Fellowship opportunities provide design professionals with a bridge to explore and expand their research in an academic environment. Educational institutions have increased their fellowship opportunities for students, graduates, and emerging design professionals. Within these past few years, there has been a distinct push for more social justice, race, and gender-focused fellowships and their relationship to the built environment. Fellow Fellows is a series that focuses on the role fellowships play in architecture academia by connecting with the fellows themselves. For this iteration of Archinect's Fellow Fellows series, we connected with Todd Brown as he embarks on his new role as the University of Texas Austin's 2021–2023 Race and Gender in the Built Environment Fellow.

Brown dives into his eclectic academic background that combines a series of disciplines that are often seen as separate approaches intertwining later in practice. After receiving his Master of Public Health and later a Master of Architecture, Brown realized that architecture "did not prioritize racial and many other social considerations in its design philosophy." This eventually propelled him to pursue a research doctorate that would enable him to blend his interests in architecture and public health. He explained: "I decided that my next goal [after receiving his Master of Architecture] would be to complete a research doctorate that would allow me to synthesize my knowledge of architectural design and public/environmental health issues while emphasizing social, environmental, and racial justice."

During this interview, Brown reinforces the idea that an architecture education not only provides one career path but a foundation to pursue many. After receiving his Ph.D. in Environmental Psychology from The Graduate Center, City University of New York, he uses his multidisciplinary background to further explore the built environment and challenge the current perspectives between these disciplines.

*Fellow Fellows aims to understand what these positions offer for both the fellows themselves and the discipline at large by presenting their work and experiences through an in-depth interview. Fellow Fellows is about bringing attention and inquiry to academia's otherwise maddening pace while also offering a broad view of the exceptional and breakthrough work done by people navigating the early parts of their careers.

Can you share with us your academic journey and how you became interested in bridging the fields of architecture, psychology, and public health?

My academic journey interestingly begins with me being homeschooled my entire life—1st to 12th grades—before college. My late mother, Deloris Brown, who was also my teacher, noticed that I gravitated to and excelled in mathematics and art. She, without having any real knowledge of what the field entailed, encouraged me to pursue architecture as a career, beginning when I was in elementary school. While in my senior year of the homeschool program, I decided that I would apply to schools of architecture and ultimately ended up staying in my hometown and enrolling at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC).

In my third year as an undergraduate student, I took a course in environmental design which got me highly interested in sustainable architecture. This interest coincided with my recruitment into UIC’s public health school, which appealed to me because of the available concentration in environmental and occupational health sciences. It was my intention to learn the science around the prevention, assessment, and management of environmental hazards in relation to architecture and human health. Little did I know that my decision to go to public health school would ultimately change my entire career trajectory. While obtaining my Master of Public Health (MPH), I was exposed to the topics of environmental justice and environmental racism—themes that had never been introduced to me during my undergraduate architectural education. These social and racial aspects of environmental health captivated me more than the technical considerations of ecological sustainability alone. It was after this exposure that I realized that this would be my niche within the field of architecture. At this point, I still had a desire to become a licensed practicing architect, so I applied for graduate architecture school—at the same institution—with the hopes of applying all the newfound knowledge of my public health education to my design work.

My experience in the Master of Architecture (MArch) program was rather revealing in that it appeared to me that the field did not prioritize racial and many other social considerations in its design philosophy. These topics were not discussed in my design studios or theory courses, and I became rather disenchanted with the prospect of becoming an architect. My contested attempts to inject such considerations into my studio work led me to realize that I did not want to pursue a traditional path after completing the MArch program, but that I wanted to further educate myself on the topics that I deemed critically important to the field. I decided that my next goal would be to complete a research doctorate that would allow me to synthesize my knowledge of architectural design and public/environmental health issues while emphasizing social, environmental, and racial justice. My search for the perfect Ph.D. program eventually led me to the environmental psychology program in New York City at the CUNY Graduate Center. My time in the program far exceeded my expectations and was essential in shaping me as a critical social scholar, well-positioned and well-equipped to address the psychosocial, socioracial, and sociospatial issues centered in human-environment relationships with a specific focus on architecture and the built environment.

What led you to apply to the Race and Gender in the Built Environment Fellowship?

During the last few months of my Ph.D. program—as I was finalizing my dissertation—I began to think about what my post-doctoral career path would look like. I didn’t really see myself pursuing a tenure-track position—at least not right away. I had been considering consulting, working for government or industry, or research fellowships. Several colleagues of mine, who were familiar with my particular research areas and knew that I was on the verge of completion, directly sent me information on a variety of academic openings that they felt I would be interested in. When I received an email about the Race and Gender in the Built Environment Fellowship at the University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture, I felt that it perfectly aligned with my research interests and agenda and so I applied.

For your dissertation, you focused on spatial perception, gentrification, and socio-spatial imagery in East Harlem. Can you talk a little bit about this work and research? Will your research influence your teaching goals during your fellowship term?

Yes. My dissertation research explored the sensory cues that generate spatial and social imaginaries of the built environment. In this line of inquiry, I interrogated the environmental elements—such as architectural design features and other physical properties—that are used in the development of different individuals’ environmental schema about the socio-physical and racial characteristics of various urban spaces. I specifically examined this phenomenon in the context of gentrification in Central Harlem. This qualitative and visual project demonstrated that architecture and other tangible aspects of the built and physical environment are perceived as embodying a variety of social qualities and characteristics, which elucidates the need to understand the prevalence and importance of diversity in architectural and environmental perception.

The design studio workshops and seminar courses that I will teach as part of my fellowship will be directly influenced by my dissertation. The workshops that I have created this semester will offer a unique approach to architectural pedagogy that focuses on inclusion and socioracial sustainability in design. It’s transdisciplinary in nature, so I’ll be rotating between multiple studios across the design areas in the school of architecture: architecture, landscape architecture, interior design, urban design, and community and regional planning. I will be working with the primary studio instructors to select a specific project that students will (re)design based on the content of the workshop. With this approach, I intend to apply my research at the intersection of architecture/built space and socioracial/sociospatial issues as practical and theoretical examinations and exercises that rethink both transdisciplinary design pedagogy and praxis. This will hopefully be realized in the (re)design of students’ studio projects as well as the production of student research papers.

As UT Austin’s sixth Race & Gender in the Built Environment Fellow, what do you hope to accomplish? What do you hope to challenge?

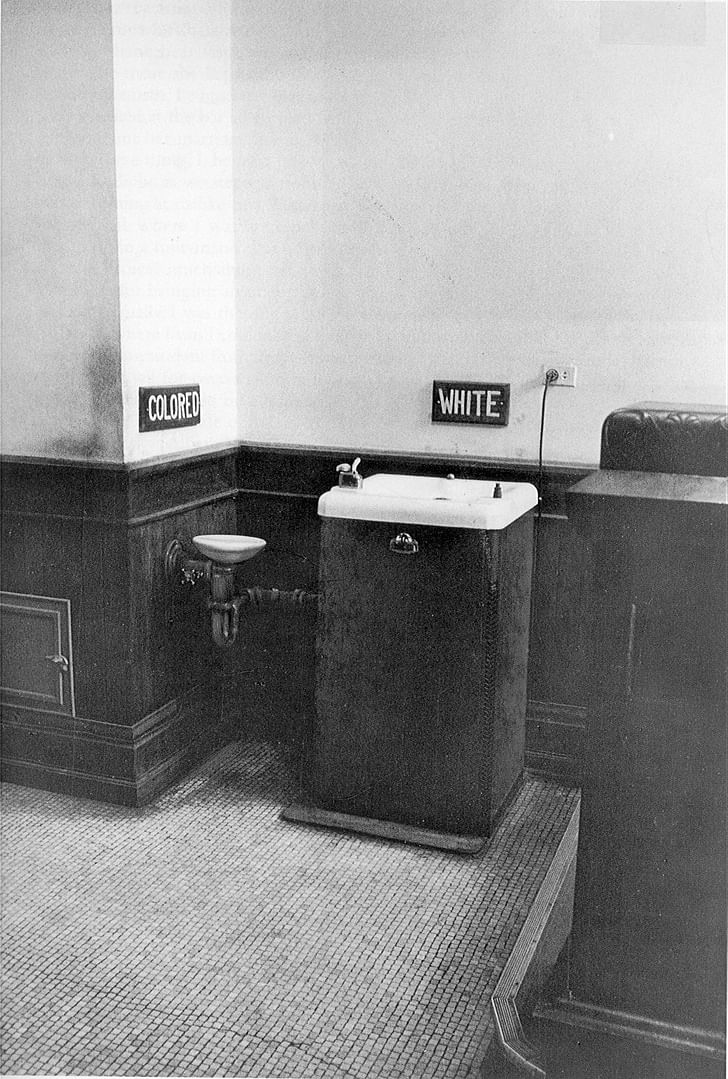

It is both refreshing and encouraging to see that the discipline of architecture has progressed tremendously in addressing socioracial issues since I first entered the field 20 years ago! Yet, there is still much more work to be done. I hope to introduce and contribute to conversations on race and space within the field of architecture by bringing empirical social science research into the equation, along with my speculative theoretical work. I hope to challenge many of the major assumptions prevalent in traditional architectural [design] pedagogy. For example, challenging the default understanding of the idealized architectural/spatial user as a White, adult, heterosexual, able-bodied, privileged male. I also hope to challenge notions or stereotypes of environmental stigma around racialized or classed architecture and physical environments.

It is my desire that examining critical socioracial issues within the production of architecture becomes so standardized and normalized that the average architecture undergrad will have received at least one course that substantially addresses these concerns by the time they are done with their first year of study.

Do you think institutions are missing the mark when it comes to educating students about socio-spatial disparities within the built environment?

Again, I’m super optimistic about the direction of the fields of architecture and urban design in addressing sociospatial issues, particularly when it comes to race-based concerns. However, I feel the work is only beginning. When I started architecture school 20 years ago, I don’t think the word “race” was ever mentioned in any of my design studios or architectural theory courses. Even over a decade ago in graduate school with advanced theory coursework, I honestly don’t recall ever discussing socioracial inequality or even reading a theorist who wasn’t White (American or European) and of course, mostly male.

Now, within the last five years to seven years, top schools of architecture in the country such as Harvard, Yale, and Columbia have initiated annual conferences and events to specifically underline critical concerns at the intersection of race and architecture. And, of course, top programs like the University of Texas School of Architecture, have created entire lines of faculty positions to recruit scholars whose work lies at the center of these issues. I am very fortunate to be one of them. I think a major persisting problem is that these conversations still remain rather ancillary to the field in general, both in pedagogy and praxis. It is my desire that examining critical socioracial issues within the production of architecture becomes so standardized and normalized that the average architecture undergrad will have received at least one course that substantially addresses these concerns by the time they are done with their first year of study. Then, in my opinion, will the mark be met.

What support or resources does a fellowship supply that would be hard to come by in another position? Why pursue a fellowship instead of a full-time position?

Well, the fellowship IS a full-time position; however, it is not a tenure track. One element of the Race and Gender in the Built Environment Fellowship that I found specifically appealing is the flexibility and ownership of one’s time. As a new Ph.D., publishing various scholarly works (journal articles, book chapters, conference papers, etc.) is critically essential for building my reputation as an expert in my field. Although this is possible and even strictly required for most tenure-track positions as well, such appointments generally come with a host of other duties and responsibilities that are a part of the tenure process. The fellowship requires that I only teach one course per semester which gives me an extremely generous amount of time to pursue my own research interests. This would likely not be the case with a tenure-track position. Also, as a two-year contracted position, the fellowship allows me to become familiar with the UT Austin community and to have access to all of its resources for faculty without the usual 5–8 year commitment expected of new tenure-track faculty. This shorter time frame means more possibility to move on to non-academic work—in industry, for example—for those, such as myself, who are not necessarily seeking a tenure-track position. Lastly, this fellowship in particular offers an insane amount of exposure and publicity that I haven’t observed even with most new tenure track appointments.

When it comes to architecture and other design fields, both education and practice most often emerge through methods of experimentation. This is a necessary component of creative fields. I love the fact that fellowship allows me to apply my conceptual and theoretical research to practical design strategies.

What are your views of the current standing of fellowships as a vehicle for conceptual exploration? Are there facets that one should be wary of?

When it comes to architecture and other design fields, both education and practice most often emerge through methods of experimentation. This is a necessary component of creative fields. I love the fact that fellowship allows me to apply my conceptual and theoretical research to practical design strategies. I am hoping that the workshops will allow me and the studios that I collaborate with to produce feasible and tangible design strategies that actively work to reduce and combat sociospatial disparities while centralizing problems of race, class, gender, and other social concerns.

For my studio workshops, in particular, I want both myself and the members of studios I will be working with to realize that there are still many limitations, challenges, and considerations in the production of architecture that will not and cannot be adequately addressed in a one-week workshop. For example, participatory design strategies, of which I am a strong advocate, will not be incorporated, although they may be discussed. I also want studio instructors and students to be wary of the misconception that the studio workshop is a “fix-all” solution to the social issues in their studio proposals. It is rather a major step in changing the conversation around how architecture and other designed spaces are produced.

For someone who is interested in learning more about architecture and environmental psychology what advice would you give them? Any specific reading you would suggest for individuals interested in this particular field of study to explore?

Not to self-aggrandize, but I would recommend one of my own articles for someone interested in learning about the intersection between architecture and environmental psychology—primarily architectural perception. I think my 2019 article “Racialized Architectural Space: A Critical Understanding of its Production, Perception and Evaluation” in the journal Architecture_Media_Politics_Society would be a good place to start.

I would also recommend two readings that have been particularly influential in shaping my career trajectory and research focus. First, a book by my mentor, environmental historian Dr. Sylvia Hood Washington called Packing Them In: An Archaeology of Environmental Racism in Chicago, 1865-1954. This book was my first in-depth exposure to environmental racism and elucidated how the built environment has historically been used as a tool for marginalization. This book is the reason I ultimately went into the field of environmental psychology. Also, the late urban geographer Neil Smith wrote a transformative book called The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City. It was the very first chapter: “Class Struggle on Avenue B: The Lower East Side as Wild Wild West” that got me interested in investigating how elements of architectural design can come to symbolize and project hegemony, especially in the context of gentrification.

In general, architectural academia and the industry have received a much-needed wake-up call these past two years. With more academic leaders like you in positions that can implement change, where do you hope the future of academia goes?

As more and more schools of architecture embrace the importance of prioritizing socioracial issues in architectural design and the production of built space, I hope that these themes become prevalent and normalized throughout their design curriculums. Coursework and conversations that cover these topics would become standard occurrences from the first semester onward.

As more and more schools of architecture embrace the importance of prioritizing socioracial issues in architectural design and the production of built space, I hope that these themes become prevalent and normalized throughout their design curriculums.

How can institutions better support non-white and marginalized designers/practitioners working towards challenging pedagogy?

Well, at the most extreme end, academic and other governmental or research institutions could create fellowships or other full-time positions that are devoted to addressing this topic—just as the UT Austin School of Architecture has done. As a basic start, such institutions can be more intentional and strategic with managing the epistemological underpinnings of a reformed pedagogy. This means expanding their “library” of references, readings, case studies, and precedents to be as inclusive and diverse as possible. Such approaches may ultimately lead to reviewing and revising the curriculum. Also, inviting activist practitioners and scholars as guest speakers, lecturers, and critics as well as showcasing their work would be beneficial.

Katherine is an LA-based writer and editor. She was Archinect's former Editorial Manager and Advertising Manager from 2018 – January 2024. During her time at Archinect, she's conducted and written 100+ interviews and specialty features with architects, designers, academics, and industry ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.