In 2011 the Massachusetts Institute of Technology celebrates the 150th anniversary of its founding, an occasion marked with 150 consecutive days of activities commemorating its long history of technology innovation. The most prominent of the exhibits, performances and symposia making up the celebration is the Festival of Art, Science and Technology (FAST), a series of events meant to highlight the institute’s often overlooked tradition in the arts. Organized as a six-part series of events spanning three months, FAST offers the public direct access to a body of work that transcends art as a means of representation to instead becomes an agent of social and technological exploration. On May 7th and 8th FAST culminates in the FAST Light festival, an open house showcasing a number of installation projects by both faculty and staff.

It is difficult to think of a design tool more capable than installation art. The medium straddles the blurred boundary that separates architecture and art, freely borrowing from each as it continually redefines itself. This fluidity coupled with the immediacy of its returns permits in-depth explorations into specific architectural topics such as tectonics, place-making and technology. Where else are the young and the inquisitive (which are by no means mutually inclusive) provided such opportunities without preconditions or preconceptions? Such freedoms are rarely granted within the traditional mode of architectural practice yet are necessary for the development of critically engaged professionals. Earlier this week I sat down with Professor Tod Machover, the director of FAST, to hear his thoughts on the purpose of the FAST Light installations and the process through which they were developed.

Aaron Willette - Whats been interesting for me as a designer is seeing how the arts are being pushed to the forefront of MIT’s 150-year celebration - when people think about MIT their first response typically isn’t to think about the arts. I’m really curious to hear why MIT is doing that, as I don’t doubt for a second that it was a conscious decision.

Tod Machover - Its a pretty simple story: about 3 years ago MIT started thinking about the 150th and it put together a committee of people from around the institute to think about how, given any possibility, MIT should represent itself. I guess by coincidence I got invited to be on the committee and was the only person from the arts at MIT there. I remember at the very first meeting we had people just brainstorming about what MIT is and how you could show what is prominent, and it just struck me that in the kind of arts that have grown at MIT, the reason they’ve grown the way they have, the way the arts fit into the general culture and the fact that disciplinary boundaries are so much more fluid at MIT than any where else, all of these things suggested to me that there was a story to tell that people didn’t know. The arts at MIT have grown so enormously in the last generation and not in a centralized way - I suggested that this was one of MIT’s best kept secrets and we should figure out a way to celebrate that both within and outside of the school.

Surprisingly everybody said, ‘Oh yeah, thats right... so what can we do?’ and there was a lot of talk of if the 150th was going to be a day celebration, if it was going to be 10 years, etc. So it was thought of as a semester and running from there I put together a group of people and we decided that the best thing to do was a festival with a slightly different twist: a festival that would serve both to pull together the existing community and tell the outside world that there’s a very different kind of arts community here that could have only grown up at MIT and on the other end really influence the creative innovative culture at the school. So to tell that story and to do it in a very MIT way we decided that instead of doing a week long festival or a two week long festival we’d do something that was spread out over the whole time and built around thematic clusters of long weekends starting in February and ending in mid May.

We’re taking a kind of deficit as a positive thing: MIT doesn’t have an overwhelming performance arts center and its doesn’t have an iconic art gallery, but it does have all these new building on campus. We decided to do something that was spread out not only in time but in space; to use some of the iconic spaces such as Kresge Auditorium, various parts of the new Media Lab building and the List galleries, but to also use both indoor and outdoor spaces at MIT that weren’t normally though of as gallery space. So that lead us to first schedule performances, discussions and exhibitions all over campus. It also go us thinking about literally doing interventions - commission and call for projects that use the campus and simply animate the campus in various ways. So thats what turned into FAST Light as a culminating and unifying idea for the festival.

The next thing we did was simultaneously look at the campus and think about it in terms of what was already there and what we might want to bring out. Basically we thought of two interconnected axes: one along The Infinite Corridor extended to Kresge Auditorium and to the Media Lab, and Memorial Drive and the (Charles River) waterfront as another. This is particularly exciting because, while its not that much of a revelation, it (the Charles River waterfront) is probably the most beautiful part of MIT and its always thought as a kind of back door to MIT rather than a front. We thought of activating those two axes and started looking for a variety of spaces in those areas that were interesting and might be offered to people as sites and started contacting people. I ran a course this past fall to basically teach people the background of art, science and technology at MIT; introduce them to a variety of people who were already presenting things in the festival; and help them little by little develop projects that might be considered for FAST Light. Then we put out a call for proposals in December for any student at MIT who wanted to, individually or as a team, propose something. By the end of December we had a group of faculty projects and selected student proposals and just dug in and started to build these things. We also made a schedule to install things starting in early February one-by-one so that by Saturday (May 7th) they’d all be in place.

AW - What has been your response to the individual projects? Do you feel they’ve conveying everything they’re meant to convey or are they successful in ways that maybe they weren’t initially meant to be - producing serendipitous moments that can occur with these types of projects?

TM - I think one of the great things is that the student projects take on a huge amount of work. A lot of students, mostly in the architecture studios, are given their problems and they work on them and realize them. I think its opening a door to give people a context and get them going with possibilities but to encourage them to completely invent their own projects from scratch. Helping them think them through and having 35 or 40 people all helping each other was about the most fun I’ve ever had. It was fantastic especially because I’m not an architect. I’m very good at running projects, helping people dream big and realize things. In this case it was wonderful because I could really help people find the right idea, pull in people as need to solve specific problems and give expertise in a various ways. I think we helped shape every single project in the just the right way. Once the project got to a theme and to a basic realization we didn’t try to pull it somewhere else. We tried to make it as deep as possible to where it was trying to go and kept pushing and pushing until it was as refined and powerful as it could be. At this point I think they’re all ready to be shown in the way that they’re being shown.

One of the nicest things about MIT is the general lack of hierarchy. Some of the faculty projects were designed in the context of the faculty’s studio or workshop, so they were collaborations with the faculty and the students. Then there’s fact that we have this whole FAST Light thing going up with work being done by undergrads, grads, junior professors, and very experienced people all being presented without qualifications. I think it would be very difficult to determine which is which because we found the appropriate form for each person. They’re all really very good in my view.

AW - For the projects I’ve seen already, not only are they being designed at MIT, they’re also being fabricated at MIT. I think that really says something about the direction of the school and the capabilities of the individuals involved. Would you say this add something to the projects, making them more ingrained in the nature of MIT?

TM - Yes, I think its absolutely true and I think its interesting for a couple reasons. Certainly for the students, its really interesting in terms of experience. Its fantastic to think of a big idea, but its wonderful to then follow it through all the way as in many, many case your idea doesn’t really become concrete until you work out every detail. The great thing is you don’t know what you’re going to find out. You could find out that you thought about the scale the wrong way, the material the wrong way, the way something joins up.

I like a lot of these projects because many of them involve post-electronic interactives. There are very few of the hokey, first generation lets-take-an-artifact-of-video-feedback-and-play-with-it or glorified Wii controller projects. The interaction is pretty subtle and sophisticated, like The Mood Meter for instance. There's some pretty crazy code running that can determine a facial expression from anybody’s face as they walk by, and it doesn’t make a big point of that. You don’t see posters explaining how it works.

AW - Right, its not about glorifying the technology, its about what the technology is doing and the experience it creates.

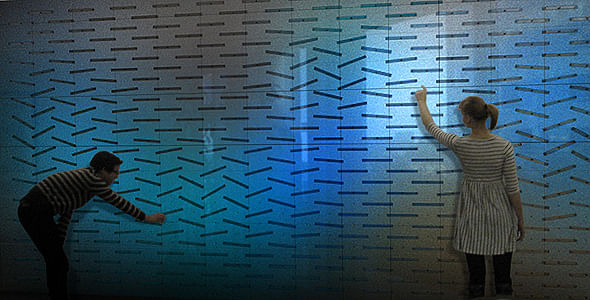

TM - It is. Like with Maxwell’s Dream. I love the form: its just magnets and this pleixglass wall. Just the fact that you’ve got large elements that are fun to grab with your hand. They’re orderly but not symmetrical - they’re magnets and by physically moving them you perturb and entire wall full of these things. The amount of force that you put in sends a magnetic charge in different ways, it also has sensors and lights underneath so that it glows according to the propagation patterns. Again, its very physical and its got a sound to it when you move these things. And these sounds aren’t coming from loudspeakers, its the physically the scraping of the plexiglass and the little elements moving around. I think its powerful that there’s something really elemental and physical and sophisticated about these things. I think we pushed them in that direction and I think that maybe its the kind of context we gave to everybody.

I hadn’t thought of this until just this second, but most of them are collective activities also. They’re not the kind of interactives like you’d see in a science museum where you go up to a station and you’re interacting with it to understand a concept. In an art museum it might be that you’re interacting to be part of an experience, but it usually not all that sophisticated. Almost all these are designed so that its a public space. Like Bibliodoptera where you have these little (vellum) butterflies hanging from the ceiling. They all have LEDs on them and they’re measuring audience or public movement in the space and the lights are flickering depending on who is walking where. Its more interesting if there are a bunch of people, its not the kind of thing that you look for a time when no body is there to go and ‘play’ the butterflies. It doesn’t feel like that, its an enhancement of what people would normally do. I think what I want to say is that they’ve all been imagined as ways of augmenting public life here on campus, public sensitivity to what the campus, what people do and whats going on around you. Especially in a campus which people are often in a rush and don’t stop to pay attention and to do things with other people. Its just a contribution and I think its interesting.

AW - What are the benefits of these hands-on projects? You mentioned earlier that with the architecture students they’re not used to creating their own problem and simultaneously solving it…

TM - Thats the biggest one. For the arts in a place like MIT the biggest thing to learn is simply how to ask an appropriate and deep and impactful question out of no where. Its nice to have a context like animating the campus, having a concert, or something simple. But its a profound thing to be able to both look at yourself and what you’re capable of, look at the world and see what you think is needed and look at this moment and simply come up with a project and push it, refine it, define it, get it as far as it can go until its just right for that idea. You couldn’t learn anything better than that. To have people help you learn how to think about it so that the next time around you can do that much more yourself, thats really valuable. What I try to teach my students is whatever it takes to learn how to put yourself in the position of someone experiencing whatever it is you’re making and to do that as early and as often in the process as you can. The more you can do that in your imagination and do it accurately the better inventor and designer you’re going to be. We have all kinds of tools and tricks to help us, but nothing replaces actually having built it, installed it and seeing it in the real world. And second best to that is to imagining that situation right here (points to head).

I think its really important to learn how to talk about these things with colleagues. The great thing about the way these projects developed is that we had team that formed over the fall, and then the teams learned to talk together. Generally the teams formed naturally. They’d start with a person or a couple of people and then those people would go out and seek the other expertise they needed. They had to learn how to find complimentary members and really work together, and they worked very well to then help each other out. It was great to have so many good ideas that we could help develop. The nice thing about the projects that were developed was that they all really have the right balance between the design, the realization, the technology and the idea. There was nobody who didn’t finish on time.

AW - What was that curation process like for you to bring all these different projects together and organize them into a whole that can be presented in a logical manner? It must have been incredibly challenging to find the common thread that ties everything together and somehow celebrate that.

TM - The first thing I did was put together a group of leader and and administrators from the school. Five or six people who are responsible for overseeing things at MIT to really dig in and decide what elements we wanted to bring together and what people we wanted to make sure were involved. We did that already starting about 2.5 years ago. I did the same thing with faculty starting about 2.5, almost 3 years ago when we knew we were going to do something. I started having large meetings that I’d invited 15 − 20 people to from different departments to come together around the idea of doing a festival, what they thought a festival should be, what they might want to present. And it turned out that most of these people, myself included, had never met each other.

So the first experience was getting the leaders together to think of big ideas, get faculty to simply meet each other and I put together a faculty curating committee. They were really a pretty diverse group; my goal there was not to have many people, but people who were committed, really first rate at what they did and interested in working together. I can tell you it was Meejin Yoon, from architecture; Evan Ziporyn, who is a composer in Music and Theater Arts; Jay Scheib, a media theater director in Theater Arts and Dance; and Erik and Martin Demaine, a father-son team. Martin is an artist-in-residence at the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory and Erik is the world’s expert in computation origami, MIT’s youngest tenured professor and MacArthur Fellowship winner. Also Pawan Sinha, an Associate Professor in the Brain and Cognitive Sciences department.

And so with any big project like this we kind of went at it from all the different angles. There was the high level angle of what story we want to tell, what image about MIT and the community we want to project and what we can do that will galvanize and interest the community. Then there was what different forms and elements did we want to present, how may of which kinds of events, how much we can do timing-wise and budget-wise and how to combine both audiences and experiences so you know its a festival. We didn’t want to do academic conferences with just an analysis of work but we did want to mix things up. For instance, the opening week in early February was on the tradition and past of arts, science and technology at MIT; we had a museum opening with Stan Vanderbeek’s work and a whole colloquium that went along with that; discussions on the interference of visual arts thinking with cybernetics and system theory in the 50’s and 60’s at MIT; and then a big day on the history of music and technology at MIT. All of them combined either a gallery show, concerts, hands-on demos, discussions and debates. From the very beginning we have been pulling in a very diverse public in terms of age and experience. Many, many people who are coming to these things haven’t, as far as I can tell, been to events at MIT before.

AW - What are your hopes for the upcoming FAST Light event?

TM - I think the event is going to be great. It is always hard to know how many people will show up and who they will be, but I have a good feeling about this. We’ve got a fantastic team putting this festival together. Its a small team and we’ve done a remarkable amount with the resources we have. The good news is that FAST is part of the MIT 150 celebration, although we’ve been mostly responsible on our for getting the word out about Festival events. We do have a pretty good social media campaign and there have been articles in the local papers. We’re in the catalog for the Cambridge Science Festival so everybody who gets their brochure will see FAST Light.

I think the words gotten out a certain amount. Every single thing we’ve done so far for this festival has exceeded my expectations in terms of how many people were there and how much energy was there. People have the attitude I was hoping for, which is this-sounds-really-interesting-and-I-just-want-to-be-here. Its felt like the whole context for everything we did, whether it be a concert, a debate or a show, brought in a very interesting collection of people. I’m kind of expecting the same thing to happen for FAST Light, especially on Saturday. Even though some (of the installations) are hidden, its very coherent in that they were all thought of together: they way they’re spaced, the way they point to each other, the way they resonate with one another. Its all carefully thought out so it doesn’t feel random. There are enough things that I think just looking at your map and just finding everything will be great fun.

All photos courtesy of MIT.

Aaron likes his music loud, his coffee black and his whiskey neat. A designer and technologist in Brooklyn, NY, his current investigations relate to the practical application of computational tools and their intersection with traditional interpretations of craft and technique. Aaron is a founding ...

3 Comments

I was actually present while these guys were presenting their designs in November... including Dis(course)4, by Craig Boney, James Coleman and Andrew Manto. Great job to all the students..this one was indeed beautiful..and they received constructive and great crits from their jury.. Congrats again MIT!

Where are they go?

Wao So amazing .

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.