The past decade has witnessed the canonization of a new type of architectural publication, the anti-monograph. This type of book could be defined as an early retrospective publication of a working architect on the architectural avant-garde. Unlike the traditional monograph which collects and focuses on a discreet body of work from a period of time, these books prefer to collect and frame the process and thought that animate the firm’s approach, often through speculative and projective work.

Speaking to David Benjamin of The Living at a GSAPP event “Making Books Now” in September 2017 (in advance of the publication of this book) Benjamin Aranda said, “The making of a book—like the making of a building—imposes a striking finality, or decisions that one needs to commit to. I think that’s why architects love making books, because it’s almost a kind of rehearsal.”

Architects of course, have always done this. From Le Corbusier’s Vers une architecture to Vitruvius’ Ten Books (in which Vitruvius, disappointingly, includes drawings but no photographs of built work) architects have always rehearsed for projects and sharpened their ideas in advance of building. The current crop of these titles owe an obvious debt to Reiser + Umemoto’s 2006 Atlas of Novel Tectonics. Coming before our current moment of second (third?) wave postmodernism, it was the synthesis of many of the preoccupations of the prevailing avant garde design agenda. It describes a body of work not so much as a collection of discrete projects, but rather as a set of procedural solutions, effects, questions and processes that when confronted with specific building sites, functional or formal problems gave rise (or could give rise) to specific solutions - the projects.

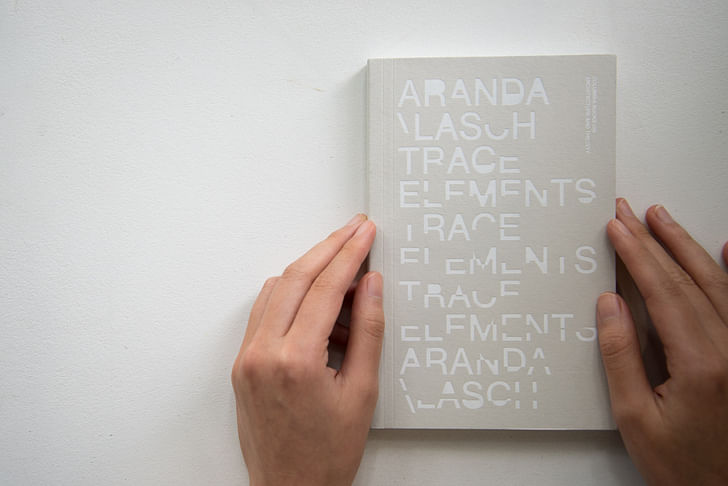

HHbR, WORKac, Tatiana Bilbao (forthcoming), and many more have released titles in this vein, but how do we distinguish if the content contained within them—or even the format itself—contributes meaningfully to the profession and practice of architecture? Is the explication and exultation of process sufficient to make an entire publication from, especially now in our over-saturated architecture media world, and especially if the work is not built? Aranda\Lasch, of course, are not mere paper architects (though 12 years later, neither anymore are Reiser + Umemoto) and beyond helping young firms find work, these publications do have an aggregate benefit. To practice is one thing, but to write about the ideas, motivations, and processes behind practice, is to distill these to their essential. To then present them to the world is one of the most potent forms of discourse architects can engage in, and even more compelling when accompanied by built work.

Trace Elements does not present an easily digestible theory or treatise on architecture. Rather, like much of its content, the publication builds a soft manifesto

Trace Elements does not present an easily digestible theory or treatise on architecture. Rather, like much of its content, the publication builds a soft manifesto out of fragmentary vignettes, traces of process, thought and materials. A cohesive picture of Aranda\Lasch only emerges once the reader well and truly understands the process and inspiration, with each of the 5 chapters of the book building on the others. The reader is reminded again and again through varying lenses (matter, drawings, physics, history, and craft) that complexity resides in the part, not the whole. Yet, there is something in Aranda\Lasch’s ability to assemble complex parts into an emergent whole that is evident in the work as much as it is in this publication.

Aranda\Lasch’s success in assembling this title to convey their values and inspiration in an utterly unpretentious and accessible manner is a testament to their roots as a process-based practice. Praise aside, this title may prove somewhat opaque to those not more familiar with their ouvre, however it should inspire further exploration. Reviewing Aranda\Lasch’s early publication of Pamphlet Architecture 27: Tooling or experimental early built works such as Camouflage View reveals the essential procedural and thematic elements in the work. This type of publication is perfectly suited for capturing the essence of their work (or maybe vice-versa) and is itself a procedural work. The conversation Benjamin Aranda and Chris Lasch have been having since finding their feet after graduating from Columbia nearly 20 years ago has been about capturing the mystical and ephemeral qualities of architecture in a procedural way. That they would employ the same rigorous logic to print should come as no surprise to those familiar with their work, and should spur the unfamiliar to educate themselves post-haste.

Trace Elements is divided into five chapters. The first, “Organization and Ruin” seeks to position AL’s work within two contextual frameworks: that of matter— the physical— and that of architectural history and pedagogy—the theoretical. They are far from the first to reference the rupture in architectural thinking at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, but the lens through which they frame the historical—pairing it with matter and its bearing on the organization of our world—demands the reader re-appraise our ideas about history while also considering how the idea of ruin fits into contemporary practice. The historic parable of ruin and rebuilding and the philosophical baggage associated parallels that of the destruction and reorganization of matter—elemental to the making of buildings.

Drawings are presented in “Broken Drawings” as generative but also representational, a bridge, a dead end, an animating force. The text here brings to mind echoes of Constance, McLuhan, and Piranesi for whom drawing was an act into itself—generative, charged, partisan. Aranda\Lasch develop form and organizational ideas through drawings that become object and environment. In both Railing Series and Night Drawing and The Morning Line, Aranda\Lasch forcefully illustrate the animate and emergent powers of drawing as an integral part of developing projects, and as a practice to be pursued in and of itself. You never know where a drawing will lead.

Aranda\Lasch highlight important milestones, traversing the work of mathematicians, physicists and historians to identify the cases that define these instances of emergent geometry

Like much of the preceding book, “Quasicrystals” proceeds in the best tradition of this new style of publication. Aranda\Lasch highlight important milestones, traversing the work of mathematicians, physicists and historians to identify the moments and cases that define and describe these instances of emergent geometry. Their work, whether at the scale of building or object d’art, makes it clear that they not only understand these phenomenal geometries, but are able to apply them to practice. The explanations and illustrations pairing theory and history with built work illuminate the intellectual and experiential leap that Aranda\Lasch make from abstract scientific subject matter to a forceful organizational and compelling aesthetic parti.

The chapter “History is Generative” carries with it echoes of the quasicrystal obsession (itself a historical journey for Aranda\Lasch) but frames these historic and contextual narratives in terms of specific projects. Through this frame the reader can understand the irregular path from matter to drawing, and history to the intellectual and theoretical constructs and narratives that Aranda\Lasch work from. Whether diving into the history of snow crystals, creating a dialogue between constructed agricultural landscapes and built form, or interrogating regional vernacular, Aranda\Lasch’s generative approach to projects yields results which are not only intellectually rigorous (the seemingly easy part for younger practices) but functionally performative, aesthetically compelling, and well crafted.

The last chapter, “Baskets and Architecture” is primarily about craft and community. Aranda\Lasch use the basket as a metaphor for the organizational and physical processes of constructing a building, of constructing a consensus in a community that precedes any building. This metaphor might be obtuse had Aranda\Lasch not spent years collaborating with basket weavers such as Terrol Dew Johnson of the Tohono O’odham tribe to explore the algorithmic and generative processes that go into traditional weaving and handcrafts but exist below the radar in our obsessively quantifying society. Craft is where the elements described in chapters preceding this last are integrated into a cohesive whole, just as a basket is woven together from many disparate threads. For Aranda\Lasch, the material and pedagogical challenges of working with matter, the representational and generative possibilities of drawing, the intellectual and organizational properties of the quasicrystal, and dialogue with context and history are all interwoven in this final anti-polemic.

In their own words, “In a craft like weaving, ritual and material action are always intertwined… the weaver reiterates the foundational meanings of society. Its place in the natural world… exists in an extended process of materialization. Architecture as a material practice is similarly intertwined. Embedded with larger collective structures - structures that are rebuilt and revitalized over and over again. In Architecture and in weaving… the process is more about the relationship around the object than the object itself.”

Nicholas Cecchi is an architect born in Denver and educated in New Orleans. Following completion of his degree, he worked briefly in single-family residential architecture before leading the design department of a Denver-based boutique architectural and sculptural design and fabrication studio for ...

1 Comment

On order. Thanks for this review.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.