The tradition of architects experimenting with new typologies and forms on college campuses is one that goes way back.

Whether considering Frank Lloyd Wright’s 10-building collection of Usonian structures at Florida Southern College, Venturi-Scott Brown’s technological-contextual works at UCLA, Minoru Yamasaki’s elegant and stately Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton, or Frank Gehry’s shape-shifting Stata Center at MIT, college campuses have often provided fertile terrain where thoughtful, brand name designers and open-minded clients with unconventional program needs can come together in the pursuit of bold design solutions.

REX’s forthcoming Performing Arts Center at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island is no exception.

New York City-based REX is doing many, many things with their Performing Arts Center project at Brown University.

For one, the firm is singing a new tune for complex, creatively-driven ground-up buildings, specifically, when it comes to ensuring that their work is delivered on-time and on-budget.

To do so, REX is working hand-in-glove with contractors, fabricators, suppliers, and the university via the so-called Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) model, a collaborative approach for architectural production that positions design, construction, and fabrication according to rigorous and overlapping schedules in an effort to arrive at collective, expedited decision-making.

Initiated due to the fact that the partially-submerged building will be built with two levels encased by dense bedrock, the IPD model promises to allow the construction crew to begin excavation work on the site aimed at clearing the tough-to-remove bedrock as other elements of the design are hammered out, for example, saving time and money later on in the construction process. The arrangement also provides guardrails for the building’s design, locking-in key infrastructural and programmatic decisions while allowing the architects to pursue more open-ended spatial and construction ideas from a cooperative, synergistic position.

PAC, as REX principal Joshua Ramus explained in a recent Archinect Sessions podcast, is among the largest one-off large cultural buildings in the country being developed under the IPD model.

According to Ramus, the client had two options: “Build four different venues, or a single venue that could, through automated and manual flexibility, transform among five potential configurations.”

But the building, which takes the form of a scalloped aluminum cube sliced by a long horizontal glass blade, is more than a tightly-wound feat of organizational energy. Shaped according to the physical and experiential needs of the five different performance venues that will be contained within, the reconfigurable building represents a step forward for another age-old architectural obsession: flexible design.

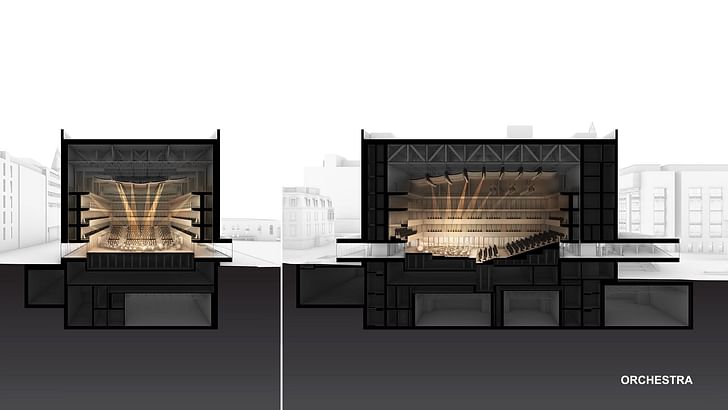

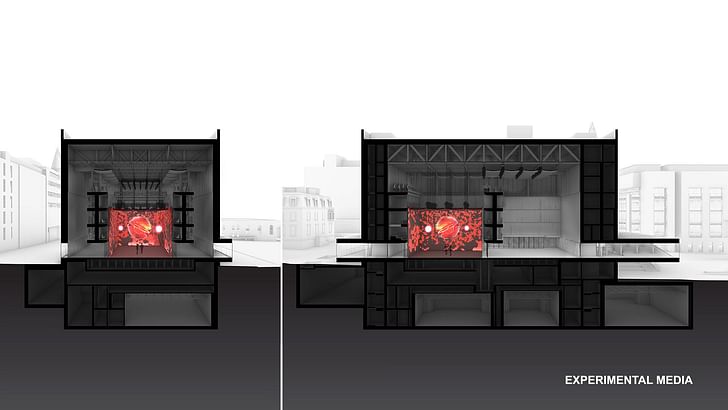

As a diagram, the building’s design is shaped around the physical and acoustical requirements of the performance spaces it is meant to contain. Included in that mix, for example, are configurations for an intimate experimental performance venue and a 500-seat orchestral arrangement, as well as several others. The latter space, designed for the Brown University Orchestra, a 105-piece orchestra ensemble that is often joined by an 80-person chorus section, marks an evolution of the medium-sized campus concert hall type in its own right, while the collection of other possible configurations will, according to the architect, position the university as a “place where performance is research and research is performed.”

But the building, with its choreographed mix of automated, manual, and digitally-controlled transformable elements, is more finely tuned and specific than what might typically come to mind when considering movable architecture. Unlike previous eras of push-button design, where the ability to do “anything” is emphasized conceptually but rarely realized physically, each configuration of REX’s PAC is designed as one of several “exceptional presets” where the logistical requirements necessary to achieve each transformation lead the overall design. This perspective is one that has been developed by the firm over the last 15 years, building on REX’s previous experiences with performance venue design.

“you see time again, in all different kinds of typologies, buildings that can supposedly transform into anything and therefore, never do anything.”– Joshua Ramus

Back in 2004, Ramus, then principal-in-charge at OMA New York, helped design the Wyly theatre in Dallas, Texas, an embryonic forerunner of the design at Brown. There, like at Brown, the architects pursue a set of “limited but exceptional presets” that represent specific flexible arrangements that can give the various users “real flexibility in universal space,” according to Ramus. Ramus lamented, “you see time again, in all different kinds of typologies, buildings that can supposedly transform into anything and therefore, never do anything.” The inverse is true for REX’s works. According to Ramus, while the Wyly was designed with three preset configurations, the venue was able to put on 28 performances using 25 different arrangements for the space within the first year. Ramus added, “It’s proof that providing exceptional presets strangely leads to greater ease of experimentation and differential use than if you provide a black box that supposedly can do anything.”

For the PAC at Brown, the design team developed a series of metrics to help conceptualize and design the transformation process for each performance space. These calculations take into account not only how long each automated transformation will take, but also account for the number of human work hours required to complete each transformation. The analysis helps not only to tailor the design to what is easy and possible for the workers who will be responsible for reprogramming, but also helps the client put a dollar amount to each change. This complicated and multifaceted effort was combined with extensive scheduling discussions with the different groups that will eventually use the space, a series of collaborations that ultimately convinced the client that REX’s venue would not only fill a physical and symbolic gap in the university’s campus, but could also deliver the performance of five standalone buildings within the footprint—and budget, more or less—of one. According to Ramus, the client had two options: “Build four different venues, or a single venue that could, through automated and manual flexibility, transform among five potential configurations.”

In order to create a structure that can actually change its architectural configuration nimbly between various arrangements, the designers looked to fuse spatial and acoustic designs by creating a static, public-facing building shell that on the inside is serviced by stacked catwalks overlooking a central space where walls, floors, and ceiling change according to programming needs. In that central space, elements can shift to create flat-floored experimental media or concert hall-like auditorium spaces. With some changes, the venue transforms into a professional-quality recital hall with raked seating. A few more repositionings and an end-stage performance venue for dramaturgy can take shape. On the relatively few nights per month that the full orchestra performs, the venue's walls get blown out to their full extents, the floor raised, and the ceiling lifted to create a volume where “the orchestra [can] hear themselves and each other on the stage,” according to Carl Giegold of Threshold Acoustics.

“[Wyly Theatre] is proof that providing exceptional presets strangely leads to greater ease of experimentation and differential use than if you provide a black box that supposedly can do anything.”

The key reason this radical degree of reconfigurability is possible, according to Giegold, is because each of the performance venues is optimized by its own specific rectangular floor plan. With the maximum dimension for the PAC shaped by the largest venue, the concert hall, each of the other proportionally-specific performance spaces can be neatly tucked into the ensuing footprint. Giegold explained: “Overall, the diagram shapes the recital hall, once the basic geometry is right for those forms, much of the acoustic character follows along with it. The diagram went much if not most of the way toward generating excellent acoustics for all of the building modes.”

But don’t mistake the smooth line between this shape-shifting diagram and the building’s final schematic design to mean that the architects’ work is done. Far from it. Like any deceptively simple conceptual diagram, the scheme it eventually generates creates a multitude of design issues further on down the line. In this case, a key challenge for the project designers and consultants revolves around unifying the physical requirements for each transformation, including the necessity for material lightness and ease of mechanical movement, with the performance-based acoustical requirements of each performance space.

Whereas light materials are often thin and flexible ones usually supple, sound-focused spaces require rigid surfaces that are not only hard enough to reflect the sharp notes of a violin, but also thick enough to add warmth to the low-frequency glow that emanates from a bassoon, for example. In particular, classical concert halls, the types of spaces most professional orchestras are used to playing in, are often 100 or more years old, and are built from archaic construction methods that include stacked masonry walls and heavy plaster finishes that would be impossible to reconfigure if redeployed in a contemporary context. To combat these physical limitations, the designers turned to hybrid material elements, including stressed fabric panels, honeycomb fiber and plywood assemblies, and MDF-wrapped modules to articulate rigid-but-light repositionable elements for each performance space.

Giegold explained: “Overall, the diagram shapes the recital hall, once the basic geometry is right for those forms, much of the acoustic character follows along with it. The diagram went much if not most of the way toward generating excellent acoustics for all of the building modes.”

Surprisingly, glass is used as a finish material in certain areas, as well. Conventionally speaking, glass is a horrible material for concert spaces because it reflects sound without partially absorbing it, creating cold, hard noise instead of warm, enveloping music. At PAC, however, REX has designed substantial glass walls along the clerestory space that slices through the building in such a way that the glass’s mass and absorptive abilities mimic those of traditional masonry walls. So, while conventional concert halls might come with three-foot-thick brick walls, PAC will deliver an identical sound experience with two-inch-thick glass, instead.

“Identical” is not an exaggeration, either. That’s because in helping design the project, the sound consultants turned to 3-D virtual reality acoustic renderings as a way of testing and fine-tuning the space’s acoustical performance. To test the different materials and configurations, Giegold also created sound models for known performance spaces to peg the performance characteristics of the proposed PAC venues against real-world venues. Using technology that allows performers to listen from the vantage point of specific seats in each of the mapped concert halls, the designers are able to create acoustical renderings that respond in real time and reflect real-world conditions.

While the concert and performance spaces understandably consume a great deal of design energy in the project, the building’s relatively simple layout is also optimized for performance and multi-faceted use.

The architects designed a glass clerestory that slices through the project in order to fulfill the client’s desire that “the campus invade the auditorium and conversely to have what was happening on stage literally bleed out into the surrounding campus,” according to Ramus. As a result, the east side of the complex is extended 35 feet beyond the main volume of the building in order to create a public lobby that cascades via a stepped amphitheater into the sloped campus green below the structure. On the opposing side of the clerestory level, a more modest 14-foot extension serves to create an offstage space where performers can aggregate and warm up before the show. The two areas are linked by an eight-foot-wide promenade that wraps along the southern edge of the building and represents a literal manifestation of the university’s desire to use the building as an instrument for demystifying and expressing the artistic process from within.

Ramus explains that the approach, of uncovering beauty in the mechanics of performance, is carried through the project: “The building is a huge bridge, the combination of the clerestory and reconfigurability requires really serious structural gymnastics,” he explained, “The way that plays out, essentially everything moves and everything has to be lightweight at the same time everything has to look like it has a lot of mass.” Ramus added, “We made a bridge structure that is empirically super-heavy and acoustically super-light. That tension comes to bear on absolutely every part of the detailing of the building.”

Antonio is a Los Angeles-based writer, designer, and preservationist. He completed the M.Arch I and Master of Preservation Studies programs at Tulane University in 2014, and earned a Bachelor of Arts in Architecture from Washington University in St. Louis in 2010. Antonio has written extensively ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.