Looking to the future, Designing Practice is a series that explores how the practice of architecture can evolve in the 21st century. Framed by contemporary conditions, the series asks architects and designers to consider the discipline’s broader context and imagine new models for moving architecture forward.

In this installment, we talk with architect Lola Sheppard, partner at Lateral Office, and her approach to the discipline as it reaches across multiple scales, thinking through temporal, social and territorial implications of a project.

Lateral Office was founded as an experimental design practice. Can you tell us a little more about your work and why you started your practice?

We started the practice in 2003, upon our return to North America, after two years of working in London. Although we each came with somewhat different approaches, we both knew we were interested in questions of public realm, and it in the intersection of architecture, urbanism and landscape.

We received a teaching fellowship at Ohio State University’s Knowlton School of Architecture which offered us a unique space in which to speculate, test working methodologies, and develop the idea of design research. We realized we were drawn to spatial conditions typically overlooked by architects—attracted to sites which eluded conventional responses. This began with our Flatspace research (2003-04) which looked at exurban retail corridors, and this predilection has continued ever since.

For an office that brazenly confronts today, you’re critically reimagining contemporary conditions across the built environment. How does speculation play a role in your design process?

Lateral Office has consciously embraced a practice which operates laterally –teaching, writing, editing, designing, curating (publications, exhibitions, and conferences). Each of these methods and practices are vehicles for design thinking, and for questioning and repositioning the role of architecture within our physical and cultural environment. Part of this repositioning involves destabilizing many of the givens within which architecture has traditionally operated. Speculation allows us to ask how architecture could operate differently, how the environments which we occupy on a daily basis might be different. Research enables us to understand of how they came to be in the present condition, and design enables us to speculate on alternative futures.

Speculation allows us to ask how architecture could operate differently, how the environments which we occupy on a daily basis might be different.

As both an architect and educator, what do you see as a major focus of contemporary design education? How best should we prepare future architects for changes in practice?

We have long advocated for architects to come into the design process earlier. Typically architects are brought in once the site, program, budget, and the users are established. But we have tremendous abilities to think synthetically, across disciplines—from the social, the economic, and the political, to the formal and technological—and these skills are often under-valued.

When you look up architect in The Webster dictionary, the following definitions are listed:: (1) a person who designs buildings and in many cases also supervises their construction, (2) a person who is responsible for inventing or realizing a particular idea or project. However, it includes ‘related words’: builder, maker, producer; captain, commander, director, handler, leader, manager, quarterback; contriver, designer, formulator, originator, spawner; arranger, hatcher, organizer, planner, plotter, schemer; finagler, machinator, maneuverer; developer, generator, inaugurator, initiator, inspirer, instituter, pioneer.

I love this list. In Beyond Patronage, (Edited by Joyce Hwang, Actar 2016) I argued that these ‘related’ and rarely considered words seem far more productive in defining a possible ambition for the profession today. They suggest an anticipatory role, one that is strategic and opportunistic. It repositions the profession from one that ‘invents’ buildings and spaces, to one who conceives of ideas, schemes, and relationships, of which buildings and structures are a part. In these scenarios, the outcomes are less clearly defined, yet perhaps more full of potential, and offer an alternative to the conventional view of the architect as ‘creator’ and ‘implementer.

By its nature, architecture is slow to change. Do you believe architects should attempt to maintain social and public relevance?

if architects don’t attempt to maintain social and public relevance, I’m not certain what we are doing...

Architecture may be slow to change from a technological and construction perspective but in terms of operative thinking about sites, stakeholders, design approaches, etc.., architecture can and should be at the forefront. To be honest, if architects don’t attempt to maintain social and public relevance, I’m not certain what we are doing – we risk being reduced to makers of fashion, which seems to be a loosing proposition, both intellectually and given how quickly fashion operates, and how slowly architecture moves.

To quote Buckminester Fuller: “architects, engineers and scientists are all what I call slave professions. They don’t go to work unless they have a patron... When you’re an architect, the patron tells you where he’s going to build, and just what he wants to do.” If . … The architect is really just a tasteful purchasing agent.”

In the United States, the American Institute of Architects recently created a Center for Practice that will, among other aims, “identify and advance areas of new business opportunities, new business models, new skills, and new markets” for architects. Amid increasingly automated design processes and narrowing project scopes, how do you see the agency of the architect evolving in the 21st century?

The agency of architecture is precisely to resist being merely “tasteful purchasing agents.” We need to engage complex and urgent contemporary problems. So the question is what is the disciplinary field in which we should operate today? And what are the tools and modes to operate within this field?

While we have strong interests in questions of ecology, landscape, even anthropology, we see ourselves distinctly as architects. We have begun to embrace the possibility of the “undisciplined” practice. This practice is not anti-disciplinary, nor necessarily multi-disciplinary. Instead, questions may be provoked outside of the discipline, although the methods of response remain within the discipline. Looking outside of the discipline is not to avoid its particularities, but rather to expand and clarify the questions, and ultimately the agency, that it can have. But immediately a dilemma surfaces of how an architect should operate within an un-discipline? We’ve gotten increasingly interested in this idea of detective work as a productive model for alternative practice and research, one who uncovers overlooked spatial phenomena, decodes the forces at work, and then envisions design responses, alternate scenarios,

From naming a practice to the type of projects an office takes on, architects must often consider legacy. What do you hope is the legacy of Lateral Office and your work?

Much of our work over the past decade looks at rural and remote sites, where the challenges of architecture engage profound questions of climate, environment, geography and unique cultural contexts. Through our work on the North and our recent book Many Norths: Spatial Practice in a Polar Territory, we got very interested in the idea of spatial practice as an expanded way to understand ideas of vernacular that move beyond form and tectonics, to much broader understandings of social and cultural practices. These practices that may have permanent or impermanent imprints on the land, bur regardless, might shape how we conceive of architecture in these contexts.

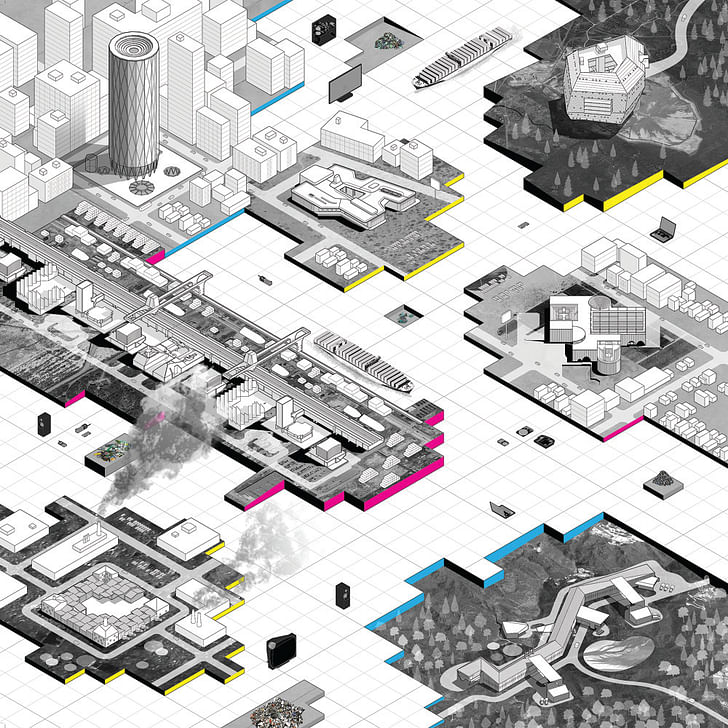

We like to think about architecture operating across multiple scales, thinking through temporal, social and territorial implications of a project. These questions transcend any given site—one might ask this of North American suburbia, rural Africa or the circumpolar regions. I suppose we hope that the legacy of Lateral Office will have been to open up news questions and territories of research for architecture, to expand the tools of representation and documentation that architects might use to engage such questions.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.