With little care or tact we keep expanding our cities and replacing what was once wilderness with pathetic shrubs in the medians between three car lane avenues. Because we love nature, we put small planters in front of big box stores in the concrete seas that are our suburbs, in what amounts to a desperate effort to humanize the landscape. We love nature so much that we romanticize it, using its image to sell SUVs that in ads, climb idyllic mountains, but in reality are uncritically driven through the increasingly bland (visually and culturally) landscape of sprawl. These are among the arguments laid out to a full Piper Auditorium at Harvard's Graduate School of Design (GSD) by landscape architect Martha Schwartz. She concludes that this Quick, Cheap, and (token) Green view of landscape is an increasing problem in the United States and the world. Martha finishes this section of her lecture with a haunting question: What are the long-term effects of a bland landscape on a society and each of its members?

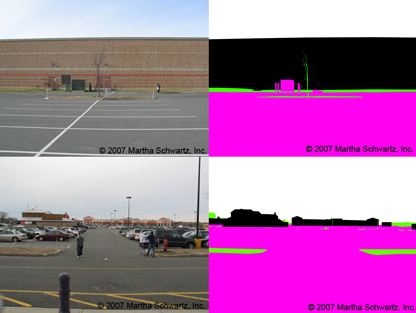

Martha Schwartz and her office developed an analytic series to study the visual stimuli in the suburban landscape, and the role that the architectural object plays in that landscape. In the images we are confronted with the nothingness of the suburban landscape, a sea of gray with token pieces of green. Image Courtesy of Martha Schwartz, Inc.

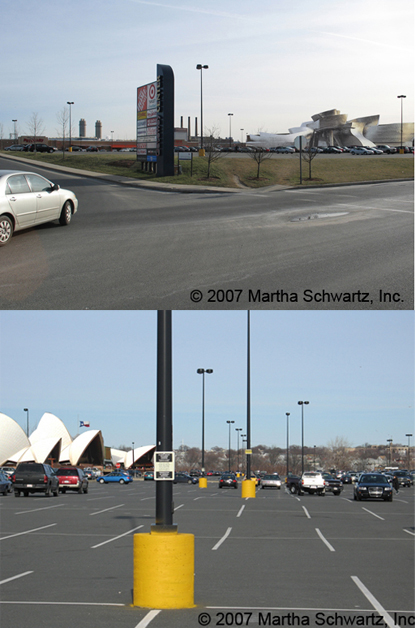

On the other hand the architecture in the glossies disappears in the homogeneous American suburban landscape and becomes indistinguishable from a Best Buy or Target. Image Courtesy of Martha Schwartz, Inc.

For Schwartz asking the tough questions is nothing new. She has made a career of designs that critically engage their environments, not shying away from using artificial materials and new technologies to create spaces that go beyond the commonly understood role of landscape. Most recently, however, Schwartz has found herself asking the tough questions of the design academia and profession in regards to the fair and equal treatment of women. With her January 12th resignation letter to the Dean of the GSD (which was later withdrawn), Schwartz has brought light to a topic that is too often ignored.

Two days after the GSD lecture Schwartz addressed an event sponsored by the GSD student group Women in Design (WiD) on some of the issues that women encounter in the design field. Schwartz told the crowd of mostly women that the most essential problem they face is how to be taken seriously as designers, meaning people of will, conviction, and a well-defined sense of self, in a world that sees those qualities as opposite to femininity. She further encouraged women in design to assert themselves while not losing the sense of who they are and their unique experiences as women. Schwartz explained that, for example, her children and family are very important and that even more than quality time she wants to have quantity time with them. To that end she has developed an office that supports families, allowing employees to bring their children and nannies to the workplace. Reiterating how important it is to think about children and other challenges they may face as women designers, Schwartz encouraged the group to rethink and challenge the professional practice, which according to her still does not reflect the increasing amount of women entering the field.

Swiss Re Headquarters Landscape, Munich, Germany. Martha Schwartz, Inc. 2002. Images by Myrzik/Jarisch.

I had a chance to meet with Schwartz after the WiD meeting to talk about her design practice and theoretical work as well as some of the gender equality issues she brought up during the WiD meeting. The issues at first glance seem very different, but at the core they are both about critical engagement that leads to action in the one hand in the built environment and in the other on the very structure of the design profession. Below is a transcript of that conversation:

Quilian Riano: I know that you would prefer to not talk too much about your January 12th letter of resignation from the GSD.

Martha Schwartz: Yes, that is just not worth talking about too much, we are on track again. I can see that there are possibilities to stay within the department of landscape architecture at the GSD to make it a more conductive workplace for women. All I am asking is for the chance to be able to continue to work and change things.

QR: In the early 90's when you first came to the GSD you were offered a full-time tenure-track teaching position that would have led to the end of your practice. Why did you decline that position?

MS: Because I am first and foremost a practitioner. Don't get me wrong - I am also passionate about teaching, but I want to build landscapes, not just talk about them. I also think that the students benefit, as it is especially important for women in school to have a female practicing-designer as part of their faculty.

QR: What do you think was the fallout of your resignation not only in academia but also in the professional world?

MS: I am happy that there is a renewed discussion of gender in the design fields. I just hope that this conversation continues, as landscape architecture and architecture both face particular issues accommodating women. In these fields women have chosen to join a profession (as opposed to home life or other type of work) that forces you to advocate your point of view. Our culture views it as unfeminine for women to be assertive, emphasize their point of view, show their will and dare I say, ego, and fight for their ideas. When you go present in front of what are still mostly male-dominated decision-making bodies, women are perceived to be speaking a second language when they are assertive. It is not only men that view it this way, many times women themselves are uncomfortable having to take strong positions.

QR: What you just said strikes me as the type of insight that is simple enough to be overlooked by the majority of people. How did you come about to this particular insight of professional life as a woman?

MS: It was long process of trial and error, and many times I was uncomfortable when I was put in a position to fight for my ideas. At those times I noticed that men had no problem asserting themselves no matter the situation. At first, I even found myself thinking 'how would a man handle this'?

QR: But you have also said that it is important for the new generation of women to assert their femininity and not try to be just like one of the boys.

MS: Yes, but when I was coming up through the ranks it was a different time, we didn't have role models. Also, you have to be strategic in this world. For example--very early in my career I had a decision to make in regards to site visits. To not expose myself to whistles, cat-calls, taunts, and a general lack of respect by the men on site I asked a male partner in the firm to do the site visits for me, this is a long time ago now. I thought that it was more important to finish the projects than to take a stand on the site. It is important to use all the tools available to you to get the job done and show, you may not win every battle but it is important that as a woman you do not forget that you have a larger goal in mind.

QR: After your resignation you were quoted in the Harvard Crimson as saying that it is crazy for someone to resign a faculty position in Harvard. In that quote you seem to allude that your successful landscape architecture practice is what allowed you the flexibility of having options.

MS: I view myself first as a practitioner. I get lots of satisfaction out of teaching, but my day job is to build things and the practice gives me the distinct opportunity of having options outside of academia.

QR: Can I then infer from the quote in the Crimson that experience has shown you that the professional world is more accommodating to women than the academic world?

MS: (laughs) You can draw your own conclusions, but yes absolutely, I have found that to be true.

QR: What do you say that we switch gears now and talk a little about some of your work. I was particularly interested in the visual analysis you did of the big box landscape. Is your firm beginning to pursue work in the strip malls?

MS: I have to say that right now our firm is getting larger and more urban civic and commercial projects than those in strip malls. We are now getting the signature spaces within cities that afford a lot of flexibility. The problem getting the strip-mall like projects is that developers are not willing to pay for real landscapes and are content with the minimum token landscapes that codes require. In the case of highways and other civic projects in the suburban landscape, there is a lack of political understanding and will to spend the money to humanize those spaces. The main problem is that there is an abundance of design need in the bland landscape but the client just does not exist. So for now I feel all we can do is bring up the issues and maybe through academia begin to engage leaders in government and business to take the improvement of the landscape as a real challenge.

Mesa Cultural Center landscape. Mesa, Arizona. Martha Schwartz, Inc. 2004. Images by Shauna Gillies-Smith.

QR: Your other analysis of the lack of power that architecture has in the strip seems to me similar to what Venturi has been saying, but then he returns to the architectural object to address some of those problems. You are telling us that it is the landscape that will really make a difference in these areas.

MS: That is right, in the suburban landscape architects are stuck on the object, which, although nice, lacks real power. Architects seem to have retreated to signature buildings in the middle of cities that are irrelevant to the majority of people. It is the responsibility of architects and landscape architects to care about the spaces that people actually inhabit. Without our collective advocacy cities and developers will do nothing.

QR: What do you think is the role of sustainability in this conversation?

MS: Sustainability is about realizing that you have only so many resources and we have a responsibility to the environment. For me a very pragmatic definition of sustainability is serving as many people with as few resources as possible which leads directly to density and urbanization. Sadly, density and urbanization as the final goal of sustainability are off the pages here in the United States, and urbanization is not only needed for sustainability in energy and resources, but also for cultural sustainability. Cities allow us to exchange ideas, to come together as a community and collect the necessary resources to build the urban institutions necessary for culture such as libraries, museums, schools, et cetera... East Darling Harbour, Sidney Australia. Martha Schwartz, Inc. 2005

East Darling Harbour, Sidney Australia. Martha Schwartz, Inc. 2005

QR: During your lecture at the GSD you made a point of bringing aesthetics into the conversation of sustainability, would you care to elaborate?

MS: Sustainability is now taking its first baby steps and many people think that the solution is solely technical. Think about it though - what gives a city its character is what happens between buildings, the open, public spaces. These spaces are what bring people together. In the UK, they understand this and have a mandate, like "thou shalt build sustainable public spaces." How do you do that? Design is the key to making sustainable spaces that people care for because they enjoy seeing and being in them. We need to design places that feel good, that we want to be in, and that are supportive of the human spirit. If not, what have you done? Certainly not sustainability. Gifu Kitagata Apartments landscape, Kitagata, Japan. Martha Schwartz, Inc. 2000. Images by Martha Schwartz.

Gifu Kitagata Apartments landscape, Kitagata, Japan. Martha Schwartz, Inc. 2000. Images by Martha Schwartz.

Creative Commons License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License .

/Creative Commons License

Pratt Institute DeanDSGN AGNC founder Quilian (pronounced: Killian) is the Dean of Pratt Institute’s School of Architecture, working across the school’s architecture, landscape, urban design, planning, and management programs. Quilian also serves as the Vice President for Architecture ...

3 Comments

well done, nice interview +q

I am guessing, since I am not a landscape architect, that it would be a frustrating exercise to design around an "object" building... maybe like trying to stitch a bowling ball to a concrete floor. and probably the reason why the Sydney Opera House works so well as an object building is that it is jutting out into the middle of Port Jackson--there is no landscape to design whatsoever. In how many scenarios today can we justify the iconic building?

but I agree, architects should be turning more attention to the space between.

nice analogy, although not water tight, i like it.

great stuff +q.

excellent interview. i specially enjoyed it when the idea of cultural sustainability came up, a pandora's box all by itself.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.