Architecture school can be a rewarding and overwhelming experience. The long hours, harsh criticisms, and competition amongst peers are only a few factors the student faces daily. And, of course, there’s the question of the material costs that come along with model building, 3D printing, software, computers, and the pile of other commodities one must acquire during their time in school. Of course, there are those students who are fortunate enough to have the funds needed to do as they desire during their academic progression. But, there are also those who can hardly afford to buy a few sheets of material. Do they just take out a loan to keep up with the more well-off students? What if their professors expect them to use an expensive material and they do not have the means to obtain them?

How do you view architecture school when you’re broke?

“Life is not easy for any of us. But what of that? We must have perseverance and above all, confidence in ourselves. We must believe that we are gifted for something and that this thing must be attained.”

- Marie Curie

As we find ourselves in an environment of intense competition, it can feel as if our work defines our status, making the urge to overspend difficult to resist. Or in other cases, we must combat the feelings of inadequacy that might stem from the lack of material quality in the presentation of our work. We see other students with seas of quarter-scale people placed on refined grass, shrubs, and landscaping made purposefully for architects. Laser-cut plexi makes up their glazing, while perfectly sanded balsawood composes the facades and form of their project.

As we find ourselves in an environment of intense competition, it can feel as if our work defines our status, making the urge to overspend difficult to resist

We might even ask our colleague how much she spent on her work and retreat in disbelief at the response. “The most I spent was $1,500,” a colleague of mine told me of his time in college, “I know a guy who spent over $8k,” he continued. $8k? And I’m sure that the project looked amazing. I mean, kudos to this guy if he can afford it. There isn’t anything wrong with someone who has higher means to put more money into their work. This is true of life outside of school, as well. I used to have an engineering professor who would always tell us, “anything is possible, it’s just a question of how much money the client is willing to spend.”

So, we aren’t dissing people who have money. Instead, what we want to discover is how we fit into the spectrum if we do not have the means to acquire what most of our class is able to. Even the $1,500 that my colleague spent is a high order for most students. During school, there those who have families and larger obligations outside of coursework, financial and otherwise. These are commendable, and common, facts of survival for many who study architecture.

“This idea of things serving many purposes is crucial to me.”

- Glenn Murcutt

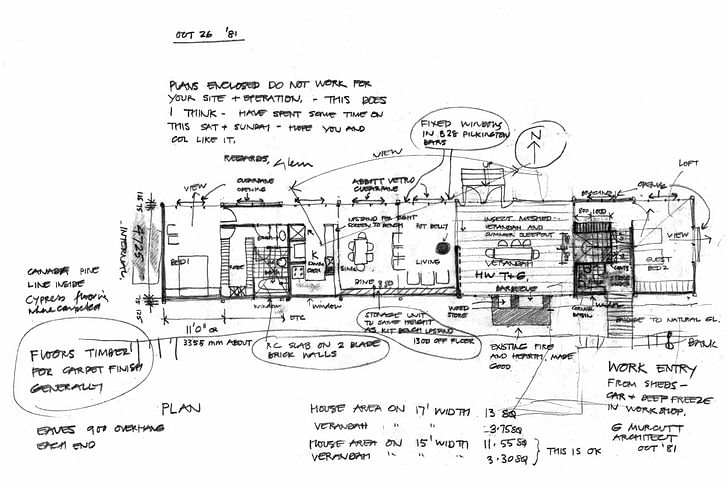

But often, in the face of great constraints comes untapped ingenuity. It’s the onset of limitation that calls for creative solutions. All the money in the world will not cure bad design: Surely, we can all think of a high-profile project that turned out to be horrendous (according to our own subjective judgment), despite its soaring price tag. And those creations that were a success; they were great not because of money, but in spite of it. Take Pritzker Prize winner, Glenn Murcutt, an architect whose notoriety comes from his masterful command of the craft of architecture, not in his ability to produce spectacles. “Because he works alone and at a small scale, Murcutt's selection cuts against the grain of...starchitects who travel the world like rock stars, turning out flashy, big-budget buildings in their signature styles,” writes Chicago Tribune critic, Blair Kamin.

The Australian practitioner works by himself, without even a receptionist. He has a waiting list of clients and tends to focus on local small projects that utilize regionally specific materials coupled with thoughtful design moves. Take the Marie Short house in New South Wales, Australia. A minimalist farmhouse, Murcutt’s client had been gathering different types of timber for a number of years. “I designed the home around these materials,” Murcutt writes about the home. A counterintuitive approach indeed: to design with what one is given rather than prescribing materials after the fact. Murcutt embraced the constraint that was placed upon him. He knew that he had the ability to make something extraordinary with what he had at his disposal.

The student architect would do well to heed to Murcutt’s example. With superior craft and design sensibility, one can transform the seemingly cheap into the thoughtfully beautiful. How does Murcutt, the sole-practitioner who uses farmhouse materials and aboriginal building methods, obtain the highest honor in architecture? Especially, when people like Frank Gehry and Zaha Hadid show up on the same list? It’s his mastery of his craft. He is a true master-builder. Many of his buildings don’t even have air conditioning. Cooling and climate control are achieved through passive methods, careful design decisions, and a deep understanding of material properties. That's very different from just slapping on an expensive HVAC system.

In school, as in life, money will always be a factor, but remember, it’s not the money that will make your work great, it’s you. Yes, money gives us the ability to achieve remarkable things (the Disney Concert Hall, for example, could not have been built on a Murcutt budget), but it is not a requirement for good work. Creativity and resourcefulness will take you far in your career and school is the perfect place to start building this skill.

“The way to wealth is as plain as the way to market. It depends chiefly on two words, industry and frugality: that is, waste neither time nor money, but make the best use of both. Without industry and frugality nothing will do, and with them everything.”

- Benjamin Franklin

During your time in school, you’ll notice two types of students. There will be the ones who have a giant bin beside their desk filled with large pieces of chipboard, foam-core, museum board, plexiglass, and balsa wood. This is only what is visible from afar. Once you walk over to this miniature landfill you will find medium and small-sized pieces of the same materials. Quite reasonably, you will ask your studio mate if he is saving these items for later. And to your surprise, he will tell you that he is not, this container of material has been declared “trash.” Perhaps he has made a small mistake on the discarded items and has deemed them unworthy of further use. We don’t know, but the obvious follow up is to commandeer this “trash” for our own use.

I remember two people from studio who would always produce the most beautiful work with what seemed to be so few materials.

Then there are the other students we marvel at. Who seem to achieve so much with so little. “I remember two people from studio who would always produce the most beautiful work with what seemed to be so few materials. It wasn’t that they were using cheap stuff, but just that they made the most of it,” a recent grad shared with me. She expressed their organization and frugality and how it didn’t diminish the final outcome of their work, in fact, they stood out because of how creative they were. Sounds a lot like the onset of the qualities that Murcutt embodies in his practice.

“Scratch the complaining. No waffling. No submitting to powerlessness or fear. You can’t just run home to Mommy. How are you going to solve this problem? How are you going to get around the rules that hold you back?”

- Ryan Holiday

Let’s embrace our roles as designers and the inherent creativity we have within us. Sure, you may “just be a student,” but you are in an environment to learn, grow, and become better. Financial strains are without a doubt a giant drag, there is no discounting that. Instead of wallowing in its crappiness, let’s use that energy to problem solve. As Ryan Holiday asks in his bestselling book, The Obstacle is the Way, “Does getting upset provide you with more options?” It doesn’t. We are in the circumstance that we are in, and it’s up to us to do something about it. If all you have is a pile of scrap materials, start thinking about what you can do with it. How can you design around what you have, just as Murcutt did with the Marie Short house?

There are endless possibilities, and some are tougher than others, but in the end, if you really want to make something happen, you will find a way

And, of course, we cannot always avoid the class requirements, so if you must have the better material, what can you do to obtain it? How can you get the money to buy what you need? Perhaps it’s better time management at school so that you have time to work. Or less social time to make it to your second job. There are endless possibilities, and some are tougher than others, but in the end, if you really want to make something happen, you will find a way. And as a creative person, you have greater powers than just sheer will at your disposal. Design a solution for yourself. Iterate and see what works and what doesn’t. As Holiday says above, “How are you going to solve this problem? How are you going to get around the rules that hold you back?”

So you’ve embraced your creative powers and are ready to be resourceful. That’s great, but you probably need some actionable starting points. Here are a couple from some recent architecture graduates and professionals of varying experience levels:

Go dumpster diving at the wood/metal shop or even in the trash cans in studio. As the saying goes, one person’s trash is another one’s treasure.

At the end of the year when studio is cleaned out, a lot of students leave behind good materials. This is similar to the previous point; think ahead to your next year.

Don’t be afraid to use “informal” materials. Instead of buying expensive grass for modeling, for example, what else can you use to achieve the same effect? (turf from Home Depot, spray painted cotton, etc.). Craft is key here.

Don’t throw away your scraps!!!

It’s only important what people can see in your presentation. You don’t need expensive material as the interior support in your models. “Out of sight, out of mind.”

Work a PAID internship a couple of times a week, if you can.

Work at school, preferably in jobs where you can complete assignments while you work (computer lab tech, woodshop, fabrication lab, etc.)

All the normal budgeting stuff: Don't eat out too much, or overspend on materials (always having a surplus), etc.

Have a written budget (i.e. $100 for materials every two weeks, $25 for eating out each week, etc.). Remember: with constraint comes creativity. Most of us don’t have an unlimited supply of money, but many of us act like we do in architecture school. 10 years from now you probably won’t care about your $500 3D print, so maybe that money could be put to better use on something else.

You can use materials from previous projects. It’s controversial, but when you literally have no money for materials you have to do what you have to do. Just photograph your work before you destroy it.

If anyone else has more tips or pointers for struggling students in school please leave your advice in the comments!

Sean Joyner is a writer and essayist based in Los Angeles. His work explores themes spanning architecture, culture, and everyday life. Sean's essays and articles have been featured in The Architect's Newspaper, ARCHITECT Magazine, Dwell Magazine, and Archinect. He also works as an ...

5 Comments

Good piece.

Good advice. We raided the local fabrication shops for plexiglass (all kinds of polycarbonate was had from a fabricator who loved us reducing their trash -and treasuring it) and wood (millwork shops tend to have a wide variety of woods -often expensive ones-); chipboard/cardboard could be had from art and furniture stores (from their packing). The schools also had staff that stored tools from past students that could be passed down, back in the days of drafting boards and maylines that saved some students a good month's rent. There's also bartering: in many schools the undergraduate studios end a week early, helping out a grad student can be good $ and also a way to learn and potentially inherit a trove of valuable tools/books/materials.

last year's college posters.

Cardboard...from everywhere. Talk to people in the maintenance staff to get the better boxes.

Samples from product reps.

Never use plexiglas unless nec. Way too expensive! Dont build glass unless you have to.

Cereal boxes...never hard to find at a college.

I always encouraged my students to do it as cheaply as possible without hurting the idea. Any professor that requires virgin materials, question!

this is why "hard" architecture education is essential -- to show students how to draw, build and use materials economically and right for context. too much now is oriented towards "soft" practice -- theory, narrative, politics, and glorified branding -- when economic, humane architecture is growing more scarce. luckily saw a lecture by Glenn Murcutt early in my schooling so it always seemed like the way to go.

I don't dispute most of this article, but must point out that his engineer's drawings override his own and describe a lot of the surface finishes. Also, back in 2001 when I asked him, he told me his per square meter rate was AUD$4000... double what clients on a budget were getting their buildings for and quadruple the cost of mass produced houses.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.