Zawia is a relatively young and highly ambitious architecture publication, one that places a strong emphasis on community politics with global connections. Coordinated between representatives in Cairo, Milan and London, Zawia also produces a series of collaborative events on architecture, design and urbanism, while basing its publication in Egypt. This multi-national collaboration is a indicative of Zawia’s purpose, to help dissolve the Middle East’s intellectual isolation from global architectural discourse and create an open discussion still rich in local perspectives.

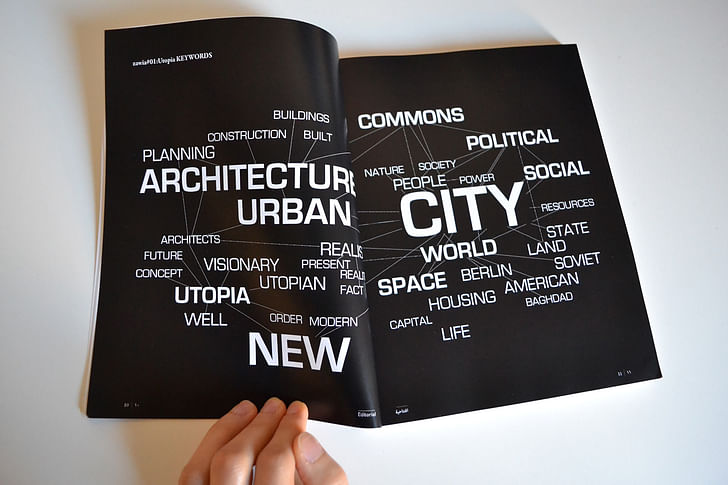

Issue #00, “Change”, was published in 2012, after Hosni Mubarak had fled from Cairo and in the midst of Mohammed Morsi’s election. Embedded in a destabilizing but hopeful time in Egypt, “Change” has since evolved into “Utopia”, Zawia’s issue #01, featured here. But that title is in no way a declaration of a discovery or solution, but instead a means to re-asses presumptions of urban values and directions. Examining particular trends in both architectural design and academic discourse, “Utopia” accepts that such an extreme is effectively a paradox: that we need to abandon any hope of utopia to achieve it, and embrace the smallest of possible improvements within our shared chaos to do so.

From “Utopia”, Screen/Print is featuring Amale Andraos’ piece, “Visionary Urbanism and Its Agency”. Andraos is the founder of WORKac, an architecture firm based in New York City, convinced of architecture’s ability to stage and create positive human relationships. Her piece for Zawia is an outline of the myths surrounding a concept she calls “Visionary Urbanism”, the architectural movements that attempt to radically renew a certain aspect of society for the better, albeit with inevitable problems. Whether praised or condemned, visionary urbanism is often shrouded in myth and misunderstandings, which Andraos attempts to explain through studies of discrete trends in contemporary architectural discourse.

VISIONARY URBANISM AND ITS AGENCY

Amale Andraos

“It’s important to really try to understand what failed and why. I think we have a responsibility to understand those failures… to learn from them and to do better”.

Robert Fishman in the Pruitt-Igoe Myth

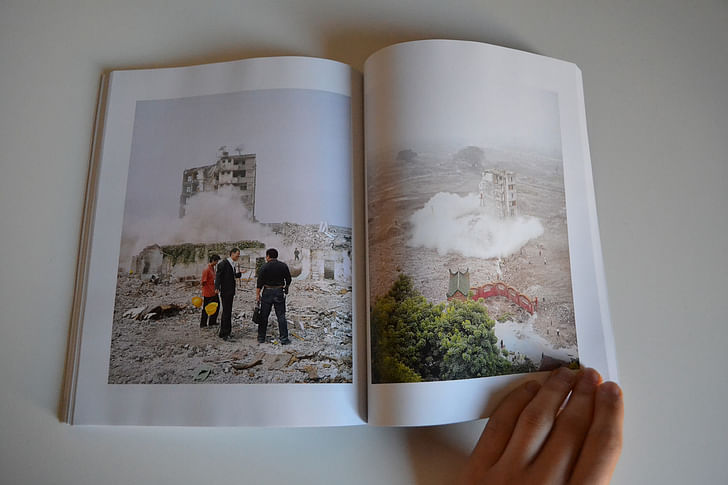

For architects, utopia is not a ‘no place,’ but a body of very real images, events and consequences that are continuously operating on our architectural and urban imaginations: on the one hand, Radiant City’s towers standing in an idyllic park and on the other, the footage of Pruitt Igoe’s destruction continuously replayed whenever it is time to reaffirm the death of progress, of modernism or of ‘the Future.’

It is those images that I would like to term Visionary Urbanism, understanding their power as agents of change that operate differently from that of utopia. Whereas both utopia and its dystopian other are located within our imagination as either idealized or darkened versions of reality, Visionary Urbanism is in contrast very much embedded within the realities it is trying to transform. It is this small yet important difference, as well as the long and varied history of these visions-made-real that continues to render Visionary Urbanism so productive as a tool in the reshaping of our environment. Despite its pitfalls, Visionary Urbanism’s unique strength lies in its unconditional engagement with projecting the future - an engagement that is much needed today. To move forward, the Visionary mines the past, not in the service of existing audiences but to produce new ones and the possibility of different futures. The Visionary is always problematic, simultaneously seductive and polarizing: faced with the too pragmatic or the too complacent, it radicalizes to open up new directions and create new positions. It is this incredible potential that architects continue to channel, yet without a full grasp of Visionary Urbanism’s precise contribution to change. Caught between holding the practice responsible for everything or for nothing at all, one must first extract the history of Visionary Urbanism from the seemingly unshakable myths of its crimes, to enable its full engagement as a progressive tool. It is this untangling that this essay begins to address.

FIRST MYTH: THE MYTH OF FORM’S CAUSAL RELATIONSHIP TO SOCIAL ORDER

Of all the myths that have plagued Visionary Urbanism, the one that rendered it hopelessly guilty in the public eye for most of the second half of the twentieth century is that of a self-evident cause-to-effect relationship between form and its supposed resulting social order. While the Visionary’s intent is most certainly to produce new possibilities for the social through its formal projections, the connection between one and the other is a result of many other intersecting factors - specific contexts whether cultural, economic, political or social – that contribute to wildly differing outcomes despite the implementation of similar formal and typological strategies. Of all the ‘visionary types,’ the one held most often accountable, embodying society’s worst ailments, is that of the Tower in the Park model. In the United Visionary Urbanism does not have to rely on its implementation to reach its full potential; it only needs to exist as a powerful representation, a vessel for projections and positions.States, New Urbanism has perpetrated this myth aggressively since the publication of its manifesto Suburban Nation, and despite the abundant examples proving otherwise globally.

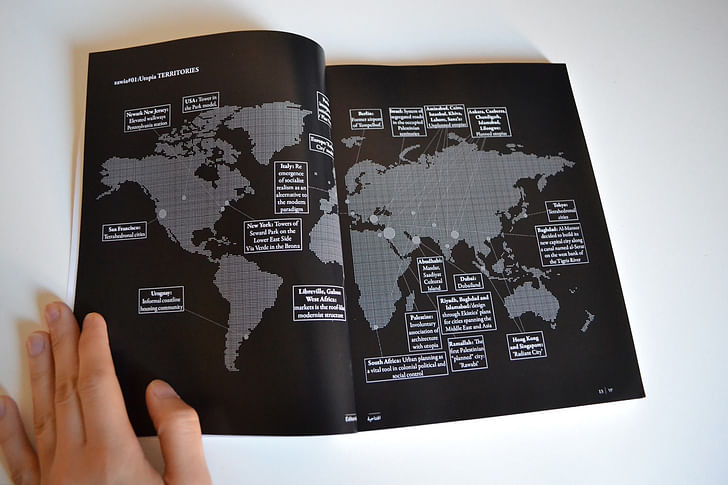

Today, there are numerous examples of Towers in the Park around the world that undermine the type’s ‘guilty as charged’ status. In New York for example, the success of this type is demonstrated across the island, from the towers of Seward Park on the Lower East Side, to the much-coveted Stuyvesant Park at the edge of Downtown or the recently completed Via Verde in the Bronx. In Europe, one cannot help but understand the failure of the ‘Radiant City’ model, isolated within or on the outskirts of urban centers, as a scathing failure to integrate various immigrant populations over time rather than as a consequence of the towers’ architecture or the design of their setting. The recurring burning suburbs of Paris, forcefully depicted in the movie La Haine, rendered visible to the world the desperate conditions in these projects-suburbs. There, almost three generations of North African immigrants continue to suffocate, certainly less because of the crumbling urban scape around them than because their surnames – Mohamed or Jamilah – have hindered their ability to get jobs to improve their living conditions. In contrast, ‘Radiant City’ is thriving in certain cities in Asia such as Hong Kong and Singapore, where it was implemented within highly effective and supportive public infrastructure. Amongst the most convincing recent defenses of the type is that presented by the documentary ‘The Pruitt-Igoe Myth’ released in 2012, which poignantly retells the story of a failure not of vision of architecture or urbanism, but rather of everything and everyone else around: the conservative and racist time and place in which these visions were made real.

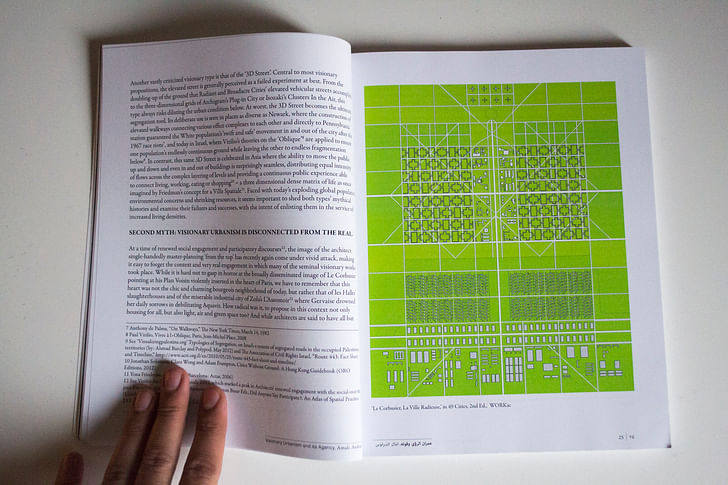

Another vastly criticized visionary type is that of the ‘3D Street’. Central to most visionary propositions, the elevated street is generally perceived as a failed experiment at best. From the doubling-up of the ground that Radiant and Broadacre Cities’ elevated vehicular streets accomplish, to the three-dimensional grids of Archigram’s Plug-in City or Isozaki’s Clusters In the Air, this type always risks diluting the urban condition below. At worst, the 3D Street becomes the ultimate segregation tool. Its deliberate use is seen in places as diverse as Newark, where the construction of elevated walkways connecting various office complexes to each other and directly to Pennsylvania station guaranteed the White population’s ‘swift and safe’ movement in and out of the city after the 1967 race riots, and today in Israel, where Virilio’s theories on the ‘Oblique’ are applied to ensure one population’s endlessly continuous ground while leaving the other to endless fragmentation below. In contrast, this same 3D Street is celebrated in Asia where the ability to move the public up and down and even in and out of buildings is surprisingly seamless, distributing equal intensity of flows across the complex layering of levels and providing a continuous public experience able to connect living, working, eating or shopping – a three dimensional dense matrix of life as once imagined by Friedman’s concept for a Ville Spatiale.

Faced with today’s exploding global populations, environmental concerns and shrinking resources, it seems important to shed both types’ mythical histories and examine their failures and successes, with the intent of enlisting them in the service of increased living densities.

SECOND MYTH: VISIONARY URBANISM IS DISCONNECTED FROM THE REAL

At a time of renewed social engagement and participatory discourses, the image of the architect single-handedly master-planning ‘from the top’ has recently again come under vivid attack, making it easy to forget the context and very real engagement in which many of the seminal visionary works took place. While it is hard not to gasp in horror at the broadly disseminated image of Le Corbusier pointing at his Plan Voisin violently inserted in the heart of Paris, we have to remember that this heart was not the chic and charming bourgeois The case of the ‘planning’ of Tehran demonstrates almost through irony how intertwined formal and informal can be, relying on one another to produce the ebullient urban conditions we long for as architects.neighborhood of today, but rather that of les Halles’ slaughterhouses and of the miserable industrial city of Zola’s L’Assomoir where Gervaise drowned her daily sorrows in debilitating Aquavit. How radical was it, to propose in this context not only housing for all, but also light, air and green space too? And while architects are said to have all but abandoned the pursuit of public housing, we have nevertheless inherited the light and air regulations, setbacks, zoning envelopes and sky exposure planes, first germinated in Radiant City and later developed through CIAM.

Hand in hand with this image of disconnected idealism is that of a lack of engagement ‘on the ground.’ Yet, from Le Corbusier to Frank Lloyd Wright or Ebenezer Howard, to name but a few, there is a long history of active political engagement to press for ones’ vision and make it real. One of the most striking examples combining vision and pragmatism is Howard’s manifesto for the meeting of Town and Country in his proposed Garden Cities. Beyond the idealized network of perfectly bounded cities, Howard had worked out all the minor economic details of his city-as-cooperative, building financial models he was able to present to the developers of his time, forging various alliances until the first Garden City, Letchworth, was built albeit vastly transformed, in 1904.

THIRD MYTH: ‘IT’S JUST PAPER ARCHITECTURE...’

Visionary Urbanism does not have to rely on its implementation to reach its full potential; it only needs to exist as a powerful representation, a vessel for projections and positions. Few images have had the staying power of Superstudio’s 1969 Continuous Monument - whether it is used to lament the grip of globalization, to warn of architecture’s suffocating powers while simultaneously demonstrating its ability to resist, or to invite a hedonist post-consumer life without objects (or even clothes.) It is those images, capturing the ethos of the Radical movement in Italy, whose reach influenced generations of architects as wildly different as Ettore Sottsass, Emilio Ambasz or even Rem Koolhaas. Another series of seminal images - ‘positive utopias’ which have operated quite differently - are Buckminster Fuller’s Tetrahedronal cities floating in the bays of Tokyo and San Francisco. Proposed for one million inhabitants each, Fuller’s pyramids are radical forays into the questions of density, human settlement patterns and ecological infrastructures necessary for a sustainable future. While Fuller’s domes never became much more than a shrunken version of themselves in implementation, his thinking’s reach manifested itself in the work of active practitioners such as Doxiadis, whose obsessive diagramming of networks and flows followed Fuller’s lead as he attempted to inscribe humans as but one part of a much larger environmentally sound whole. This ‘design through Ekistics’ as Doxiadis coined the term, resulted in a number of master plans for cities spanning the Middle East and Asia, such as Riyadh, Baghdad and Islamabad. Setting aside the common failure of his city blocks to produce the density and life he was set on promoting, his active integration of environmental performance as a key ingredient of design is still one of the most complex manifestations of environmental concerns in modern urban planning and architecture. It is those same concerns that Hassan Fathy, a long time junior architect in Doxiadis’s practice, was able to carry further and transform to include an exploration of architectural language that promised to hold the possibility of meaning as well.

FOURTH MYTH: THE INFORMAL AND THE FORMAL ARE OPPOSED.

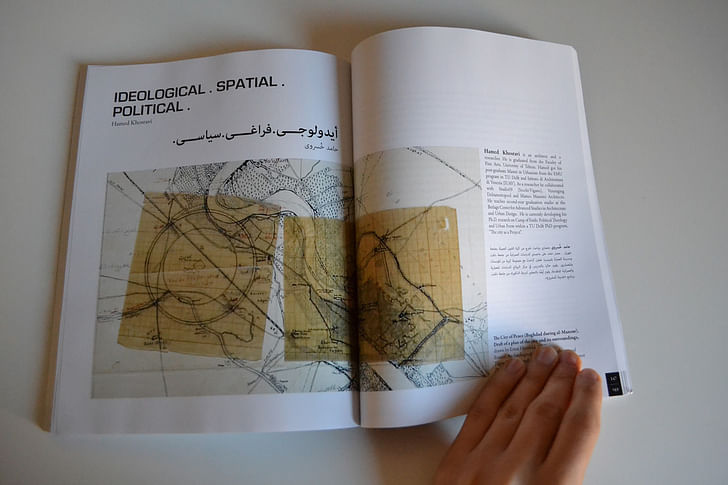

In his article entitled ‘Ideology as the Achilles Heel: Planned vs Unplanned in Tehran and Amsterdam’ architectural historian Wouter Vanstiphout discusses how Tehran, a quintessential city of ‘organic growth’ and informal character owes its current setting to a master plan it systematically denied. The article describes how in 1963, the Shah launches the White Revolution to propel Iran and its capital towards modernity. Conceived by the Viennese architect Victor Gruen in collaboration with Abdol Aziz Farman Farmaian, the proposed plan is exemplary in its minute regulations, allocated building densities, careful distribution of open green spaces and transportation infrastructure. After the success of the Islamic Revolution, the plan came to embody for Ayatollah Khomeini ‘the West’ to be despised. Yet, rather than being abandoned, the plan morphed into a blueprint for its opposite: a map to be negated through systematic violations of its guidelines and principles – whether maximum building densities, zoning regulations or the preservation of open space.

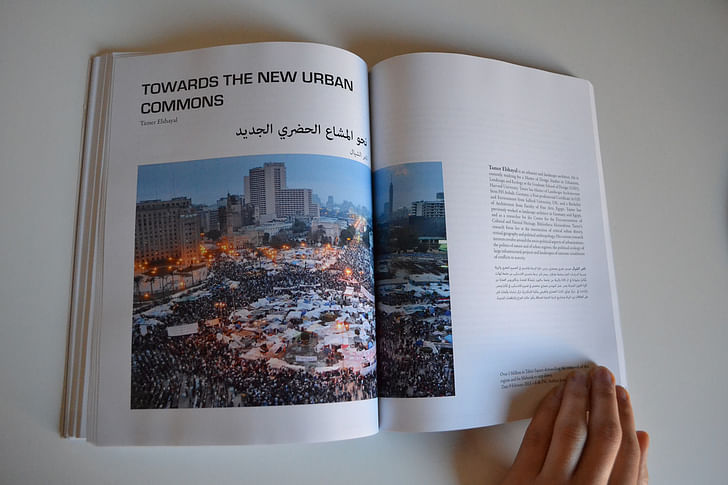

As an extreme example, the case of the ‘planning’ of Tehran demonstrates almost through irony how intertwined formal and informal can be, relying on one another to produce the ebullient urban conditions we long for as architects. This intertwining can be found across the world, where informal gatherings such as markets thrive on underlying infrastructures, which they feed on while undermining all at once. In West Africa – a beautiful example of such markets is the roof-like modernist structure designed by architect Marcello D’Olivo in the outskirts of Libreville, Gabon. In the Middle East, the recent demonstrations and revolutions – informal gatherings charged with producing change - have crystallized within the most highly symbolic and formalized public spaces.

FIFTH MYTH: THE ‘UNPLANNED’ (IS BETTER, FREER, MORE AUTHENTIC AND ‘BOTTOM UP’)

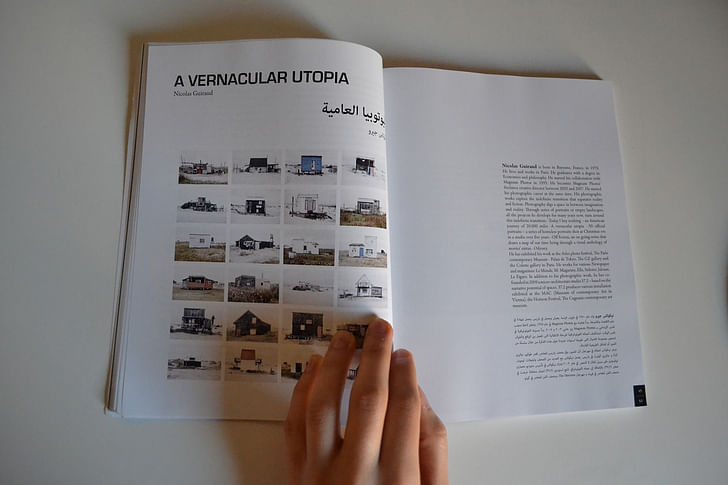

In many ways, there is no such thing as the ‘unplanned’. The renewed interest that architects and urban planners have shown in slum conditions over the past decade has demonstrated again and again how informal settlements’ perceived chaos in fact hold an incredible underlying structure. They function using the kind of ‘soft infrastructures’ that are often more flexible and adaptable than those around which traditional cities were built. In the light of these observations, the ‘unplanned’ is rendered just another myth, today heralded most by the neo-liberal market-rule ideology it has come to serve. In most instances, the ‘unplanned’ has become all but an excuse for unregulated development, able to deploy itself in the form of endless sprawl and cheap building, maximizing profit at the expense of social or environmental concerns. This short-term vision excludes the The ‘unplanned’ has become all but an excuse for unregulated development, able to deploy itself in the form of endless sprawl and cheap building, maximizing profit at the expense of social or environmental concerns.possibility of master planning long-term infrastructures, without which it is near impossible to build sustainably. It is this ideology of the ‘unplanned’ which has come to characterize much of the debate around the American suburb for example, always heralded by its supporters as representing the essence of what it means to be American - with ‘individual freedom’ reduced to the symbolic tandem of white picket fence and defensible lawn. From the Federal Highway Act of 1956 and its implied unconditional support for the car, to the tying of the American dream to the particularities of a consumer-obsessed suburban lifestyle there was nothing ever ‘unplanned’ about the American suburban model. Today, it continues to be planned at massive scales almost exclusively by developers.

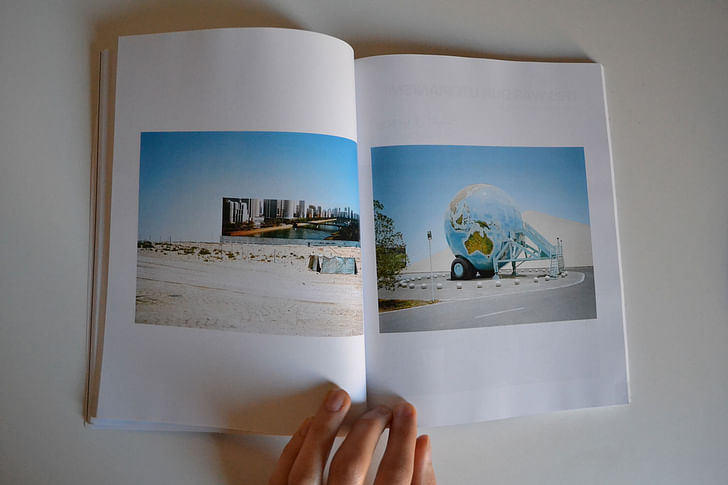

And yet, resistance to any kind of alternate planning that would embrace higher densities, collective open green spaces, public transportation or diversity (of people, incomes, species etc…) persists despite the outrageous cost to its inhabitants, the environment as well as the rest of the world. As the ‘unplanned’ itself becomes a model, it is exported, multiplied and turned into its ultimate inversion, gated communities. With no vision other than a profit-driven one, this model begs for engaging and provocative representations, visionary propositions that both criticize and project alternate modes of living.

CONCLUSION

The need to think the future necessitates the visionary, the polemical and the radical. The theme of this publication enables us to focus the question of the visionary and its possible agency in the Arab world, as it violently rejects the status quo that has boxed it in for decades. There is a long history of incredible progressive thinking in the region from which there is still much to learn – both in terms of successes and failures – towards shaping a different progressive future for the next generations. This future will move beyond constructed oppositions such as ‘the mosque and the square,’ to define new possibilities for the articulation of public and private spaces in the Arab City.

Most importantly, it is a matter of urgency to reclaim ‘the visionary’ from the discourse of too many rulers in the region, who represent a dangerous combination of neoliberalism and religious fundamentalism. Finally, it is vital that architects move beyond the endless Orientalist designs plaguing the region, from the ‘traditional city’ of Masdar to that of Nouvel’s Louvre on Saadiyat Cultural Island. Enlisting the power of images and the imagination, a progressive redefinition of democratic civil society will engage Visionary Urbanism as a tool to reject the boundaries of the accepted possible while passionately projecting the still impossible.

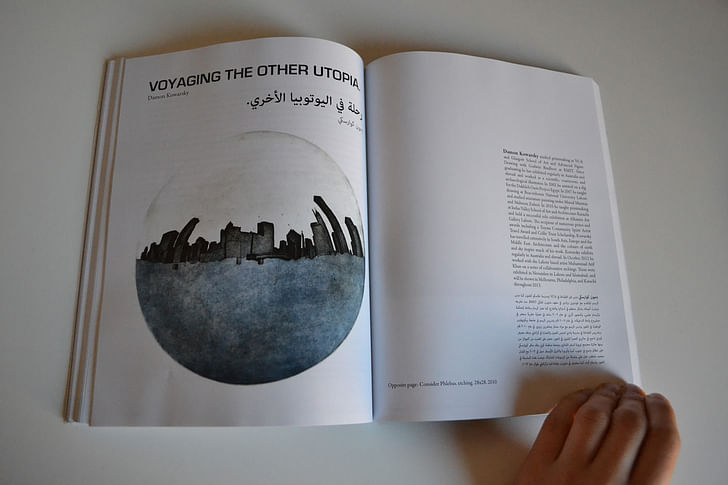

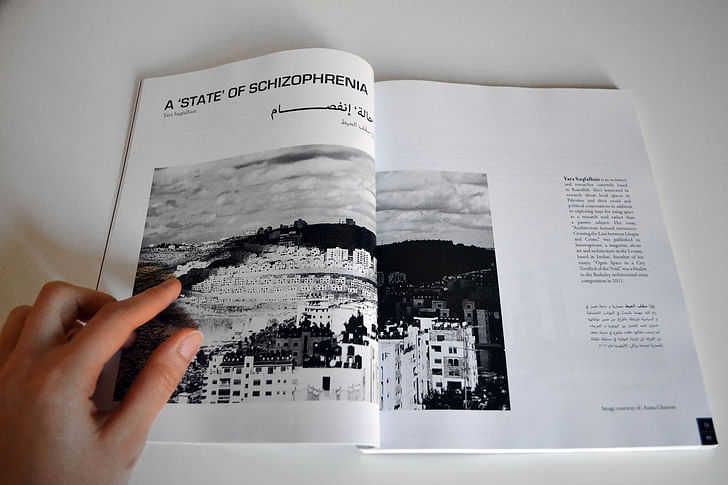

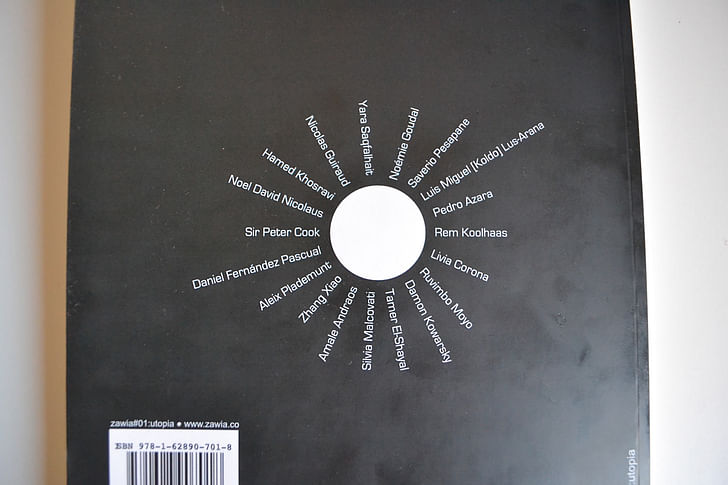

Zawia #01: "Utopia" (published December 2013) is now available for purchase, featuring contributions from: Yara Saqfalhait, Rem Koolhaas, Nicolas Guiraud, Noel David Nicolaus, Daniel Fernández Pascual, Aleix Plademunt, Sir Peter Cook, Ruvimbo Moyo, Damon Kowarsky, Silvia Malcovati, Tamar El-Shayal, Zhang Xiao, Hamed Khosravi, Noémie Goudal, Luis Miguel [Koldo] Lus-Arana, Saverio Pesapane, Livia Corona and Pedro Azara.

Screen/Print is an experiment in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

For this issue, we’re featuring Zawia #01: Utopia.

Do you run an architectural publication? If you’d like to submit a piece of writing to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.