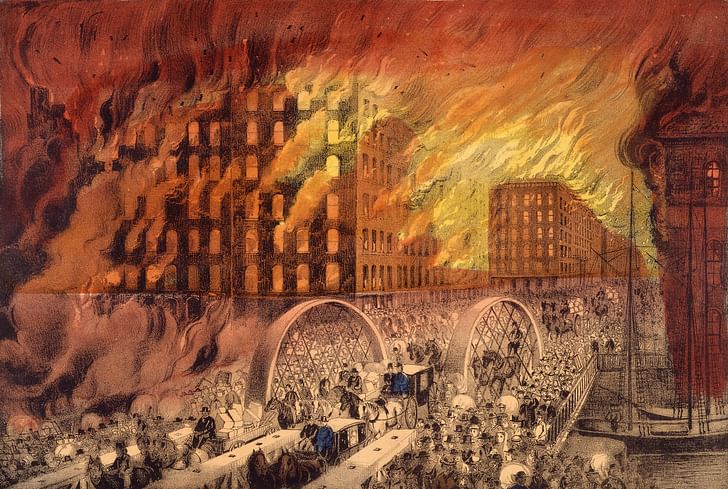

Today, October 8th, 2021, marks the sesquicentennial anniversary of the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. The three-day blaze, which killed an estimated 300 people and destroyed over 17,000 structures, is said to have been a catalyst in the history of modern design, sparking, as a direct result of the “blank slate” that was created, a revolution in the uses of different building methods, materials, and urban planning strategies around the city. From this, many of us learned, a direct line can be drawn connecting a variety of the changes that took place inside of Chicago thereafter with some of the architectural trends that shaped the development of modern cities through the end of the 20th century.

As convenient as this narrative is, it remains amongst the more dated that are still being routinely taught in design curriculums across the country. Today, we will reexamine the impacts the fire has (and has not) made using a simple two-question prompt: How has the event been misconceptualized in terms of architectural history? And, what changes can be attributed to it, given the tremendous material toll that it exacted on the community?

Jerry Larson is a Professor Emeritus at the University of Cincinnati. He authored a two-volume history on Chicago architecture that spans from pre-fire to the 1893 Columbian Exhibition. He is also the owner of the popular Instagram handle @thearchitectureprofessor that investigates examples of architecture from around the world, and another, @thearchprofessorinchicago, which uses Chicago as a lens for exploring the development of the city chronologically.

Archinect spoke with Larson about the prevailing mythology surrounding the legacy of the fire on the occasion of its 150th anniversary.

A lot of people know about the fire in some basic way, but what are some misconceptions about the event that people have which may not be altogether true, or are even in some instances misleading? Is there really a direct line between the fire and skyscraper-dominated big city skylines like we see today as gets taught so typically in school?

Jerry Larson: There are four “urban legends” about how the fire affected Chicago’s architecture that have no basis in fact:

1. The fire “wiped the slate clean” of traditional ornamented architecture, thereby, without any standing examples of the past, Chicago’s architects were freed to invent a modern architecture. Nothing could be further from the truth. Because time was money, the post-fire buildings were erected as quickly as possible, many simply been constructed from the old drawings. If anything, the post-fire buildings had more ornament, and not less, simply because fashions had changed from when many of these buildings were originally built.

2. Architect John Van Osdel came up with the idea of using clay to fireproof structures because he had buried his drawings and account book at the beginning of the fire in the basement of the Palmer House. He returned after and discovered they had survived, thereby inspiring him to develop terra cotta floor arches and fireproofing. Van Osdel has received this credit only because the first time such a system was used in Chicago was in a building he designed. This system had been patented by New Yorker George Johnson on March 21, 1871, some six months before the fire. Johnson deserves the credit for this technique.

3. After the fire, City Council prohibited the use of wood framing in the city. This is false. Once working-class citizens realized that this ordinance would have increased the cost of a new home beyond what they could afford, they told their aldermen to vote no. The only change in the building code in regards to the use of wood was the prohibition of wood balloon framing within the business district. However, this did not prohibit the use of wood floor joists that continued to be used (protected with terra cotta tiles connected to their underside) in Chicago’s early skyscrapers, until February 19, 1885, (fourteen years after the fire) when the Grannis Block (in which Burnham & Root had their office) was destroyed by fire. After this disaster, this technique was no longer used.

4. The fire brought Louis Sullivan to Chicago in search of his future. The facts say otherwise: Sullivan was attending architecture classes at MIT when the fire struck. The following year he chose to move to Philadelphia, not Chicago, in order to work in Frank Furness’ office. Sullivan would probably have stayed longer with Furness except that the Panic of 1873 eventually forced Furness to lay off the seventeen-year-old draftsman. Sullivan, with few options for employment, went back to live with his parents for free food and a warm bed. Fortunately for Chicago, the Sullivan’s had only recently moved from Boston, Sullivan’s hometown to Chicago.

The 1871 fire had no direct impact on its architecture or building construction. The 1871 fire played no role in the development of the Chicago skyscraper, with one exception.

The 1871 fire had no direct impact on its architecture or building construction. The 1871 fire played no role in the development of the Chicago skyscraper, with one exception.

It was directly responsible for the move of a twenty-year-old architect named John Wellborn Root from New York, where he had recently graduated with a degree in Civil Engineering from New York University to Chicago. Root was brought to Chicago by Peter B. Wight, another New York architect who had moved to Chicago after the fire at the request of a friend, architect Asher Carter, who needed help to respond to the demand for reconstruction. Root would form a partnership with Daniel Burnham and Burnham & Root would be the primary architects responsible for the technical and aesthetic development of the Chicago skyscraper.

To that score, what are some of the changes and impacts that it did make both materially in terms of the architectural styles that became popular in the years after the fire, and in terms of urban planning and fire prevention methods in large cities like Chicago? In what ways did Chicago "reintroduce itself to the world" afterward, and how did doing so help establish it as an architectural capital?

There were no significant stylistic changes in Chicago’s architecture due to the fire. Mansard roofs were prohibited for a brief time but made a roaring comeback a few years later. The fire had many significant impacts on the urban fabric of the loop (see below) but nothing important in terms of urban planning: Chicago was too much in a hurry to get to business to consider “urban planning.” From the standpoint of Chicago’s urban fabric, the fire:

1. Destroyed the City Hall. This was relocated four blocks south where the city owned the lot at the southeast corner of Adams and La Salle where stood a water reservoir that had survived. By erecting a temporary City Hall here, that remained for 14 years, the political and real estate center of the Loop migrated to the south. This explains why the Board of Trade was built so far away from the permanent City Hall;

2. Destroyed the U.S. Post Office and Customs House standing on the southwest corner of Dearborn and Monroe. The Federal Government bought the entire block at the southwest corner of Dearborn and Adams where it erected a larger Federal Building. Today’s Dirksen Center occupies this block;

3. Allowed the city’s wholesale merchants to relocate the city’s wholesale district from N. Wabash to S. Wacker along Adams and Monroe, thereby being closer to Union Station, where salesmen from the West detrained to order merchandise to bring back home, via the same trains;

4. All three of these events were located along Adams Street. The crowning project that established Adams as the main E-W corridor in the South Loop was the erection of the post-fire Exposition Center at the foot of Adams, on the east side of Michigan Avenue, where the Art Institute now stands. This was made possible by the great amount of fire debris that was dumped in the lagoon that sat between Michigan Avenue and the Illinois Central trestle in Lake Michigan.

To recapitulate, the 1871 fire’s most important impact on Chicago’s architecture was the relocation of Peter B. Wight from New York to Chicago. Not only was he responsible for bringing John Root to Chicago, but in 1874, following a second urban holocaust on July 14, 1874, Wight was asked by N.S. Bouton, a Chicago iron manufacturer, to invent a system of fireproofing iron structures because the insurance companies were demanding that Chicago’s building code outlaw iron structural elements or the companies would cancel all fire insurance in the Loop (which they did on November 1). While City Council ignored the Insurance Companies’ demand, private businessmen, like Bouton, had no choice but to respond. Six weeks after the second fire, Wight received a patent on September 8, 1874, for a system of applied fireproofing for iron columns. While this first application employed pieces of heavy timber, Wight quickly replaced the wood with terra cotta and invented what was soon called “Chicago construction”: an iron skeleton frame (that had been developed in New York and not Chicago) that supported its masonry fireproofing.

Therefore, we can credit the 1874 fire, and not the 1871 fire, with initiating what we call “skyscraper construction,” which is what Chicago should be known/famous for (and not for the invention of the iron skeleton frame whose American birthplace was New York).

Josh Niland is a Connecticut-based writer and editor. He studied philosophy at Boston University and worked briefly in the museum field and as a substitute teacher before joining Archinect. He has experience in the newsrooms of various cultural outlets and has published writing ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.