Writer Colin Marshall takes a long look at the lasting aesthetic and architectural legacies of two of the late-20th Century’s most visionary designers: John Portman and Syd Mead. Part compare-and-contrast, part-homage, Marshall’s essay focuses on the outsize vision these two creatives projected into their work, and by extension, onto popular culture.

"The science-fiction world of Buck Rogers and the twenty-first century have not left us," write David Gebhard and Robert Winter in their Architectural Guidebook to Los Angeles. "Five bronze-clad glass towers rise from their podium base, just like one of the 1940s drawings by Frank R. Paul for Amazing Stories." The work in question is the Westin Bonaventure Hotel, one of the most distinctive-looking structures in a city once known for idiosyncratic architecture. Yet no matter how often they see it, standing as it does on a downtown hill right beside a major freeway, fewer than one in ten thousand Angelenos could name the building, let alone the man who designed it. But to those of us interested in such niche subjects as Los Angeles in film or urban redevelopment in mid-20th-century America, the Bonaventure looms large — larger, indeed, than it does on the ever taller and denser downtown skyline — as does the legacy of its architect, John C. Portman, Jr.

The Bonaventure will look familiar even to those who have never set foot in Los Angeles, provided they watch enough movies. Since opening in 1976 it has appeared onscreen with some frequency, playing a getaway driver's midnight rendezvous point, the final destination of a scavenger hunt, the site of a political assassination, the first casualty of a massive earthquake. As these roles suggest, the productions that use the Bonaventure tend to be genre pictures, often often unsubtle ones even by that standard (all of which I watched as research for a video essay on the subject). But then, the Bonaventure is an unsubtle building, Buck Rogers in its interior as well as its exterior — both of which appeared, naturally enough, in 1979's Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, among the very first films to feature either. As well as the Bonaventure would seem to lend itself to such visions of the future, however, most of the films to feature it have been set in contemporary Los Angeles.

Retrospectives of Mead's work use not just the word "futurist" but "neofuturist," as indeed do retrospectives of Portman's

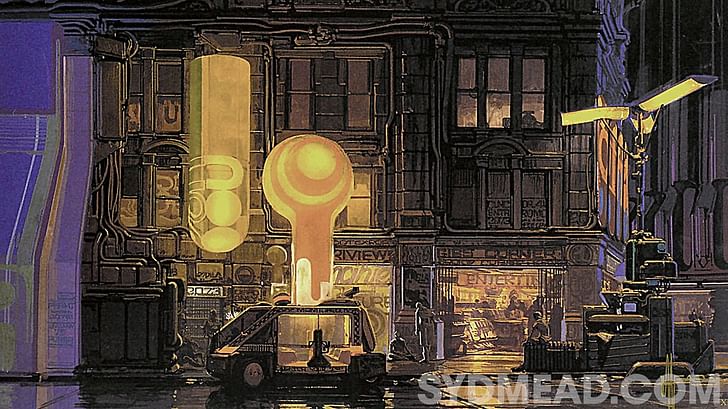

Though we haven't yet reached the 25th century, our year 2020 surely counts as "the future" as anyone in 1976 would have defined it. The real calendar has now officially passed 2019, the year envisioned by Ridley Scott's Blade Runner, which since it came out in 1982 has stood as the definitive cinematic vision of the Los Angeles to come. Notably for a Los Angeles-set genre picture (albeit an elevated one), its cityscape does not include the Bonaventure: the elements of the real Los Angeles incorporated by Scott and his collaborators tend toward the mundane, like the 2nd Street Tunnel, and even the clichéd, like Union Station and Bradbury Building, a go-to location since the silent era. But Blade Runner presents those locations as no other film had done before, stripping them of any lingering glamor and juxtaposing them against jagged skyscrapers festooned with colossal video screens and street-level warrens glowing with neon Japanese lettering.

Blade Runner owes to this mixture of credibility-straining high technology and realistic decrepitude its influence and staying power, especially compared to previous science-fiction cinema. "This is not going to be Logan's Run," Scott announced when production began — or so remembers the artist who bears the most responsibility for the look and feel of its Los Angeles, veteran industrial designer Syd Mead. Having caught the eye of Hollywood with lush renderings of the built and technological environment of tomorrow, Mead, who passed away in December 2019, once pointed out humanity doesn't "go into the future from zero, we drag the whole past in with us." Performed deliberately, this hybridization of past and future ensures that, as Mead put it in an interview a few years before his death last December, "architects love Blade Runner, they just go bonkers. When I was working on the film, it was all about, let's jam together Byzantine and Mayan and Post-Modern and even a little bit of Memphis, just mash it all together. We called it retro deco, or trash chic."

Mead's own artistic sensibility cries out for an appropriately evocative label. Blade Runner, itself described as a piece of "future noir," credits him with the title "visual futurist." Retrospectives of Mead's work use not just the word "futurist" but "neofuturist," as indeed do retrospectives of Portman's. Apart from that label, the work of the designer and the architect share an optimistic idealism about the future. That Blade Runner's setting remains a byword for urban dystopia is the great irony of Mead's career, and in life he distanced himself from the grim cinematic vision his work enriched. But that vision resonated with viewers precisely because of the contrast between the fruits of Mead's techno-utopian imagination — buildings monumental in scale and countless in number, dazzlingly multicolored lighting, flying cars — and the dinginess of the real downtown Los Angeles, at the time one of America's many pockets of urban dystopia.

It was in those dystopias that Portman did his best-known work. After the Second World War, middle-class Americans seemed to give up on downtown, decamping for the suburbs in flight from the deepening poverty and danger of the so-called "inner city." Many city centers across the United States fell into disrepair, and others, like that of Portman's hometown of Atlanta, had never fully emerged in the first place. Beginning in the mid-1960s, Portman came up in Atlanta with not just his signature style but his practice of playing the dual role of architect and developer. With the control granted him by such an unconventional (and at the time controversial) arrangement, he incorporated a variety of unusual, even ostentatious features into his projects. In the book Portman's America & Other Speculations, architect Preston Scott Cohen names among these features — or as he calls them, "tropes" — "the use of a cylindrical form," "glass elevators as gondola lifts," "transverse spatial sequences produced by escalators and ceremonial spiral stairs and extended by sky bridges," and, most midcentury of all, "revolving panoramic restaurants."

Portman owned no architectural feature more than the did the atrium, which in his hands became what Cohen calls "a kind of interiorized urban space." Or such, at least, is the apparent intent of the Portman atrium, which nearly always constitutes the core of a hotel. Portman's first such hotel was the 1967 Hyatt Regency Atlanta, one of the earliest pieces of what would become the Portman building-dominated district now called the Peachtree Center. Soon thereafter he designed another Hyatt Regency, in San Francisco, whose atrium tops what since 1973 has been the largest hotel lobby in the world. Later that decade came the Bonaventure, my own first venture into which might not have made me into a Portman fan, exactly, though it did afflict me with a permanent fascination with his buildings. I wandered aimlessly around its elevated walkways, up and down its glass elevators and circular staircases, captivated not by its artistry, exactly, and certainly not by its elegance, but by a kind of aesthetic poignancy.

Though the Bonaventure wasn't yet 40 years old at the time, everywhere the building offered reminders that its best days were already behind it: the commercial floors' many storefronts either vacant or occupied by less-than-prosperous-looking businesses; the emptiness of the ovoid seating areas suspended over the atrium; the ground-floor water features, once a seemingly irresistible temptation for the movies to knock their characters into, now the unmistakable sign of a bygone era in hotel design. Not that the Bonaventure was acclaimed even when it was new: in Jim McBride's 1983 Los Angeles-set remake of Breathless, a middle-aged architecture professor meets his young date in the lobby and casually trashes the surroundings: "You know Frank Lloyd Wright? This is Frank Lloyd Wrong." Even at the height of his success, Portman could hardly count on the support of the architectural establishment, due not just to his transgression of the boundary between architecture and development, but to the nature of his style itself.

"you can reach the TOP OF FIVE RESTAURANT and BONAVISTA LOUNGE only by taking the ORANGE elevators"

Portman's "was an architecture of futuristic fantasy, based on some simple ideas: that people liked big, open interior space, movement, light, color, and texture; that they liked simple geometric forms, which could be twisted and torqued in all kinds of ways; and that they could be induced to spend time in cities if the buildings they found there excited and did not repel them." So writes critic Paul Goldberger in Architectural Record, who also points out that the Bonaventure, as well as its scaled-up Detroit cousin the Renaissance Center, reveal "Portman’s Achilles heels as a designer: that once his buildings began to get complicated his plans were highly confusing, not to say disorienting; and that he had absolutely no interest in the street." Here the "hints" provided on an instruction sheet once handed out to Bonaventure guests speak for themselves: after explaining the color-coding of each tower and elevator ("you can reach the TOP OF FIVE RESTAURANT and BONAVISTA LOUNGE only by taking the ORANGE elevators"), the text insists the guest "not try to remember to turn right or left out of the elevator; you can get lost."

This sheet appears reproduced in City: Rediscovering the Center by William Whyte, the sociologist-urbanist best known for studies like The Organization Man and The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. City was published in 1988, when most still-unloved American city centers had yet to be rediscovered, or at least a reliable means of revitalizing them had yet to be developed. At that point Portman had been building his own attempts at a solution for more than three decades, the most recent example being the New York Marriott Marquis. A 54-story hotel-theater complex dropped into the middle of a Times Square still in its Taxi Driver nadir, it exemplifies even more clearly than the Bonaventure the form of the megastructure. Whyte devotes a chapter of City to megastructures, which then enjoyed a kind of vogue in the United States, describing them as "those huge, multipurpose complexes combining offices, stores, hotels, and garages, and enclosed in a great carapace of glass," the "ultimate expressions of flight from the street."

Though subsequent renovations opened them up somewhat, both the Bonaventure the Marriott Marquis first met the sidewalk with concrete walls, supporting the standard complaint that Portman's buildings "turn their backs on the street." So did Portman's own remarks on his designs: in his book The Architect as Developer, he writes proudly of making it possible for users of his Embarcadero Center development in San Francisco "to walk from one end of the project to the other without ever going out on the street." What fame the Bonaventure doesn't owe to the movies it owes to cultural theorist Fredric Jameson, who after visiting for a conference famously declared the building a "postmodern hyperspace" conforming to the dictates of capital rather than context. Ideally, Jameson writes in Postmodernism: The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, the Bonaventure "ought not to have entrances at all, since the entryway is always the seam that links the building to the rest of the city that surrounds it: for it does not wish to be a part of the city but rather its equivalent and replacement or substitute."

Yet Portman was an urbanist, as re-evaluations have stressed since his death in 2017, albeit an urbanist shaped by the diminished expectations of cities in his time. "To understand the Renaissance Center, you have to understand the basic situation of Detroit when we started the project," he later said of that project's first stages in the late 1960s. Checking into his hotel there, he was "told to not walk on the streets. If I left the hotel, I had to take a taxi to go to a restaurant and when I came out of the restaurant I had to take a taxi back." Amid this ambient fear, Portman's willingness to build in any city center, let alone at the scale and expense to which he'd became accustomed, must have come off between confident into foolhardy. "At the heart of my approach is an unflagging optimism," Portman admitted to esquire Esquire in 1987. But "because we’re moving from an industrial society to a technological one, most people feel a tremendous pessimism. There’s confusion, a nostalgia for the past."

Portman was an urbanist, as re-evaluations have stressed since his death in 2017, albeit an urbanist shaped by the diminished expectations of cities in his time.

Portman drew more from the past than a casual review of his work would suggest. He often recounted the life-changing disappointment of his 1960 trip to Brasília, the planned capital whose infamous monumental aesthetic — "heartless, lifeless, cold" — forced him to turn against the tenets of modernism. Back Stateside, he managed to introduce himself to Frank Lloyd Wright, who offered these words of advice: "Young man, go seek Emerson." Portman saw the Peachtree Center as "a city that will become the modern Venice. The streets down there are canals for cars, while these bridges are clean, safe, climate controlled"; he saw himself, in the dual role of developer and architect, as "the Medici to my own Leonardo." But no matter how often he looks back, the American optimist always returns his gaze to the future, and that goes double for the American optimist who launched his career, as both Portman and Mead did, in the economically and culturally triumphant period following victory in the war.

Not that it took long, in architectural time, for the defeated to rise again. By the 1980s, Japan looked set to become richer than America on the back of then-ascendant corporations like Sony, Bandai, and Honda, all of whom established relationships with Mead's design firm after Blade Runner. That film envisions a future dominated by Japan, and though not part of its Los Angeles, the Bonaventure nevertheless bears traces of that future. Some spaces look as though originally designed to cater to Japanese expense accounts: the marble outer wall of the spa spells out its services in faux-gold katakana lettering; a tour company offers brochures with details of all its southern California destinations in Japanese, and only Japanese; stacks of spare mattresses occupy some of the large, still-furnished space of a long-shuttered teppanyaki restaurant. Japan's financial bubble having burst as the 1980s became the 1990s, the imagined (and feared) Japanese future never came.

At the same time, the U.S. real-estate crash brought Portman's empire to the edge of ruin as well. Salvation came in the form of China, where Portman's name has commanded starchitect treatment ever since he built the Shanghai Centre in 1990. Transformed economically if not politically, the country demanded big, new buildings, sky-scraping declarations of its entry into the capitalist world that made statements of both ambition and control — just the kind of projects for which Portman had long drawn criticism at home. In fact his work's detractors seldom neglect to include the word "capitalism" in their indictments, often preceding it, Jameson-style, with the word "late." Whether or not the concept of late capitalism meant anything to Portman, he was by all appearances not a man to disavow his commercial instincts; nor, given his own financial stake in his projects, could he have afforded to. In his view, reviving a city meant first attracting business back into it, and to attract business required a combination of scale, safety, and spectacle, all embodied in and delivered by the megastructure.

Portman's lobbies, writes Museum of Modern Art Director Arthur Drexler in the catalog for the 1979 exhibition Transformations in Modern Architecture, "unexpectedly reintroduced significant interior space as a commercially viable entity — indeed their very extravagance has ensured their commercial success. No museum or concert hall rivals their lavish architectural incident. They now constitute tourist attractions in their host cities and are among the few buildings of the last two decades that can claim to have a genuine popular following." The architect tended to explain the choices that generated this popularity in maximally earnest terms: "Everything I do is designed to make the city a better place," he says in the Esquire profile. "What I care about most is seeing people smile." A quarter-century later, in the documentary John Portman: A Life of Building, he describes the work of his office as "playing all the chords of the heart." In Portman's words one looks in vain not just for theoretical abstraction, but also for any trace of cynicism.

Those same absences characterize the work of Syd Mead, especially his work apart from the retro-deco and trash chic of Blade Runner. Take the U.S. Steel catalogs he began illustrating in 1959, the year of his graduation from Los Angeles Art Center School (now Art Center College of Design). It seems to have been something of a blue-sky assignment, in response to which the young Mead produced, rather than utilitarian images of panels and beams, hypnotically glossy and colorful but nevertheless functional-looking visions of the world to come: impossibly low, aerodynamic sedans, one complete with gullwing doors, a chauffeur, and a giant lynx; a glass-walled suburban cross between a Case Study house and a moon base; even The Empire Strikes Back-style walkers making their hulking, deliberate way through the snow. And when Mead had occasion to render a city (or even as un-urban an environment as the Grand Canyon), he never failed to include megastructures: skyscrapers not just taller than any yet built in reality, but much more expansive as well, hinting at whole other cities hidden behind their walls.

though always built around a core of hotel rooms, often with plenty of shops, restaurants, bars, and workplaces, Portman's megastructures don't include housing.

Applied to Portman's buildings, the phrase "city within a city" has been drained of meaning by overuse: by his champions to explain what he was going for, and by his critics to underscore how short he fell of his aims. Portman always pointed up how the social life of his large private spaces replicated, indeed improved upon, the social life of small urban spaces — "Name me a public place in a city today where you can sit outdoors without anyone bothering you," he boasts to Esquire — but what urbanist today would claim that even his most full-featured, heavily trafficked American buildings feel like genuine cities? To name the most obvious shortcoming, nobody lives in them: though always built around a core of hotel rooms, often with plenty of shops, restaurants, bars, and workplaces, Portman's megastructures don't include housing. Despite his frequently professed love of downtowns, he showed little interest in living in them for more than a few nights at a time. (Apart from his own eccentrically opulent houses, his sole residential work of note in the U.S. is the 1965 Antoine Graves building, a now-demolished Atlanta public housing project built, of course, around a prototypical Portmanian atrium.)

Does anyone live in Syd Mead's cities? In Blade Runner, Harrison Ford's protagonist Rick Deckard has an apartment on the 97th floor of a downtown tower, but only because he couldn't manage to immigrate to an off-world colony and leave the Earth-bound underclass behind. Even in his paintings, Mead seldom gets close enough to his megastructures to show people at home in them: most of the activity he illustrates looks industrial in nature, and when he does render a living space, he usually places it in a detached house situated in a high-tech suburban arcadia. He always includes at least one gleaming automobile parked outside, showcasing skills developed at Ford's Advanced Styling Studio in the late 1950s and early 60s. Even if he didn't have a professional hand in intensifying it, an American of Mead's generation could hardly have resisted the allure of the automobile, both symbol and driver of so much of the postwar America's unprecedented prosperity — a prosperity whose potential for growth once seemed indefinite.

Even in his paintings, Mead seldom gets close enough to his megastructures to show people at home in them: most of the activity he illustrates looks industrial in nature, and when he does render a living space, he usually places it in a detached house situated in a high-tech suburban arcadia.

Wealth and comfort might not have felt so personally assured to Portman, who was born in 1925, eight years before Mead. His lifelong drive to keep working, developing ever more ambitious projects, and of course making money — as well as his resilience in the face of setbacks like the one that hit him at the end of the 80s — could well owe to the perpetual vigilance against financial insecurity displayed by many Americans who came of age during the Great Depression. Though a prolific artist, Mead was most admired for the quality of the imagination that shaped his art; Portman, who took up painting in middle age and made the sculptures mounted in his buildings himself, set great store by real-world productivity and the momentum of completing one project after another. But whatever the differences between their methods and motivations, their treatment of the built environment reflects similar ideals: some of Mead's paintings depict environments uncannily like those Portman would later build, at an even larger scale than Portman built them.

A megastructural complex glimpsed in of Mead's U.S. Steel catalog illustrations includes most of those tropes Portman eventually made his own: flowing water, terraced walkways, hanging greenery, enclosed skybridges. Unusually for Mead, not a single automobile is visible anywhere, a condition Portman strove to realize in his own buildings. Having attributed the decline of the American city in part to the rise of the "four-wheeled monster," he premised his designs on keeping visitors out of their cars for as long as possible. "Cities ought to be designed in a cellular pattern whose scale is the distance that an individual will walk before he thinks of wheels," he writes in The Architect as Developer. "The average American is willing to walk from seven to ten minutes without looking for some form of transportation," and "if this area is developed into a total environment in which practically all of a person’s needs are met, you have what I call a coordinate unit, a village where everything is within reach of the pedestrian."

But whatever the differences between their methods and motivations, their treatment of the built environment reflects similar ideals: some of Mead's paintings depict environments uncannily like those Portman would later build, at an even larger scale than Portman built them.

However well-furnished the coordinate unit, the pedestrian sooner or later has to leave it to get in his car and drive home — or at least he does in the reality implied Portman's work as well as in Mead's, one engineered for the suburban commuter. But then, so was the real postwar America, from whose economy and culture neither Portman's architecture nor Mead's art can be separated. At first sight of a Portman lobby or a Mead metropolis, one hears Donald Fagen singing of a "city powered by the sun," of a "just machine to make big decisions," of "perfect weather for a streamlined world," of "spandex jackets, one for everyone." Recorded in 1982, Fagen's song "I.G.Y." (which takes its name from the International Geophysical Year project of 1957-8) looks back, not without irony, on a Cold War triumphalism by then already gone sour. Portman and Mead's legacies, by contrast, evidence no ironic impulses whatsoever: if they could take the refrain of "what a beautiful world this will be, what a glorious time to be free" any way but literally, their work doesn't show it.

This earnest optimism, undergirded by business sense, still figures to a degree into the American self-image, but over the last decade or two its aesthetics have passed into the realm of "retrofuturism." The term refers to concepts of the future that clearly belong to the past, and whose appeal has thus waxed in an era without a shared image of the future to call it own. In 2015 Mead produced concept art for Tomorrowland, a retrofuturistic adventure film about reclaiming the culturally and technologically forward-looking values of the of Space Age. Produced and distributed by Walt Disney Pictures, it draws its inspiration from the eponymous section of Disneyland, the children's theme park that has stood as postwar America's representative work of architecture since it opened in 1955. It, too, derives its appeal from scale, safety, and spectacle, and when criticized as building "Disneyland for adults," Portman — given his serious concern that the users of his buildings be both comfortable and enthralled — could hardly deny it.

Disney could only expand into the theme-park business after succeeding as a movie studio; appreciators of Portman's architectural work have often praised the spatial experiences it offers in cinematic terms. Hence, perhaps, cinema's attraction to a building like the Bonaventure, the slightly-too-fast ascent of whose glass elevators feels like that of a rocket launching straight through the atrium roof. For all the impact it makes in reality, however, that dramatic transition from interior to exterior has proven difficult to capture on film; the movies have done somewhat better by the "Jesus moment" of first entering its lobby, named for the word supposedly uttered by early Hyatt Regency Atlanta guests upon stepping into that hotel's even more vertiginous atrium. They didn't know what they were in for, but then, few first-time visitors Portman's buildings do. The exteriors, opaque ("backs turned") at street level, betray nothing; the stretches of blank concrete at the base of the Bonaventure primed me for that much more astonishment at the retrofuturistic display within.

Portman's generous use of concrete in buildings like the Bonaventure, both inside and out, leads some to call them works of Brutalism. That label is one of several reflexively, and unsuitably, applied to his work: others include modernist and even postmodernist, though Portman exhibited neither an intent to rethink society nor a sense of visual humor. To their credit, his buildings have survived in a way so many from more academically categorizable movements haven't: though often dismissed as passé or crass, they don't provoke the righteous calls for demolition in the manner genuine Brutalism has. Critic Jonathan Meades calls the destruction of Brutalist buildings "the revenge of a mediocre age on an age of epic grandeur," and "the destruction, too, of the embarrassing evidence of a determined optimism that made us more potent than we have become." In its own way, Portmanian architecture also indicts the relatively complacent projects under construction in American cities today.

We live, one often hears, in the midst of an urban renaissance. Young, middle-class Americans have returned to city centers not just to work and play, but to live: this goes for the survivor that is New York as well as it does for downtown Los Angeles and even, despite its recent bankruptcy, Detroit. In a sense, the rediscovery of these cities exceeds what Portman could have imagined when he was building in them back in the 1970s and 80s. He dared to construct "mixed-use" buildings in American downtowns when few thought either one viable, and now developers can't put them up fast enough (due, usually, to punitive zoning laws, a subject for another day). But most such projects currently in fashion, typically combining condominiums above with retail on the ground, are nothing like Portman's megastructures. That's due in part to their comparatively diminutive, but in larger part to their greatly diminished ambition: they may offer housing, but they offer no conception of the future beyond marginally more convenience, inoffensive tastefulness, and "sustainability."

There is, of course, a word for Portman and Mead's shared sensibility: American.

One would naturally prefer a good building to any of these anonymous structures mushrooming up in gentrifying urban neighborhoods across the country. But one would also (especially if one happens to write professionally about the built environment) prefer a bad building, which at least has to take an aesthetic risk in the first place. In this light Blade Runner's Los Angeles looks less like nightmarish than ever: perhaps, in the words of Los Angeles Plays Itself director Thom Andersen, the film "expresses a nostalgia for a dystopian vision of the future that has become outdated. This vision offered some consolation because it was at least sublime. Now the future looks brighter, hotter, and blander." In whatever form it manifests, the sublime must overwhelm the senses, an objective that surely arises in the offices of the architects now designing the mixed-use developments of America's downtowns no more often than cinematic interiors or Jesus moments.

Goldberger credits Portman with expressing what strikes 21st-century eyes as "a vision of the future that is simultaneously audacious and quaint." The same goes for Mead, whose painted futures — and their megastructures unhindered by hostile surroundings, haphazard maintenance, and visitors confused by the floor plan — could achieve a total functionality Portman might have envied. There is, of course, a word for Portman and Mead's shared sensibility: American. No matter how distant the future into which Mead sent his imagination, it returned with vistas that looked unmistakably of the United States, even when they didn't include landmarks like Los Angeles City Hall or Churchill Downs. (Mead called these "recognition triggers," devices useful in science fiction to the extent they make viewers think, "Oh, I recognize that — the rest of it must be real too.") The oft-heard criticism that Portman's buildings fail to relate to their host cities — that they "could be anywhere" — ignores that he specialized in not Atlantan spaces, and certainly not spaces inherently of Los Angeles or New York, but American spaces.

The oft-heard criticism that Portman's buildings fail to relate to their host cities — that they "could be anywhere" — ignores that he specialized in not Atlantan spaces, and certainly not spaces inherently of Los Angeles or New York, but American spaces.

In his 1981 anti-modernist broadside From the Bauhaus to Our House, no less astute an observer of American life than Tom Wolfe considers Portman favorably alongside Morris Lapidus, the Russian-born specialist in ostentatious Miami hotels: "Probably no architects ever worked harder to capture the spirit of American wealth and glamour after the Second World War." Later Wolfe declares that Portman's "enormous Babylonian ziggurat hotels, with their thirty-story atriums and hanging gardens and crystal elevators, have succeeded, more than any other sort of architecture, in establishing the look of Downtown, of Urban Glamour in the 1970s and 1980s." Portman captured and reflected in concrete, glass, and steel — as well as copious amounts of water and greenery — the mood of an America intoxicated with its own wealth. After the rise of Japan, the Asian economies that subsequently emerged turned out to be more than buy some of that American mood for themselves.

Yet that same flamboyantly prosperous America had also become terrified of its own neglected cities. Portman's first three decades of buildings stand as monuments to the resulting desperation: stepping into one, we hardly yearn for the time when the only hope for urban American lay in replacing entire blocks with revolving restaurant-topped drive-in fortresses. But then, we may also wonder whether American architecture has lost something essential since Portman's heyday. Do today's sober, inconspicuous, responsible-looking, urban fabric-respecting developments, able neither to astound nor to offend, really merit the title of American architecture at all? Even as we point out the often considerable aesthetic and urban shortcomings of buildings like the Bonaventure, the Renaissance Center, the New York Marriott Marquis, or anything in the Peachtree Center, we should regret more deeply the passing of the spirit that made them possible — and of two of that spirit's last major exponents.

Portman and Mead, each in their own medium, envisioned the future of the American city with not just optimism but audacity, and a sense of grandeur that occasionally achieved sublimity. These qualities went along with a faith in technological and social progress that perhaps left its high water mark with their generation. Asked in a late interview about the difference between Blade Runner's 2019 and the real 2019, Mead replied, "I'm surprised that we've lost the rationality that I thought would be sustained. And I don't know what's responsible for that, what the factors are, but we no longer live in a rational social structure" — hardly a characteristic of the streamlined world he'd spent the past 60 years imagining. Portman, true to his own self-description as a man not inclined to look back, exuded sanguinity even in his last years. Portman's America editor Mohsen Mostafavi remembers the architect writing, on the page of a book he'd just inscribed, what amounted to his central principle: "THE LIFE IS GOOD."

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. He created the video series The City in Cinema and is now at work on a book, The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles.

4 Comments

Yesterday, I walked through Embarcadero Center in San Francisco. From within, you can see it for what is was - this allusion to this hypothetical city, this "futurama" if you will - the revolving restaurant atop the Hyatt Regency, once a beacon to the future is now locked in place.

Hemingway famously said that for him to write honestly about America, he had to leave it. Distance helps – it’s one of several reasons there was until late a restriction on dissertation topics being located at a certain interval in the past. The notion or writing “serious scholarship” and “the recent past” were simply diametrically opposed; today they are joined at the hip.

That Mr. Marshall should write about Detroit, Atlanta, and Los Angeles from Seoul makes sense in the Hemingway-esque manner, not that Seoul is the new Interwar Paris. And that there is much to learn from the relation of Mr. Portman’s reinvention of architectural practice to the status of American inner cities in the 1970s and 80s is clear. There are many relatively young practitioners today who operate design-build offices possibly unaware, that not long ago, it was illegal for architects to double-bill themselves as “architect-developers”. Portman changed all that almost single-handedly. He was a force.

That said, it’s unnerving to read: “One would naturally prefer a good building to any of these anonymous structures mushrooming up in gentrifying urban neighborhoods across the country. But one would also (especially if one happens to write professionally about the built environment) prefer a bad building, which at least has to take an aesthetic risk in the first place.” No, not even a little bit.

While this article looks at a certain slice of the history of American cities, its unclear what we are to learn. If we are to learn from history absent the stigma of nostalgia and the prejudice of ideological purity, it’s useful to consider Portman’s work – and the developers who followed in his wake – in relation to the architecture of the city – literally, as a book, and in its figurative sense. Not cities as collections of faceless, scaleless, objects, but as collections of urban events that accrete over time – yes, even in America.

Today, the work of Aldo Rossi, much like Robert Venturi, is often dismissed because too many react against what they built and read little-to-nothing of what they wrote (Venturi partnering with Denise Scott Brown and Steve Izenour). The Architecture of the City, (published the same year as Complexity and Contradiction, 1966) remains fundamental for those still interested in the history of cities – not only its form and image – but its anthropological substructure. Among the most useful lessons Rossi offers is the idea of the “pathological element” – that large, inert mass to which other elements (primary or secondary) cannot accrete, causing a pathogen to take hold – resisting that part of the city’s healthy development (development not in Portman’s Developer sense, but in terms of how a city is constructed over time).

Marshall proclaims: “He dared to construct "mixed-use" buildings in American downtowns when few thought either one viable, and now developers can't put them up fast enough (due, usually, to punitive zoning laws, a subject for another day).” Portman built on land no one wanted in places no one wanted to be, creating suburban shopping malls for white middle-class people in the center of once vibrant downtowns largely populated by working class people of color. The Renaissance Center in Detroit failed quickly and miserably.

Mr. Marshall’s article moves from Portman’s Vincent Korda-inspired pristine, hermetically-sealed interiors (set designs for Things to Come) to the Bladerunner post-human nightscapes as if these are good things for cities.

Portman created pathogens of immense size (absent any scale) in Atlanta and Detroit that, 50 years on, those cities continue to grapple with unhappily and with little success. "[One] prefer[s] a bad building, which at least has to take an aesthetic risk in the first place.” No, not even a little bit.

I saw the same thing and thought this is just another piece of puffery which continues to prop up the narrative that the damage modernism did was an insignificant part of the post war urban catastrophe.

"Do today's sober, inconspicuous, responsible-looking, urban fabric-respecting developments, able neither to astound nor to offend, really merit the title of American architecture at all? Even as we point out the often considerable aesthetic and urban shortcomings of buildings like the Bonaventure, the Renaissance Center, the New York Marriott Marquis, or anything in the Peachtree Center, we should regret more deeply the passing of the spirit that made them possible"

Have we not learned anything from 50+ years of devastation? Some of our best cities are full of inconspicuous responsible-looking buildings that together create a whole greater than the sum of their parts. Portman's buildings did nothing of the sort. Colossal behemoths that give nothing back to a cities people except a cold and Trumpian statement of corporate power. What aesthetic risk does a platonic form clad in a grid of glass give that a child couldn't draw in 5 minutes?

Much thanks for this, Colin. Very, very fine, so much to point out. We see the pathology behind our dreams. Then again, we realize a value in dreams that isn't necessarily nostalgic or projective.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.