For over 250 years, African Americans in the United States endured the bondage of slavery, a cultural, political, and economic regime that exploited their forced labor in order to clear land, harvest crops, and build America’s cities and towns. Under these conditions, human beings were viewed as a form of property and as a source of free labor. Individuals and families were bought, sold, torn apart from loved ones, and subjected to untold violence and exploitation, an existential debt that has yet to be properly or meaningfully reconciled.

Amid this historical context, Horace King, a man born into slavery on a South Carolina plantation, rose to become a prolific architect, real estate developer, and Alabama state legislator. Educated and trained on the jobsite as an engineer and contractor, King built bridges, courthouses, and industrial facilities across the southern United States.

This is his story.

Horace King was born into slavery in 1807 in an area now known as Chesterfield County, South Carolina. Working in the town of Cheraw, an important but small settlement on the western bank of the Pee Dee River, King, a mixed-race man with Native American, African, and Caucasian ancestry, received training in bridge building and design while working for the man who owned him, John Godwin. Godwin worked as a speculative home builder and bridge contractor in the region, and often lent his services, as well as the King’s labor, to work on the plentiful and sometimes lucrative construction projects taking shape in the rapidly-developing area.

It is believed that King received some of the most important training of his career when Godwin and King apprenticed under the noted architect and bridge builder Ithiel Town. One of the first professional architects in the United States, Town was well-known for his Federal and Greek Revival building designs on the East Coast. Town was also an inventive bridge builder, and in 1824, Town came to Cheraw to build a new bridge over the Pee Dee River so that the federal post road connecting Washington, D.C. with Atlanta, Georgia could be extended through the city.

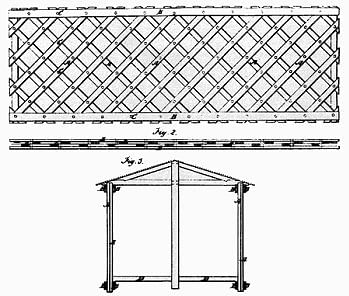

Four years prior to his arrival in Cheraw, Town had been granted a patent for an efficient and ground-breaking design for a wooden lattice bridge made up of sawmill lumber planks held together by wooden pegs. The innovative lattice truss design revolutionized bridge construction in the United States due to the fact that it could be built quickly using relatively unskilled labor, and because it performed well under long-span conditions, alleviating the need for extensive stone arch piers. The design, innovative then, became ubiquitous over the years across the South, ushering in the long tradition of covered wooden bridges that continues into today.

While it is unclear exactly how King, who was only about 16 years old at the time, was involved in Town’s bridge-building plan, King picked up the truss design and used it repeatedly throughout his career afterward.

In 1832, King and Godwin moved their families to Columbus, Georgia, where they had been awarded a bid to construct a bridge over the Chattahoochee River connecting Columbus to Girard, Alabama. That year, Alabama took over land in the area that was originally owned by the Creek Indians. It fell on King and Godwin to build a bridge connecting Columbus on the eastern banks of the river with Girard on the western side, where the newly-acquired lands could be settled by land-hungry Americans. Using hand tools, lumber planks, mules, and granite blocks, King supervised the design and construction of a 900-foot covered wooden bridge that marked the first crossing over the Chattahoochee River in the area. The bridge, built using enslaved laborers, is the first known structure officially credited to King. A few years later, King also built the first railroad bridge to span the Chattahoochee just down from the original wooden crossing. The railroad bridge, a single-span, steel truss crossing, is raised on granite piers and still carries train traffic today.

As King completed the twin spans across the Chattahoochee River, he and Godwin—King remained enslaved despite his growing professional capabilities and prominence—moved across the river to Girard, where the two developed real estate and built many of the town’s original homes.

Over the following years, Godwin and King developed a successful bridge building business, completing a new 540-foot crossing south of Columbus at Irwinton, Alabama, and another at West Point, Georgia. They eventually built more bridges in Tallassee, Alabama, and, potentially, according to the Alabama Heritage blog, at Florence, Alabama, as well.

The ventures undertaken by King and Godwin were not limited to bridge-building, however, though it is reported that King’s skill in bringing together freed and enslaved workers, as well as his experience and technical expertise, contributed greatly to the success and longevity of the bridges he designed and supervised. Because he specialized in such innovative and necessary infrastructural linkages, King was known by members of the business and political establishment throughout the south as a respected builder, a skilled designer, and as a competent and reputable contractor. Through his bridge building work, King became an expert in long-span structures, in general, and used this expertise to help Godwin complete construction projects that included large homes, courthouses, and industrial facilities. It is reported that King worked on the home of United States Senator Seaborn Jones, a job that brought more work to the architect. King would go on to design and built a corn-processing mill at the senator’s City Mills project in downtown Columbus, for example.

In 1841, after the original 1832 Columbus bridge washed away in a devastating flood, King and Godwin set off to rebuild the span in record time. By repurposing and restructuring elements of the original bridge that had been salvaged after the flood, King was able to restore the connection between Girard and Columbus quickly, much to the delight of the area’s political and business leaders. As a result of this achievement, King was taken to Ohio, where he could enjoy life as a free man. Because Alabama had state laws on the books that forced freed slaves to leave the state upon emancipation, King was forced to live in the free state of Ohio for a period of time. While in Ohio, it is rumored that King attended Oberlin College, the first college in the United States to admit black Americans. He also joined the local Masonic lodge, an affiliation that was not allowed back in Alabama.

In the 1840s, after King returned to Alabama, and servitude, his career took off further. He was allowed to marry a free woman of color named Frances Gould Thomas, an uncommon arrangement that, due to local laws, meant that the couple’s five children were born free, according to American Antiquities. In the following years, King worked as an independent architect and construction superintendent while completing bridges in Columbus, Mississippi and Wetumpka, Alabama. He eventually met the slave-owning attorney and entrepreneur named Robert Jemison, Jr., who commissioned King to work on bridges across Mississippi and Alabama.

In 1846, King was able to purchase his own freedom from Godwin. That year, Jemison, an influential legislator at the time, mustered support to grant King his freedom a second time, now by an act of the Alabama legislature that included a special caveat: The decree created an exception to existing laws and allowed King to remain in Alabama as a freed man.

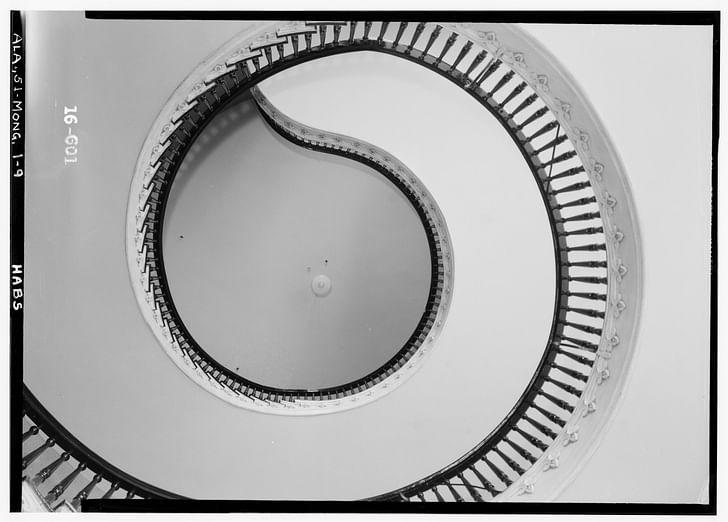

Three years later, the Alabama state capitol burned down, and King was one of the many architects and builders hired—and paid—to oversee the construction of a new capitol building. There, King oversaw the construction of shoring for the capitol dome and created a project that is among his most beautiful works, a floating central staircase located at the heart of the new capitol building. To create the levitating stair, King relied on his knowledge as a bridge builder. Using a canitlevered stair system, King deployed radial framing members to create a self-supporting stair where structural loads were transferred from the top of each riser to the tread below. As the framing fans down in a single helix spiral, the loads are resolved incrementally until they reach the atrium’s masonry floor. The structure, recorded in the Historic American Building Survey, is documented by the Library of Congress and exists into today as one of the most prized works of architecture in Alabama.

Despite these incredible achievements, the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1860 would alter everything.

For one, despite being a devoted Unionist, King was conscripted by Confederate forces to aid in the war effort. King helped build naval vessels in Columbus, for example, while also engaging in other tasks. As the war ended, Union soldiers destroyed many of King’s bridges, including several of the bridges he built in Columbus. After the war, King rebuilt his Columbus crossing for a third time and went on to more success as a businessman and designer. He even served as a two-term Alabama state legislator.

Eventually, King resettled in Georgia, where he formed the King Brothers Bridge Company with his four sons, each of whom would go on to become a successful builder and designer in his own right, Black Past reports. King died on May 28, 1885, and was lauded in the state’s newspapers for his many achievements.

As the 1995 documentary, HORACE: The Bridge Builder King explains, with his notoriety was on the rise in the 1990s, King was posthumously inducted into the Alabama Engineers Hall of Fame.

Despite their incredible age and relatively impermanent construction methods, many of King’s works live on. Though many of the bridges have been demolished over the years as roads became highways and towns underwent urban renewal, some, the Bridge House in Albany Georgia, for example, remain and are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. King’s last remaining covered bridge by King is located in Red Oak, Georgia, is also listed on the National Register, and can be visited today.

For more information on Horace King, see J. David Dameron's book, Horace King: From Slave to Master Builder and Legislator.

Antonio is a Los Angeles-based writer, designer, and preservationist. He completed the M.Arch I and Master of Preservation Studies programs at Tulane University in 2014, and earned a Bachelor of Arts in Architecture from Washington University in St. Louis in 2010. Antonio has written extensively ...

1 Comment

Nice work, especially the stair.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.