So, we have come to this ship in a frozen fjord to think about the ways we might communicate our concerns about climate change to a wider public; we will think about the heady demands of our respective art forms, and we will consider the necessity of good science, and shall immerse ourselves in the stupendous responsibilities that flow from our stewardship of the planet, and the idealism and selflessness demanded of us as we subordinate our present needs to the welfare of unborn generations who will inherit the earth and thrive in it and love it - we hope - as we do. But first, we must remove our wet boots.

-- Ian McEwan, A Boot Room in the Frozen North

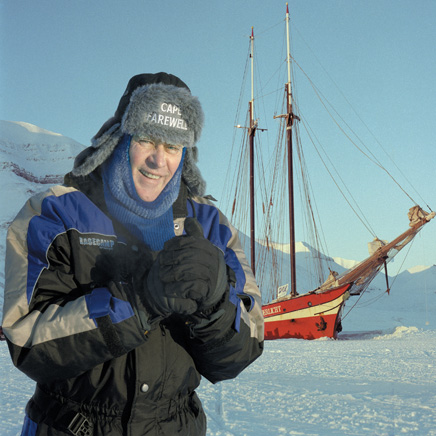

Through a series of expeditions on a 100-year old Dutch schooner that traverse the vast, beautiful and uncharted territory of the High Arctic, Cape Farewell has brought together artists, scientists and educators to collectively address and raise awareness about climate change. I met with Cape Farewell's creator, the artist David Buckland, to talk about the Life Aquatic, and the role artists play in documenting this tremendous and remote landscape, translating the profound experience of witnessing glaciers melt into the sea, and making visible the connection as to how our urban behaviors register as geologic shifts and changing weather patterns throughout the world.

At the foot of Kongsvegen glacier, Tempelfjorden, Svalbard, 2004.

Artists and scientists in front of the Noorderlicht, 2005.

Alex Hartley on the bowsprit of the Noorderlicht, sailing through ice, 2004.

What were your first impressions of the arctic?

We sailed very far north -- north of Norway -- about 600 miles from the North Pole. It was 24-hours of daylight. They say the arctic is like a drug -- you're completely hooked, and you go back again and again. Which I do.

David Buckland and the Noorderlicht, 2003.

Being the instigator of these expeditions, how did you hook on to this subject? Were you working with scientists, or doing projects that addressed climate change before this?

Well, I'm an artist and I'm also a sailor. I found out these scientists had made a mathematical model of the North Atlantic. If you know how complex the seas are, which I did -- it just seemed ludicrous and fascinating that you could translate that information into a mathematical structure. That was a project of The Hadley Centre , which is dedicated to studying climate change. It's very difficult – especially for artists -- to go into the future. There's no structure -- you can only fantasize. But what these mathematicians have done is make an intellectually robust way of projecting yourself 20 years ahead, with some degree of certainty.

The Hadley Project connected me with oceanographers, and soon you find that the worldwide science community is all attached to itself. Ten years ago they knew what we know now -- that climate change is a real issue.

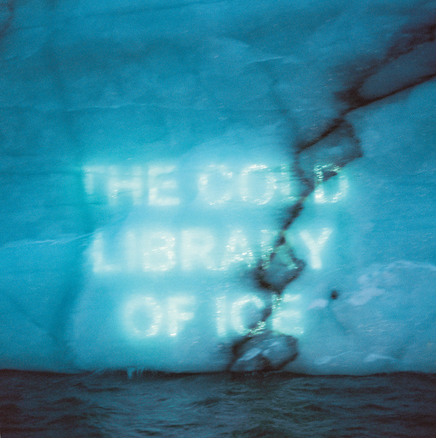

David Buckland, Ice Texts, 2004-2005.

Are you producing art with the intention to educate?

No, I produce art to make art. That's been the criteria of every artist involved with the project. They each know what constitutes a piece of art, in their own terms. The deal was: if you're inspired to make a piece of art, great, if you're not, that's fine. And the fact is – they’ve all come back making art, and they all stand by the art they made. It’s not trying to be propaganda – it’s a different kind of storytelling than being an agitprop.

Heather Ackroyd & Dan Harvey Stranded, 2005�2006, (process).

Heather Ackroyd & Dan Harvey, Stranded, 2005-2006, (detail).

How has the education program developed? Was it influenced by the social structure of the ship, working on site with artists and scientists?

Well, there were two kinds of drivers for this. First, the scientists were fantastic but they couldn't get anybody to listen to them. There was no media focus, no media story -- they were just singing in the wilderness, so that was a problem. I thought: that's one thing we have to address, because their message is serious. Second, it became obvious that every kid leaving school should understand climate change. Our education program put climate change on the GTSE’s: a rigorous exam for 16 year olds in the school system here. So, we have an education team that delivers, and that’s separate from the art team, though they work very closely together.

The problem with climate change is that it covers everything, so if you just look at it from the point of view of science, then you're missing most of the problem. Essentially, it's a cultural problem, a sociological problem and an economic problem. Our education team doesn’t like all the compartmentalization of schools, so we have drama working very closely with science, two departments that don't usually talk together but can find common ground as this actually affects them both. And they can begin to tell the stories with a common language. One of the leaders of this is Suba Subramaniam, who is Indian and used to be a science teacher but also a Bharat Natyam dancer and has a Bharat Natyam dance studio. She doesn’t see the conflict in this. And Colin Izod used to be an English teacher and now runs a media company , so it’s the same thing.

Gautier Deblonde, From The Svalbard Series, 2003-2005.

It's interesting that education curriculum repeats the cross-fertilization of disciplines that were on the ship.

It underpins everything we know about climate change. Everyone thinks climate change will restrict us, that it's a problem, but actually -- it's an extraordinary opportunity that's being forced upon us. And I think we probably need something, because were going down some really bad roads. You can't deal with it without changing the nature of society -- and society needs to become much more aware of other societies. Everybody has to work together and you can't stand separate. If that doesn't happen, then you won't solve climate change, and if you don't solve climate change, well -- then we're in for a lot of trouble.

Heather Ackroyd & Dan Harvey, Ice Lens, 2005, (process).

Heather Ackroyd & Dan Harvey, Ice Lens, 2005.

How did the artists initially approach the site? Did they come with a set of tools, or processes?

Artists do wonderful and weird things nowadays. What I try to do is find representatives of the major forms of art: painting, sculpture, music, writing, photography, film – and the whole breed of artists that are conceptual. The artists brought very few tools to do experiments. Antony Gormley brought two swords, because he felt the only material useful to work with was either snow or ice. I brought video and projection equipment, because that's what I do. But, for example, Alex Hartley discovered an island. That's his art. The actual piece was first the island he discovered, but also all the legal jargon that he needed to make his claim. But that's not the point of what he did -- his point was to say, isn't this ludicrous? I can go up to the arctic and there's this little piece of dirt that doesn’t mean anything to anyone, and I can claim it as mine. If you have that relationship with the planet, its so unsharing, so defining, you can’t carry on like that. So that’s what his artwork unraveled.

Nymark (Undiscovered Island), 2006, (detail).

Alex Hartley, Nymark (Undiscovered Island), 2006.

Some of the projects seemed like they would require teams to produce or build -- how did you collaborate on the boat and utilize people to work on different projects?

It's totally unforced and everyone has their own way of dealing with it. The boat is a schooner and is nearly 100 years old, and it takes about 4 or 5 of us to put up one sail. We have a captain and a first mate and a cook, but that's it. So we sailed the boat. Some people wanted to and some people didn't. Everybody joined the watch-system, though some people got very sick and had to drop out. Whoever could help did -- it was sort of a democratic anarchy. And -- of course -- if someone wanted to make something --

The oceanographers were really pressed - they had to stop every hour and drop a meter below the boat. It's a lot of physical work, so we all helped them and were aware of what they were doing. But we also swapped stories, and walking ... endless hours of walking. It was a way of absorbing, of having conversation, of experiencing this unbelievable place - a way of observing it.

Rachel Whiteread, In sub-zero kit, 2005.

Rachel Whiteread, Embankment, Tate Modern Turbine Hall:

The Unilever Series, 2005. Photo: Marcus Leith.

How did the scientists respond to the research methods of the artists?

Oddly enough, the community that’s been most open to this has been the scientific community. They understood that their message wasn't getting through and they also understood the power of creative communication and how important it was for their argument. In the beginning, everyone would have to conference about each thing, but now they totally get what we're doing. Scientists have to work together, they publish, they have peer review, its how their system works. Artists don't ... they kind of know each other. They’re guarded, mistrustful and don't want to be manipulated. They're ferociously independent in many ways. There are also collaborations among artists, but in a completely different structure. So for them to absorb this as an idea is different. As for artists understanding the scientists? Yeah, there's a hunger.

Dr Simon Boxall, Launching a disposable temperature probe during the transect, 2004.

Your next expedition is a switch from artists and scientists to students.

No, no -- we're doing both. We're completely insane and are doing two expeditions back-to-back. Cape Farewell chartered the boat for nearly a month so we're actually taking a group of 14 youngsters who are about 15 or 16, and they are going to sail the boat, with about six adults. The kids are going to rule their endeavors. There's three from Canada, one from the United States, and the rest from the UK and Europe. They're all motivated and are going to come back as climate ambassadors, and for them it’s the chance of a lifetime to be a part of this truly exciting project.

Are the students given tools to communicate?

We chose the schools for their demographics. An Inuit school up in the high arctic, a kid coming from a big comprehensive in Germany, inner-city schools, country schools. The school first gets on board with the project - they run a competition, and the kids come up with a science project, an art project or a communication project. We're feeding it live on the internet the whole time -- we're very getting canny at using the internet, and we're getting better. We want to make a sort of MySpace area where kids can communicate with the students that are up there. But it's funny that you ask me, are we going to teach them how to communicate? Oh, we'll tell you how to blog ...

Ha! I guess they’d be the ones teaching us! So, you'll do a crew exchange?

Yes, then with the artists and scientists, we're going to sail from Spitsbergen to eastern Greenland along the 80th parallel north to, a passage only now possible due to the melting sea ice. So we're going to virgin territory. It’s a very ambitious sail, nearly 2000km. Far north, the gulf stream sinks, driving all of the ocean currents. Scientists are trying to understand this furiously complicated physical stuff. We're going to a lot of oceanography from Spitsbergen to Greenland and then across the Denmark Straight to Iceland. So we're crossing important pieces of sea where we're doing some real science. And there are also American, Canadian and British, Indian artists on the boat. It's designed to be a new group. It's a new art -- much more conceptual. There are some big names, but most of the artists are in the 20s and 30s, and they are making a very different kind of art, that doesn't fit into galleries.

So who’s on board?

Laurie Anderson, and the writer Vikram Seth . There’s Amy Balkin , a California artist, shes come up with this concept: why don’t we just make the atmosphere a world heritage site? Then you can’t use it as a dumping ground. How obvious! Fantastic art, she's quite political. Beth Darbyshire makes art that lands in society. She re-designed the $2 Canadian bill, rewrote the English anthem. Brian Jungen, a Canadian artist, completely alters everything, takes something that’s consumable, and re-twists it so you think about it in a different way. He made a whole whale structure out of recycled plastic chairs. Strange and interesting work. Who else? Oh, Will Hunt -- a performance artist who gets so emotionally involved with what he does, and you’re never quite sure what it means. There’s no other way of telling the story than through the performance. If you throw those kinds of thinking at this idea then you're going to come up with something fascinating.

Gary Hume, Hermaphrodite Polar Bear, 2003.

Have you considered taking an expedition of the people who are shaping our cities: architects, landscape architects, planners, developers?

Peter Clegg of Feilden Clegg Bradley came up on one of the expeditions. It was fantastic to have an architect on board. Peter actually worked with Antony Gormley , the sculptor, the whole time. A city planner ... it's true we haven’t really approached it. I'm not sure if that group isn't better just working in an urban situation? I'm not sure how much I can keep justifying going up to the arctic. When we first started, climate change wasn't being discussed, so we asked the questions – how do you inspire people, how do you inspire the media to look at this issue, and how do you inspire artists to work in response to it? And I thought, well – if we take a ship up to the arctic, the media will be interested. You can see the arctic physically change, and the artists try to register this in their work. As Ian McEwan points out, the poles are sort of a feather in the wind, a canary in the coalmine. If the poles are damaged, that is the barometer of the planet. But a lot of the artists work has been made since they came back, and it’s very urban. I'm interested in an art that will motivate people to work on these issues in the middle of an urban situation.

Antony Gormley and Peter Clegg, Three Made Places, 2005.

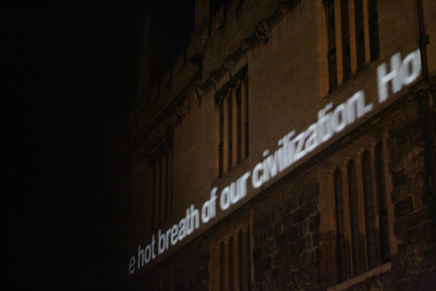

Peter Clegg's Ice Towers, and Ian McEwan's projected text shown at The Ice Garden, 2005.

How then do you register and make visible the connection between our cities and the changes in the arctic?

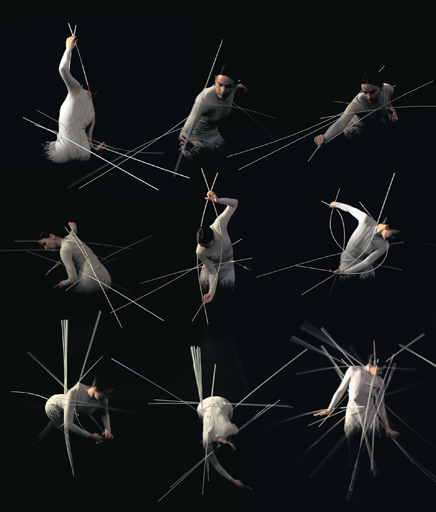

The choreographer had us do these wonderful things, these dance-like walks. But there’s this warm body and you protect it with all your clothing, but if you sat down for half an hour, you’re not going to last very long. You protect yourself, you have this amazing care about yourself, and you think, “Well - wait a minute. If we have all this care about ourselves, and the group we're with, why aren’t we caring about the planet in the same way?†It’s a symbiotic relationship. The earth is the most complicated organism in the solar system that we know about, and human beings are equally complicated organic systems. The two have got to work together; you can't compete against one another. We've got to change our behaviors, its just logical. ... How did we get on that?

Siobhan Davies, Walking Dance, 2005 (still).

Siobhan Davies, Endangered Species, 2006 (still).

The question is: how do you take the story up there and make it relevant to what's happening down here? In the arctic, there's no background noise, all noise is filtered out, so you think differently, you think clearer. It’s a refined situation with a group of people who are all basically thinking about the same thing. It’s the oddest workshop in the world. It inspires you, and you come back and continue.

Max Eastley, Recording sea ice from the Noorderlicht, 2004.

Max Eastley, Glacial Sound-scape, 2005 (detail).

It's about telling human stories. The scientists will tell you that the earth has risen by 4 degrees. So? For most people the temperature changes 30 degrees in a day. What’s this 4 degree rise and what does it have to do with me? I think what the artists have done is tell the human stories, bring the human scale. Artists can bring the emotional layer, which scientists don’t use much - it’s not a common tool for them. Well, it’s not a quantifiable tool. Actually, I think the way many scientists understand the world is quite emotional sometimes. But it’s expressed through mathematical terminology. "It has elegance," they say. Pretty emotional stuff.

Does all this work give you optimism for the future?

I've been working on this for eight years and suddenly in the last year or so it’s become a subject that everyone wants to talk about. I've known most of the people in this business. I recently heard Nick Stern give a talk on the Stern Report , the great economic proposal. There was this feeling among the scientists that now there is this possibility of really major change. I think it's the most influential economic document of the last 50 years. He’s actually given the world a blueprint as to how to operate. If we can deliver these steps, it’s going to be a miracle. We have to transform our sources of energy; we have to transform our economies, value systems. Not greatly: we have to evolve them, not dump that lot and start again. It's all doable and it's amazing that this guy came up with this very logical piece of thinking.

The math is very complicated, full of alphas and omegas, but the objective of this economic formula was to evolve a statement on ethics. You can’t have an economical structure that’s unethical, because it will ultimately be destructive for all. I was thinking, great -- this is an artist talk! So I’m very excited for that.

I think I have evolutionary optimism, rather than hope, which is always blind. People have to work very hard at this and it’s a creative challenge. We have to rethink all these dead avenues of operating in the world.

So there you go: it’s good stuff. This climate change business is really good for us.

Ian McEwan,

Extract from The Hot Breath of Our Civilisation, 2005.

Upcoming:

- 2007 Expeditions (Southbank to Greenland)

- 2007 Exhibition Series .

Creative Commons License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License .

/Creative Commons License

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.