Narrative, drama, and fiction have always played a key role in the production of architecture.

During the 19th Century, for example, architects like Louis Sullivan and McKim Mead & White mixed organic and formal languages to tell stories about the activities that took place within the buildings they designed, while Modernist architect Le Corbusier often worked through episodic vignettes while designing buildings and urban plans alike. In the 1980s, Jon Jerde mixed these approaches to create his trademark "experience architectures," precedents that architects like Rem Koolhaas and Zaha Hadid melded with an urban focus to create buildings that extend the street indoors and create seamless collections of spaces that blur the distinction between inside and outside.

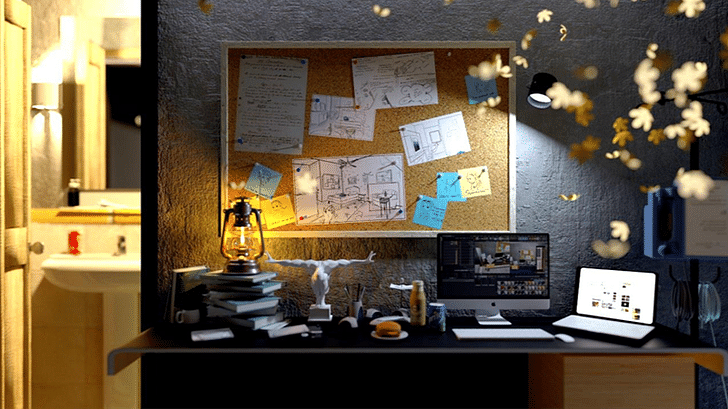

In recent years, architecture's narrative turn has largely focused on a variety of digital fronts, where virtual and augmented reality experiments, filmic approaches, and sophisticated visualizations are creating yet another genre of experiential architectural works. To highlight recent advances in this arena, Archinect spoke with UCLA Architecture and Urban Design professors Natasha Sandmeier and Nathan Su to delve into the work of their IDEAS Entertainment Studio. The studio is part of UCLA AUD's one-year post-professional Master of Science in Architecture and Urban Design (M.S.AUD) degree track that was launched by the university in recent years and represents a new horizon for architectural education.

What prompted your interest in the intersections between architecture, visualization, and media?

For better or for worse, we are entering an age where images and media representations of people, cities, and territories are often more powerful in defining what they are than the people, cities, and territories themselves. We live in a world where the line between fiction and reality is becoming less of a line and more of a gradated zone. Image-making technologies—from Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to real-time raytracing game engines—are making photorealistic synthetic imagery available to anybody with a decent laptop and some time to spare on YouTube tutorials.

This is a world of completely rendered Instagram personas, like @lilmiquela, of the entirely CGI rooms of IKEA’s catalogs, of faked viral videos, personalized media, and digital face manipulations that deliver fictions so elaborate and detailed as to be near indistinguishable from fact.

Where does the agency and responsibility of the designer, architect, and world builder lie in this strange new world?

For better or for worse, we are entering an age where images and media representations of people, cities, and territories are often more powerful in defining what they are than the people, cities, and territories themselves.

Increasingly, architecture is dabbling in narrative- and experience-based work—especially as new technologies and digital computation approaches become more widespread. How do you hope the Entertainment Studio students engage with these ideas?

Architecture is the oldest storytelling medium in the world—stories were painted on the walls of our earliest caves, for example. New media just amplifies the stuff we’ve always done: BUILDING WORLDS.

Architecture is the oldest storytelling medium in the world—stories were painted on the walls of our earliest caves, for example. New media just amplifies the stuff we’ve always done: BUILDING WORLDS.

We hope that students become adept at using storytelling as a tool to test our emotional and academic responses to emerging technological and cultural problems through parable, parody, and thought experiment.

As tools for producing fiction become ubiquitous, it is crucial that students have the skill to detect and reveal mistruths, so as not to turn our cities into enchanted forests of illusion, falsified identities, and decontextualized facts. The next generation of designers and citizens needs to be savvy and skilled at spotting chatbots, deepfakes, and personalization algorithms that filter the content we receive.

Natasha, you’ve had the opportunity to teach and work within several prominent architectural institutions. What excites you most about working with UCLA’s Architecture and Urban Design M.S.AUD program at the IDEAS campus?

UCLA AUD’s IDEAS campus is like an educational startup space; everything seems possible. The team is fantastic—it’s great to be able to work with such bright minds and amazing collaborators. It feels like we’re part of something much bigger than entertainment, and much more like we’re designing architecture culture.

As tools for producing fiction become ubiquitous, it is crucial that students have the skill to detect and reveal mistruths, so as not to turn our cities into enchanted forests of illusion, falsified identities, and decontextualized facts.

Natasha, as a practicing architect and academic, where do you see the future of architecture academia headed?

Our technologies, social structures—and therefore behaviors—are changing faster than we can keep up with. Architects, now more than ever, need not only to design for the future but also to reveal the present. If the strangeness of now is anything to go by, the future will likely be full of unpredicted risks and surprising opportunities. We believe that part of architectural academia’s responsibility is to keep up with social and cultural consequences of our technological innovations. In doing so, we would hope to uncover the unlikely indicators that might point to where we are heading, and more importantly, equip a generation of decision makers with the conceptual and technical flexibility and agility to navigate a future that is likely to be very different to the one we can already imagine now.

It’s either that, or become a battery for AI.

With visualization work, often, we only see the finished product—an animation, rendering, video, etc. What is the iterative process like for this type of work? What gets produced as ideas take shape?

What is so interesting about this kind of work is that one rarely sees the final product in any form until the very end. Until then, we only see the story through its many fragments, images, scenes, and shot lists. It’s all about workflow and having the vision to guide incredibly complex processes to tell meaningful stories.

It is all of those things and a constantly ticking number of how many days, hours, minutes, and seconds it will take to render a film in time for its screening. We’re still architects, so we inevitably work until the last possible minute.

In entertainment, the possibilities for new worlds and visions for the built environment are somewhat endless. With this concept of “limitless possibilities” across digital scales, how do you and other faculty members in the studio help students stay focused during ideation?

While our studio is defined and shaped by the world of Entertainment, we are working within a fairly narrow spectrum of design and research—in what we call RealFiction. Yes, today’s media and entertainment landscape spans a breadth of form and content never before seen, but what we’re also seeing is a massive flux in the way we tell stories today. New technologies and forms of delivery have transformed how we consume and interact with stories as we fold them into our new narratives.

Yes, today’s media and entertainment landscape spans a breadth of form and content never before seen, but what we’re also seeing is a massive flux in the way we tell stories today.

New technologies and forms of delivery have transformed how we consume and interact with stories as we fold them into our new narratives.

A (possibly unexpected) result is that, today, we are often unable to distinguish fact from fiction. AI technologies are producing fake images of people that are unshakably real, while reporting outlets and entertainment platforms feed us stories personalized to our predispositions, effectively creating as many “versions” of reality as there are consumers of media. The broadcast news industry is scrambling to maintain legitimacy in a media environment flooded with VNR’s (fake, often corporate, sponsored TV News), too often aired on legitimate news outlets. It all confirms that the line between fact and fantasy has well and truly been obliterated.

Our studio is embracing this RealFiction world and our students maintain focus by constantly measuring their speculations against the realities of our contemporary “post truth” culture. And to do that well, our films and narratives will have to transgress the real with the fictional to create a series of uncanny stories for our uncanny times.

What should we expect to see at the upcoming STRANGER THAN FICTION. Making (un)Real Worlds symposium?

We’re really excited about this weekend. We’ve invited a broad spectrum of designers and thinkers who straddle the line between fact and fiction, between the real and the virtual.

Joining us are Aaron Koblin, co-founder of Within, a leading technology company that is redefining the mediums of virtual and augmented reality; Keely Colcleugh, co-founder of Kilograph, a visualization and possibilities company specializing in the built environment; Sally Slade, who is the lead AR/VR developer at Magnopus; Amalia Ulman, an artist whose work often explores issues of identity politics through contemporary media; Johannes Mücke founder of Wideshot, a company that spans the worlds of entertainment and architecture; and Ben West, the Creative Director of Framestore who is also an architect, filmmaker and visual effects designer. We’ll be talking about the ways in which they navigate and design our RealFiction world through architecture, filmmaking, visual effects, immersive environments and experimental art practice.

How has architecture impacted the ways popular cultures are expressed materially in the built environment?

As the Eames’ proved, good selfie backgrounds?

It is our aim that students approach these tools as creative and specific ways to problem-solve when making decisions about whether to realize scenes in camera, in render, or in realtime.

What types of tools—AI, robots, digital computation, etc—are being used in the studio?

The tools we use in the studio aim to cut a cross section through professional pipelines used in the entertainment industry. Students are immersed in workflows that involve 2D and 3D compositing, motion tracking, projection mapping, dynamic simulations, physically based rendering (PBR), editing, sound design and color grading. From storyboarding and preproduction, to live action, VFX, post production and editing, students work with professional software such as Cinema4D, Substance Painter, and the Adobe Creative Suite to bring their filmic worlds to life. Also, now that game design is much more readily accessible to architects through platforms like Unity and Unreal engine, we plan to introduce the studio to real-time graphics and interactive storytelling in the spring.

We are lucky to be in a studio with four robots that can be used for camera motion control (moco), a 4K cinema camera, some serious GPUs for training neural networks and a physical workshop. We encourage the students to utilize these tools for their projects and push students to engage with technologies outside of the usual production workflow. It is our aim that students approach these tools as creative and specific ways to problem-solve when making decisions about whether to realize scenes in camera, in render, or in realtime.

Considering that many people are already addicted to their phones and that digital and immersive experiences are growing increasingly sophisticated and realistic, is there a danger that architects are helping to create alternative worlds that are too good to unplug from?

Architects have always wanted to build worlds that people won’t want to leave, so we don’t see that as a danger.

Although, a recent look into the origin of video game addictions revealed that it was first documented in 1983 (!)—a whopping 36 years ago. It was the era of games like Tron, Space Invaders, Donkey Kong, Mario Bros, and Star Wars to name a few of the big guns. By the late 1980s, addiction was a legitimate concern, and given the comparatively crude game interfaces that we’re talking about, it’s important to acknowledge the power of gameplay interaction over aesthetics. In fact, screen addiction has been a concern since TV’s became household appliances in the 1950s.

The growing chatter in the last decade with regard to our screen addictions has been less about the aesthetic environments we create but rather the tethering of our lives to our work and our friends via the onslaught of texts, pings, emails, likes...

If we, as architects, can offset that noise with compelling environments that set the stage for narratives delivering the stories of tomorrow, then we’re definitely onto something.

The growing chatter in the last decade with regard to our screen addictions has been less about the aesthetic environments we create but rather the tethering of our lives to our work and our friends via the onslaught of texts, pings, emails, likes, and the hundreds, if not thousands of notifications that blow up our phones every single day.

If we, as architects, can offset that noise with compelling environments that set the stage for narratives delivering the stories of tomorrow, then we’re definitely onto something.

Katherine is an LA-based writer and editor. She was Archinect's former Editorial Manager and Advertising Manager from 2018 – January 2024. During her time at Archinect, she's conducted and written 100+ interviews and specialty features with architects, designers, academics, and industry ...

Antonio is a Los Angeles-based writer, designer, and preservationist. He completed the M.Arch I and Master of Preservation Studies programs at Tulane University in 2014, and earned a Bachelor of Arts in Architecture from Washington University in St. Louis in 2010. Antonio has written extensively ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.