KoningEizenberg Architecture (KEA) was recently awarded the Australian Institute of Architects Gold Medal for 2019, the country’s highest architectural honor. The Santa Monica, California-based office has a nearly four-decade-long track record of fusing thoughtful programming with formal pragmatism to create a hemisphere-spanning set of eye-catching projects that inspire both architects and laypeople alike.

We recently caught up with KEA’s founding principals, Julie Eizenberg and Hank Koning, to talk about the firm’s outsider roots, the need for collective action on climate change, and the importance of designing for the sun.

You were recently awarded the Australian Institute of Architects Gold Medal for 2019, the country’s highest architectural honor. How has your upbringing in Australia informed how you design for American contexts, specifically, Los Angeles?

Both Hank and I were first-generation Australians and grew up in tight-knit ethnic communities. Those roots also made us aware of what it was like to be an outsider, a position I think that heightens awareness and influenced our creative position. Once in Los Angeles, we were outsiders twice over, and maybe that was why we picked up on overlooked threads and forms. Also, when we headed to L.A. in 1979, Australia was way ahead relative to environmental consciousness and less afraid of social equity as a community value. That, for sure, influenced how we saw and did things.

KEA also recently signed on to the international climate and biodiversity emergency pledge with Architects Declare Australia, what do you hope to achieve by joining this call?

We have always believed in sustainable design—It’s a small, vulnerable planet with limited resources. Climate change is real and CO2 emissions accelerate it. Starting out, we had naively hoped that sustainability would, like structural design, just become part of the expected DNA of a building, and that everyone would just do it and keep doing it better. Programs like LEED and others amped performance, but as an industry, we could and should do more. Current government backtracking was my tipping point to collective action.

We have signed onto the AIA 2030 challenge, support the AIA’s Resolution on Urgent and Sustained Climate Action; When presented with the opportunity to sign on to Architect’s Declare Australia, we did without hesitation.

While on the topic of Australia, KEA is currently completing the firm’s first building in the country, the Student Pavilion at the University of Melbourne. Can you describe the approach you undertook with regards to how the building blends indoor and outdoor space?

A bit of background—The student pavilion is part of a larger university initiative: the new student precinct. It includes work by many great local architects, including Lyons, NMBW, breathe, Greenaway, and EAT. It’s a wonderful collective effort.

The pavilion is the precinct’s neighborhood building: the hangout for thousands of students that live off-campus in and around urban Melbourne. It offers food, study, and small event spaces, as well as a recreational library. Its design relies on an informal spatial flow which we defined with strong indoor-outdoor gestures to reinforce a welcoming environment and inclusivity. The pavilion is the first social place students encounter when they get off the tram, and the ground floor dining and study area designed accordingly. Food vendors open inside and out, perimeter glass can be pushed back during good weather, and the precinct’s outdoor paving rolls on through the building. The “big” vertical circulation move is outside, and also designed to reinforce an indoor-outdoor connection. The vertical circulation offers a highly visible path into the building on every level via balconies and a rooftop deck designed for lingering.

KEA’s recently-completed Geffen Academy at the University of California, Los Angeles, like several of the adaptive-reuse projects you’ve taken on, seems to be more about subtraction than addition. Is that an accurate representation of the project? When working on existing buildings, how do you decide what to keep and/or repurpose?

You are absolutely correct—Subtraction is our starting point. In this case, stripping back to the bones of what was a good building gave us a head start. Designed as a staging building, the interiors had been expediently adapted for various uses over the years—we removed most of it—but the shell was in great shape, and we kept it, taking advantage of its many roll-up glass doors.

The key strategic move at Geffen was the reframing of the idea of a library from isolated destination into an open library that acts as connective tissue between instructional spaces. The idea was developed in response to the school’s interest in independent and collaborative learning, and offers an immersive rather than siloed educational environment. The open library starts at the front door and travels up and through the building’s three floors. It includes a variety of study areas, meeting rooms, and houses an unsecured book collection. It is anchored by a new sky-lit stair that brings light deep into the interior. Daylight and transparency (the classrooms are glass-faced) were the key ways we animated the design of the school, leaving plenty of opportunities for students to make the space their own.

We just completed another adaptive reuse project, the Museum Lab in Pittsburgh. There, subtraction on a decaying and distressed historic building interior—an old Carnegie library—ended up at its logical conclusion, a lovely ruin that speaks volumes. Discovery seemed like an appropriate metaphor to backdrop teen programs in art and technology.

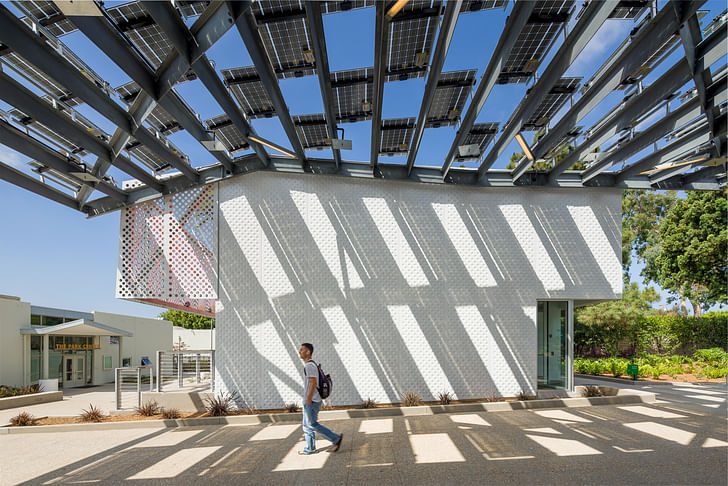

Several of your projects, like The Arroyo, El Paso Children’s Museum, Pico Library, and others, are largely defined by their relationship to the sun and solar shading; How do you position the value of these types of spaces when sharing your designs with the client? And the planning department?

We had always tried to integrate passive shading as part of our approach to design–It’s truly a Sustainability 101 tactic. It was not, however, until more people became aware of environmental value and the government (at all levels) set mandatory sustainable compliance goals that we truly got to play with the potential. We jumped at the opportunity to use shadow to create more ornament and pattern. Over the years, we have become increasingly interested in the layering of shadows, and the shape and form of the elements that generate them, the design for the El Paso Children’s Museum being a recent case in point. Passive shading is just one of many sustainable strategies. Daylight harvesting is another. That strategy is what gave form to the faceted Pico library roof.

Nowadays environmental responsiveness is well understood by most clients, communities, and cities, and employing its logic is an asset in achieving buy-in for new kinds of form-making and architectural expression. We see sustainability as a global necessity that also comes with fantastic formal opportunity.

Antonio is a Los Angeles-based writer, designer, and preservationist. He completed the M.Arch I and Master of Preservation Studies programs at Tulane University in 2014, and earned a Bachelor of Arts in Architecture from Washington University in St. Louis in 2010. Antonio has written extensively ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.