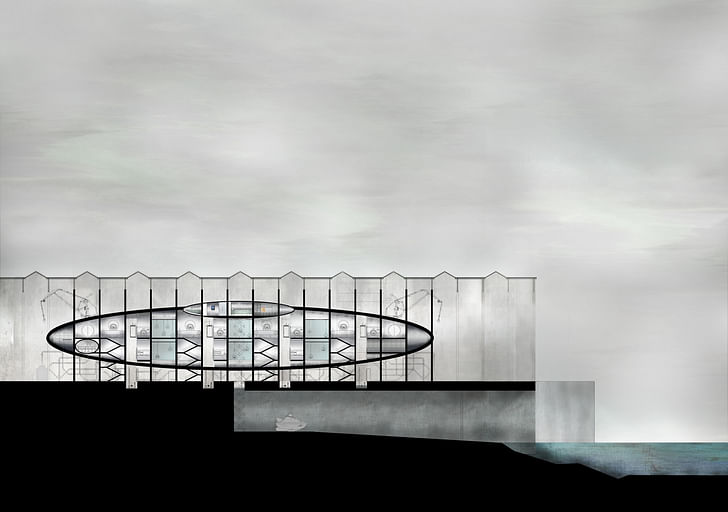

The Exchange City, by Maddalena Gioglio

The Exchange City is the Knowledge-Led Institute of the New Hanseatic League, a place that brings together and connects a cluster of Northern European port cities which share a number of cultural and economic peculiarities. This project was inspired by the Hanseatic League, a historical agreement between several port cities in Northern Europe for protecting economic interests and diplomatic privileges within towns and countries and along the trade routes. This historical reference is translated into a project that establishes a family of cities, bound by the cultural and economic links that continue to exist between them. The aim is to establish a logical and coherent network of cities that spans beyond national and regional plans. Hence the Exchange City opens a discussion for a further collective development which avoids the ‘levelling out’ approach of EU cities in promoting and projecting their development opportunities and resources.

The Port of Rotterdam plays a leading role in this project, by exemplifying the major impact of European city-ports, thus inviting discussion and initiating cooperation in different fields, with a focus on the revitalisation of old manufacturing techniques which once represented an important resource for the Hanseatic cities, but which have now been forgotten or reinterpreted in a nostalgic way. The revitalisation plan is translated into the Hanseatic Institute of Advanced Manufacturing, based on the research and exchange of this ‘forgotten’ knowledge.

On one hand the goal of the Exchange City is to establish Rotterdam as a landmark among other European cities, acknowledging its position as a positive interpretation of urban space and mutation. On the other hand the programme of the Exchange City offers a potential for regeneration of Rotterdam’s urban areas, such as Heijplaat, by providing its inhabitants with a space for social and economic encounters, therefore allowing them to re-emerge from isolation. The aim is to establish a new level of interaction between Heijplaat and the city: a geography of living and trade, a density and intensity based on the relationship between the two; an island which is not an enclave, but a city within the city.

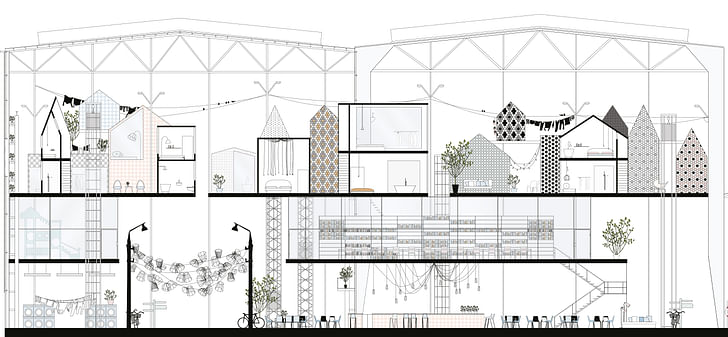

The space is organised according to a design strategy that provides a coherent structure within a generic grid which allows for adjustments over time. Common spaces arise from re-invented archetypes of squares and cloisters, while more clearly defined areas provide a location for various activities (training, meeting, workshops, conferences, accommodations). The various programmes are not scattered across the space, but placed according to the logic of the exedra, leaving room for spontaneous activities. All this is established through collisions/intersections of spatial elements, floating worlds and attractive terminals. The Exchange City in the Submarine Wharf provides a spectacle space, where the community of Hanseatic cities is transformed into an exciting hybrid. An interior-architectural artefact that merges the utilitarian (Heijplaat’s manufacturing identity) with the visionary (Rotterdam as a city of landmarks).

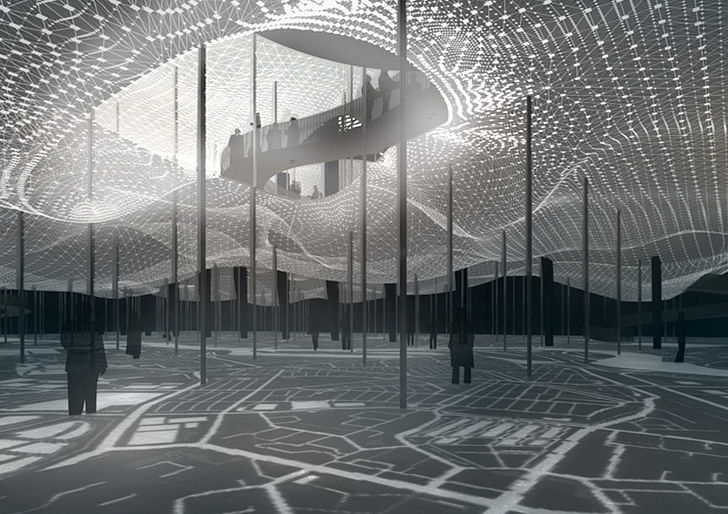

City Pulse: The City of Data, Egle Jacinaviciute

Today’s cities produce massive amounts of data, yet their residents have very little access or ability to understand this ever-increasing amount of information about the place they inhabit and share with others. Still, there has been an increasing interest in recent years toward the opening up and reusing of data for public needs.

The global tendency seems to suggest that city dwellers are no longer content to be mere consumers of the built environment – they want to be producers, creators, thinkers and hackers. Making data accessible and easily understandable allows anyone to use it, in ways that can benefit not only urban developers, but more importantly the lives of citizens. The intent for this project was to show the city as an organism, capable of variation, growth and decline, rather than an assembly of fixed parts. By revealing the pulse of the city, this project aims to show how technology can help individuals to make more informed decisions about the environment.

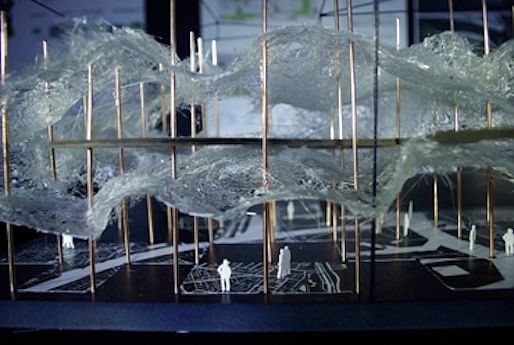

My project ‘City Pulse’ is a long-term indoor installation, which reflects the daily flow of Rotterdam’s motion by using real-time data to investigate and visualise constant changes within the city. The interior space becomes an installation in itself, where everyone is invited to join, see and feel the real-time pulse of the city. The idea is to reveal processes of daily urban dynamics in a very sensual way. The project will invite visitors to observe and visually enjoy the installation, but also to feel and analyse an experience in its own way. By transforming the city’s data into an emotional and visual experience, this installation stimulates an awareness of our living environment and provides a better understanding of the city’s dynamics.

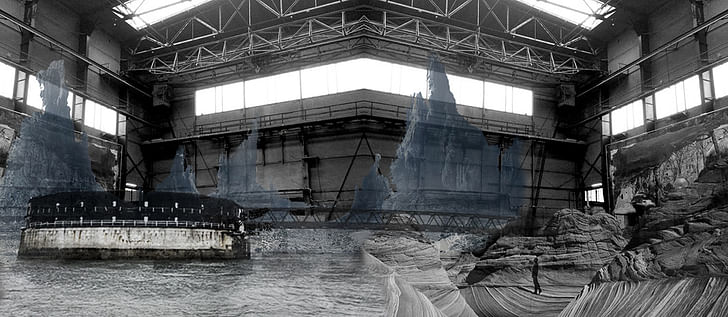

The installation ‘City Pulse’ uses Rotterdam’s traffic data as an open source. In order to visualise the liveliness of the city, I chose to use traffic as a metaphor for the circulation of blood in the human body – the most essential element which makes the heart beat and keeps a body alive. The activity of pedestrians, bikes, cars, ships, planes and trains is translated into an interior space using digital technologies. The inner structure is constantly changing according to the data received. The body of the installation is an amorphous structure that can grow or shrink, creating different volumes and interior spaces. Converting the collected data into the 3D experience provides a chance for Rotterdam’s residents and visitors to draw personal or collective conclusions as to what needs to be done in order to keep the city lively and functional. This also provides a newfound sense of ownership of the city, and creates possibilities for developing new relationships across local communities.

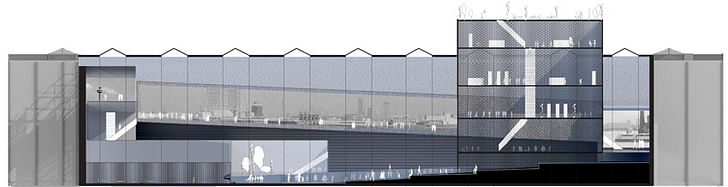

Fashionspace, by Sina Steiner

We live in an age in which everything keeps changing faster and faster. In fashion, these changes can be seen in each new collection. One season rolls into another with frightening speed. But the changes are not limited to the time periods and their collections; they can also be found in trends such as colours, patterns, fabrics or themes which influence the designs. Another aspect of these changes in fashion is the variation of the piece of clothing itself. Every fashion item, particularly clothing, changes with the movements of the person wearing that item – reacting and adapting to the person’s specific movements. But it also changes in its perception by others. Different people create a different look by combining certain pieces differently.

In architecture, we are facing similar changes. Many abandoned buildings and sites simply remain empty. Once they no longer fulfill their initial purpose, they become useless and are left to rest eternally in a kind of mummified condition. Today’s society moves very fast; the pace of change is dictated by trendy consumerism as well as technological progress. ‘Dead malls’ and obsolete factories are but two examples of this development. Nowadays, we as designers are charged with the task of blowing new life into these abandoned sites, in order to revive and reuse them.

My project ‘Fashionspace’ focuses on these changes. In my concept, a site which was once a submarine shipyard will be retrofitted into a headquarters for a well-established ‘haute couture’ fashion brand. The choice of location symbolises the brand’s cutting-edge market position. The site will undergo transformations far beyond the mere change of function. The contrast between the rusty industrial atmosphere of the old shipyard and the clean design of my interiors visualises these changes in materials and represents the new function. The Fashionspace reflects the brand’s culture and conveys its image as an open-minded and innovative brand.

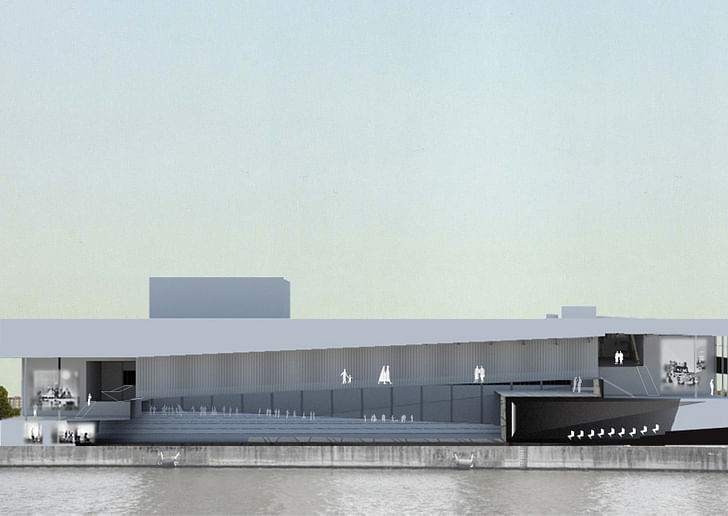

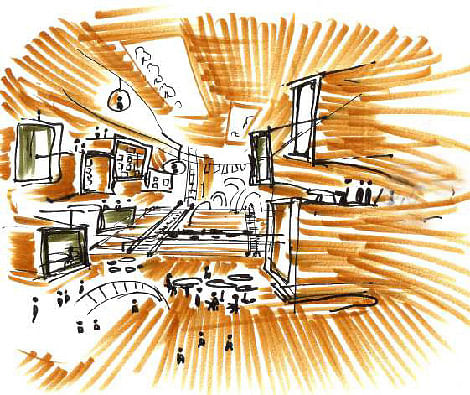

Heijplatt Hub, by Kine Solberg

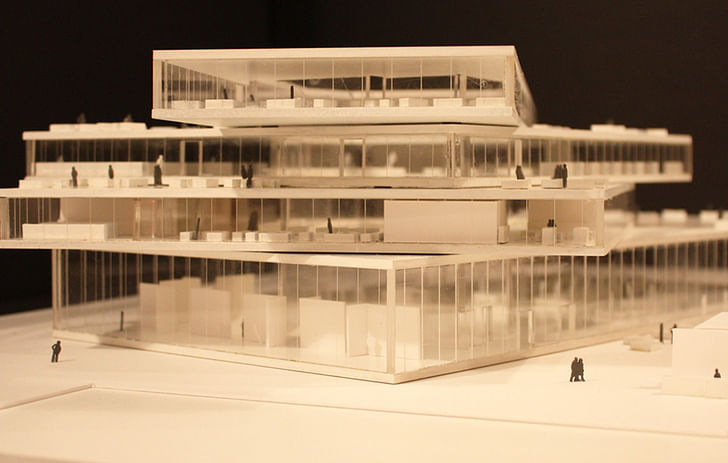

The Heijplaat Hub is a multidisciplinary office building, designed mainly to accommodate manufacturing companies. It is a cheaper, more flexible way of organising office rental in today’s market, with shared facilities and a focus on new innovations and inter-company collaborations. The Hub targets companies that are looking for both short-term and long-term tenancy in a fully equipped work environment.

This programme is a response to the current situation in the Heijplaat village as well as the surrounding areas of Rotterdam. The village is currently expanding by building a ‘new village’; however, there is a shortage of new inhabitants coming to Heijplaat, due to a lack of new jobs, a failing infrastructure, and limited facilities in the village area. The Hub also addresses an urgent situation in Rotterdam’s commercial rentals. Renting an office these days is a major investment for any company, involving often high monthly rents and deposits normally required for long-term lease contracts with the owner of the land or building.

Heijplaat Hub responds to the needs of the growing suburbs of the village, as well as the troubled rental market, by offering a space that allows both big and small companies to lower the risk of their operations, and providing basic services (offices, secretaries, canteen, meeting rooms, presentation halls, workshops for production, and exhibition space). Also, the Hub provides these companies with flexible working spaces that enable them to easily grow and shrink, by simply rearranging their rent contract instead of having to move to another location.

The Heijplaat Hub will also add value to the community through the flexibility of the space; although the main use of the wharf is the rental of commercial space, the unoccupied areas are made available to the Heijplaat village and the general public of Rotterdam. These areas can be seen as a sort of public plaza, where the villagers, the companies, and the general public of Rotterdam can organise large gatherings such as markets, exhibitions, indoor parks, gyms etc. Thus, the Hub and its companies benefit by promoting themselves and their work, while the people of Heijplaat gain a new public arena with a new sense of flexibility and an industrial atmosphere.

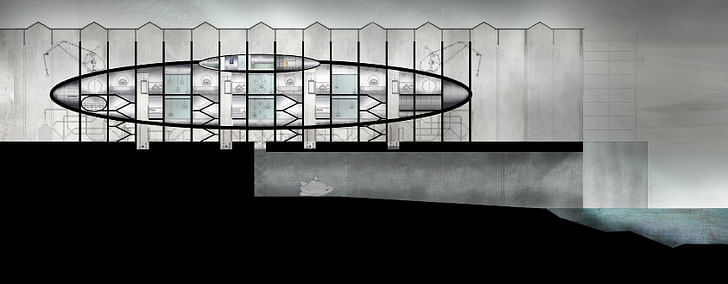

The Incubator, by Joanna Choueiri

A science fiction:

Historically, the village was built because of the port, with an important submarine wharf located at the edge of the village. Only people working in the port were allowed to live in the village. With the expansion of the port, and its relocation to another part of Rotterdam, city-ports such as Heijplaat were threatened with extinction.

In an effort to help the village, the Port Authority proposed various scenarios for turning Heijplaat into another kind of village, one which would be attractive to new residents. The villagers thought differently. The changes brought about by the Port Authority and the municipality of Rotterdam – such as the building of new housing structures – meant that the population was becoming more diverse and more ‘foreign’ to the original population of the village.

Then the revolution took place. The villagers stood up against the outside forces and took matters into their own hands. They sought the help of Nico, a scientist, to create a factory/laboratory for the production of human beings. These humans would become model citizens of Heijplaat, living here and working in the port. The wharf, which was the reason the village was built, was the ideal location for Nico’s laboratory.

The Heijplaaters would provide him with their DNA through a series of machines which brought the samples to the lower level of the laboratory... The wish of the Heijplaaters was achieved. Nico and his laboratory had become a part of their everyday lives. The town was full of healthy young people, all of them interested in nothing but the port... The village was saved, but at what cost?

My City Is My Home, by Natalie Konopelski

I am rethinking strategies for residential design, from the macro to the micro scale. By interpreting the urban, public and private spaces in a new way, I wish to create a higher density and physical interconnectivity throughout the city, and thus to build an urban landscape of coexistence. Following the logic in which public space, interactive units with shared facilities, and the interior space are all related, I wish to promote community and interaction as well as individuality, identity and intimacy.

In this case, my design strategy is to approach the city from a personal and subjective point of view. Over the course of time, the cities I have lived in all became my home. Having moved only recently, I once again ‘found’ a new home in Rotterdam. Thus, I am claiming that my home is the city. Cities are complex and layered organisms, and by analysing them I extracted three basic structures:

My city consists of urban, communal and private space, but interpreted in a new way, resulting in a mix of structures of privacy within a city and a house. My city becomes a framework for stimulating interaction among people, and is organised into three levels:

The (One Man) City, by Nathalia Martinez Saavedra

The idea for this project is to enable a discussion on the issues of density and land ownership in today’s overpopulated cities. The One Man City experiments with the utopian notion of dividing the earth’s land equally between all humans. According to this hypothetical division, each of us would have approximately one hectare of fertile land in which to sustain ourselves and create our own living space.

This project unfolds possible scenarios for this one-hectare interior space inhabited by just one person. The Submarine Wharf in Rotterdam seems a suitable place for this experiment: not only considering its large footprint and its peculiar location between the main city and the industrial port, but also taking into account the fact that it is located in one of the densest countries in the world – which, ironically, is now facing a large vacancy problem caused by real-estate driven development.

The project raises questions about the verticalisation of the city, the stacking of living spaces, contemporary community life, and a growing society whose members are becoming more self-sufficient and individualistic, and thus more solitary.

Considering that the One Man City is experienced in isolation, silence, contemplation and autonomous survival, all aspects involving social relations and community exchanges are excluded here.

The experience of inhabiting your equal share of Earth’s land allows for a mirrored and ironic reflection on the densification of cities. Therefore this playful yet political approach can enable the evolution of a social transformation, as a part of a new urban system based on equality, self-responsibility and aspects of sustainability, integrating individuals as the main protagonists of their own microcosm within the city.

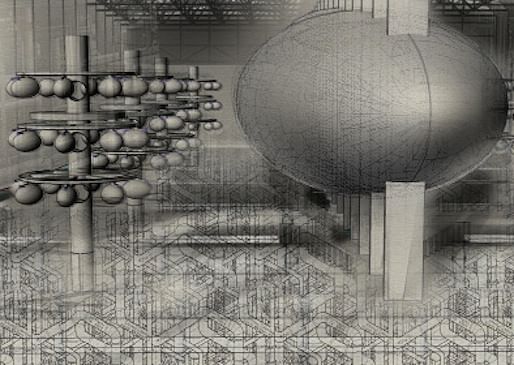

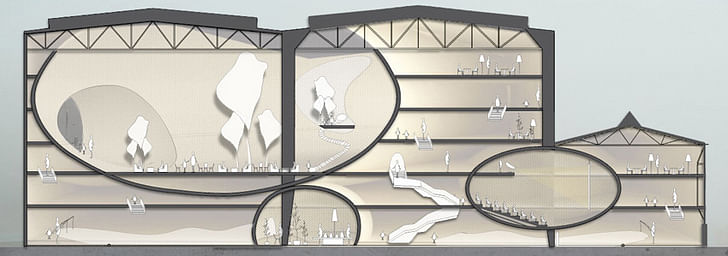

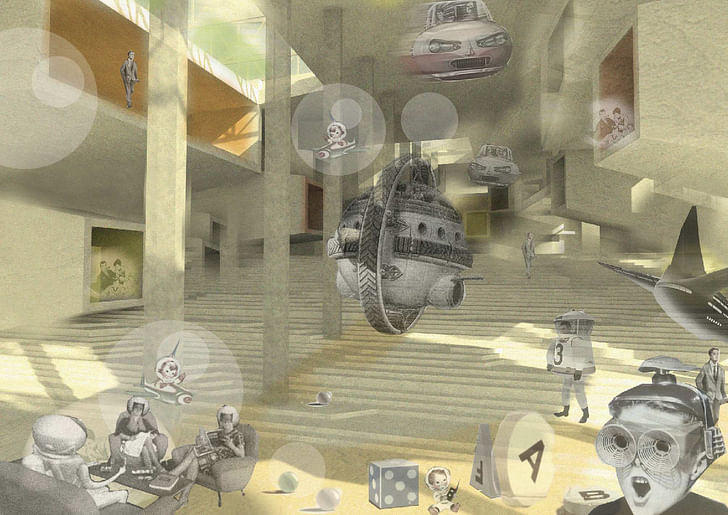

The Playground City, by Giulia Cosenza

The project ‘Playground City’ reveals the existing situation in Heijplaat, by creating a recreational space for the community of businesses currently operating at the RDM (Research, Design & Manufacturing) Campus. The project addresses the entire community, with a focus on children since the project operates as an extension of the educational processes that take place in the city’s schools. The result is a hybrid of play and work, a workshop space that reinterprets and stages the main vision behind these businesses: technology and innovation, the merging of nature and built environment, inside and outside.

The project has a broader social meaning for Rotterdam, as it investigates a new typology of educational and entertainment space which takes into consideration the lack of funding for high-quality public recreational spaces for kids, creating a hybrid structure between public and private organisation.

‘Playground City’ is based on a simple statement: we can appropriate the space when it is open to our imagination. The act of playing is free, non-hierarchic and open to any experience and discovery. It becomes a strategy for shifting from machine to human, similar to the shift from an industrial society to an information society.

The Utopian Family Town, by Albina Aleksiunaite

The RDM Campus and its neighbourhood are suffering from the presence of a ‘wall’ separating two communities, or in other words, two cities. The first community is Heijplaat: a village district, built according to utopian modernist ideas as a ‘garden village’, an ideal city for industrial workers. The second ‘city’ is the RDM Campus: a former working place for these same workers, but now occupied by ‘outsiders’, the area’s current inhabitants. These pioneering newcomers have transformed the abandoned factories into a headquarters for technical science, research and education. Such economic changes have created a social separation, a dividing ‘wall’ between these two communities, the locals and the newcomers. I therefore decided to investigate how this ‘wall’ could be demolished: how the border between the two communities could be eliminated, allowing them to communicate and interact. What must be done in order to end the current spatial and social separation?

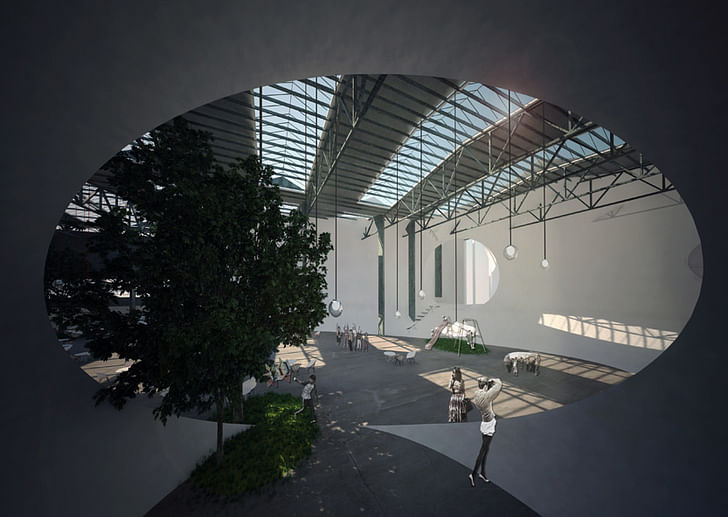

My answer and intention would be to introduce the characteristics of the utopian Heijplaat ‘garden village’ into the RDM Campus, establishing a new modern ‘garden village interior city’. This way, the Heijplaat community would mix with the newcomers, and the two societies would gradually merge over time. The dividing social ‘wall’ would disappear. The first intervening ‘interior city’ would be established in an appointed submarine wharf building; later, when the population reaches a peak, another intervening city could be established in another empty submarine wharf building. Through this strategy, the whole area would gradually become one organism.

In my proposal, the new ‘garden village interior city’ would be built by borrowing utopian ‘garden village’ qualities and translating these into a ‘contemporary social town’ called ‘The Utopian Family Town’.

About the Piet Zwart Institute's Masters of Interior Architecture and Retail Design:

Text is paraphrased from Alex Suarez and Petar Zaklanovic's contribution to the the Piet Zwart Institute's full description of the program.

Project Description

This thematic design project was structured to include integrated history and theory, research methods, visualisation, and fabrication modules. The theme explored large-scale interiority, urbanism, and the re-use of a vacant industrial building in the Port of Rotterdam called the Submarine Wharf – originally a covered slipway for making submarines. The building and its location outside the city posed an array of challenges inherent to the repurposing of very large buildings in decentralised, industrial urban areas.

Site - Submarine Wharf Port of Rotterdam

A hybrid of architecture, urban planning and interior design seems the inevitable course of action – yet this approach is rarely applied in practice.The test ground for this project was the former Submarine Wharf, a building with an area of approximately 8,000 m2. The Wharf is located on the southern bank of the Maas River, in Heijplaat, a peninsula within the Port of Rotterdam, which also includes a garden suburb developed in the period between the two World Wars.

The Port of Rotterdam has moved its activities further towards the sea, creating challenges for the built-up areas left behind. The loss of these areas’ main purpose and function is further complicated in this case by Heijplaat’s extremely isolated position within the city of Rotterdam. There is no substantial public transport connection between this area and the rest of the city; travelling to Heijplaat from the centre of Rotterdam takes as long as a trip to Amsterdam. In recent years, a variety of former port-related buildings on the site, which had been vacant for quite some time, have been reused as working, educational and office spaces. As a result, an interesting new community is now in the making.

Interior City Basics

Speculative urban development over the past few decades, combined with more natural and gradual urban transformations as well as a decrease in urbanisation and a plateau in key demographic trends, have left behind an abundance of vacant built structures. Of ten scattered, sometimes concentrated, truly resembling cities within cities, these spaces are now widely being discussed, and increasingly perceived as opportunities in urban development. There is thus a clear need for strategies and methods for their exploitation and integration into ambitious plans for urban renewal.

In order to reap the benefits and mitigate the obstacles, the design of such built structures naturally must go beyond conventional methods, combining applicable techniques with knowledge of all relevant disciplines. A hybrid of architecture, urban planning and interior design seems the inevitable course of action – yet this approach is rarely applied in practice.

Interior City for all

In the typical neo-liberal reality, any investment in a built structure is founded on a clear, though usually very complex business model: eventually there should be some kind of return on the investment. This is, much more than in urban planning, the case in the realm of interior design, where regardless of their actual qualities, the spatial designs for specific programmatic propositions are seen and judged almost solely as a collateral to the financial success of the underlying business plans.

In this situation, ensuring the public interest/value/programme, so essential to the ambition for conceptualisation of an interior city, becomes a fragile but a vitally important pursuit, since a city is not only about the maximisation of profit, but should be for everyone and about freedom of choice and interpretation. In the triangle formed between market-driven development, governmental regulations and relevant design disciplines, a number of different equilibriums can be established. They all result in specific spatial constellations, each with its own balance between the private and public realms.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

1 Comment

I found this a hard problem to wrap my head around, but a good one. If I understand the intent with the question - Interiors are almost strictly ROI, but urban planning is social and more. Therefore, in a way urban plans allocate the best spots for ROI interiors.

maybe one way to think of it, if I piled a bunch of interior spaces in a row down a street away from a park or plaza at what distance does the ROI drop...so scale this problem down into interiors and you essentially enrich the interior while increasing ROI? (my city is my home?)

The only thing I'd add to the 'City Pulse' is put some designer and developer desks in the space and see what they would come up with while working in that space all day.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.