Starting with an adaptation of Jorg Schlaich’s solar chimney power generators, Behin's project employs the stack effect to moderate the temperature of the city, and to provide for some of its energy needs. Already a successful engineer-entrepreneur when he decided to study architecture, Behin uses his strong understanding of technology to enter the problem of the zero carbon city from a pragmatic point of view, but ends up asking us whether we're ready to re-engage utopia. - Bryan Boyer, Senior Editor - Archinect

Editor's note: It's a familiar claim by now: A lush new city will rise from the super-heated sands of the Gulf, in perfect zero-carbon equilibium. The enticingly difficult technological problem of conquering the uninhabitable desert and the peculiar opportunity to social-engineer new communities has put the Gulf in architectural headlines again and again.

↑ Click image to enlarge

Stack City is situated between the Gulf coast and mountains of the Emirate Ras Al Khaimah. Click on this and all of the images to get a detailed view .

Boyer : Is the "machinistic" in your project entirely cynical? If we built it, what role would the machinistic play?

Behin : Here I would refer to Melvin Kranzberg's first law of technology : "Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral." My intent in this project is neither to celebrate technology, nor to demonize it, but merely to point out that it underlies an emerging form of urbanism, and that it will ultimately be only what we make of it. Technology presents us with a series of choices, with both pitfalls and opportunities. To address them, we require not additional technology, but rather its integration with culture and politics. It is precisely here that I think architecture has a role to play; it can provoke discourse about the ethics which will shape the nature of technology in our future environments. The "machinistic" in Stack City is intended to provide such a provocation.

↑ Click image to enlarge

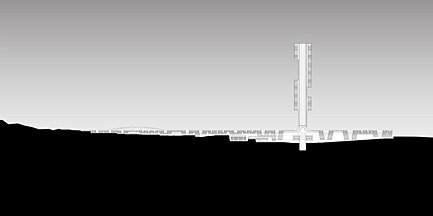

Adopting the Gulf’s tendency towards exuberant iconography, the city’s form isn’t just a representation of sustainable technology – it is sustainable technology.

Boyer : In recent debates about the relationship of contemporary culture and the market there is a persistent thread of suspicion towards earnestness. How do you feel about being earnest in this climate?

Behin : This is a loaded question because terms like "earnest" conjure associations with very specific periods in architectural thought. I think there are many different ways in which to be earnest. Certainly, an outright rehashing of the well-intentioned but doomed utopian projects of the sixties and seventies would be blind to the last few decades of history. On the other hand, faced with the futility of a positive social/cultural/ecological project for architecture, giving up and regressing to an empty cynicism or retreating into formal and stylistic navel-gazing seems to get us nowhere. But I think your question is extremely relevant, and certainly underlies many of the issues we're currently grappling with. I think the answer is to find new ways of being earnest which are, perhaps, more nuanced, and difficult to pin down.

One luxury of an academic project is that the constraints that ground practice in reality can be opportunistically "cherry-picked" and instrumentalized as departure points for speculation. The intent in Stack City is to have a footing in reality by fully embracing, for good or for bad, the phenomenon of new cities in the UAE. With this as the context, once you accept the integration of technology on an urban scale in projects like Norman Foster's Masdar, you can ask what would happen if you take this model to an extreme, and then find an alternative architecture and urbanism within this condition.

↑ Click image to enlarge

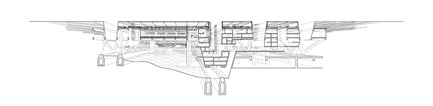

A sectional perspective reveals the different layers of inhabitation that occur within the urban fabric: a top zone supporting air flow associated with the solar chimney along with transportation and energy infrastructure (including photovoltaics), a middle zone containing cellular spaces such as homes and offices, and a bottom zone comprising a continuous ground which is thickened to support large-scale and communal programs.

Boyer : This reminds me of a point that Bruno Latour makes often: that a world of facts has been replaced by one of concerns , where "simple" objects are enmeshed in long chains of decisions that are not immediately obvious. No building without its ideology, no ideology without its material manifestation.

You've mentioned No-Stop City as an analogous example but I'm curious to hear more about your observations of the relationship between humankind and nature in this post "pave the earth" world. Parts of North America are strategically dotted with Home Depots never more than 30 miles apart, so in a way we've achieved a no-stop-home-depot. Not to mention the parallel no-stop-Walmart , no-stop-Best Buy, etc. What is the role of the 'plenum of nature' that sits at the bottom of Stack City?

I don't know if it makes sense to talk about nature as distinct from the man-made any more. Behin : That's very interesting. As I think you point out, I don't know if it makes sense to talk about nature as distinct from the man-made any more. In fact, the bottom layer of Stack City is anything but natural, in the conventional sense, since its temperature is moderated in relation to the actual desert outside. It is a synthetic environment that relies on the technology overhead (the stack-effect updraft system) for climatic tempering. So I don't see the bottom layer as an attempt to preserve a pristine "natural landscape", but rather a hybrid zone that highlights the interdependent relationship between the "natural" and the "man-made".

↑ Click image to enlarge

The top layer supports air flow associated with the solar chimney along with transportation and energy infrastructure (including photovoltaics).

↑ Click image to enlarge

Left: The middle layer of the city contains cellular spaces such as homes and offices. Right: The bottom zone of the city provides a continuous ground which is thickened to support large-scale and communal programs.

Boyer : It almost seems as though the strata of Stack City are to be read as a metaphor of society: not for the organization of individuals, but for the way that we as a culture think about technology. Let's say, it's a gradient of technological acceptance. Is Stack City also stacked (is there a hierarchy real or implied) in your sectional zoning?

Behin : Yes, certainly the "stack" in which I'm interested is not just the solar updraft system (i.e. stack effect) but the sectional stratification that occurs in the city itself. The different strata are meant to articulate a reality which exists in all cities, but is perhaps hidden just underneath the surface of daily experience. Specifically, as you pointed out in a previous discussion, cities are an accumulation of technological infrastructure which enables all the experiences we have in them. I think this is especially true in the "zero-carbon" urban developments that are being proposed today. By articulating this infrastructure as a zone that can itself be occupied, I hope to bring it into the open, and to exploit it architecturally and urbanistically through its relation with the other strata. The experience of daily life in Stack City would involve a series of transitions between these stacked zones.

↑ Click image to enlarge

Overall section

↑ Click image to enlarge

Model with top layer removed to show urban fabric beneath

Boyer : What is "the future?" Is it a utopia, a dream, a call to action? I'm especially curious given that you use "the future" to motivate problem solving that is explicitly aimed towards current-day issues, whereas modernist utopias typically worked more as explicit provocations.

An "ethics of the future" has been replaced by a tendency towards atomization and instant gratification. Behin : For me, it is almost more important that we invoke the future rather than how we do it. The act itself of thinking about the future, whether it is as a utopia, a dystopia, a receptacle for our hopes and fears, or merely a bureaucratic implement of planning, implies that we have a collective responsibility towards a common destiny. Jérôme Bindé of UNESCO writes about this in the context of sustainable development. An "ethics of the future," Bindé warns, has been replaced by a tendency towards atomization and instant gratification. The prevalent economic and political ideology of our time, that of the free market, seems to be partially responsible for the neglect of the future. The future, in this way of looking at the world, is no longer the object of human deliberation and action, but has a way of working itself out as the sum of autonomous self-serving impulses, or as more commonly phrased, through the 'invisible hand' of the market. But markets have a notoriously short-term view, and the problems we face, be they social or ecological, can operate over very long timeframes.

More importantly, abandoning the future as a cultural construct deprives us of a valuable instrument for defining ourselves in the present. You can learn a lot about the ethos of a society by looking at their science fiction. In that sense, the future is a place in our collective imagination, a terrain on which we fight our ideological battles and air out our common neuroses. This is precisely where architecture must play a role. Sustainable architecture shouldn't just be concerned with the tactical level of engineering efficiency and the preservation of resources, but should also participate in the invention of alternative futures in cultural imagination.

That said, I think architecture is in a unique position to be very practical, addressing current-day issues, but to simultaneously work as a provocation (the way, as you point out, modernist utopias operated). In a sense, architecture can be provocative by engaging the banality of current concerns as the reference point for speculation, because by doing so, it can perhaps point out that alternatives exist as latent possibilities within today's realities.

↑ Click image to enlarge

An adaptation of Jorg Schlaich’s solar chimney power generators, Stack City employs the stack effect to moderate the temperature of the city, and to provide for some of its energy needs.

Stack City won the James Templeton Kelley Prize for best thesis or final design project at the Harvard Graduate School of Design this Spring. The project was advised by Professor Hashim Sarkis with technical advice from Professor Matthias Schuler .

Previous to receiving a Master of Architecture from the GSD, Behrang Behin earned a Master of Science from UC Berkeley and a Bachelor of Science from Yale University. He is currently continuing his research on Stack City as an Aga Khan Visiting Fellow at the GSD.

Creative Commons License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License .

/Creative Commons License

6 Comments

So good to see that work can be critical and optimistic at the same time. Well done.

nice interview.

nice job. ben, it's great to see that somebody at harvard invoked the ethics of something.

"all animals are equal, but some are more equal than others."-Squeeler.

I agree with the above comments regarding the balance between critique and optimism.

However, a word about the architecture of the project:

Must a ‘utopian’ project entail a predetermined iconic form that neglects the performative conditions of the site? This project reminds me of the plethora of other idealized utopian projects that plunk themselves down into a context rather like a spaceship. There are so many examples, I doubt I need to highlight any of them.

Would it not be more productive to engage the site and site constraints and conditions as opportunities that inform the design process, thus tailoring and optimizing the system of urban fabric and performative energy generator to begin to think about how it could be built?

In other words, why the idealized circular form? Doesn’t an Ebenezer Howard-esque plan suggest that there is no thought given to the micro-climate of the site? Pervading winds, pressure, direction, topography? Howard never meant for those diagrams to be taken as literal suggestions for spatial solutions, but rather merely relations between different types of uses that might be tailored to any locale, with specificity.

The project proposes a raised plinth, raising most of the occupied program off of the ground plane and merely touching lightly via footings. This would entail a massive amount of concrete, which, as we all know, produces more carbon dioxide in its formation than the entire transportation infrastructure yearly. I thought the thesis of the project was how to mediate ecology [‘nature’] and economy [‘man-made’]? And yet garnering the required building materials would damage ecological conditions?

I don’t mean to sound like I’m harping on the project, because I do find it to be relevant, well considered and beautifully articulated.

Rather, my point is that considering real constraints does not dilute a utopian polemical project, it only makes it stronger. A project that is critical, yet optimistic, as well as architecturally thoughtful is something we should all strive for. Negating, neglecting or ignoring real world architectural conditions and constraints in the academy is hurting the profession in the building industrial because a loss of expertise, and technical proficiency inevitably leads to a loss of responsibility and power. Thus reducing ‘architects’ to passive information managers and aestheticians.

I didn't really read the descriptions or comments previously posted by others but just looked at drawings and read a few captions, believing that the author was successfully able or miserably failed to convey, through these drawings as thoroughly and accurately as possible, his vision of an alternative future or whatever his intentions were.

I am all for 'inventing alternative futures'. I also love these sci-fi quality, hyper-cool images. It would be pretty cool to have them on my living room wall.

However, judging by Behin's vision of the future as articulated here in these drawings, this city looks pretty dead. JPLOURDE seems to suggest or points out the fact that Behin has used a mechanical diagram as 'spatial solutions'. That is the greatest flaw of this project. It looks as if it is from the post-nuclear war era. I also don't think Behin was able to make a convincing case that this is a city for people and not just a power plant. Brining transportation layer up above buildings is interesting but this inversion of typical layering of city with air+transportation zone up in the air is too dominant and suppresses everything else in favor of generating a little bit of energy. If Utopia by definition cannot be realized for practical reasons, at least, shouldn't it show us what we really yearn for in our lives in our cities? What I see here is not only an unrealizable dream but also a pretty depressing one at that.

Shouldn't utopian visions provoke us to embrace rather than to turn away from them? I think this project is successful in provoking us but in my opinion, it ends at that and does not take us any further. To me such an endeavor is meaningless for architecture even for an academic student project. It is only good for museum galleries in the vacuum. What about 'integrating technology into politics and culture'? This kind of vision of integration only turns us away from all the technological possibilities for our 'politics and culture' it tries to promote.

There's also a fine print as a part of this interview that accompanies these drawings and that reads, "it is almost more important that we invoke the future rather than how we do it'. For me, that is such a cop out and renders architecture powerless. In that sense, this project is similar to Jeanne Gang's retractable urban baseball stadium.

I will look forward to the result of Behin's followup research at GSD.

Steven Park, Chicago Architect

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.