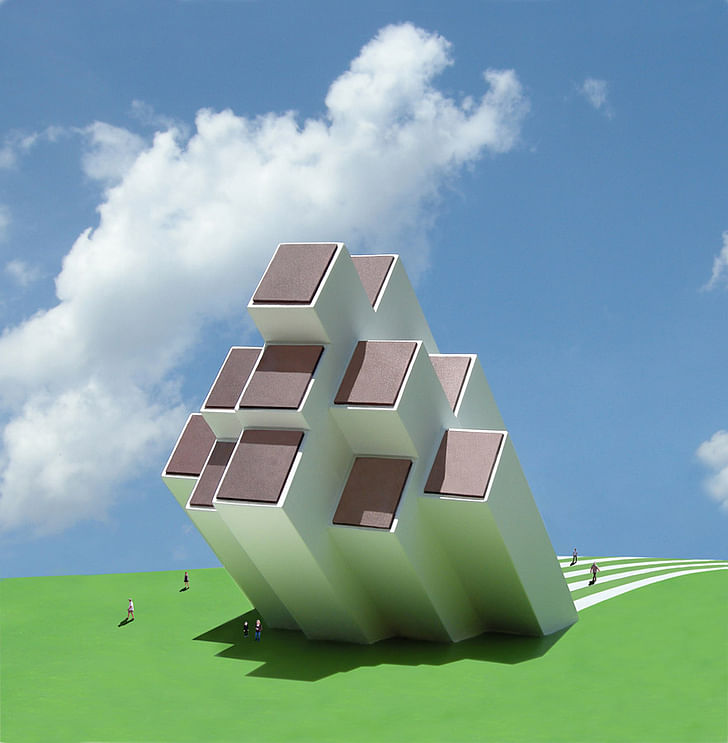

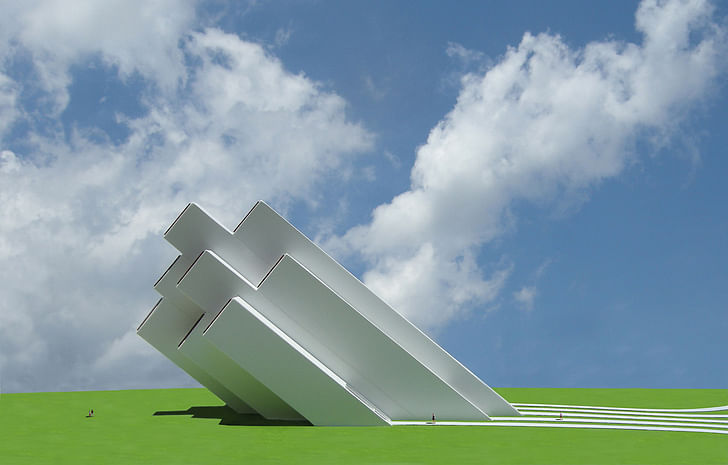

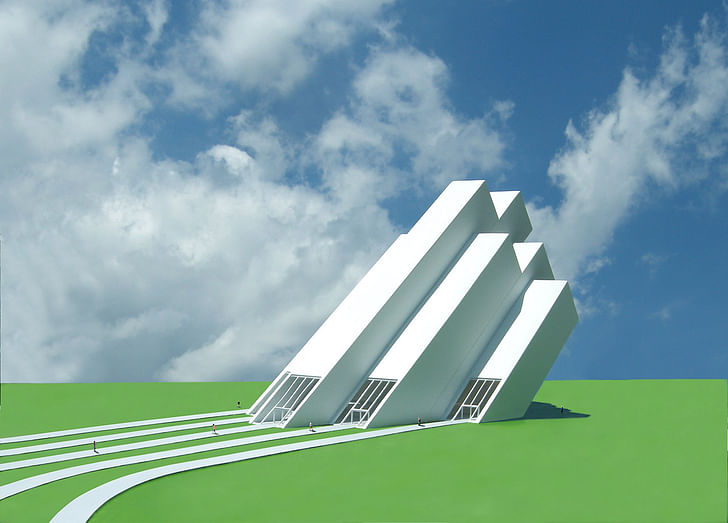

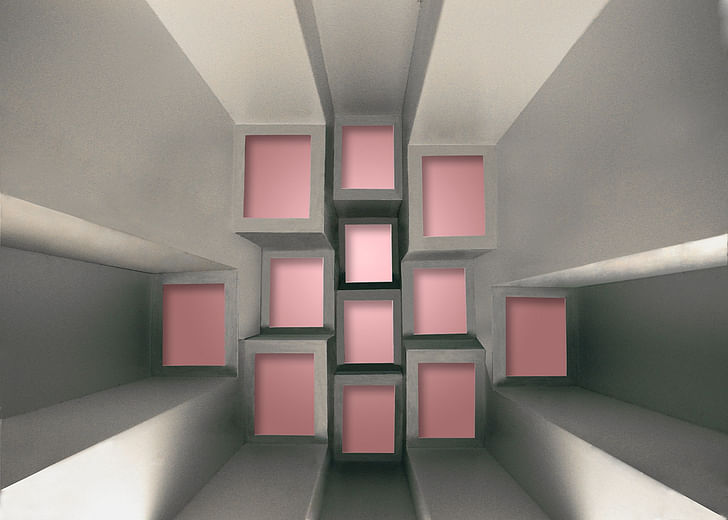

The artist and designer Michael Jantzen has added another structure to the surreal panorama made of his alternative-energy social and living spaces. This latest addition —Sun Rays Pavilion — is an oblique gathering area made of 12 precast concrete columns towering 150 feet tall. The Pavilion’s flat roof, as it were, faces south. Glazed with photovoltaic film, the structure generates its own electricity, with some to spare — providing the local power grid with surplus energy. Large glass sections and doors keep the space ventilated.

As it is with such projects, there are no production plans. Not yet, anyway. Nevertheless, in the fantastical landscape where many of Jantzen’s concepts reside, Sun Rays Pavilion serves its purpose: it is a gathering space, after all, visited in no small part by bloggers and magazine readers; it further broaches exactly those questions and concerns Jantzen hoped it would. Besides, as Jantzen tells me, the fate of a realized structure may be even harder to swallow than that of one confined to paper.

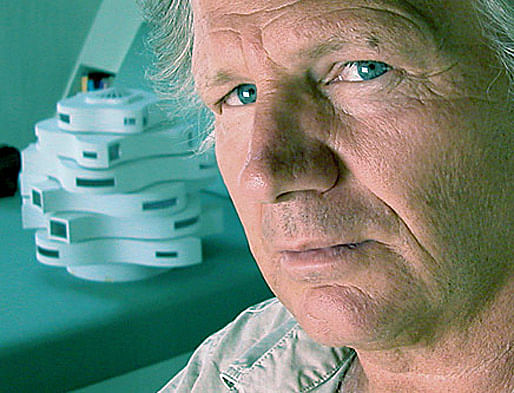

Until recently, Jantzen was based in Los Angeles, but I catch him now, relocated, in the Central Time Zone of St. Louis, MO. Below is the condensed and edited version of our talk about the energy it takes to power a building, and the energy it takes to deal with a home without a home.

Katya Tylevich: I think of your projects in the context of vast, open spaces. St. Louis is a different story, isn’t it?

Michael Jantzen: The city is, which I don’t like. I’m not a city person at all. But the farmland around here is very conducive; the open spaces are quite beautiful, especially this time of year. Really, though, it doesn’t make that much difference to me, unless I’m actually building something physically. Conceptually — mentally — I can project wherever I want. I don’t build very much. [Laughs.] So my surroundings don’t make a lot of difference.

KT: It must be even harder to get things built now. Obvious statement?

MJ: You know, I design these things, and get them out on the Internet and hope someone will come back to me wanting to build. So far, all I seem to get is more press. [Laughs.] Which just leads to more press. Although, I just got hired to do a project. Which I can’t talk about. It’s all top secret.

KT: [Sigh.]

MJ: If it happens, I’ll let you know.

KT: You recently got Sun Rays Pavilion out on the Internet. What is its place among your other designs?

MJ: In the last few years, many of my projects have been looking at how we can create exciting public places — gathering places — that are architecturally interesting but also function. These places are able to gather and, in some cases, store alternative energy from the sun, wind, and so on, then distribute that energy to the community for which that structure is built. So the Sun Rays Pavilion is thinking very specifically about the use of solar energy and the photovoltaic films available now.

With [photovoltaic] applied to glass, you get light through and produce energy at the same time. The whole idea came from seeing mist on fog — the sun coming through and creating shafts of light. The particular shape of this structure came from that, as well as the idea of actually crystallizing those rays of sun coming in. Then the energy is gathered as well and put to use.

I first started using photovoltaic cells in the ’70s to actually power real structures. It’s just a logical thing to do. I mean, it always seemed to me that if a building can produce its own energy —why not? Further, if the hardware that produces energy can become part of the aesthetics, so much the better. As opposed to just taking a conventional house, let’s say, and sticking a panel on it. That’s better than nothing, but I’m trying to highlight these energy gathering and storage systems as an important part of the architecture, or the design, or the art, as opposed to just something that’s an afterthought.

Many of the things I do come from a conceptual kind of starting point, as opposed to my arbitrarily trying to create an interesting shape or something. My work is always going back and forth between the very conceptual and very practical.

KT: Where does the Pavilion fall on that spectrum?

MJ: More toward the “art” end. Its prime function is to create excitement about the use of the sun, to stimulate interest. Obviously, if I wanted to be purely functional about a structure like that, I wouldn’t design it the way I did. I’d just create a big flat surface and face it south, but it wouldn’t be as interesting, necessarily.

I think it’s really important, today, to create excitement about the potential use of alternative energy, and sustainable design in general. That’s being done now, but you know, I started doing this in the early ’70s. There was a lot of resistance, and still is. Ultimately, people want things to look good. [Laughs.] And they’ll suffer a lot if they don’t. Then, of course, you have to define “good” and that’s a whole other thing.

So, part of the intent here, is to say: “See, things can be interesting-looking and exciting, and still do some good for the planet.”

KT: You seem to be creating your own planet — a different world, maybe — with these projects. In your mind, do your works coexist or are they very independent of one another?

MJ: Well, I think, visually most of them are independent, but conceptually they’re very similar. Unless I’m purely doing an art piece… Though, more and more, even the art is taking on alternative energy systems. What’s important to me is that I don’t get stuck in a rut where I’m identified with a particular style and a particular approach.

KT: Someone online criticized Sun Rays Pavilion for sitting in a grass field, instead of a city where it could do more good. Now, if we’re talking about your projects as realized, what kind of environments do you see them inhabiting? Where do dense cities come into play?

MJ: I can see Sun Rays Pavilion — and we’re just talking aesthetically, now — projecting out, between many buildings. I think it could work in that way. Most often, I put these projects in neutral environments just to focus in on the design itself. I let other people think of where the project could be. In some cases, I photograph different kind of landscapes, then PhotoShop structures in, which can be very interesting. But I like the surreal nature of these things. You’re not quite sure where it is. It’s familiar, but not quite.

KT: So what happens to a structure like M-House when it’s actually realized? What’s the fate of that structure, now?

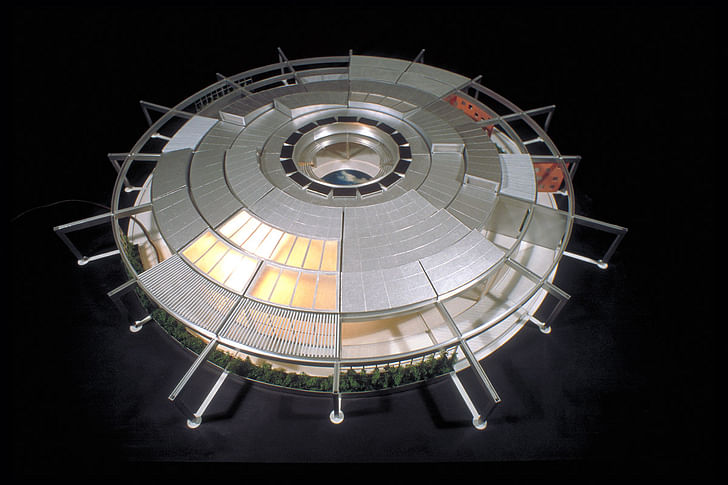

MJ: [Laughs.] Well, it had a really interesting fate. So, I built it myself. (Almost all the projects that have been built, I’ve built myself.) It was 2000, and I built it just north of Los Angeles in the little community of Gorman. The property at that time was pretty cheap, so [my wife and I] bought 20 acres with the intent of building the structure there, then selling it, because it was a prefab system.

Actually, I built most of it in a garage in El Segundo and trucked everything up on the hill in Gorman, put it all together so that it could be taken apart and sold. Meanwhile, [my wife and I] just moved somewhere else, and I hoped to get some press to help sell M-House.

Well I didn’t sell it right away, but it started getting a lot of press. It was in the MoMA show last summer, and Brad Pitt was going to buy it at one point. That fell through because he wanted to put it in Santa Barbara and he was going to have trouble with the Coastal Commission. So then I tried to auction it off to Wright Auction House in Chicago, and that didn’t work, then just about a year ago, I turned it over to Philips de Pury in New York, to try to sell it through private sales. They sold it within a couple of weeks. I have no idea to whom, because it was private sales and they won’t tell me. All I know is it’s a Korean art collector. The plans were to move M-House to Seoul and put it up somewhere, I don’t know where.

Luckily, they paid me. [Laughs.] And they actually even bought the model on display at MoMA. They bought that, then Philips de Pury made arrangements with a moving company in Gardena, CA to come take M-House down. Which they did, under my supervision. The moving company put it all on crates, and into their warehouse in Gardena. That’s where it is today. Whoever bought it, hasn’t been able to come up with the money to pay the mover.

So M-House is sitting in many, many pieces in a warehouse in Gardena. That may be its fate. It may get trashed, because my huge structure is taking up half of this warehouse space.

KT: What do you do, now? Do you say “That’s part of the artwork”?

MJ: Yeah, exactly. It’s been a very tough thing because the market isn’t there, or hasn’t been there, for the kind of things I do. What I’ve been amazed at is how much press I get. For the last two years, I’ve been published somewhere in the world an average of twice a week. You name the country. Press doesn’t pay the rent, but if there’s any hope at all, it’s going to be by getting the word out there. I like the idea of people sharing ideas. This is not just about, you know, an ego trip. I’m really trying to do some good.

Katya Tylevich is a contributing editor for Mark Magazine. Her works appear in Frame Magazine (forthcoming), The Onion A.V. Club, Vice, and Russia! , among others. She recently completed a depressing children's book and founded a doomed arts journal. She writes scripts and short stories.

6 Comments

Great job, Katya. Excited to read more from you!

Cool interview, Katya, congrats. Great Captain's concept ! and amazing projects. M-house like it, uncommon plan and spaces. really interesting.

Great interview. Look forward to more.

It brings up an interesting point. Namely that unlike in most actual instances of alternative energy powered housing where the panels and turbines etc are an afterthought, add-on or appendage, with his houses Jantzen shapes the piece around the concept/power source....

Form follows energy source?

Why St. Louis?

i was actually surprised by that myself brand..

Maybe Katya can elaborate.

Jantzen started out in St. Louis so it is probably a return to roots...I recall seeing him lecture there on his agricultural building-inspired houses in the early '80's, but unfortunately solar energy had fallen from fashion by then.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.