Callouts is a review series in praise of architecture, art, and the city.

Contrary to the common use of the modal verb “to call out” which emphasizes negative criticism, “Callouts” here draw from the architectural drawing tradition. Callouts in architecture establish a closer look towards a part of a project that requires more explanation and emphasized attention due to its complexity, uniqueness or typicality. They create a different, more detailed view of what has already been seen, expanding the reader’s understanding of the project.

Following that tradition, “Callouts” is a series of carefully selected complex, unique and banal projects, that have the potential to initiate a discussion, be didactic and affect their contemporary contextual mythology. Reviews for projects that do not satisfy these criteria can be found by typing “architecture” on your search bar.

Let’s start with something special for this first one now, shall we? This is a tale told in three parts. A tale about a building, a hill, and a monument.

First kiss

It was during the spring of 2013 right after finishing the 7th semester of my undergrad when I first found out that Renzo Piano was commissioned to design Greece’s National Library and Opera in one complex next to the Athenian coastline, under the sponsorship of the Stavros Niarchos Foundation. That information came together with an invitation to compete in a student competition organized by the foundation for the design of the project’s visitor center whose goal was to build buzz and interest around the site throughout the complex’s construction phase. What is more surprising was that the prize was 19.000 Euros and the realization of the winning project. Pretty good gig for a student right? Exactly my thoughts at the time when a couple of friends and I decided to participate. However, this is not a story on winning but rather that of an early flirt, a first kiss with what would become Greece’s most ambitious project since Zappeion if I am being modest, the Acropolis itself if I am not.

The Building the Hill and the Monument

The diagram of the project is quite simple. Lift and tuck under. Renzo Piano performs here masterfully the all-time favorite move of an architecture student with landscape sensibilities. Two lines form a low degree angle. A horizontal and a diagonal. The space between the two lines tells a tale of a building. The one above the diagonal that of a landscape. However, there is a third one, a line floating above the the other two telling a story in itself. The three tales could be told autonomously or simultaneously, but I would instead tell them in sequence, starting from the horizontal.

Building

The building first reveals itself through what is Renzo Piano has called the Agora, a rectangular open space framed by the new National Library, towards the north, and the National Opera, towards the south. The Agora both reveals the two institutions and serves as formal civic space for gathering, that connects them to the public space network of the master plan. Renzo’s Agora is perceived as the stage for public activity, serving the double role of the Opera’s gala and the Library’s plaza (as required by any self-respecting institution), satisfying at least the public part of its referencial name. Contrary to the gestural elegance of the stage of our imaginary play the set is nothing but underwhelming. A glass facade, reminiscent of Seagram building imitations, is cladding the enfilade created by the Agora. Of course, the system is more sophisticated than one anticipates, with automated external shading (solving for a problem the facade’s materiality creates for itself), and beautiful detailing of the mullion articulation that frames some of the clearest glass I have ever seen in person.

“Lifting” the curtain wall reveals the dualism of the program beyond the Agora. I was lucky enough to be part of one of the first tours of newly completed SNFCC back in January of 2017. The tour’s goal was to familiarize Athenians and visitors with both figure and ground of the master plan, giving a unique chance to wander both in the formal normally accessible spaces of the Opera and Library as well as their backstage, figuratively and literally.

The central axis of the H-Shaped plan serves as the cafe-restaurant, gift shop and a strangely glorified corridor leading to the complex’ parking, breaking away from any and all architectural tropes of classical axiality.

Let's turn left. The space feels tight. Like entering an Arizonian canyon, we enter the lobby of the National Opera of Greece, an eight-story high and about forty feet wide space that distributes the guests to their seats before the show under the guidance of floating Susumu Shingu colorful sculptures. The canyon conceals the Opera’s main performance space, a smaller alternative auditorium as well as a school of dance.

Entering the massive 301,000 sq. ft. space of the Opera House, one is struck by a captivating crimson-orange and purple hue that mystifies the atmosphere before the show. The house is filled with 800 crimson chairs weaving a red carpet in front of the stage, the balcony railings are clad with what seems to be cherry panels, the auditorium’s backdrop encloses the space in dark redwood, and the ceiling’s curves are contoured by violet LEDs creating a captivating gradient of materiality and light.

Right next to the main auditorium, the alternative stands as a generic implementation of a standard, vertical, wooden, red seating filled, boxy amphitheater as we have come to know it from other RPBW projects like the Isabella Gardner Museum in Boston. Nothing more to see here. Moving on.

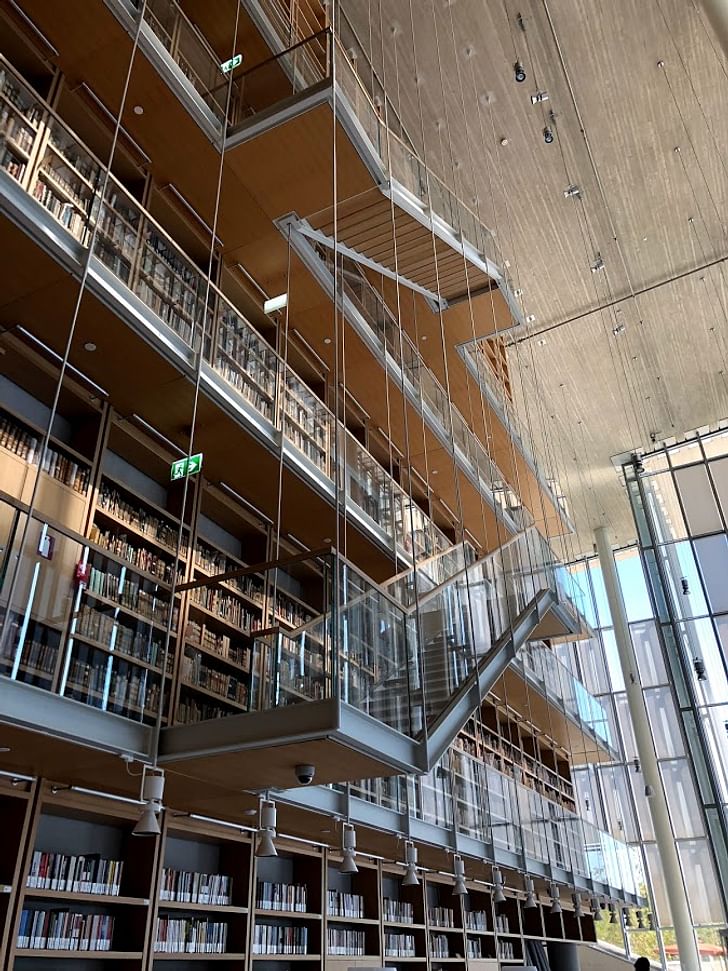

Mirrored on the other end of the Agora resides the National Library of Greece. Entering the library the canyon like lobby is repeated as a trope. However the L shaped space this time is filled with rare books and skywalks from top to bottom. The five-story wall made out of books accentuates the buildings mythology as a temple for learning. The rare artifacts of documented knowledge are openly presented to the visitor announcing the purpose of the building, while mystically drawing them to enter the library as no connection to them is apparent. Beyond the wall of books, the rest of the building is organized around an atrium and three lightwells.

A grand but uninspiring atrium, filled with out of place playful furniture, handles the vertical circulation and three-dimensional lobby of the library, while the three lightwells bundle up to illuminate the research and reading room at the cavernous north end of the building, emulating a mystical garden of silence within the busy complex.

There is a constant duplicity present throughout the building. Incredible detailing, underwhelming architecture. Excellent materials, finishes, detailing and performance, form spaces that try to but never really reach an inspiring level of spatial poetry. The Opera’s and Library’s pragmatic programmatic nature battles their metaphysical aspirations. In fact, I will go as far as saying that the building’s excellence in execution and precision, comes as a boring architectonic statement. If your goal is to see radical architecture and you have visited any RPBW building made within the last 10 years, the SNFCC will provide you with no drama.

Hill

Going back out in the Agora and walking outwards towards the east, one is greeted by the Canal, a long, linear body of water that dominates the north-south axis of the master plan, creating the illusion that the nearby Aegean shore is extending into the site, figuratively connecting the Athenian mainland to its waterfront. The canal naturally directed me northwards. Looking forward, the city. To my left, the second line, the diagonal formulating the hill of the Stavros Niarchos Park as it is formally known, in all its concrete retaining wall glory. The northernmost end of the canal is marked by the visitor’s center, a Farnsworth house designed by Renzo Piano, or a typical well-designed canopy pavilion, either one. Close your eyes, imagine how that would look like. You’re probably right. This is the intersection of the two main lines of the project, where building meets landscape.

At the foot of the hill, the city ends abruptly. The ground turns from concrete to bare earth and the surroundings transform from densely built “polykatoikias” to lush combinations of dark and light green, turquoise, brown, yellow, purple and blue. The air is filled with a wide palette of aromas that only allude to one thing: greek topos. The story is not as poetic if we look at the hill’s plan. Here a combination of an enlightened French garden planning with notes of Anglo-Saxon park design drawn by an Italian architect, organize the landscape into discrete areas of programming.

The Labyrinth, the Sound Garden, the Mediterranean Garden, the Western and Southern Walks create the hill’s mythology, all surrounding the main event space called the Great Lawn (wink-wink) where big outdoor events can take place. However the story told by the hill is not French, English or Italian but highly Hellenic. It only becomes cohesive only through the rough elegance of the greek landscape, stitching together referential words that allude to a certain content into a beautiful difficult whole.

The hill’s story can really only be told through the point of view of a “flaneur” taking the path towards its zenith. Ascending the landscape, one is cornered with aromatic plants and shrubs, oregano, thyme, lavender, rosemary, and salvia, that engage touch, smell, and sound actively or passively.

Vistas are directed by grandiose olive trees and their silver-green leaves dancing to the wind’s baton, positioned along earthy paths across the topography. After walking for a few minutes, the slight inclination has lifted the perceivable horizon to extend across the city of Athens rising slowly above the city’s built mass, reorienting the flaneur within the topos.

Continuing up the hill, the vegetation becomes more scarce, arriving at the serene scenery of a golden hay field. The loud silence of hay in the wind seems to stop time, making one look around one last time before that last line of the project, the one above and beyond the golden field.

Monument

Look ahead. It’s the thing you have been staring at all along. That thing at the top of the hill. And now here you are in front of it, looking in awe through the frame created by the golden field of hay and the sky. It is not a thing though but a composition. Columns that support a roof and an enclosed space placed on a pedestal. You have seen this composition before though, haven’t you? Yes on another hill maybe or maybe not. You are in front of what RPBW calls the Lighthouse, but I am going to argue something quite a bit different.

The Lighthouse is located on the top of the hill of the Stavros Niarchos Park, directly above the Greek National Opera and Library. In most scenarios, the composition of a columnated space on top of a hill that stands out in the city’s skyline would potentially have one particular reference. In the case of the SNFCC’s third and final line of its diagram, that composition is located in Athens, making the potentiality of that reference more of a certainty. Here there is another columnated structure on top of a prominent hill. Yes, the one that is slapped on the main facade of mostly all neoclassical architecture.

The Parthenon.

The comparison here is unavoidable. In fact when one arrives at the top of the Hill and looks directly north, there it is, on top of the Acropolis right across the skyline. Renzo Piano has created his temple upon the hill, a monument that refers to the monument of Athena. Could the complex function without it? Absolutely. Would it have the same significance or iconography? Absolutely not.

Understanding the project within its broader context, it is perceived as a colorful elevated landscape within the Athenian concrete jungle and right at the top, a simple canopy supported by slender columns. A lone object of desire. A destination. However, Renzo’s Parthenon is a very different type of monument. It is not one to worship from the outside, but one that requires its experience from within.

At the end of the hill, the canopy stands as a lonely shadow at the end of the sun-filled climb. Entering the space underneath it, the vision clears up. The harsh sun stops obscuring the view of the landscape. The Lighthouse becomes the last stop of the journey. The supporting columns, even though highly visible from the Agora and the Hill, almost disappear through their contrast with the Athenian blue sky.

At the end of the path under the canopy the horizon towards the south changes. No more buildings, hills or parks. Only the Aegean sea. The canopy becomes a panorama that captures everything unique about Athens locally and Greece at large. City, hills, landscape, and water all coexist in one unified composition. The Lighthouse, even though assuming the monumental tropes of the Parthenon on top of the Acropolis, becomes an autonomous monument. One that inverses its own exterior iconic perception. An architectural element that ties the stories of the building and the hill together into a complete trilogy. A monument to the Hellenic Topos.

Konstantinos Chatzaras is a New York based architect and writer, focused on the contemporary multiplicity of the architectural and urban form seen as a plural whole. Konstantinos holds his Master of Architecture degree with commendation from Harvard University's Graduate School of Design ...

1 Comment

An insightful review!

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.