Working out of the Box is a series of features presenting architects who have applied their architecture backgrounds to alternative career paths.

In this installment, we're talking with architectural-theorist of cycling Steven Fleming.

Are you an architect working out of the box? Do you know of someone that has changed careers and has an interesting story to share? If you would like to suggest an (ex-)architect, please send us a message.

Archinect: Where did you study architecture?

Steven Fleming: The University of Newcastle in Australia.

At what point in your life did you decide to pursue architecture?

I used to organize groups of kids to help me "improve" our neighborhood with BMX tracks when I was twelve. Plus I was a compulsive drawer and builder of things, like guinea pig hutches. Architecture came into focus as a career choice thanks to teacher who arranged a school-work experience placement for me in 1983, when I was fifteen. I really enjoyed the irreverence and wit of the young architects in that office. Thirty years on, and it's still the company of architects that I enjoy most about working in this field.

When did you decide to stop pursuing architecture? Why?

I was working as an architect for the Singapore government in the mid-nineties, designing high-rise apartments, very quickly, with a lot of orders from above and not a lot of real discussion among us designers. My team leader made the mistake of taking a group of us to hear Jan Gehl speak at the National University of Singapore. He thrust my mind back to what I'd learned as a student, about Jane Jacobs, Gordon Cullen and Kevin Lynch, and how the urban design field arose in the 50s at Harvard's GSD to give primacy to the pedestrian's apprehension of the city from street level. Well this just wasn't on the Singapore government's agenda—at least not at that time. It became pretty obvious that I would need to do a PhD and get myself into a position where I could influence policy. I was awarded a scholarship from the Australian government on the strength of a proposal I wrote to research the cyclist's apprehension of cities. I could be angry that no academic back then was actually available to supervise a study focused on bikes. I was actually steered toward writing a dissertation about architecture and aesthetic philosophy. But that did lead to ten really enjoyable years establishing myself as an academic, teaching architectural history and theory, and leading design studios.

Describe your current profession.

I'm an architectural academic on a mission to get as many cities as possible to approach their next growth phase with cycling at the forefront of everyone's thinking. The transit oriented development (TOD) model crushes people onto trains and only gives them slow walking for exercise. If urban districts existed that were designed around cycling—and I don't mean an old city like Groningen that was originally for walking and now has lots of bikes—then that bicycle district would give more people more access to more jobs, schools and shops in the time available to them in an average work day, plus it would keep them healthy. Most cities have the space for this right in their midsts, on their disused industrial wastelands.

I'm an architectural academic on a mission to get as many cities as possible to approach their next growth phase with cycling at the forefront I've been on this mission since I started writing a blog filled with all my rumination on architecture and urban design from the standpoint of somebody who has always used bikes for most of their transport. I found lots of cyclists were like me, with cognitive maps of their cities that were based less on roads than former rail corridors and urban waterways. As an architect I was struck by the development potential of the brownfields that hang from these corridors like beads on a string, not as places to drive between and get out and walk, but to ride between, and ride around. Before I knew it I was discussing this idea with NAi Publishers in Rotterdam, and collaborating with a famous bike researcher at Harvard, Anne Lusk, who also has a background in architecture. I did a world tour with a folding bike meeting lots of the big names in bike advocacy, like Mikael Colville-Andersen in Copenhagen, and I haven't stopped traveling and speaking and developing research projects. The latest will culminate in an exhibition inspired by General Motors' Futurama exhibition at the 1939 World's Fair, only instead of whetting everyone’s appetite for owning a car and a house in the suburbs, I want my Utopian vision to open people's eyes to the potential of bikes, if cities were actually built for bikes and other modes weren't allowed to impeded bicycle motion.

What is your experience working with local governments concerning bike-transit initiatives?

Local governments in cities where parking is cheap and the effects of congestion aren't so plain to see, are very different to local governments in cities like New York, London or Sydney. In those big cities, most voters have given up trying to drive, so they elect bike friendly mayors like Bloomberg, Boris Johnson or Clover Moore. The elected officials in the cities I've mostly lived in are about as excited by the prospect of meeting bicycle advocates as they are about meeting people with disabilities or any other minority they're obliged to appease. So yes, I've done quite a lot of advocacy in my back yard, but I'm more concerned to speak to people in any country who want to be leaders in building for bikes.

It's better to speak to city officials who know their city needs cycling, as happened recently in Singapore. You go there, and you get an audience with the folks at the top, and they're all taking notes and engaging in a genuine discourse. They're certainly not paying lip service and thinking of doing as little as possible. Then there are people who really surprise you, like the developers I met in America a few months ago. I thought talking to them about space for bikes inside apartments, to really incentivize riding, would be going too far—that they would only want to bike-wash their project with something like a shower down in the basement. They surprised me as well. But then they're like the government in Singapore: they can see how building for bikes adds up economically in their particular context.

What skills did you gain from architecture school, or working in the architecture industry, that have contributed to your success in your current career?

I'm lucky that my brief time in practice gave me the opportunity to personally design some large projects. So there are sites with buildings, and one with a big park I designed, that I remember first going to and just seeing mud and scrubby vegetation. As someone with that experience, I'm struck by the way community groups and politicians give all their energy to redeeming the established parts of their cities, but are often blind to the fact that the future of their cities depends more on what happens on wastelands. I'm unique Bike transport is the biggest thing in the history of cities since Marinetti's Futurist Manifesto and the machine age among bicycle advocates, that I'm less concerned about cycle tracks running down main shopping streets (which I agree are important), than with getting people excited about a car-free vision for docklands, and gasworks, and abandoned factory sites that will just become big Ikea stores if we can't all be enthused by some more sustainable vision.

The other really important lessons for me came from my architectural history lecturers, and previously my art history teacher at school. I was also fortunate to spend a sabbatical working with a really famous philosopher of historiographical method, Arthur Danto at Columbia. Bike transport is the biggest thing in the history of cities since Marinetti's Futurist Manifesto and the machine age, and I find understanding that history is a huge help when you're working with people who really are bringing about an historical shift.

Do you have an interest in returning to architecture?

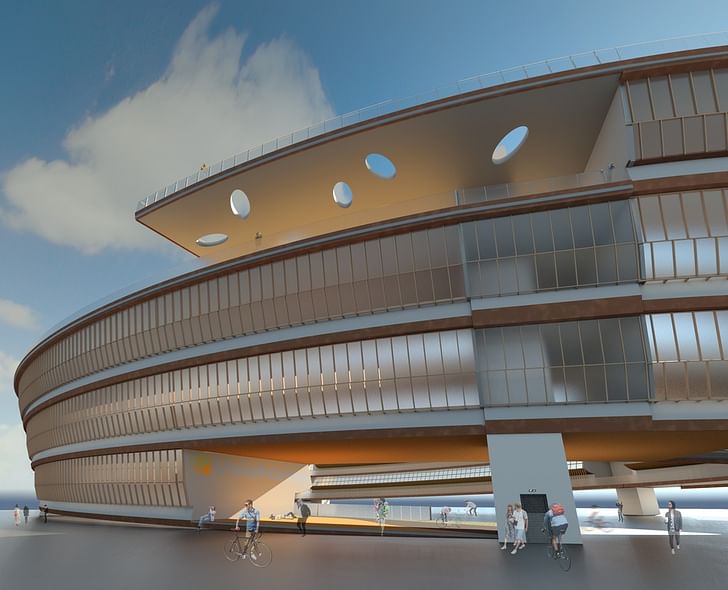

Well, if anyone wants a bicycling city with an undulating ground plane to harness and release cyclists' energy instead of making them brake, and with a whole range of ride-through buildings so no one ever has to dismount, then seriously, give me a call. The time is right, I feel, for a major prototype project that everyone will look to and wonder why we wasted a whole century using external motors for transport, when each of our bodies is a motor itself.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

3 Comments

For me, this type of work is more inspirational than the glossy renderings I see that is all too common in architecture work these days! Seriously, bike friendly movement needs to be in the forefront of cities around the world! Great work, Steven!

be interested to hear Steven Fleming's thoughts on something like this...

I've been delighted to read your site since the launch. Keep up the great work.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.