In the US architectural profession of the 2020s, and newfound scrutiny over workplace conditions from unpaid overtime to a poor work-life balance, architecture competitions have become the subject of debate over how the profession values itself and is valued by wider society while also ensuring public-funded projects are not exploited as avenues of cronyism. However, a reading of the past 100 years of the profession tells us that we have been here before.

“Open, unpaid competitions are an abomination. It is folly, and something worse, to ask the members of a respectable profession to show us their ideas for nothing, and to expect to get their best ideas or the ideas of the best among them. Limited, paid competitions, where certain chosen artists are asked to submit schemes for comparison, and are promised a fair reward for their trouble, should stand on a different footing. But they are often managed with so total a lack of respect on the client’s part, not only for art, but for mere labor, and so total a disregard for the precepts of business good-faith and common honesty, that they, too, have become a by-word and reproach.”

Setting aside its odd cadence, the above quotation could have been written in 2024, given how neatly it fits with contemporary debates on the use of architecture competitions for procuring work. “For centuries, the design competition has been a trusted means of procuring architectural services,” a research article in The Journal of Architecture noted last year. “Yet competitions themselves remain a source of considerable anguish and contention within the architectural community.” The past 12 months have also seen competitions described as “far from perfect” by The Architectural Review, and “cut-throat” and “bad for everyone” by Building Design.

In fact, our quotation comes from 1890, written by prominent architecture critic Maria Griswold Van Rensselaer for an article in the journal North American Review. Van Rensselaer continued the article by pleading with architects and clients to not engage in unpaid competitions, and for clients of a paid competition to “not try and get something for nothing, or more than he asked for the price he agreed to pay.”

At this juncture, it is worth isolating what Van Rensselaer meant by 'competitions.' There are several forms of architectural competition operating across the profession today. Ideas competitions, for example, offer students, professionals, or both, an avenue to submit unbuilt speculative schemes. Often calling for ideas beyond the imminently practical or deliverable, ideas competitions can serve as a way of stoking debate, discussion, or creativity on an interesting or relevant topic, or building a community. Van Rensselaer's focus, and the focus of this article, is instead on competitions as a method of a client procuring architectural services not by approaching and commissioning an individual architecture firm, but by calling on multiple firms (whether unrestricted or a limited list), to submit proposals for a client or jury to choose from.

I discovered Van Rensselaer’s article while reading George Barnett Johnston’s book Assembling The Architect: The History and Theory of Professional Practice, as part of my research for our ongoing editorial series Archinect In-Depth: Licensure. As has already been set out in the series, Van Rensselaer was writing at a formative moment for the US architecture profession. The American Institute of Architects had been established just 30 years previous, while the Uniform Contract, which sought to formalize the relationship between US architects and their clients, was only two years old. It would still be seven years before Illinois became the first state to require licensing for architects in 1897, 40 years before the creation of NCARB in 1920, and over 35 years before Frank Miles Day’s seminal The Handbook of Architectural Practice would be published in 1920. Controversy, criticism, and unease over architecture competitions are literally as old as the modern US architecture profession.

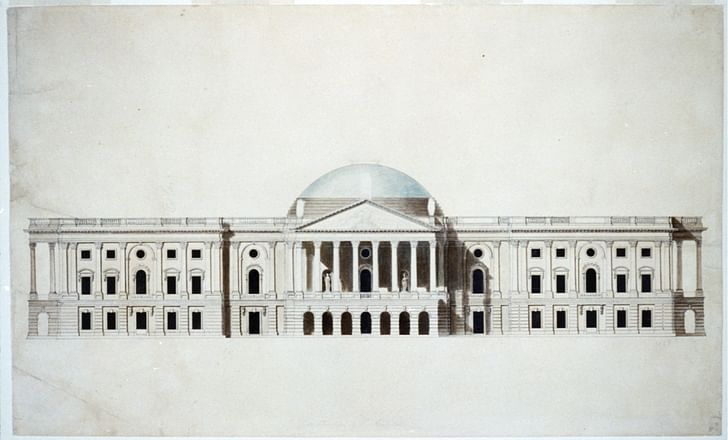

Architecture competitions themselves are much older. The Acropolis in Athens, Greece, was designed through an architecture competition in the fifth century BC, as were the Spanish Steps in Rome (1419) and the Brunelleschi’s Duomo in Florence (1418). Some of the world’s most recognizable governmental buildings were the result of architectural competitions, such as The White House in Washington D.C. (1792) and Houses of Parliament in London (1835), as were celebrated 20th-century works from Sydney Opera House (1955) to the Centre Pompidou (1971).

While architecture competitions, open or invited, will be a familiar concept to the US reader, they are considerably more common in Europe. In both the EU and UK, laws designed to prevent misuse of public funds require competitions to be held for public-funded architecture projects over a certain value. In this context, anonymous design competitions judged by an impartial jury can have the advantage of easing concern among the public that architectural services for public buildings could become instruments of cronyism or corruption.

Controversy, criticism, and unease over architecture competitions are literally as old as the modern US architecture profession.

Architecture competitions in the US date from the nation’s founding through the Federal period (1790-1830), with notable examples including The White House, won by James Hoban in 1792, and the US Capitol, won by William Thornton in 1793. As Johnston notes in Assembling the Architect, the genesis of the modern profession in the late 1800s coincided with a romanticization and popularization of architecture competitions by American architects returning from studies at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

“The system of concours d’architecture was institutionalized in fledgling American schools of architecture and in drafting clubs and ateliers in cities across the nation,” Johnston writes. “Perhaps even more significantly, architectural competitions became the chief mechanism under the Tarsney Act of 1893 for selecting architects for the design of federal buildings, the culmination of a long-sought effort by the profession for private practitioners to gain access to publicly funded work.”

This romanticization of architectural competitions was not universal, however. Johnston also describes a profession at the time in which “many commentators held the opinion that architectural competitions were a means by which owners could extract something for nothing in the form of architects’ uncompensated ideas and labor.” Johnston cites “an especially pernicious practice” where owners would solicit unpaid sketches from several architects and only offer the paid commission to one.

“Members of the AIA especially decried the demeaning manner in which colleagues were often willing to offer uncompensated services on the slightest chance of getting a job,” Johnston writes. To commentators such as Van Rensselaer, unpaid competitions were particularly damaging to a fledgling profession still working to solidify and articulate a sense of respect, legitimacy, and value.

If such concerns over unfair compensation within architectural competitions sound familiar to the modern reader, so too will the other objections of Van Rensselaer’s time. As Johnston notes, a lack of transparency in the jury process, the legitimacy of the owner’s intention to deliver the winning scheme, the lack of clarity in briefs and programs, and the “potentially deceptive nature of architectural renderings” were all grounds for opponents to attack the competition process.

Unpaid competitions were particularly damaging to a fledgling profession still working to solidify and articulate a sense of respect, legitimacy, and value.

The polarization surrounding architecture competitions at this time is best seen through the varying positions taken by the American Institute of Architects, who had proposed and advocated legislation as early as 1875 designed to offer private practices the opportunity to design federal buildings. At the time, primary responsibility for such a role fell on the Office of the Supervising Architect of the US Department of the Treasury. Proponents of competitions argued that such positions were appointed based on political patronage rather than professional experience, leading to what competition proponents argued was a misuse of public funds and artistically inferior work. Based on AIA advice, the US passed the Tarsney Act of 1893 to require that federal buildings undergo an architecture competition, establishing protocols for impartial juries, fee standards, anonymity, and a scoring process based on merit rather than political patronage.

Less than two decades later, however, the AIA began to articulate criticism of the competition system shared among member architects and critics such as Van Rensselaer. At the 1908 AIA convention, AIA President Cass Gilbert described the competition process of the time as a “wasteful system,” arguing, “I think it would not be too much to say that the architects of this country annually expend over $1,000,000 in competitions from which they receive no return. How long can the profession stand this drain?”

The AIA’s Committee on Competitions meanwhile argued that because the Tarsney Act only applied to federal buildings, unregulated private competitions had proliferated across the industry mired by abuses of fairness and business ethics. The committee and wider institute ultimately adopted a position “that an architect be employed upon the sole basis of professional fitness, without resort to competition.”

While the act disappeared, however, the debate over the merits and faults of design competitions has resonated through the profession across the 20th century to the present day.

Derided by opponents, including those who originally facilitated its passing, the Tarsney Act was rescinded in 1913 after only 30 years, eliminating the requirement for competitions to be held for the design of federal buildings. While the act disappeared, the debate over the merits and faults of design competitions has resonated through the profession across the 20th century to the present day. In a 1989 article titled ‘For Architecture, A Little Competition Can Go A Long Way’ the Washington Post explored “an increasingly significant debate among architects and their clients” about design competitions, itself inspired by an exhibition hosted at the time by the National Building Museum on how competitions sat within the US architectural landscape of the 1960s, 70s, and 80s.

In 2007, meanwhile, The New York Times demonstrated how little had changed in the discourse surrounding competitions. Noting that “architects can be deeply ambivalent” about entering competitions, the piece saw several notable architects listing competition pros and cons mirroring the discourse of 100 years ago: prestige, openness, and creativity on one side, corruption, exploitation, and unreliable delivery on the other.

In the US architectural profession of the 2020s, and newfound scrutiny over workplace conditions from unpaid overtime to a poor work-life balance, architecture competitions represent growing divergences among the community. Some hold an outlook that continues to romanticize the concours and the starving artist that triumphs by them. Others hold an outlook that project competitions are an avenue for younger firms to gain commissions and publicity without deep prior connections to clients, or that competitions are necessary to guard public funds against corruption or cronyism. Finally, there are those who argue that architects should be regarded not as artists but as workers, where the concept of producing free or financially unviable services in the name of competition is representative of an underpaid profession and a broken business model.

When assigning blame for such conditions, it is convenient to point to seminal moments in the relatively recent history of the profession. Perhaps it was the neoliberal agenda propagated by Reagan and Thatcher across the 1980s. Perhaps it was the Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890 or Tarsney’s competition legislation from 1893. Perhaps it was Adam Smith’s fathering of Capitalism in the 1700s.

When the Ancient Greeks held an architecture competition for the Acropolis, was an unspoken standard set for what civilizations across time have expected of their architectural landmarks, including a romanticized, sacrificial, ‘chosen one’ mentality for their conception and design?

When studying how the architectural profession has historically engaged with design competitions, and the stubbornly cyclical arguments raised for and against them across time, one wonders whether the origin of this debate go deeper than Reagan, Sherman, Tarsney, or Smith. When the Ancient Greeks held an architecture competition for the Acropolis, was an unspoken standard set for what civilizations across time have expected of their architectural landmarks, including a romanticized, sacrificial, ‘chosen one’ mentality for their conception and design? Has the battle between the architect as an artist and the architect as a worker become engrained in the practice of architecture ever since, merely exploited by the transient political and commercial actors of the times?

“The Tarsney Act is dead,” one commentator noted in 1915. “Dead but not forgotten. Hope springs eternal in the gambler’s breast and some day will rise up one greater than Tarsney who will enact a law whereby our Uncle Sam again will get, from the architectural profession, with its hearty consent, something from nothing.”

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.