"Here is the Palace of the People. Here is its armament. The struggles of the future will not be determined by the sword and flaming torch, but the knowledge, education, and the ballot."

These words were delivered during the dedication of the Chicago Public Library on October 9, 1897 by Corporation Council’s Charles S. Thornton. Two days later, the building would open its doors to the public, nearly twenty-six years to the day after the Great Chicago Fire.

More than a century later, in October of 2015, the same building became the main hub of the inaugural Chicago Architecture Biennial and it was the first time that the entire building had been dedicated to a single event. The event brought the well-known Chicago structure, now known as the Chicago Cultural Center, renewed attention from new audiences and a chance to repurpose some of its lesser-used spaces.

Between its original opening and the Chicago Architecture Biennial, there is a long and complex history, making the structure a symbol of the ambition, wonder, politics, and challenges that buildings in Chicago face.

To learn about the history of the Chicago Cultural Center I met with Tim Samuelson, Chicago’s cultural historian since the late Lois Weisberg—then Commissioner of the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs—created that position for him in 2002. A city treasure in his own right, Samuelson has been involved in local preservation efforts for nearly his entire life, and played a significant role as part of the city's Commission on Chicago Landmarks in the 1980s. In 2015, Landmarks Illinois named Tim himself a “Legendary Landmark."

Outside his office, located on the fifth floor of the building he has helped to restore, visitors are welcomed by a large sign saved from The Grand Terrace, originally known as the Sunset Café, a legendary jazz club in the Bronzeville neighborhood that Samuelson helped landmark in the late 1990s.

Stepping into his office is stepping into the history of Chicago, where all sorts of artifacts (including Elliot Ness' handcuffs), books, comics, photographs, maps, and sculptures coexist. The well-known cartoonist Chris Ware, a longtime friend and collaborator of Samuelson, says that his office is "one of the finest museums in Chicago."

In order to understand the building we need to look at the history of the Chicago Public Library itself. The history of libraries in Chicago can be traced back to 1834, three years before the incorporation of Chicago as a city, when the Chicago Lyceum created a circulating library for its members consisting of 300 books.

With the aim of creating a public institution after the Great Chicago Fire destroyed the private libraries that had appeared in the previous decades, the City Council passed an ordinance establishing the Chicago Public Library in April of 1872. Just a few months later, on New Year’s Day, 1873, the first Chicago Public Library opened its doors with 8,000 books donated by British authors as the base of the collection after the catastrophe.

Its first home was a 60-foot diameter and 30-foot high circular iron water tank that had survived the Fire located atop a masonry building on the southeast corner of LaSalle and Adams in the Loop—the famed Rookery site where City Hall was temporarily located. It was the first of several makeshift homes the library would occupy during the following two decades.

Frederick H. Hild, the second librarian of the Chicago Public Library after William F. Poole resigned to lead the Newberry Library, was elected chief librarian in 1887 at the age of 28. He focused on securing a permanent home for the Chicago Public Library, lobbying influential citizens and politicians aided by the impetus provided by the upcoming World's Columbian Exposition of 1893. The City Council granted the required approval that year to locate a new building at Dearborn Park.

It was no ordinary site. Part of the old Fort Dearborn grounds, it had been the center for political speeches—including one in 1856 by future president Abraham Lincoln. As the state legislature had already given the north quarter of the park to Soldier’s Home, an American Civil War veterans organization, the new building would ultimately serve two purposes: home of the Chicago Public Library as well as a Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) Memorial Hall dedicated to the soldiers and sailors from Illinois who served in the Civil War.

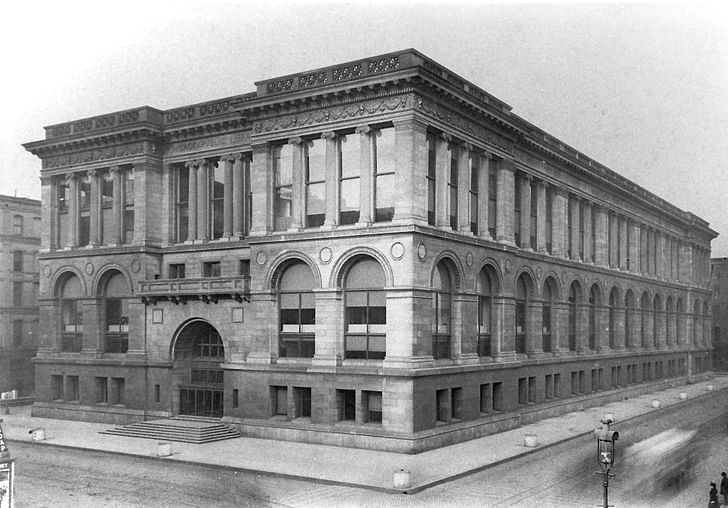

In February of 1892, a nationwide search resulted in a commission from familiar face: the Boston-based firm of Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge, who were already working a few blocks south on the Art Institute of Chicago. Rather than request philanthropic support , the City Council imposed a 1% tax on all Chicagoans to finance the new building . Symbolically and literally, the new public library belonged to the people of Chicago. Five years later, the building opened, symbolizing the sophistication and cultural renaissance of the city, something achieved with the help of two other institutions: the Newberry and John Crerar research libraries. Chicago was no longer just a city of stockyards and smokestacks.

The five-story structure was designed to look like a large three-story building with a series of compositional and visual tricks. Originally U-shaped, it featured imposing three-foot thick walls made of Bedford Blue limestone on a granite base. A series of medallions, similar to those found at the Art Institute of Chicago, are located above the arched windows were never completed. Samuelson pointed out that, “each one of the medallions was going to be carved back on site into printers’ marks. It never happened and what you have now is a big circular piece of stone sticking out. Similarly, the keystone in the arch over the Randolph Street entrance is rough. That is not for any kind of artistic effect. They never finished it.”

Inside, the grand staircase off of Washington Street led into the impressive Preston Bradley Hall, which served as the general delivery room of the library and included a white oak counter spanning the width of the room. Its most impressive feature, however, was the 38-foot diameter translucent dome made of Tiffany Favrile glass cut in the shape of fish scales. Jacob Adolphus Holzer, who was also responsible for the exceptional mosaics found across the building, designed the dome. Quotes in ten languages reminded its users of the public and inclusive character of this “Palace of the People.”

Opening a copy of the Inland Architect Supplement published in 1898 and dedicated exclusively to the Chicago Public Library building, Samuelson walks me through the different spaces: the reading room, now the Sidney R. Yates Gallery, was located on the fourth floor. Accommodating 340 patrons, the room was lit by impressive 7-feet wide by 23-foot high windows. The Chicago Rooms on the second floor originally held three-tier stacks of shelves over a glass floor where books were stored. Among other programs, the library included a reference room, a library for the blind, a newspaper room, rooms for government documents and patents, and a bookbindery.

“The building had two distinct zones. [Frederick H. Hild] firmly believed that the areas of the building where the books circulate and are taken out had to be separate and as far away as possible from the reading rooms. He wanted to keep the noise separate. It was a closed library where you could not browse the shelves. This was an approach that Mr. Hild had inherited from Mr. Poole,” said Samuelson.

As for the GAR, the building’s other tenant, their facilities on the second floor included the Memorial Rotunda, a museum overlooking Randolph Street that included Civil War relics and flags, and an auditorium—now the Claudia Cassidy Theater. In 1948, the Chicago Public Library took possession of these spaces with the GAR formally dissolving in 1956 after the death of the last member. The artifacts are now housed at the Harold Washington Library Center.

Throughout the building, green-veined Vermont marble, Knoxville pink marble, and white Carrara marble were used along with polished brass, fine hardwoods, and colored stone to impress and uplift patrons. It was a demonstration of the ambition, quality, and wonder that Chicago could offer culturally and architecturally.

Despite its distinctive qualities, the library’s needs had already outgrown the building by the 1930s. In the following decades, the situation did not improve and, by the 1960s and early 1970s, it faced the threat of demolition, with developers receiving a tentative approval to demolish it to build an office building. In the name of progress, other notable structures in the city were also battling the threat demolition at the time such as the Reliance Building, the Marquette Building, and most notably the Old Chicago Stock Exchange that would ultimately lose that battle and was demolished in 1972. Architectural photographer and preservationist Richard Nickel, a mentor to Samuelson, lost his life during the demolition.

An eight-year preservation campaign, the revolt of the building staff, and the "I don't think that would be nice" response by Sis Daley, wife of Mayor Richard J. Daley, to a reporter’s question regarding the building’s possible demolition, ultimately saved the building and helped to place it on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972. But it was clear that the future of the Chicago Public Library and that of the building itself would part ways moving forward. In 1974, part of the library’s collection moved to the now demolished Mandel-Lear building—originally the Hibbard, Spencer, Bartlett & Co. warehouse designed by Graham, Anderson, Probst & White—splitting the collection between the two facilities. Simultaneously, the building then underwent a three-year renovation led by Holabird and Root, updating the facilities while adding a new portion to the building, turning its original U-shape into a full ring.

In 1977, the Chicago Public Library Cultural Center, as it was renamed, opened its doors once again. Spaces were reorganized and repurposed, turning areas dedicated to store books into exhibition areas. Despite the changes, its public character remained intact. Among the many exhibitions held in the new space, Tim Samuelson recalls "Flip! Flash! Pinball Art," curated by Chicago artist Ed Paschke in 1982 featuring a vast selection of pinball machines since the 1950s, Chicago being the center of pinball manufacturing.

This was also the period when many who did not live in Chicago discovered the building through Brian De Palma’s 1987 prohibition thriller, The Untouchables, which made extensive use of it for many of its key scenes. "This is where Kevin Costner [as Elliot Ness] stands when he arrests Frank Nitti before pushing him to his death from the roof,” Samuelson points out right outside his office.

As for the fate of the library, a design/build competition organized in 1987 and won by architects Hammond, Beeby & Babka led to the construction of a new Central Library located on State Street between Congress Parkway and Van Buren Street. The postmodern Harold Washington Library Center opened in 1991, becoming the world's largest municipal public library at the time. It featured the remarkable Winter Garden public space on the top floor and once again provided a permanent home for the library collection.

The Chicago Cultural Center, as the building has been known since the last remaining books were moved to the Harold Washington Library Center, is still a place where residents and visitors of all ages and economic means gather to enjoy the free activities offered daily. People come to see exhibitions and concerts, get married, or just meet at the gathering room off of Randolph Street—known as Randolph Square—to talk, have lunch, work, play games, or use the free WI-FI.

Samuelson maintains that the beauty of the Chicago Cultural Center, not being a formal museum, is that they can experiment with events and exhibitions that push the envelope. “We have always had staffers who were willing to try things. We show artists and content that a traditional established museum would never do. I don’t know anything quite like it,” he remarked.

Samuelson’s fondest memory in the building was a concert by jazz musician Kelan Phil Cohran on Halloween of 2013. "One of the best concerts I have ever seen was in this building. It was the late Phil Cohran with his family and his company playing in Preston Bradley Hall. Phil wore his full Egyptian headdress and whatnot, and we were able to turn all the lights down. It was absolutely magic. It was the most wonderful thing I have ever seen here.”

He loves how the building successfully becomes the backdrop for so many different activities. “For all the opulence of the building, when you have strong, dynamic, and powerful people performing in a room, the building nicely steps back as a beautiful backdrop for them. It doesn't overwhelm it as you think it would. Somehow, it works well.”

As Samuelson gives me a tour, we run into Mark Kelly, Commissioner of the Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events since last August, whose office is also located in the building. Kelly points out that the Chicago Cultural Center has never had a mission statement or master plan, something that he is addressing and that he expects will reshape the building. “Going forward, the Chicago Cultural Center becomes ground zero for Chicago’s cultural life. We move away from being the programmers to become the host, connecting the audience to Chicago’s cultural landscape. It now becomes the Millennium Campus, with this building being the interior space and Millennium Park the outdoor space, all with the same purpose.”

Beyond its free public programming, the Cultural Center is home to civic initiatives such as After School Matters, StoryCorps, Chicago Children’s Choir, Renaissance Court Regional Senior Center, as well as the Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events (DCASE) and the Chicago Architecture Biennial.

The reinvention of the Chicago Cultural Center as a hub for the Chicago Architecture Biennial shows its capacity to not only adapt to new uses but to elevate them to create a better experience. The success of the inaugural edition of the Chicago Architecture Biennial was arguably the result of the content exhibited as much as the unparalleled setting. For Samuelson, “this building is all about creating a very special and beautiful place for everybody. This is the one building in the city where the doors were open to absolutely everybody who walked in. If you came here to read, learn, or just sit in the building, you were welcome. And that certainly wasn’t the case throughout the city when it was built. It was always about having an open door. And that has stayed consistent.” Embracing a combination of daily routines and planned destination, the Chicago Cultural Center continues to be the Palace of the People more than a century after its opening, even if the books are long gone.

Bio Author

Iker Gil is an architect and director of MAS Studio, an architecture and urban design firm based in Chicago. He is also the editor in chief of the design journal MAS Context and the editor of the book Shanghai Transforming (ACTAR, 2008). He is a faculty member at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s Department of Architecture, Interior Architecture, and Designed Objects (AIADO). In 2015, he curated the exhibition BOLD: Alternative Scenarios for Chicago included in the inaugural Chicago Architecture Biennial.

www.mas-studio.com

www.mascontext.com

How much do you know about Chicago’s lost buildings? Explore more demolished Chicago and add your own examples to the Biennial’s Are.na channel below:

Iker Gil is an architect and director of MAS Studio, an architecture and urban design firm based in Chicago. He is also the editor in chief of the design journal MAS Context and the editor of the book Shanghai Transforming (ACTAR, 2008). He is a faculty member at the School of the Art Institute of ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.