The VeloCity team met through PedElle, a charity cycling endurance event open to female riders working in the property industry. Each successful in their own right, they decided they wanted to work together combining their expertise in architecture, design, engineering and town planning - a place-making competition developing the corridor that spans Cambridge, Milton Keynes, Northampton and Oxford, seemed the perfect opportunity.

I recently met with the team to find out more about how they work together collaboratively and what made their entry stand out. Since we met they have gone on to win the 'The Cambridge to Oxford Connection: Ideas Competition', cementing their exciting future working together.

How many people are in the team and what are your backgrounds? How did you come together?

6 in total; Sarah Featherstone, Director of architecture practice Featherstone Young, Kay Hughes, Director of architecture practice Khaa, Annalie Riches Director of architecture practice Mikhail Riches, Petra Marko Director Marko and Placemakers , Jennifer Ross Director at Tibbalds, a town planner by training, and Judith Sykes Director at Expedition Engineering who is part of the infrastructure and masterplanning team.

The competition called for a multidisciplinary team but was it the competition that instigated this collaboration or was it something you had considered before?

Annalie: My practice does a lot of competitions and so I am always looking out for competitions. I remember Jennifer (Ross) did a competition and I was really jealous I wasn't working on it with her because she had such a brilliant idea. Consequently, I was looking out for one that had an architecture and planning crossover to try and get into work with her.

When The Cambridge to Oxford Connection: Ideas Competition came through I sent her the brief and she said why not! We were discussing creating a team and utilizing the network of people we met of our annual cycling trip, PedElle.

Petra: PedElle was set up by Jennifer Ross and Claire Treanor as a reaction to the MIPIM ride which is very male-focused and an extremely long distance over five days. They wanted to get more women into cycling but also create a similar networking opportunity for women in the industry. It was the perfect way to find a team together.

Sarah: The comradery that happens on these trips, we are often cycling up very steep hills and really have to motivate each other, encourages you to want to do something together. Annalie and I had previously done a couple of competitions as a consequence. That sense of collaboration, we are all quite interested in any way and when you make those kinds of bonds it's just nice to try and continue that on.

When we walked into the competition briefing session it was all male teams and we felt very aware of the fact we were all women. But mostly I think it was just because of PedElle and the connections we had made there that we wanted to work together on this project.

Annalie: We also just really wanted to do something around cycling.

Could you tell us more about the project and how you worked together designing your entry? What made your entry stand out?

Sarah: It began with a Bucks Fizz over breakfast! We wanted it to be fun! Cycling was very hardcore and we never really had time to sit down and enjoy each others company and have a nice meal.

Petra: At breakfast we discussed our ideas, then everyone went off on holiday.

Annalie: We always wanted to focus on cycling and the opportunity this high-speed infrastructure would give to a smaller scale of travel. Jennifer pointed out we needed to tackle villages, which is not what anyone else would have thought of I think and is not the obvious thing to do.

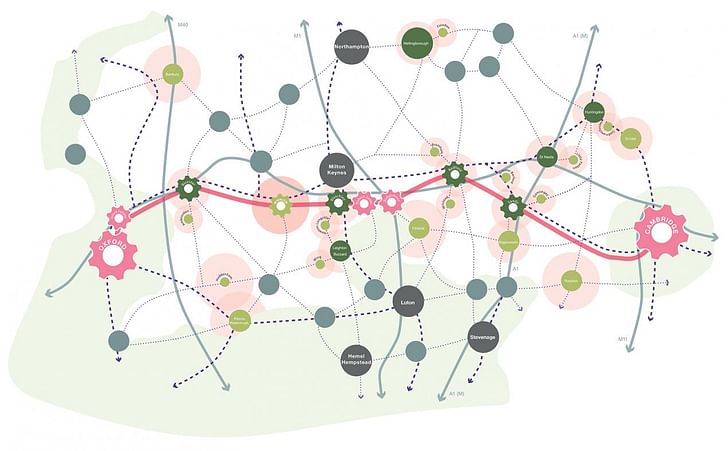

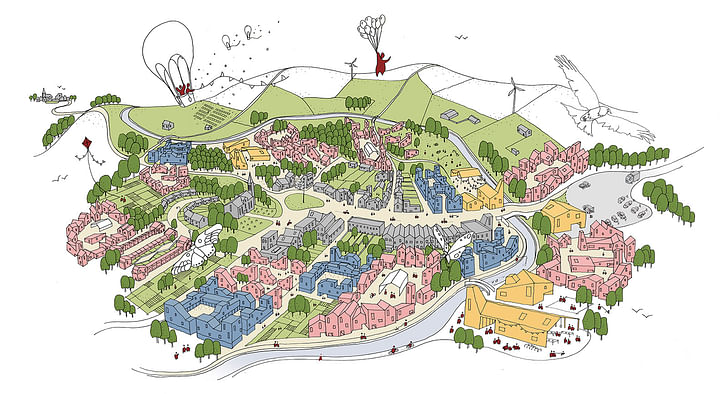

Sarah: The majority of the settlements between Oxford and Cambridge are villages - only one or two miles apart and they were going to have this very fast road link that would make them all connected. We were looking to the future and how we could reduce cars and therefore what were the other ways of connecting these villages. We wanted to play the fast against the slow really. Re-invigorating theses villages, which at the moment are of a very particular demographic and not for everyone. The whole competition was about placemaking, how do you link infrastructure with placemaking and I suppose the thing about villages is they already have a strong character and identity as well as a sense of place - we could build on that.

Petra: Also, we wanted to point out that perhaps these villages are losing that sense of place because there is an aging population and they are isolated with no pavements, no shops, loss of schools, village greens.

Judith: It’s not that people don’t want to live there, it's just not affordable - so how do you create affordable communities that will attract a great mix within a community including entrepreneurs that they want to attract to that corridor.

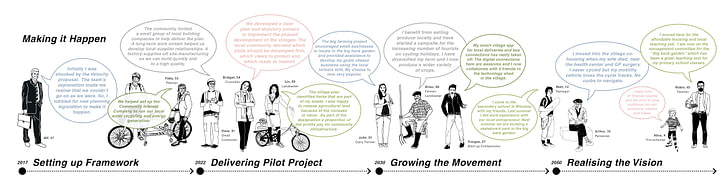

Sarah: We had to tackle and keep the sense of place because at the moment they are building houses - maybe 15 a year in a very ad-hoc way. Looking to the future in 30 years, there will just be this suburban sprawl so we wanted to do something that was much more about keeping the core of that village and then building in a much higher density way in five or six fields immediately around the village - wrapping it round rather than sprawling it.

Judith: There is a natural tendency to try and fix this problem with a massive masterplan and a big stamp and politically I think that is very attractive. However what you find is less of these smaller scalable solutions because they are different in the way they are delivered. The downside to these big masterplans is they are actually very difficult to deliver in practice. What is unique about this scheme is that it is inherently deliverable because it is lots of small-scale developments that can be easily delivered with the support of the community.

Sarah: Immediately we were looking at existing road networks, several of which we realized could be given over to cycle routes without having to create a specific new path. It wouldn't actually stop vehicles coming in to deliver or connect back to the big towns clustered around.

Petra: We were told halfway through that we were the only team looking at villages and we were a little worried however we knew we were being brave and tackling the biggest problem. It’s far easier to allocate brownfield land around cities and we are not saying that that shouldn't be, but nobody wanted to say that this beautiful village field will be developed and I think that our proposal really looks at that problem.

Annalie: It is not just a problem for this corridor; it is a problem throughout the UK that villages are either second homes or populated by an aging demographic. They have lost a lot of their facilities that make them viable places to move to.

Judith: There is also a health and well-being component to this as well, if you are trying to attract families in places where they can live a healthier, more active lifestyle, providing alternatives to dense urban developments that can really stimulate activity and better food production and healthy lifestyles are important.

Annalie: You think these villages are really far apart but actually they are only, in most cases, a mile apart. But you would never walk because there are no pathways, just an A-road so they feel very disconnected. Whereas actually with a little effort you can connect these place.

Sarah: At the moment there is no reason to go to these neighboring villages, people just go to that largest town nearby to get what they need. The scheme was a lot about bringing these villages back together and making them able to support each other. So they can travel across what we called 'the big back garden'.

It is not about stopping people driving but rather making it much easier and safer for them to cycle and walk.

Judith: We can see this working in other cities, like Copenhagen for example, where they have invested heavily in their cycling infrastructure.

Do you think multidisciplinary studios and collaborations are a more effective way to create?

Judith: The company I work for is already multi-disciplinary across architecture, communications, design, and engineering and I think you find that’s the case in a lot of engineering practices but the bit I find most interesting is the interdisciplinary work. That has worked particularly well in this team - you come to the table with your particular skills and expertise but you don’t allow it to put you in a particular box, it is a collaboration. It’s been an incredibly supportive and collaborative environment to work in, which you don’t necessarily get in traditional design team hierarchy.

Petra: At the start, we didn’t really discuss any roles, and consequently it grew very organically and we each developed a particular aspect we were interested in while discussing the overall vision together.

What hurdles have you come across working on this project and working together as a team?

Annalie: Organising all the back and forth between six people and the endless emailing!

Sarah: We are all directors of our own companies and pretty busy which makes it difficult to organize and plan such a thing in five weeks.

Do you plan to work together again as a team?

Sarah: I think now is the time for us to re-group, review what we’ve done and where we want to take this. We all feel this has been an amazing process and very positive and actually it has worked very well.

This project could be applied across the UK and outside of the UK too, that is something to consider and how we can keep that energy going and how we manage future projects.

Judith: This competition and the organizers have been particularly good at drawing out work from smaller practices, not just the usual larger names, and it has shown how we can put design at the forefront and how architects really can contribute to these conversations at the highest level. It has also made it clear that currently infrastructure happens in isolation with a very defined red-line boundary and that approach isn’t going to deliver the growth we need.

Ellen Hancock studied Fine Art and History of Art at The University of Leeds and Sculpture at Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University in Istanbul.Now based in London she has a keen interest in travel, literature, interactive art and social architecture.

2 Comments

Annalie: You think these villages are really far apart but actually they are only, in most cases, a mile apart. But you would never walk because there are no pathways, just an A-road so they feel very disconnected. Whereas actually with a little effort you can connect these place.

This is SO applicable to US suburbs! They're walled off from one another to the point that the only way to get from one kid's house to her best friend's house 500 yards away as the crow flies is to get in a car and drive 2 miles.

I love small interventions across a huge swath. It's exactly the opposite of Ville Radieuse. The massive changes at urban scale of this century should be happening in tiny, personal increments.

Well done.......I will step right out and purchase a "Bromy". I am concerned that over time, EbHow et all, new towns, and urbanized suburbia concepts all have great measure failed. Here in the US, the trick seems to be "controlling the money": developers seek income and profit being the largest risk takers, the jurisdictions seeks and requires tax revenue to keep the show on the road. Does one hand feed the other?

Lewy

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.