In our creative endeavors, we are often seeking to push boundaries, to challenge the status quo. As creators, we want to introduce something fresh and new to the world. We hope to express ourselves in authentic ways. In a studio setting, we talk about innovation, but how do we go about that? How do we get outside of the box and separate ourselves from the majority? It’s an interesting question, one that I don’t think has any prescriptive kind of answer. We are all already extraordinarily creative, after all. Nevertheless, there are countless examples for us to explore to help us establish some principles to guide our thinking. This article is one such exploration of how we might approach pushing the envelope in our work.

One day, during a softball game with some local friends, Bobby Colomby, the drummer for Blood, Sweat, and Tears, noticed an attractive young woman playing in the outfield. They both got to talking and naturally, Bobby asked if she was married. She was, she replied, to the greatest bass player in the world. Shortly after, the woman’s husband came up and introduced himself. “I understand you’re the greatest bass player in the world?” Bobby says, sarcastically to the husband. “Yeah, I am,” the husband replies. At this point, Bobby’s arrogance kind of swells up, “Well, why don’t you go get your bass and just play a little bit.” The husband got his bass and blew Bobby Colomby’s mind. He played the Charlie Parker classic, Donna Lee, a song written for the saxophone, on bass!

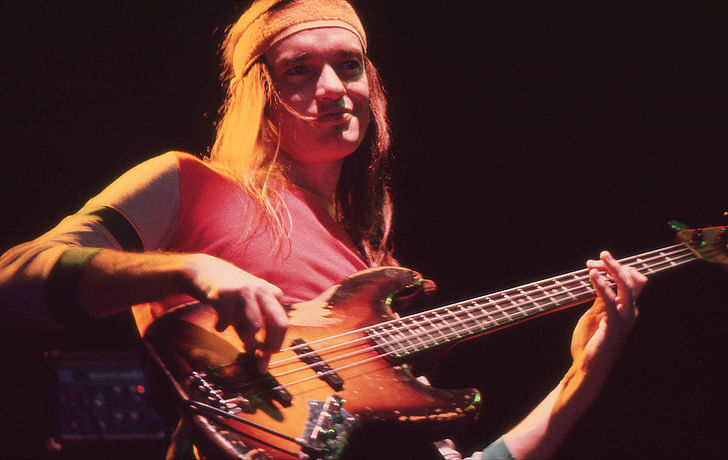

The woman Bobby met? Her name was Tracy Lee. Her husband? His name was Jaco Pastorius, one of the greatest bass players to ever live.

After Bobby heard him play he immediately offered the ambitious musician a record deal, marking the start of young Jaco’s fruitful career. In the bass world, Jaco Pastorius is considered “the Jimi Hendrix of bass.” His revolutionary style on the instrument was unprecedented in his time and turned a new page in the annals of musical achievement. Traditionally, the electric bass, in Jazz, was an instrument that held the band together. Along with the drums, the bass player keeps the ensemble in time and on point. If you listen to jazz classics like Giant Steps or Autumn Leaves, you’ll hear that impressive walking bass line, outlining the chord changes for the group and keeping everyone in sync. Or sometimes the bass can lay down a nice groove. You’ll find this in hits like Chameleon by Herbie Hancock, it’s a beautiful thing (but again, I play bass myself, and I love Jazz). Jaco didn’t do away with the traditional aspects of the bass guitar. Instead, he built on it.

If you listen to his famous song, Portrait of Tracy, you’ll hear his innovative use of harmonics, which were used for tuning guitars. No one ever thought to make music out of them — Jaco did, and it became a foundational part of his sound. He was a pioneer on the fretless bass as well, establishing an iconic tone that everyone wanted to emulate, he was, by all accounts, a musical genius.

But what did Jaco do so excellently that elicited the response he got from Colomby? It wasn’t just that what he played was technically difficult. He took a popular jazz song that everyone knew and presented it in a new way. He took something familiar and transformed it into something new. He might not have gotten the same reaction if he just played an original song that he wrote. While still being technically impressive, it would not have been as astounding as something his listener could relate to. Jaco understood this and knew that anyone who heard him play this classic song on his fretless electric bass guitar would be mind blown — that understanding kick-started the rest of his life in music.

When I think of this in terms of architecture, taking something familiar and reintroducing it in a new way, I think of an early Frank Gehry. Like any great creator, people either love him or hate him, but regardless, there is no doubt he revolutionized architecture as an expressive medium. I’m thinking specifically of his early use of “junk” in his work. Chain Link and corrugated metal were two materials that had their predetermined applications. Gehry forgot about all of that. He implemented the metals in ways unfamiliar to architecture. So much so, that the remodel of his personal residence launched an extraordinary career (there seems to be a theme developing). Gehry is quite arguably the epitome of the starchitect.

Look at the Seed Cathedral by Heatherwick Studio. The eccentric designer took one of Mother Nature’s most precious commodities, the seed, and introduced it into something remarkably striking, presenting something we all know in an innovative way. Early on, we learn that there are many approaches to the creative process. Our initial question was how we might separate ourselves from the majority. Both Heatherwick and Gehry are distinct in their own right. This comes from a combination of experience and boldness, something in line with what Picasso meant when he said to learn the rules like a pro so that you can break them like an artist. Innovation comes with experience.

“If I have seen further than others, it is by standing upon the shoulders of giants.”

- Sir Isaac Newton

Austin Kleon’s primary premise in his bestselling book Steal Like An Artist is that all creative work builds on what came before. Nothing is completely original. He’s right on the money. Look at any great pioneer throughout history, and you’ll find one thing — they always built on the work and ideas of those before them. It’s in seeing what everyone else sees in a fresh new way that “originality” surfaces. Thomas Edison didn’t invent the light bulb. He made a better version of the incandescent lamp, which many before him had devised, but with unbearable inefficiencies that made them difficult to integrate into the broader population. Edison believed he could recreate the light bulb, but he did not invent the concept, it came before him. This is quite liberating, to know that those we look to for inspiration were mere mortals. Their genius came from an understanding of their field coupled with an imagination and boldness to try something new.

Thomas Edison didn’t invent the light bulb. He made a better version of the incandescent lamp...

Think of the French gardener, Joseph Monier. Frustrated with the fragility of his clay flowerpots, he started to experiment with concrete but soon found that it also was too brittle for him. As Monier furthered his explorations, he tried incorporating metal mesh into the pots in hopes of strengthening them. And we all know what he got. A flower pot that was not only compressively strong but that also took advantage of the embedded metal’s tensile properties. He had created reinforced concrete. Monier expanded on his discovery, and soon reinforced concrete became an invaluable tool for engineers and builders. The rest is history.

When this frustrated florist decided to find a way to make stronger pots, he did not try to materialize a new idea out of thin air. He was not the first to experiment with reinforcement, and concrete had already existed for thousands of years. He merely took what already existed and experimented with it. I’m sure Joseph Monier was not the only gardener who was frustrated that his ceramics kept breaking, yet he was the only one who solved the problem successfully. He separated himself from the majority. It seems the only attributes he possessed to do so was a willingness to experiment, an ability to imagine something different, and a belief that he could figure something out.

In our ambitions in architecture, the path is one of discovery. As we explore our curiosities, experiment, and build on our experience, new ideas begin to arise. The question we must ask ourselves is if we have the boldness to take a chance and try something out. I love Elon Musk’s famous line: when something is important enough you do it, even if the odds are against you. Sometimes, things are just worth giving a shot, even if it leads to nothing. And if we’re lucky, those explorations may lead to something beautiful. How many accidental breakthroughs have there been in our past? (penicillin, the microwave, Velcro).

One of the most valuable things we learn in school and professional practice is the value of precedents. When we are first starting out, we sit there wondering how we will create something from nothing, but soon we learn that something always comes from something else. One of my mentors would astonish me with the types of ideas he would come up with. The team would brainstorm, and he would always have the perfect thing to get us started, the depth of his ideas seemed limitless. And then I began to observe that those more experienced architects I’ve looked up to have built up a vocabulary that allows them to fluidly create at a level far beyond the norm — I’m talking people with decades of experience here. Remember Picasso’s quote? They were at a point where they could break the rules and think fluidly. My mentor had reached this point in his career. It’s what we should all strive towards.

I’ll end with something Sam Esmail, the creator of the totally awesome TV series Mr. Robot, said in an interview about his influences for the show:

“I rip off every movie and TV show I’ve seen in my entire life.”

If you’ve seen Mr. Robot, you’ll know what he is referring to. The show unapologetically pays homage to films like Fight Club and many others. It’s what makes it so great. I do this in my writing. Take this article, for instance. It’s an exact copy of the format that Robert Greene and Ryan Holiday use in their books, two of my favorite authors. In some of my previous articles, I’ve copied the style of Nassim Taleb, the author of The Black Swan.

I’m still building my vocabulary as a writer and adopting these different voices, trying to learn from them, and how they fit into my personal style, helps me grow tremendously. It’s the same in design. Let’s start embracing and celebrating one another. And when ideas begin to creep up, introduce them to the world with boldness. I think the result can only be a bounteous one.

Sean Joyner is a writer and essayist based in Los Angeles. His work explores themes spanning architecture, culture, and everyday life. Sean's essays and articles have been featured in The Architect's Newspaper, ARCHITECT Magazine, Dwell Magazine, and Archinect. He also works as an ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.