I walk past Acme's London office regularly and there is almost always a passerby staring into their window with a rather bemused, albeit intrigued, look on their face, not quite sure what to make of this golden cave of wonders. This is no accident, Friedrich Ludewig who founded the practice in 2007, told me on our latest Studio Visit. Having heard of a Japanese architect who shared his studio with his florist wife, Friedrich was inspired to create a similarly curious studio space with a speculative function to tantalize clients and the local community alike.

This playful and idiosyncratic approach is synonymous with Acme and can be seen in all of their projects, most recently the award winning Victoria Gate shopping mall in Leeds with its striking diagrid facade.

Having just celebrated their ten year anniversary we found out more about their journey so far and what the future holds for this exciting studio.

Location?

London - Old Street.

When did the practice start?

10 years ago.

How many staff?

70 people, based in London, Berlin and Sydney.

Company ethos?

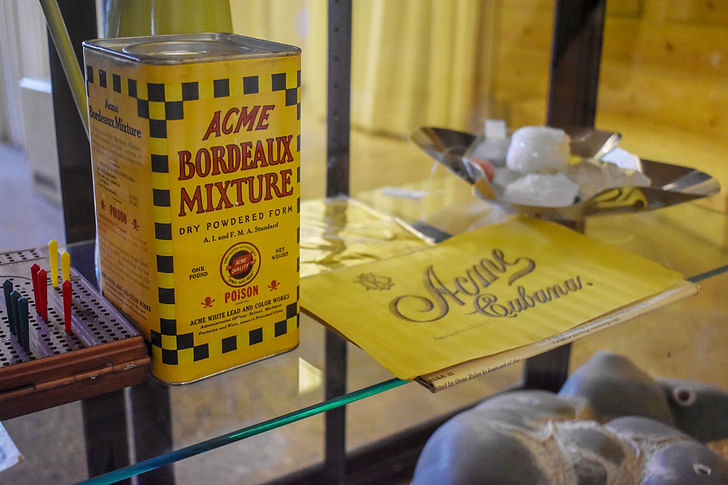

In terms of what ‘Acme’ means, and our reason for choosing the name, we felt it summed up our aspirations well; it stands for ‘the best possible’ in Greek, an acronym for ‘A Company Making Everything’, and lastly ‘Acme Corporation’ in the Road Runner, where the coyote keeps ordering all the really cool products.

As a business and as a practice we are very keen to do things that revolve around each individual place, we try to avoid one repetitive signature style. We really enjoy working in multi-layered, historic city centres, and in very different countries and cultures. People use familiar materials in very different ways wherever we go and we have been able to explore, learn and apply techniques and methods that were new to us, by keeping an open mind as to how things should be done. We aspire to be unashamedly contemporary while being also unashamedly vernacular, to create buildings that are quite specific to their place and make sense within their own context.

We aspire to be unashamedly contemporary while being also unashamedly vernacular, to create buildings that are quite specific to their place and make sense within their own context.

Our internal work ethos will continue to evolve. We have grown every year, and some things that worked well when we were 25 people get a bit more difficult when one gets to 70 people. All of us have come from different backgrounds, some from very large, corporate offices and some directly from university, so we all bring very different experiences and expectations to the office, and what it means to collaborate. We’ve tried to preserve a small office culture for some years, even when we got quite large, and we have learnt along the way that some elements are just not working anymore. We have become more professional in quite a few areas, from time off in lieu to internal reviews and communication, but it has been a long process, and often the subject of seemingly never-ending discussion. We still really enjoy informality in the way we work with each other, and to create a very nice place to work that is not too formulaic, but we are all getting a little older and are coming around to the benefits of more structure in our lives and to accept that not everything can be decided by debate and consensus.

Current projects?

ACME London are currently focused on five projects in the UK, Minories in London, Chester Northgate, Swansea Central, Folkestone Harbourand a timber office tower in Elephant & Castle. In Europe, we are spending quite a bit of time in Dublin for Moore Quarter and in France for projects in Marseilles and Toulouse. We are on site in Oman, and Jumeirah Central in Dubai is our largest project in Concept stage there. ACME Berlin is working on our Bank HQ in Leipzig, which has started construction, markets in Frankfurt and Munich and a large scheme in Prague. ACME Sydney is working on two large masterplans for Melbourne and Brisbane, a hotel in Sydney and a library in Perth.

We are finding increasingly that we don’t have be amazing in everything, we just need to be open minded to absorb what is best in each place and start to question and apply it elsewhere.

There are very different ways of working in diverse location, each has its own particularities. In Germany, architects are much more hands on, juggling architecture, project management and quantity surveying, and often there is no Main Contractor, leaving much more responsibility in the hands of the architect. In the UK, the role of the architect is smaller, and clients usually pursue Design and Built contracts, leaving us to work as members of the design team in collaboration with the main contractors to ensure that the project is detailed well. In Asia, we are delivering much more detailed construction information, as the supply chain is less experienced, and the role of the architect is more traditional.

Having worked internationally for the last 10 years, we are starting to use the experience gained elsewhere more and more in our work. Every country is brilliant in some things, and less brilliant in others. Australia is exceptional at food, they have great leasing teams there to work with young, entrepreneurial restaurateurs, and they are very good at office space planning. Germany is great at sustainability, low energy office design, complex facades and timber construction. France is great at deep, sculptural facades, the UK is much more open minded in regulations, and space optimisation. We are finding increasingly that we don’t have be amazing in everything, we just need to be open minded to absorb what is best in each place and start to question and apply it elsewhere.

The food markets that we are working on in Birmingham, Chester and Swansea are deeply influenced by the lessons we have learned in Brisbane, and that experience has given us a lot of confidence to push for solutions that would have been normal in Australia, but are considered ground-breaking here. In the office buildings we are designing in Melbourne, we have taught the locals a lot about a more German approach to sustainable service integration, which is new there. In the same vein, we have used the lessons we have learned about office space planning in Australia to make our German office clients more comfortable with open plan workgroup environments, which is considered quite radical in Germany. It is lovely that each of the places we are working in turns out to be very good at something, often unexpected, and they have developed a specific area of expertise which can be utilised, expanded and applied elsewhere.

Have you always been at this studio?

We started out 10 years ago in a squat, we took a temporary lease with a 4 week notice period, as the building was meant to be demolished shortly to make way for a Norman Foster office building for Amazon.

It was a space of 250sqm, we paid £4/sqft, which is ridiculously little in the City of London, and we didn’t need to have meeting room walls because we had so much space that we could just move the meeting room tables far enough away from our desks to have private meetings without anyone overhearing each other. We were keen to make it look professional, but as we were on a 4 week notice to vacate, we needed to find a way to make it look grown up but with a very small budget, that is how we came up with curtains to create walls and divisions, using 400sqm of fabric at £1/m. It is amazing how much stuff one can hide behind curtains while looking quite elegant. It not a new concept, Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich used it for their temporary Satin and Silk Cafe in 1927, but we only found that reference a bit later. In the end, our temporary installation lasted quite a while, we were in our original curtain space for four and a half years, before the Foster Building finally started construction. It was finally handed over to Amazon a few months ago. We got very used to the space and the curtains over the years, and we carried the curtain concept it with us to the new offices here and in Berlin, even though we don’t have as much space now as we used to have in the beginning, when we could cycle between desks!

Favourite part of the studio?

We are trying to persuade everyone to spend more time in the library, but getting people to use a book is getting harder.

We have used several parts of the office as places for experimentation. For example, we have tried to convince clients many times to make public toilets more interesting, as you don’t spend a lot of time there, it’s only a four-minute commitment! However, we keep losing these battles because clients get scared of something a bit more sensual or strong, so we have used our own toilet in the office as a mock-up, to test with materials, lights and mirrors how much confusion is interesting, and when it gets too annoying.

The staircase is similar, we had some structural issues and realised maybe that the existing concrete floors were not as strong as we thought they ought to be. We therefore designed our new staircase as a cantilever that doesn’t touch the floor above. We were keen to explore the possibilities of the stairs as a social space as well as a visual connection between levels. Coco Chanel installed a stair in her house in Paris that allowed her to people watch from above during her fashion shows, where she could gauge how people reacted to the clothes without being seen. We thought this was an interesting effect, to create a stair that shows you the life in the rest of the building, so we have experimented quite a bit with that effect on our own stairs.

When you see our current space from the street, it does not look much like an office, it’s looks a bit more like a decent coffee shop, with a good coffee machine, and a lot of different teas. I have always admired the offices of a Japanese architect who was sharing his space with his florist wife. How nice to walk into a florist that is also an architecture practice, smelling of model making and flowers at the same time, and confusing every client a bit. When I studied in Berlin, we rented an old Fishmongers shop with a few friends as a studio, and people would always wander into the shop from the street and inquire what we were selling, and we’d always try to sell them a house. We still enjoy this close relationship to the street and the daily life around us.

Do you eat lunch together?

A lot of people bring their own food in but most of us will sit and have lunch together downstairs in the ground floor. At some point in the future, we would love to have a cook to prepare lunch for everyone, and we have installed a hob and oven into our kitchen just in case, but we have never solved the extractor and smell question, so it’s parked for now.

Favourite nearby coffee shop?

We have spent a lot of time and effort on our own coffee, so people going elsewhere for coffee is always a source for concern. Kees van der Westen in Holland has built our coffee machine for the London office, and our friends from Ozone Coffee around the corner have managed to get both the machine and the grinder gold-plated, to match our traditionally golden kitchen. The Berlin office has a mighty golden brass Victoria Arduino machine which will be ready in the new year. Where to buy beans is a big question these days. The Australian coffee culture has arrived in London and Berlin over the last few years, bringing with it a much greater interest in the origin of beans, the strength of the roast and the freshness. We now have a great choice of local coffee roasters in the neighbourhood, and after much testing, we have agreed to go with Climpsons, who are supplying us with freshly roasted beans every two weeks, not too green and not too black. Every architect gets barista training when they arrive, to make sure their latte art is up to scratch!

Every architect gets barista training when they arrive, to make sure their latte art is up to scratch!

Pets allowed?

Pets are allowed. An ACME dog has been discussed more than once, but the question of who would be reliably looking after it over the Christmas holidays was not yet been satisfactorily answered.

Most played song/artist/musician?

People play music loudly over the speakers when they are alone in the office, or surrounded by just a few colleagues, but the times are over when we were small enough to agree on a musical direction. I’d vote for Electronica and J-pop but I am sure I’d be in the minority.

Favourite architect?

Different answers for different days. Alive or dead?

Alive in the UK?

I have enjoyed working with David Chipperfield in the moments where we have collaborated, and we are fans of the Mexican Gallery, Wakefield, the Berlin New Museum Entrance that is about to complete. Caruso St. John’s bank in Bremen is great, as is Niall McLaughlin’s chapel in Oxford. We admire Foster for the ability to grow to 1500 people and still produce buildings like Bloomberg, and Rogers Airport in Madrid remains a delight to use, quite the opposite of their T5 in Heathrow.

Dead in the UK?

Apart from the usual Sloane and Stirling, we have been looking recently a lot more at Basil Spence, Slough, Powell & Moya, Ahrends Burton & Koralek, Lasdun and Seifert.

Others?...

We look up to quite a lot of Japanese, Swiss and Spanish architects. But more than anything else, we admire practises such as OMA, Herzog de Meuron or Sanaa for their ability to not repeat themselves. Not every building needs to be brilliant, but each seem to have found their own way to question everything anew, challenging themselves and not repeating what they have done before. For example, HdM have done five or six stadiums by now and each one takes something from the previous ones but ultimately offers something completely new. To be able to question typology and oneself every time again is what we admire the most.

The current architectural production has been very restrained, rarely questioning typologies, and we are in danger of going through another construction boom cycle without much work of lasting architectural value or relevance or innovation to show for it.

Favourite building in London?

Current favourites include a lot of 1950s/ 60s architecture like the Barbican, Alexandra Road, and some of the great estates of the 18th century around Bloomsbury, Regents Park and Chelsea, which are a fascinating way of working with small identical private houses to create something public and much larger than any of the constituting elements. We think we are not the only architects currently re-evaluating the optimistic buildings of the 1960s and 70s. There are interesting parts of our architectural history that are still severely undervalued in this county. The optimism and fearlessness of the time puts most of the work currently in progress in London to shame. The current architectural production has been very restrained, rarely questioning typologies, and we are in danger of going through another construction boom cycle without much work of lasting architectural value or relevance or innovation to show for it. We look forward to some of the new buildings going up in the City, and some of the new residential quarters such as Canada Water or Brent Cross, and we hope they will not be missed opportunities to create buildings and places as innovative in their own ways as the ones created by architects in London 50 years ago.

Ellen Hancock studied Fine Art and History of Art at The University of Leeds and Sculpture at Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University in Istanbul.Now based in London she has a keen interest in travel, literature, interactive art and social architecture.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.