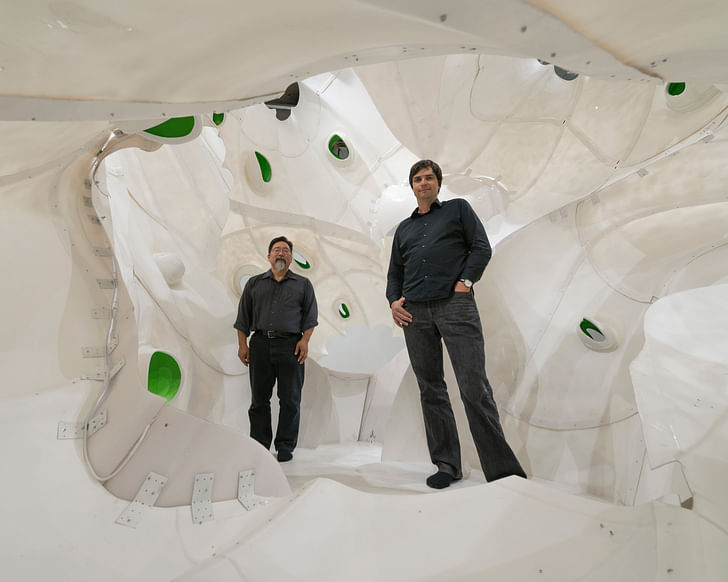

Baumgartner + Uriu (BplusU) are innovators known for pushing boundaries. With an in-house fabrication studio, the LA-based practice is consistently experimenting with the latest digital techniques and materials. Founded in 2006, the firm is led by Herwig Baumgartner and Scott Uriu, both with a background in music and working for Frank Gehry. For this week's Small Studio Snapshot, we talked with the duo about how they got their start, what drives their work today, and what is on the horizon.

How many people are in your practice?

Anywhere between 5-15.

Why were you originally motivated to start your own practice?

Starting our own practice was a plan that arose almost immediately after completing school. For us, the question wasn’t if we wanted to start our own studio, just when. Ultimately, we decided it was best to take an opportunity to get some experience under our belts before jumping off. For the next several years, we worked for Gehry, Coop Himmelblau, and artist, Richard Serra; all of which proved to be valuable experiences on many levels. When we opened our office, however, we knew it would be important to ‘unlearn’ some of that experience. We needed to set up our own process and method of running things; it was a crucial mechanism of the practice that couldn’t be learned, but needed to be developed.

What hurdles have you come across?

The challenges in the beginning were plenty. What kind of a studio do you want to have? What kind of work do you want to do and won’t do? How to get clients, run a business, develop your design agenda, etc. Addressing these questions and then adapting our methods to refine our answers, is exciting, but continues to be challenging. The practice is a constant evolution. We have been around for 12 years now and continue to adjust and refine our business model. Architecture is a marathon and not a sprint, so you need to be able to enjoy the ride and the work you do. If not, then change it and make it new.

Architecture is a marathon and not a sprint, so you need to be able to enjoy the ride and the work you do

How did the office start and what were the first 2 years like?

We started in a garage in Venice moonlighting and doing tons of competitions and all-nighter’s. It was a lot of fun, but also brutal in terms of energy and hours that went into it. Eventually we moved into a real office space and quit our day jobs. The first two years were mostly about developing ideas and a way of working that was our own. We had to purge many things that we had learned from other offices, and then re-learn them. In the end we didn’t leave a stone unturned and questioned everything we had taken for granted before. Scott and I still do this today, when we are developing ideas; they are heavily vetted, dissected, argued for and against. Make your case and then defend it- if you can’t the other might have a point. It’s a constant dance, that’s how Baumgartner+Uriu was founded.

How do you find yourself splitting time between your various pursuits in the field?

Many of our projects have developed out of intense explorations into a focused architectural agenda

It can be a challenge. Building a practice, developing your theory and design, all while getting work and clients, takes time and you can easily spread yourself to thin. That said, we have found it a necessity in our process to set aside time devoted to research. Many of our projects have developed out of intense explorations into a focused architectural agenda. For example, many of our installations and smaller scale work deal with thinness, where surface and structure collapse into a single element. This led to working with new materials and directly translated into the fiberglass composite house we are doing in the Hollywood hills. Developing new relationships with people, clients, and evaluating the architectural landscape to see where you can carve out a niche, is equally important. You have to be able to wear many hats.

What other mediums of implementation does your office pursue?

Besides doing exhibitions and installations, (which as mentioned, are important for the development of ideas in our office, and often a predecessor for larger scale architectural work) we enjoy working on furniture and product design. We have a pretty elaborate fabrication shop in our office, with lots of digital fabrication tools, scanners, 3d printers, a CNC machine, etc. We can do a lot of prototyping in-house. We like being able to work on things one to one, and refine ideas at a fast pace. It is easy to switch out materials and work iteratively on many porotypes simultaneously. We have been designing a range of products from 3D printed lamps, to an aluminum cast lounge chair, to carbon composite prosthetic limbs.

How do you balance theory and production in your office?

It’s a constant back and forth. Writing and lecturing are a platform for us to formulate our theory, flush things out and set new agendas in the office. We then carefully test these ideas on smaller scale work, competitions or exhibitions before deploying them into “real” projects. Apertures is a perfect example of that workflow, it started as a text, then materialized as a conceptual project for the Archilab exhibition in France. It later developed into an installation at the SCI-Arc gallery until finally becoming a design for a 10,000 sq ft private residence in the Hollywood hills. However, it is rare that a body of research comes together in a single project, generally because it requires a client that is all in and willing to go the distance.

What is 5 / 10 / 15 years down the road? Who knows?

Design and build as much meaningful Architecture as you can, and win the Pritzker.

How does academia make its way into your work?

Academia needs to be a place where the next generation can start finding themselves. That automatically implies a certain level of resistance on the student part

There is a symbiotic relationship between what you are developing with students at school and what you are doing in your practice, but they don’t need to necessarily align- in fact, we prefer if they don’t. We are not interested in teaching students how to make things exactly how we do, and while there are plenty of faculty who do that, it’s not our model. Academia needs to be a testing ground for ideas and a place where the next generation can start finding themselves. That automatically implies a certain level of resistance on the student part, which we wish there would be more of.

What project would you most like to be remembered for?

The one that we have yet to build.

Is scaling up a goal or would you like to maintain the size of your practice?

A firm grows with the projects it is willing to take on. Eventually we would like to grow our practice to 25- 50 people, that’s when it still feels like a studio and would be an ideal size for us. Anything bigger than that, and it becomes more bureaucratic than we want. However, the quality of the work you do is much more important than the size of office you want to have. I.M. Pei summed it up perfectly when speaking enthusiastically during an interview in regard to the genius of Louis Kahn: “...but what about you Mr. Pei?” the reporter asked “you also have built so many great projects,” I.M Pei paused and smiled then yelled at the reporter “its quality not quantity that matters.” I often think of that, how clear that was for him, it’s humbling. I think you need to continually ask yourself what kind of architect you think you are and what kind of architect you want to be, then make your decisions accordingly.

What is the Thesis of your office, your work and how has it changed?

We both came from a music background and initially worked on a thesis of relating sound to architectural space. We investigated this idea through various means including custom software that transformed sound into 3-dimensional form and new material technologies that allowed us to augment the familiarity in architecture and tease out the uncanny through interactive spaces. For us, the familiar and its relationship to the uncanny is a lens through which we can look at our work. How familiar is it? Or how uncanny is it? The uncanny for us opens the door to the unknown yet it has one foot in reality and one in fiction. It is this duality of multiple realities that is of interest to us and how to achieve this in Architecture. We find the work intriguing if it doesn’t completely reveal itself at first and remains not just mysterious but often strangely familiar.

What are the benefits of having your own practice? And staying small?

The ability to pursue your ideas and the freedom to shape the way you practice Architecture. You are responsible for your destiny so if you don’t like it, change it! Staying small is not necessarily an ambition of ours, but rather, a product of certain choices we have made over the past few years. We definitely want to grow beyond our current size, at the same time we want to stay in control of the process.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.