Working out of the Box is a series of features presenting architects who have applied their architecture backgrounds to alternative career paths.

Are you an architect working out of the box? Do you know of someone that has changed careers and has an interesting story to share? If you would like to suggest an (ex-)architect, please send us a message.

Archinect: Where did you study architecture?

Gong Szeto:

I received my B.Arch from the University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture and Planning in 1991, a very pragmatic well-rounded program, studying in the wild and woolly late 80’s. To give context, Eisenmann, Tschumi, and Morphosis were hot, Graves and his post-modernist cohort were not. I was personally a Corb, Kahn, Ando devotee, with a secret desire to be the offspring of a Lebbeus Woods and Buckminster Fuller tryst, if you are brave enough to imagine that. My work was conventional and weird at the same time, drawing heavily from the early Pamphlet Architecture series, which was just getting off the ground then.

At what point in your life did you decide to pursue architecture?

My whole life I wanted to be an astronaut or an artist, but because my math skills sucked and so did my eyesight, becoming an astronaut was out of the question. I started college in the Art Department at UT Austin, but only lasted one year there. I attended the senior show in 1986 when scatological art was all the rage, and left the building completely grossed out at the stench of all the senior student paintings made with human feces. I can’t even remember what their big “statements” were all about because it was just too much for me. After a long walk across campus, I ended up in the architecture building where they had their senior show. I remember seeing all the models and drawings, being drawn especially to things that looked more like abstract art than buildings per se, and told myself, “Hey, I can do this.” So I decided to change my major at that very moment. It wasn’t so much I wanted to build buildings, but I wanted to build those MODELS!

When did you decide to stop pursuing architecture? Why?

I officially stopped pursuing architecture in 1995 after working for a few years as a junior architect for Charles Moore in Austin and Leers Weinzapfel in Boston. I was always interested in technology, having learned to program computers at a young age, hacking the Apple II+ and TRS-80 my brother and I had growing up.

My brother Nam, a Cooper Union art and architecture grad, started a new company in New York City doing all things digital. His computer graphics and animation expertise he learned at Cooper proved invaluable in a number of freelance gigs he and his other Cooper partners got designing environments for 3D games, CD-ROMS, prototypes for all kinds of interactive applications.

I left Boston after a failed relationship and moved to New York to figure out my life, in effect, to start over. Nam hired me as i/o 360 digital design’s first employee; I was really a glorified gopher since it took me a while to learn all the tools and techniques they had already mastered at Cooper Union. It was a study in contrasts: the practice of architecture was dreary and mundane compared to the excitement and optimism of pioneering a new medium. I later became a partner and was instrumental in shifting our focus to the web. We quickly became recognized for our work in this new medium, our highest moment being recognized as one of the I.D. 40 in I.D. Magazine. It wasn’t all corporate, though. i/o 360 also developed a reputation in the digital art and conceptual art worlds, showing in New York galleries, and lecturing worldwide on our studio’s experiments. We also did a fair amount of cutting-edge work in the interactive television space, and was even awarded a patent in this area.

Our design firm grew about 25 people with about $3MM in revenue with Fortune 500 clients. We sold the company in 1998 to a publicly traded Internet services company with offices all over the world. It was then that I began working on projects for Wall Street and stepped fully into the world of finance, the engine that runs just about everything we know.

Describe your current profession.

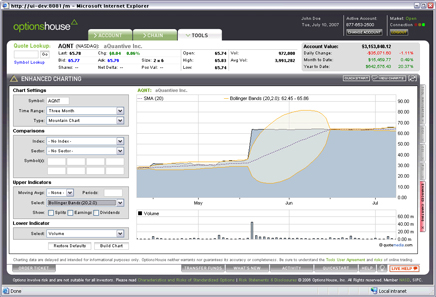

Currently, I design high-performance securities and derivatives trading software for online retail investors and active traders where hundreds of millions of dollars worth of transactions flow through my designs every business day hitting all the major US stock exchanges. I work for a very successful proprietary equity options trading firm and hedge fund as the Director of Design, and in my time there, have launched a brand new retail equity options brokerage and am about to launch a new social community platform geared towards novice investors. I work with very large, real-time data sets everyday, and in the financial space, the data is huge and changing all the time. The responsibilities are fairly huge, as a dropped trade could mean a multi-million dollar loss for one of our customers, and that actually does keep me up at night.

During my tenure as a partner in at i/o 360, one of the first design firms to specialize in new media and digital design, we were exposed to the power of the Internet as a viable communication and transactional infrastructure, and built some of the very first websites and e-commerce applications. After we sold our firm to the publicly traded Internet services company, I cut my teeth in doing projects for Wall Street investment banks, private equity firms and a few venture capital firms. Since then I have been very interested in the financial space, in money, in macro- and microeconomics, in high-performance networked software applications. What I have learned is less about architecture (buildings) per se, but about the architecture of Capitalism itself. This is an area of endless fascination for me. Being part of this world has led to a knowledge base and set of experiences that is probably rare for a designer, and I hope to someday share it in a meaningful way with others.

I also have had a side business in real estate development with my brother, as we value the risks of entrepreneurialism, and are continually interested in the role of good design as a means to sustainable business ventures.

What skills did you gain from architecture school, or working in the architecture industry, that have contributed to your success in your current career?

I most certainly use a lot of the skills I learned in architecture school – everything from ways of thinking about a problem, being able to separate form from function, structured and systems thinking, economy of means, the list goes on. I would say that I have quoted Vitruvius’ “Firmness, commodity, and delight” in more than 50 or so meetings with software engineers, investment bankers, traders, people who have no idea who Vitruvius was and would have no reason to know. But they seem to get it, that a good “anything” needs all three, as I work in an industry that only does 2 of those virtues well (firmness and commodity).

I also catch myself drawing parti diagrams at the beginning of projects and no one seems to know what the hell I am doing since they mostly know the “program” part of the equation. I simply explain it as I am seeking some kind of organizing principle to net out all the competing priorities on the very complex projects I work on, and they seem to understand that. They just don’t really understand why I frequently draw a single straight line (spine) with boxes that grow off it. It certainly doesn’t look like a flow-diagram or a use-case diagram. I really just draw the same diagram over and over again, but in this case for software and not a floor plan…hence the power of the parti. Without it there would be very expensive chaos.

I am also a very good presenter. All those nerve-wracking final critiques in architecture school were worth something pretty valuable in the real world. Sometimes the merits of the design just aren’t enough. You have to sell it and sell it convincingly to bring it to fruition, especially when someone else is paying for it.

In the end, I owe a strong sense of ethics from my education as an architect. Architects truly value integrity – integrity of form, integrity of execution, integrity of conviction in problem-solving, integrity in the rigor of process. Architects believe in the honesty of materials, they believe in the basic goodness of Man, they believe in the power of design to shape human behavior (for good and bad). And I feel architecture truly is one of the most ethical professions – you just don’t read headlines about architects going to jail for cheating and lying.

Do you have an interest in returning to architecture?

Yes, but not as a career. I have some gorgeous land near Abiquiu, NM (Georgia O’Keefe country) that I would like to build on someday, so I will probably put my architect’s hat on then. But that would just be for me and my family and not a client.

8 Comments

first the new architect turned graphic designer student blog, then this series!? are you trying to tell me something, archinect?

Very interesting feature....

The relationship between architecture what he studied, and the spatial/data design what he does for a profession now i find suggestive.

I've always wondered who would take on such an intense project. ------------- Also, kudos to Archinect for this feature. Great insight.

fan-diddi-ly-tastic. bravo archinect.

good article on the utilization of the architecture design program in everyday life. i think Wall Street is "part-of-the-problem." yes, architecture invites discursive, critical thinking but to a certain extent only within the boundaries of the mainstream. the lifestyle of architects (expendable incomes, flexible working hours) should invite further study of the context of not only architecture but society; Mr. Gong seems to understand to some extent the institutions he's working for and their failings but like many design institutions (archinect.com) don't expound upon social issues that are becoming more pertinent in our globalizing world. Lebbeus Woods and Peter Cook seemed to allude to that in the archinect interviews: arch schools are becoming focused on educating for a codified design industry and weeding out supplemental theoretical and, further, social considerations. the ease with which a person working in this industry at such a young age can start an international architecture/design website (archinect) is perhaps evidence that it is not comprehensive enough. it is said that capitalism fragments people; designers should focus just on design or accountants need not worry about things outside the ledger. we are not critical enough because we are fragmented. who can question us if they are not within our group? to some extent the answer is, "no one" because they are in their own. within the american system the only juncture most architects and designers are asked to question themselves is where their world overlaps with the consumers'. though sometimes considered an authority, designers have (increasingly) less to do with art than consumption; and they are conflated.

To my main man, ManfriedMann,

Art and consumption has never been conflated...they are married, happily married.

@ Mike,

even that marriage has given us an idea about how people experience art but my claim, on that point, is something like: design is artistic practice embedded in consumption. 'practicing' and experiencing art are clearly different. moreover, experiencing art and consumption have no natural connection to each other. society loads art with meaning - which i think gives it a richness - but no ethical person can say that where art is imbued with meaning from the unhealthy parts of an unhealthy society is it worth anything but satire.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.