Refik Anadol has carved an eclectic career, rich with confluences. His work blurs the boundaries between art and science, the visible and invisible, the operational and emotional, the fleeting and permanent. The composition of this studio further demonstrates this confluence; housing artists, architects, data scientists, and researchers, drawn from 10 countries and fluent in 14 languages. Since establishing Refik Anadol Studio in 2014, the Istanbul-born artist has produced a litany of projects that celebrate, and define, the aesthetics of data and machine intelligence, from his installation at Frank Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall in 2018 to his Sense of Space exhibition at the 2021 Venice Biennale.

Archinect’s Niall Patrick Walsh spoke with Anadol in September 2021 at an exciting time for the artist: not only during his ongoing project at the Venice Biennale, but also on the eve of his latest milestone: a first-of-its-kind NFT project to be auctioned by Sotheby’s Hong Kong. In the context of our conversation, the project seems almost inevitable for Anadol; taking a cutting-edge representation of art in the machine age, from infinitely generative data paintings to AI data sculptures, and blending it with the cutting-edge blockchain infrastructure set to host that age. Arguably, this is Anadol’s greatest asset, and his greatest contribution to the built environment: an ability to take an invisible, unattainable idea beyond our everyday reality, and make it not only visible in our present day , but somehow defining of it.

Niall Patrick Walsh: Your work forms a crossroad between art, science, and technology. Can you give us an insight into how you discovered this crossroad, and how your career grew from it?

Refik Anadol: I began dreaming about architecture when I was a child. I would complain to my family about my room, asking “why are my walls so boring?” and “why am I going to the same room every day?” and “why am I seeing the same ceiling every day?” As a young mind, I found myself becoming critical of my static built environment, particularly materials such as concrete, glass, and metal. Video games also piqued my interest. I began playing video games when I was eight years old. Games were not an escape from reality for me, but instead seemed to convey a reality beyond two-dimensional space. I began wondering where the games were coming from. I was inspired by the space that had been created within a machine back at an earlier time.

Over the following years, I began speculating about alternative materials such as light and data, asking what happens when they blend, and exploring their potential for enhancing our responsive built environments. These movements and blends are gradual; they grow together not just because of technology, but because of imagination.

If an architect and artist come together, they can make the invisible flow of data visible.

In 2008, when I was at a media architecture event in Berlin, I discovered that there was an entire community dedicated to urban media facades; an academic-like group of people imagining the future of urban space. They would always say that the future of media facades were not boring screens, or monotonous, predictable advertising, but could reach beyond that. 2008 was the true beginning of my connection with media architecture. I learned about the poetics of augmented space, an amazing paper by Lev Manovich, and was particularly inspired by his view that if an architect and artist came together, they could make the invisible flow of data visible. It was an important trigger point in my imagination.

The question of “can a building dream, learn, or hallucinate” was a question I first asked in 2012, when I was studying at the UCLA Design Media Arts and while I learned about Greg Lynn’s perspectives on animate architecture. Then in 2017, my uncle was sadly diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, which propelled me into deep research about thoughts and memories; one which I continue today.

Today, the idea of projecting data onto physical architecture seems common, even inevitable. But ten years ago, this was a new concept, and one which you were the first to successfully explore and articulate. Could you take us back to the challenges of that time? And even today, do you sometimes feel restricted by the capabilities of modern technology and computing power?

I had some inspiring moments when working with SANAA’s School of Management and Design in Essen, Germany, in 2011. The building offered four beautiful cube-like surfaces which formed a remarkable canvas. At the time, we were reaching beyond the imagination of what was there on the site. We always knew there was a concrete structure with beautiful, randomly-organized algorithmic glass. But the idea that the building possessed something beyond that was a mind-opening moment. It was perhaps the first time that an artist was rendering a reality on top of a physical world that was sometimes more inspiring than the physical world itself. This requires a true collaboration between architects and artists. It also requires that the artist become responsible for reality itself, such as lighting conditions, texturing, speed, resolution, and brightness. The entire ecosystem, the reality which is created, is the pigmentation of an idea.

I do not believe you can separate physical and virtual; they are truly connected to each other purposefully and meaningfully.

Over time, game engines have been getting much better. In 2018 we were the first to use real-time graphics alongside real-time reflection, which was made possible by breakthroughs in computer graphics. My work is essentially to use virtual and physical space together, meticulously. I do not believe you can separate physical and virtual; they are truly connected to each other purposefully and meaningfully. For me, this means contextualizing the conscious model of a building, by emitting AI models onto the architecture. In 2018, for our project at Frank Gehry’s LA Walt Disney Concert Hall, an AI model read every single memory of the building, and transformed it into a media architecture. For me, the Walt Disney Hall project is a pioneer of this context. Before this, I had not seen any execution of the idea of using data itself and practicing on a physical building in real life, and in real-time.

The limitation I currently find is not with computer graphics, but with AI models. We still require neural networks to be a frozen moment, or moments, of time and space, meaning a frozen memory. However, buildings are in flux, whether it be through Bluetooth signals, or people coming and going, or memories of the events. At the moment, my team and I are exploring how we can represent something that is living, and how we can reconstruct the memory of a building, in the form of an experience or a performance. It is very challenging.

What is the role of buildings and architecture in your work? Do you draw inspiration from existing characteristics or memories in buildings you work with, or do you seek to introduce new elements or ideas from elsewhere?

Fundamentally, my work is an artistic exploration, asking can we touch our memories and dreams, and can we truly interact with something ephemeral. I believe that architecting our imagination, architecting our memories and dreams, and architecting our consciousness is as important as our physical quality of life. Architecting something we cannot touch, that we cannot even perceive unless we specifically focus and recognize it, is a very different practice from working with our everyday physical quality of life or putting certain functions to a built environment.

On every occasion, injecting a memory, or a dream, or playing with what exists, is really the playground of the imagination.

Therefore, the second approach is more inspiring to me, even from my childhood. I find it to be more challenging, to reach beyond the predictable quality of materials. I'm still very much connected to that concept. However, I also focus sometimes on what the subject building can do. An example of this is Archive Dreaming, which was a pioneering process back in 2016. I was one of the first AI artists-in-residence at Google, and we truly challenged ourselves to reimagine the library of the future. The library we created does not use the physical quality of shelves. While I love the physical world of literature, including books, reading, and touching, it is obvious to me that the future of that typology is not physical, and that post-digital architecture is not restricted by gravity at all. It is anything and everything. Designing inside the library of the future, witnessing humans and AI learning everything in front of them, is a remarkable point.

My current obsession with immersive rooms and projected infinite spaces, which has lasted now for over seven years, comes from the same idea: deconstructing corners and edges, and reconstructing a reality that is infinite, interactive, functional, but also artistic. It’s a challenging balance. It also does not need to occupy the scale of an entire building. For example, in our Melting Memories project, we created a massive media wall that stood in the center of a gallery, like a monolith. Visitors could stand in front of this sublime wall, made of millions of pixels, and watch a person’s memories be reconstructed right in front of them. Similarly, with our Quantum Memories project, I was able to construct this incredibly-scaled three-dimensional media wall at the entrance to a museum, displaying quantum memories. On every occasion, injecting a memory, or a dream, or playing with what exists, is really the playground of the imagination.

Refik Anadol Studio (RAS) sees a collection of disciplines including science, art, architecture, and media. What is the role of the architects in your team?

Much of the time, we work at the scale of a building; including immersive environments, exhibition design, massive data sculptures, or 3D printing at an architectural scale. We practice in the physical world. Even our digital projections require calculations for distances, the volume of projectors, and infrastructure for cabling, etc. Much of our process, therefore, features architectural thinking. I’m highly grateful for my team. We are 14 people, who speak 14 languages and represent 10 countries. It is a proud moment because, for me, art should be about every culture, every age, and every background. Although an intense expectation, we sometimes feel as though we are creating a new language in the world, combining mathematics and aesthetics that are felt at the same time by everyone.

We are creating a new language in the world, combining mathematics and aesthetics that are felt at the same time by everyone.

Architecture can be a catalyst for this. We have three architectural designers in our studio, engaged with areas such as physical fabrication. We are a very hands-on studio, that enjoys practicing with materials, executing functions, exhibition design, and fabrication of an idea; our designers are hands-on from beginning to end.

What is the relationship between Refik Anadol Studio, and your research wing RASLAB?

I often find that having an in-house research wing can bypass much of the bureaucracy one can encounter when collaborating with external research institutes. Without research, there is no future or imagination in a practicing partnership. We, therefore, sought to bring the idea of inspiration and research into our studio, which we could use to inspire ourselves. RASLAB is our “meta space” where we can think, imagine, discover, and collaborate with leaders in the field of practice and science. It is a very open-ended space, with no edge, no floors, and no walls. We deconstruct our identities and backgrounds and look for the uncharted, unleashed dreams that we can bring to reality. Through this, it becomes our incubator for upcoming ideas and projects.

Without research, there is no future or imagination in a practicing partnership.

Architecture, for me, is one of the topics in the lab; the discipline itself in the inspiration. While we are very unchartered, unconventional, almost unpredictable, we are still very much inspired by what has been done before. We embark on a respectful deconstruction of fundamental established concepts and disciplines in that safe environment. If we succeed, we move the idea into the real world for a final execution.

You are currently exhibiting at the Venice Biennale. Can you give us an insight into the project, and how it sits within your broader work?

When I received the email from Hashim Sarkis, the director of the Biennale, I was shocked; it was an incredible motivation to be a part of the Venice Architecture Biennale. Even as an artist, I still find that architecture is fundamental to my context and inspiration. It was a touching moment. The pandemic meant we could not create our “dream” project, but it did not stop us from imagining and speculating. Our idea was clear: how can we go beyond our memories and dreams, and instead reconstruct a space in our mind? I believe that the architectural context goes beyond steel, glass, and metal. I don’t believe that giving a particular function to a building in the physical environment is the architecture of the future. I feel that, perhaps, the future of sensing space is in our mind. But how can this space in our mind be constructed? How can we reconstruct what happens in our mind in the form of expressive space?

I don’t believe that giving a particular function to a building in the physical environment is the architecture of the future. I feel that, perhaps, the future of sensing space is in our mind.

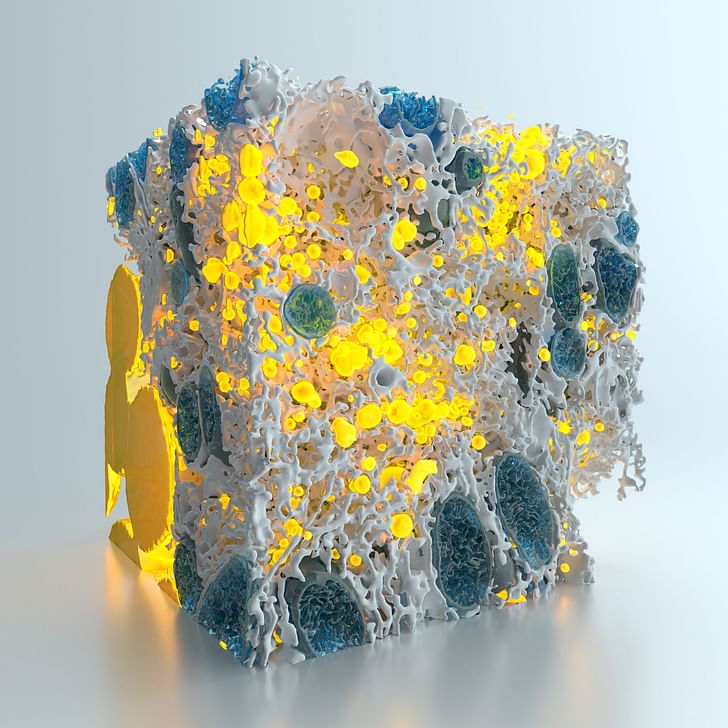

For the Biennale, we trained our AI with the unique brain activities of 4500 people. It is the very first example of using such complex data, generated by people ranging from six months to 105 years old. We were able to transform this data into an AI input, and create infinite AI Human Connectome architectures. We then 3D printed the connectomes using a robotic 3D printer and recycled PETG, to form a data sculpture. The sculpture in augmented and real-time, ever-changing during the Biennale as its gathers data from its surroundings. To achieve a project like this is a dream.

But dreaming is much easier than execution. It is not challenging to say, “I want to live the perfect day” or “I want to reconstruct my brain to represent dreams in reality.” The execution is the challenge. However, this is now becoming possible. It is one of the reasons why I maintain that there must be a connection between AI, neuroscience, and architecture; art, science, and technology; humans, machines, and environments.

Do you prefer to work within a given theme for your projects, or do you prefer to choose and build your own brief?

One of the exciting parts of teamwork is that the individual is second nature; the focus is on the idea and the experience. Therefore, creating a brief is an incredible point of interest. However, where the brief comes from is also important. In the Biennale, for example, Sarkis’ question of “how will we live together?” is an incredible question. It raises a wealth of sub-questions, such as how we will live with AI, and how we will live together with something which lives, changes, learns, and respond to us, which is not human. It was a perfectly framed, creative, inspiring question. It does not always happen like that; not every brief comes with that intellectual quality. However, in that event, I am grateful to have collaborators which can go beyond clichés, or the predictable imagination pipeline.

We try to create something which is free for everyone, open to everyone; an inspiring moment in time and space which is heavily purposed and impactful in the name of public art.

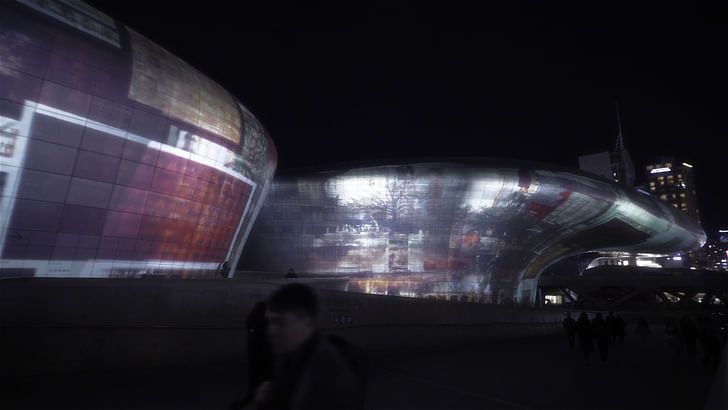

In general, I divide this thought process into three chapters. One is our internal desires and curiosities, and questions we are looking to answer as a studio. The second is an external aspiration, such as the Venice Biennale, where the context is immediately understood with beautiful motivation and energy. The third is a thinking process between us and the collaborator. For example, with Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall, or our project at Zaha Hadid’s DDP in Seoul, we have an incredible building, and an incredible archive, which exists in the name of public art. In this instance, we try to create something which is free for everyone, open to everyone; an inspiring moment in time and space that is heavily purposed and impactful in the name of public art. There is a high responsibility, high collaboration, and a new model of imagination. There are some overlaps with architecture: where you receive a brief with certain conditions for light, physical space, and budget.

What are your thoughts on the 'longevity' of art and data in the 21st century. Today, we can still bear witness to works of art and information from centuries past through the same medium as the original artist. Does the way we archive and consume data in the 21st century mean digital artwork from this era will not have as long of a life?

My first mind-opening dialog about data, including how we produce and store memories in the cloud and machines, was from the Stanford archaeologist, Ian Hodder. In 2017, Hodder donated his entire archaeological excavation data to us; a set that had been accumulating for over 25 years. During these 25 years, he and his team excavated a location in Çatalhöyük in Turkey, which was 9,000 years old. He was inspired by archive dreaming and felt this was the perfect time to bring archaeology and AI together. As far as I know, it is the first time that an archaeologist has donated their entire body of work to an AI. He said something inspiring: the physical object is not the trace, the file is the trace. The question is, how aware are we of this reality in the context of cloud computing, and the platforms we use today?

How can we be sure that we have an archaeological trace of our own data, as humanity?

It is clear that in 2000 years, when they excavate the room that I am in, they will just find my phone. There will be no meaning in it, it will just be an inanimate tool. However, from history, we learn more from what was written by the tool, not the tool itself. So, the question is, how can we be sure that we have an archaeological trace of our own data, as humanity? This is related to our earlier point about the future of library architecture not just being shelves; it means data. How do we access that? How do we see that? How do we perceive it? How do we learn? How do we remember? It is a massive new take on humanity. What is architecture doing regarding this? I am not convinced it is doing enough yet.

Today, the volume of data we produce continues to exponentially grow. How do you see your future projects evolving alongside this growth?

It is a beautiful problem. Architects deal with the life of materials, since buildings have a certain longevity. Technology is different. The nature of electronics means that a certain technology does not have a long lifespan. From a technical point of view, it is fascinating research, to stay on top of everything, to be up to speed with technology, and to truly understand the landscape of technology. Software, hardware, sensors, and pretty much anything which is technologically important becomes your palette.

I believe that architecture inspires the near future, in the same way that science fiction inspires Hollywood, and science itself.

In relation to ideas, concepts, and the imagination, I always find myself inspired by the near future. I do not tend to imagine what will happen to humanity in the coming centuries; I am more inspired by the coming decades. Where are we going? How can we use the arts to show us this near future and open the imagination to what does not exist yet? I believe that architecture inspires this, in the same way that science fiction inspires Hollywood, and science itself. We are in a similar time domain; how to look at the future together, and how to remember the future.

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.