Rarely do we allow much thought to seemingly generic labels such as "urban." Outside the cloistered world of architecture, "urban" has become a synonym for "Black and Latino" where it is used to describe things from fashion to music . Facing this reality is the explicit purview of The Office for Metropolitan Alternatives (Office/MA) , a group founded by Paul Goodwin and John Oduroe to investigate how the aesthetics of Black Diasporic culture could influence and inspire architectural form making.

As the director of the Re-Visioning Black Urbanism at the Centre for Urban and Community Research (CUCR) at Goldsmiths College in London, Paul Goodwin explores how multiple modes of 'blackness' engage with the dynamics of contemporary urbanism in the UK. At one of his seminars, Paul met John Oduroe , a young architect in London on a Fulbright Scholarship.

It may appear that their project shares much in common with Teddy Cruz , who draws from the spatial strategies of border communities and shantytowns in order to build a more adaptive architecture. But then - Cruz doesn't exactly brand his research as "Latin urbanism." So is "Black urbanism" just a provocation, or do the spatial resistance strategies of urban black communities differ from other immigrant and diasporic communities?

If "urban" has indeed become a polite synechdote for communities of color, we've allowed this marketing-speak to quietly commodify the black urban experience (talking about cities now). By proposing "black urbanism" as a subject of study, Office/MA forces us to engage the uneasy issues of race, class, and culture.

-- Heather Ring

What is black urbanism?

Paul : From my perspective, black urbanism is a diagnostic tool for understanding 21st century urbanism. Blackness has become a mode of urban subjectivity at this particular global juncture, in a time when hip hop and various forms of black popular culture are very widespread. We're interested in the relationship between various forms urban culture and the production of urban space. The question we are asking is how can this incredible cultural energy—not only hip-hop but also everyday socio-spatial practices—be translated in to spatial form. Black and immigrant communities have and are contributing to the development of cities in the west; this is the space of what I want to call 'Black Urbanism.' Part of what we want to do with Office MA is to look at how the language of black urbanism can be explored through architecture and urban planning.

John : But first we need to ask, "What is the form and function of Black Urbanism; and how do we recognize it when we see or experience it?" We intend to address these questions by exploring the variety of spatial practices that occur within immigrant and minority communities. These practices include but are not limited to the ways in which space, both public and domestic, is occupied and utilized; forms of informal architecture and design; and market activities related to space and property.

Does black urbanism emerge from a place of struggle or resistance? Is it linked to a socio-economic situation, or could black urbanism come from a high rent neighborhood?

Paul: I think historically it has emerged from a place of political struggle, but it has also been appropriated by suburbia. This came home to me recently at a seminar on Black Urbanism we hosted at the ICA. There I described the idea of the "black urban presence" and its relationship to political struggle.

In 1989, I was in Paris and was studying West African immigrants and their role in the housing protest movements. At the centre of those movements were immigrants from Senegal who became politicized through a number of brutal expulsions from gentrified housing in the Eastern part of Paris. In the 20th arrondissement, in the poorer northern poorer part of the city, the expelled families spontaneously congregated in a square and were joined by a number of political squatting groups and created an urban village. They set up tents and refused to move from that village for three or four months. It became a big national media event. They cooked out there, the children played games and it was life in the open air. It was a galvanizing moment and a number of other movements started on the back of these protests, including the Droit Au Logement (DAL) a national homeless movement which is now international.

Droit Au Logement (DAL) protests.

John: They were in a survival mode. And at the risk of romanticizing their circumstances, I believe there's something really intriguing about the look and feel of spaces that are shaped by unconventional and resourceful responses to dire circumstances.

Paul: The dominant mode of understanding what was happening in those movements in Paris was that this was a new form of ghetto. There was a mass panic, because before this the African families were invisible. They weren't living in squats; they were living in special hostels on the edge of the city. But after the expulsions, you would see in the media, African families in Paris wearing traditional clothing in public spaces, which was a jarring experience for many Parisians at the time. I joined some of these protest movements, and remember coming out of the subway to protest outside the mayor's office, and I'll never forget this - an older white French woman looked at us, her face contorted as she screamed, "Savages!" She was very upset by the presence of these Africans, some in traditional dress and carrying babies on their backs. They weren't assimilated or wearing suits and ties. It reminds me of the passage in Fanon's Black Skins / White Masks , where the young boy sees a black person and excitedly tells his mother "Look - a Negro!" . The way that this was portrayed in the press, it was seen as a danger of ghettoization, a new ghetto, a specter of the American ghetto.

And this links to my own work in geography and urban studies, where I was looking at the literature regarding black presence in cities. There's been some constructive and positive work around ghettoization, but nevertheless it's a limiting perspective, because even in its positive mode it posits black presence as a stain on the landscape. The ghetto is a conceived as a non-productive space, a kind of problem, and the black subject is more often than not constructed as a kind of victim, an object to be studied.

A lot of changes occurred as a result those protests, and the image of Paris was changed forever. It helped to create a new space for discussion of multi-culturalism in the city. These protest movements have also had tangible impacts on the spaces of the city. This is a new form of urbanism, and requires a new lens for understanding the black presence in cities.

Black urbanism can be framed as a way of understanding the productive side of the black presence. Now by productive I don't necessarily mean "positive" - it's dialectical and full of contradictions. There is a lot of misery, a lot of problems with 'ghetto pathologies', I'm not denying that. But the other side of that dialectic is a more positive, creative and life affirming energy that is a product of the same disadvantage and marginality. These two phenomenons cannot exist without each other.

What does black urbanism look like?

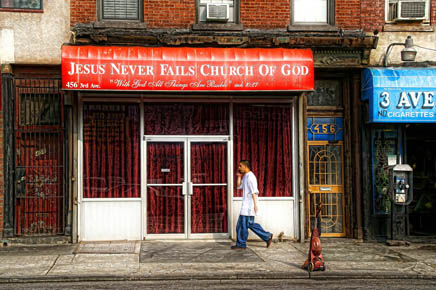

John: Answering this question is the challenge. I think the first step is realizing there's not going to be any kind of singular overriding aesthetic style or form that encapsulates the whole of blackness, since blackness of course is not a monolithic culture formation. Each place, each locale, each practice or activity must be read as unique and contingent upon specific economic, social, cultural, and environmental circumstances. We hope to mass a body of these descriptions and images that collectively begin to suggest other ways of existing within the city. These representations might be interpreted as undesirable to some, but for an increasing number of people, they represent a means of survival. I've been really interested, for example, in the storefront churches phenomenon: that is when religious communities desiring a worship space avoid the steep cost of developing a new building project, and resort to occupying existing vacant structures. Often these spaces come in the form of unwanted retail or industrial spaces that have effectively been deemed undesirable by the market. I am interested in how these spaces are acquired and the ways in which they are altered by these communities to communicate a sense of place and identity. I'm also interested how the presence of these spaces are perceived by the greater public; and the ways in which they and their constituents engage with and alter the streetscape in many communities. This is just one expression of Black Urbanism.

So if black urbanism emerges through modes of resistance or survival, are you thinking this is also something an architect might purposefully implement?

John: I think historically this kind of 'design practice' is something that has happened on the everyday-life level. This project would like to engage with the possibility that these solutions might be able to influence the way architects and urbanists think about mainstream spaces. For example, can these kinds of practices give us some indication about the kinds of spaces and places we should be programming and developing for cities as they continue to grow to accommodate new populations with new needs and expectations. We are trying to stimulate a discourse which will move these things that are usually dismissed as survival techniques of the marginalized or the lower classes and closer to the 'centre' of our understandings of how cities look and function.

Paul: I think a good example of that is New Orleans. Here you have, in peacetime in the United States, a city that's been entirely wiped out by natural disaster and there's now a chance to rebuild it. And what's interesting about this city is that the population was 70% black before the hurricane, and the city itself is based very much on the fusion of cultures, of which black culture is a very strong part of it. So the question remains, how are we going to rebuild New Orleans? What models are going to be used to reconstruct the city? Now a number of jazz artists, bluesmen and creative people have been contributing to this process. There's a recognition that this city was built on jazz and blues and the aesthetics, dynamics and rhythm of that needs to somehow be fed into the rebuilding process. That in a way is a form of 'Black Urbanism.'

John: I was just reading an article about Marc Ecko , the 'hip-hop' fashion designer and the retail empire he started in his parent's basement. According to the writer, Ecko's background in tagging and graffiti gave him the inspiration to begin painting and tagging his existing clothing as a means to express himself. This approach to design is at the root of hip hop culture which prides itself on re-appropriating the familiar and common place and 'flipping' it into something new and original. You can see the same kind of intention in early Punk culture, as well as other forms of culture that emerged from the margins of society. I think that this kind of 'interventionist' approach to cultural production -i.e. understanding what already exists, and then asking how it might be taken further or reactivated in a novel way—makes a lot of sense when considering the way that cities are changing. As new populations arrive into areas of the city previously considered ghetto or off-limits, does this strategy start to suggests a way of understanding how form, space and infrastructure has been and will be transformed in the not so distant future?

Paul: Black urbanism is not an end-product — it's not a fixed thing that you can pinpoint, it's a process. And that process includes, as you say, historical struggle by black communities — and when I say black communities — it's not a fixed ethnic group, though I do recognize the role of African diasporic communities in the production of the concept. It ranges from, on one hand, these historic political struggles, and the other, to more popular cultural tropes coming out of hip-hop, jazz and popular culture.

Are you concerned that your research might contribute to the commodification of black culture?

Paul: I think you're right, this is entirely possible. Black culture is already being commodified , so by introducing it to architecture and urbanism, there's a danger of that. David Adjaye is an interesting case study. He's been considered around the world as a great architect - which I think he is. But some comment that his novelty is his blackness, his otherness. I think that would be a limiting way of understanding what he does. There's a danger in black urbanism - a danger of naming the process, which I think you're question implies, that you can fetishize it and contribute to its commodification. And I think that's something we need to think about.

Even at the risk of commodification I think it's still important to debate the issues that 'Black Urbanism' raises. Even the name -- people say to me, "Why do you use the name 'black urbanism'? Why don't you just call it 'different urbanism' or 'diverse urbanism' or 'cultural urbanism'?" And I think, again, it's a legitimate question, as black urbanism can lead to a lot of misunderstandings. But I think it opens up a space for debate. It's deliberately kind of provocative. "Black" and "Urbanism"? What do the two have to do with one another? And that's exactly what I'm trying to get at. Because when I read the architectural magazines in architecture - I don't see much blackness. I see whiteness. Literally. I don't see much that is representative of what we're talking about - and I'm not just talking about David Adjaye --

But let's talk about David Adjaye. Do you feel his work expresses something about blackness? Is there an aspect of black urbanism that distinguishes the buildings of David Adjaye from the work of - say — David Chipperfield?

John: I think he has a very sophisticated way of addressing blackness and the idea of how cultural difference might relate to design. If you look at his recent monograph on public buildings, Adjaye draws a conceptual connection between the formal aesthetics of each of his projects and specific cultural artifacts gathered from various places in Africa. As you can imagine, the artifact is one but several influences helping to determine the final form of the building. The projects stand as pieces of architecture. He doesn't go at length to force a connection to the original artifact in order to justify his design. Similarly, I see the IDEA store as a response to the question of "What can I learn from the complexity of street level activity along Whitechapel High Street, and can I translate this experience into a building?" I really think he is thinking about forms of black urbanism. Whether he would call it that - I don't know.

David Adjaye's Idea Store, Whitechapel, London.

Paul: A big part of David Adjaye's work is this idea of publicness, and opening up the idea of publicness to new and broader understandings. But I think as observers of his work, we need to be careful of a trap - the trap of literalism. I don't think John and I are interested in a literal kind of application of black culture to urbanism, that's not the point. So if you draw on these influences and then make a kind of "black architecture," or a kind of "African architecture," that would really be a closed typology. Black urbanism forms a kind of logic that might lead to an inspiration or design, but it's just one of a number of palettes or textures that are important to the process.

What about the landscape architect, Walter Hood - who lives and works in West Oakland?

John: Walter did a workshop at Carnegie Melon University while I was a student. The thing about Walter Hood that really impressed me - and he's been an influence of mine for a long time now -- is that he spoke of visiting communities where he was commissioned to work, asking "What do you want," and engaging with them to develop a process to realize their desires. Instead of just saying, "Thank you," rolling up the trace and leaving to formulate his own designs, he would take them seriously and undertake the difficult task of interpreting sometimes fragmented and contradictory requests and translating them into coherent spaces and forms. This has inspired one of the goals of Office MA, which is to rethink the relationship between public consultation and design. There are many difficulties with the dominant models now used: how do we gather diverse and engaged cross section of a local community? How do we gather information, determine what is important and significant, and synthesis it a coherent design, how do we accommodate the needs and desires of a community when they might conflict with the interests of the client. I got the sense that Walter really tries to engage with these questions in his work. Public consultation is not just a way to assess and deflect potential criticisms—he really wants to understand how we involve other voices.

There is an underrepresentation of black students in architecture schools.

John: During my last year of architecture school, I was flipping through an architecture magazine and saw a picture of David Adjaye. I believe he had just finished the Dirty House in Shoreditch. I stopped for a second and thought, this is the first time I've ever seen a picture of a black architect in a magazine. I think the shortage of role models to inspire young minority students definitely impacts what they perceive as possible or even reasonable career routes. I'm sure there are a host of other factors at play as well. Many highly motivated minority kids feel pressure from family members and mentors to pursue more lucrative fields. I've also witnessed many young minority students leave architecture school after complaining that their ideas weren't well received or understood by older, and quite often, white male instructors. Perhaps there is a failure on the part of the student to translate their lived experiences, into forms that can be critiqued on more ostensibly universal terms. Or, perhaps there is a failure on the part of many educators to acknowledge their own cultural subjectivities, as well as the ethnic, cultural and class subjectivities that have shaped the formation of 'Architecture' as an academic discourse. I don't know, but it makes me wonder how we might bridge the gap between these two sometimes contradictory understandings of what makes for good spaces and places.

John Oduroe's student project translating breakdancing.

I think this issue resonates with bigger questions that constantly on the arch and design agenda: "What do we do after modernism? What will emerge next?" People have been trying to figure this out at least since Venturi in the 70s. I think we'll see some very interesting and compelling contributions to this debate as more blacks and minorities enter into and graduate from architecture schools around the world.

Paul: We've moved to postmodernism prematurely, and paradoxically, postmodernism turned out to be a pastiche form of nostalgia. So, in a way 'Black Urbanism' can be a part of the process of understanding what comes after modernism. Why is Rem Koolhaas interested in Lagos, Nigeria? The Project on the City at Harvard has studied China, the River Delta, Shopping, the Roman City. Why Lagos? Some say he has a romantic idea of Lagos's Urbanism; that there is a logic in what in many ways is actually chaos. And he's sort of been ridiculed for flying over Lagos with a helicopter and not really understanding what's going on at the ground level. Well, I think his engagement with an African city is quite interesting — because what he's saying is: In order to understand future of western urbanism, we need to also look outside of the West and that includes African. We can learn from Las Vegas, but we can also learn from Lagos.

During the Salon that you hosted with This is Not a Gateway, one of the invited speakers was from The Greater London Authority / Design for London talking about regeneration projects in Dalston and Brixton. During the talk, these projects were framed in a positive and uncritical light, but I know many consider these regeneration schemes to be signs of gentrification — and the spaces sterile and generic. What do you think of those projects? Do you think they are successful examples of black urbanism?

Paul: Part of the problem in architecture and regeneration schemes is that issues of difference are dealt with in public consultation, outside of the design process. But what those projects show us is the challenge of dealing with the politically contentious questions of black urbanism within a public policy context. It's very difficult to do that, particularly in England or Europe, where notions of blackness are still relegated to the margins and are seen as regressive and ethnic. I think, to be fair to David Ubaka who presented these projects on the night, understands the issues being raised by Black Urbanism, although as someone who works in a public office, he might be uncomfortable with the title "black urbanism." Arguably, David Adjaye might also have a problem with the idea of "black architecture" or 'black urbanism." It's a diagnostic tool, a blunt instrument to open up debate, but it's not the end product. I don't want us to be talking about black urbanism in 25 years time. I want to talk be talking about an evolved form of urbanism.

Creative Commons License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License .

/Creative Commons License

7 Comments

This entre little article is Bullshit!!!!!

Why is it that white "mainstream"America can't accept the fact that African Americans are creative people? African Americans come from a culture and civilization that pre-dates European culture. Why are people sudying and analyzing the ghetto, a place that no one would like to live in? If a black people lived in the affluent suburbs of white America do really think we would lose our sense of creativity?

The fact of the matter is that all people on the face of the earth posses a sense of creativity weather it's born out of poverty or wealth.

the real subject of study should be what motivates people to create and the manner and process that they undertake to acheive their sense of creativity.

Big up for this interview in its attempt to resolve important questions about the significance of phenomena that is normally dismissed as too banal or unsavory for serious consideration, architectrually speaking. Also, big up to the interviewees for recognizing they're walking a difficult line btwn trying to understand these phenomena and contributing to the 'commodification' problem facing ethnically biased cultural perspectives.

But the irony here is all too palpable. in an effort to help, i'm compelled to point out that the interviewees' concern about the racist dismissal of Mr. Adjaye's professional accomplishments seems to form the foundation of their own work. check it:

"Black" and "Urbanism"? What do the two have to do with one another? And that's exactly what I'm trying to get at. Because when I read the architectural magazines in architecture - I don't see much blackness. I see whiteness. Literally. I don't see much that is representative of what we're talking about - and I'm not just talking about David Adjaye --

oops. hey guys - gonna have to drop your own unqualified prejudices if you're gonna move the 'black urbanism' thing forward. or at least restrain yourselves from airing them out in the same interview.

we know, under the current calculations, soon the 2/3 of the world population is going to be living in urban environments.

majority of this two/thirds would be, the existing low income city dwellers and the relocated and formerly rural members of the population. there would be immigration to the cities for many reasons, mainly for employment and for survival.

as they are not coming with fat wallets to purchase slick apartments and architect designed art collector condos, they will be modifying and adopting most of the existing systems and housing, sort of take them over.

if you are going to coin 'black urbanism,' you might as well add to it that 'we are all black' at that point, in the near future, at least for most people.

the changing urban social infrastructure and physical environment will not be confined to blacks, muslims, indians, far easterns, south americans, african.., 'neighborhoods.' it will expand greatly outside of the 'fringes' ('fringes' via mike davis, planet of slums.)

as they are also called, 'slums,' will be the main part of the physical environment.

this is a projected picture based on statistical information and existing trends.

on the contrary, the description 'interesting,' would be applied to few remaining enclaves where shrunken urban upper class would be living behind isolation and decaying luxury residences of times past, with a lot of security apparatus of course.

i can understand and live welcomingly with heather ring's selection of the cover photograph.

get ready, what you see in that picture will be coming to your neighborhood too. and, it might not be a bad thing, if you understand, adopt and be a part of that economy and culture. or, as an architect, planner; work with it.

it won't be easy, as you can tell from the recent surge of nimby'ism all over the map.

but eventually that picture will be very familiar with slightly different variations and local colors and against all 'past demographics.'

that is probably why many architects and urban thinkers are looking at that these days.

it is the picture of the near future.

and, that future will not be the floating cities, neatly stacked expensive glass boxes, dubai hotels, palm islands, air conditioned cities, and blobby opera house envies.

in the near future, form would be more of a 'mental' construction and superior to plastic manifestations of it, at first. after that, it might go full circle again, maybe.

there would probably a lot of customizations of the manufactured objects and adoptive reuse ideas via necessity.

masses in cities would have different priorities than neatly designed

buildings, cartesian organizations and formal expressions, as we know presently.

urgent needs would trump the escapist and racially homogenous sci-fi.

the future buildings might be low tech, handmade and erected overnight... at least until the population increase, income distribution, food production, political volatilities and other issues are stabilized, if ever.

i find this article very provocative, if we can move beyond adjaye, et al. he is a prolific architect like many of his colleagues and i do fail to see anything particularly african in his buildings anyway.

My main issue with this idea of black urbanism is it's ambiguity.

In my mind it clearly relates (in the form of a label) to a form of identity, or even identity politics.

However, they seem to resist the defining of their term "black urbanism".

It doesn't seem as if there is anything particularly "black" about what they discussed here. If all they are referring to is a non white (majority) urbanism, then the use of "black" seems to be more connected to minority than the black=urban/Out of Africa formulation outlined earlier in the discussion. I think that it would be more interesting to actually dissect what is meant by black urbanism (specifically) as black (African-American, British-African) whatever than to simply be "non-white". In this context Adjaye's examination of the African connections to public space and definitions of space/openness, that his work has drawn on or pointed to is not about "black urbanism" as such. Rather it is about historical connection et al.

The work discussed doesn't in my mind relate too much to the work of Teddy Cruz and others, who seem to be more focused on informality and understanding of non-hierarchal forms of urbanism/construction/design than an actual urbanism of identity.

Informal urbanism does not in my mind equal black urbanism. It is more about an economic condition/situation that an identity..

I would be interested in seeing what a black urbanism as identity urbanism looked like though...

Having also just read one of the essays available from the included links

(see http://thisisnotagateway.squarespace.com/salon-archive/TINAG%20Re-Visioning%20Black%20Urbanism%20Salon%20PRESS.pdf )

I guess i go back to my point why the term "black" if they are in fact interested in broader multi-cultural, globalized cultural discourse, and bottom up design and not just interested in urbanism of the African Diaspora??

I think urbanism of the African diaspora would be more interesting than simply seeking to interpret blackness as an expanded field beyond ethnicity.

Further in the reading they seem to continue to vacillate between reading blackness as a signifier of identity while at the same time trying to argue that it isn't about identity but difference of whatever sort.

there are too many loosely connected phenomena being discussed here, which can be a good thing because the complexity can branch off to many different more refined academic disciplines. i don't know what sort of urban ghettoes breathe the air in europe, but i am more aware of ghettoes of cities in the states. from the title, i assumed that the research being conducted is specific to black people, but as i read the passage, it is not necessarily about them but in a rather insulting manner, about minorities in general since now all the different ethnic groups from their own indigenous cultures are grouped within the blackness. if all the cultural phenomena in urban settings in rich western countries, which have been analyzed since industrialization, had been considered, we would have been dealing with finer points of urbanism, even in relation to other artistic media such as film noir, jazz, beat generation and so forth. i think it might be because it is an interview, not a research paper, but at the same time, it might be a poor age-old attempt to understand geopolitical state of the world with a bias of scientific formalist approach, in which case, we would have much more to learn from cistercian monks' way of thinking and writing. after all, those monasteries were built in valleys full of vaporous gases, in buffer zones between warring lords. if we were to consider the issue of identities expressed through architectural forms, not necessarily urbanism, that could be an interesting research within the context of ghettoes of cities because all the minority communities would wish to have places for their own rituals. i don't know if any architectural designers would not be fascinated with challenges of trying to resolve the conflicts between vernacular forms and modernist aesthetics. however, if the research were to be carried out in the scale of urbanism, i think we would be dealing with too much politics and economy for the discussions to be architectural as pointed out in the interview. nonetheless, conceptually, it might be necessary. if the research were to be conducted in the scale of globalism, i would be a joker.

This in interesting. I am a Black female architect.On of the few that will have triple degree in architecture (B.S in Arch, M.Arch, and hopefully so to be PhD in arch),

I really liked Koolhaas take on Lagos, Nigeria urbanism as a city without colonial ties and not inheriting any overarching European context.

On one note, to me Black and African are not the same thing. "Blackness" to me is a decedent of African slaves in the American South."Africaness" is a person decedent from African continent. Can a person be Black and African-American? Yes. But can a person be African-American and NOT Black? Yes again.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.