As the founder of PAU, Vishaan Chakrabarti is an architect and urban planner who considers every aspect of the city with foresight, but isn't as concerned with the culture of celebrity that has often dominated the profession. "Calling oneself a humanist over the last couple of decades was a real no-no," he explains via phone. "You're supposed to be a bad-boy, cape-wearing starchitect." He purposefully did not name the firm after himself in order to place emphasis on intelligent discussion, not hierarchy. Although he's excited about taking on more projects, he never wants PAU to grow beyond roughly 30 employees so that he will always know everyone in his office.

This kind of humanistic approach has resulted in PAU undertaking massive, if often nondisclosure-agreement-bound projects that are designed to benefit existing cities by revitalizing neighborhoods and sites that other architects tend to write off. This process is more than slapdash gentrification: Charkabarti's understanding of the city goes beyond maximizing developer dollars per square foot, and centers instead on representing the past while planning for the future in a process he describes as learning to "read the city." He wants to make our environments livable, which means connecting people and industries in a holistic, sustainable way. In this interview, we discussed some of PAU's current projects, the kind of work Chakrabarti purposefully avoids, as well as his distinctive thoughts on density.

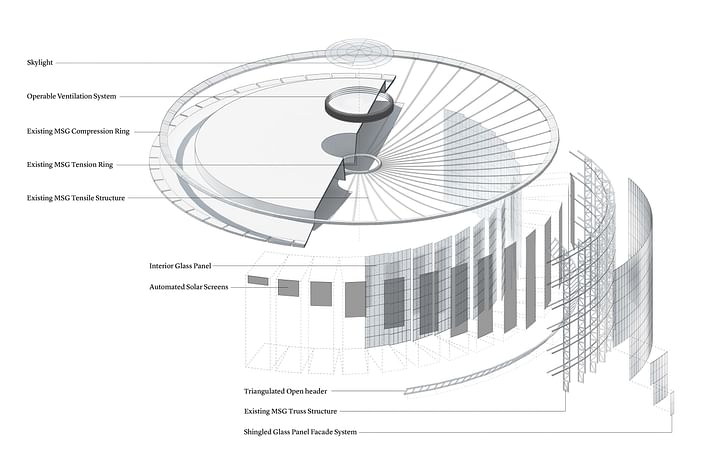

In the nearly two years since you started PAU, the most prominent project you’ve put forward so far is the proposed Penn Station transformation at the request of The New York Times, which basically eliminates the current warren of low-ceilinged corridors by moving Madison Square Garden and transforming that space into a glassed-in, 150 foot ceilinged entryway to the transportation infrastructure below. Is that proposal any closer to becoming a reality? What has the reaction been?

Cities are almost never tabula rasa, they’re not these sites in the middle of the desert where you get to build your spaceship with slave labor

The reaction has been very positive, generally speaking. The Times likes it a lot. The regional planning association and other fairly prominent civic groups are very interested in it. I get asked to do quite a lot of presentations on it—I did two presentations last week. The main decision makers are obviously the governor and Madison Square Garden, and you know I’m cautiously optimistic. Certainly no one has adopted the plan, but I think the plan has really helped to put a spotlight on a situation that is increasingly getting worse. Because there was the stampede a couple of months ago, there have been a number of really bad incidents at Penn, and this summer there’s a track that will be shut down, it’s going to be very congested there. So there’s a lot of tough news for commuters. There’s some good news too: The West End concourse opened under the Farley Building, which is a different exit path for the trains to the West, which I think is an improvement. And I think the governor is clearly trying to make as many improvements as he can, and I think he’s worried that something as big as we’ve proposed would slow things down. Having worked in government, I’m very sympathetic to that viewpoint, that sometimes you don’t want the perfect to get in the way of the good. I also think that what we’ve proposed is phaseable. You can do what they’re doing right now, and then do what we’re proposing as a next step. I don’t think anyone has formally adopted the plan, but no one I’ve shown the plan to objects to it on its merits. I think the only questions about it are the standard questions of timing and approval and funding. For me, stepping back, for our office, it was a fascinating thing to have happen.

Bringing density and life and activity, especially residential density, back into the heart of Newark is something the mayor of Newark is very focused on

The office is now 10 people: we have a lot of work. But I can’t put any of that work on my website because it all has a nondisclosure agreement on it! Some things have been announced, so I can tell you the kinds of things we’re doing. The city just awarded us Mart 125, which is a small cultural building that’s a restoration of a building that exists. It’s on 125th street directly across from the Apollo Theater in Harlem. And that looks like it will be a very interesting cultural space, and we very much want to do cultural projects. That is really terrific, I think it’s an important project for Harlem. We’re working, along with Two Trees, on the Domino Sugar Refinery which is a landmark on the Williamsburg waterfront. We’re basically working to convert it into a tech office building, a kind of incubator space. That’s a process where we’re inserting a building into a building. In both cases, what’s wonderful is that we’re enjoying working with the existing urban fabric. It’s consistent with our mission of advancing cities. Cities are almost never tabula rasa; they’re not these sites in the middle of the desert where you get to build your spaceship with slave labor. It’s this thing where you really have to deal with the forces of the city and material qualities.

Since we can’t get into specifics, I’ll state a broader observation of your body of work, which is that it seems like you’re always keen to reinvigorate the urban fabric. There are trends in development in dense urban areas like New York, which involve all of these hermetic, crystalline towers shooting up into the sky—

[Laughs] Yeah, we’re not doing any of those. We’ve turned a couple of those down. A good friend told me that a lot of who we are in the world will be defined in the world not only by the jobs we take on, but the jobs we turn down. I believe in density. We’re doing a housing project in Newark I can tell you a little bit about. It’s a fairly large project; we did the master plan for the seven-acre site, and now there are three different architects, and now we’re working on the actual design of the buildings. The one we’re working on is fairly large; it’s not a big glassy tower.

Roughly how many units of housing are you going to have on these seven acres?

Over 2,000, and I think it’s really important for Newark. The central core of Newark only has about 4,000 residents, because it lost a lot of population after the riots and the industrialization. So bringing density and life and activity, especially residential density, back into the heart of Newark is something the mayor of Newark is very focused on, as well as the central stakeholders of the city, which includes the NJPAC and Rutgers. Everyone wants more residents there to create more street life, more shopping, and make the place feel as safe as possible. It’s got great transit infrastructure, the airport is right there. Sarah Vaughan was born in Newark. It’s a great place, and it’s 15 minutes away from Manhattan. And yet for most Manhattanites, it’s a world away.

I think of architecture as an act of writing in the city. And you can’t really do that if you haven’t read it

Another thing that’s interesting about the practice, and this is true of a site we’re working on in San Francisco as well, is that we’re working on what I think of as 'drive-by' sites. They are sites that you drive by on the way to the airport. So much of the profession has been doing luxury condos in the center of the city or, like I said, spaceships in the desert somewhere. But when they’re in their Uber going past places like Newark and parts of Brooklyn and Harlem, those are the places I’m actually interested in. There’s a kind of an inner ring to most cities that’s been neglected for years. It got de-industrialized, it got poorer, it became a place of lot of racial strife. The site in San Francisco is a former power plant site, between the airport and downtown. It has a really tragic social history. The place has been neglected by the profession. For us it’s super interesting, and like you said, we really work on re-knitting these sites into the fabric and not isolating them.

Something I say to my team is that you have to be able to read the city in order to write in it. I think of architecture as an act of writing in the city. And you can’t really do that if you haven’t read it. For me, that goes way beyond this idea of context. It’s not a superficial read of the city; it’s not, ‘Oh, there’s limestone here, we’re going to put more limestone there.’ Materiality is important, of course, but reading the city tackles larger questions: like block size, or infrastructure, for example.

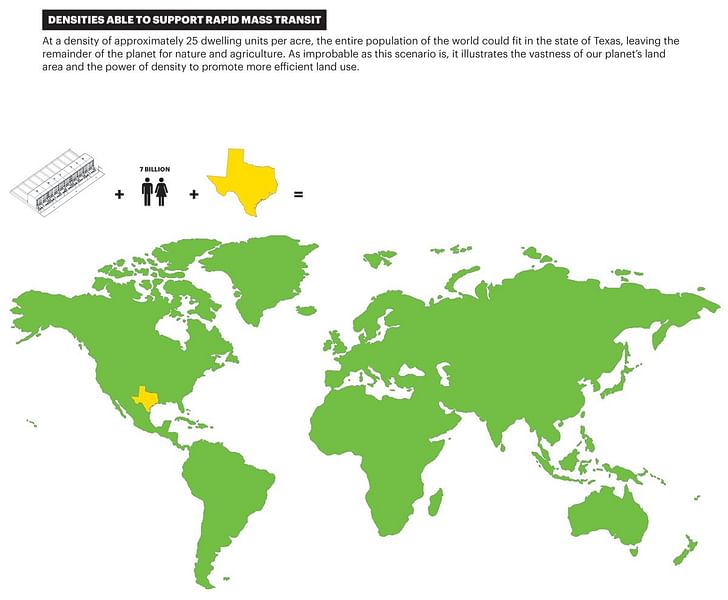

You have famously said that if we built a 25 dwelling units per acre, everyone on the face of the earth could live in Texas—not that you’re suggesting that we should all live in Texas. I’m curious, in terms of density: what type of structures did you live in as a kid?

What an interesting question! I was born in Calcutta, and we used to live in my uncle and aunt’s house in North Calcutta, which is pretty dense: pretty interesting spatial structure to the streets and so forth. I left there when I was very young; we went back and forth a lot, which is why I feel like I still know it. We were in Arizona for a while, and then we moved to suburban Boston, which is where I grew up. I hated every minute of it. I found it incredibly isolating and incredibly boring. We would spend our summers in India, and even when we arrived, in the 1970s, it was stiflingly hot, there was a lot of poverty. We would we would get in a taxi to go back to our house in the Boston suburbs, it really felt like a neutron bomb had gone off. Everything was so still and quiet in a bad way. There was no friction. For me, I’ve always said that the first time I came to New York it was like meeting a twin brother I never knew I had.

the new has to take on a certain sense of responsibility to the old

My book [A Country of Cities: A Manifesto for an Urban America] came out in 2013 and I was asked to speak on density in many different parts of the world. I’ve noticed a very palpable shift in this conversation. Three years ago, the debate was 'should we have more density in our cities? Is that the right path for us?' That is now a concluded question for most communities. Most communities are at some level embracing density more. Not so much a place like San Francisco, where it’s harder to make the case for density, but generally speaking, people are much more interested in the how, not the whether. Going back to your glass tower comment, one of the most common questions I get is ‘We accept that a denser city is a better city, we want more people in our city, and the structures to serve those people, but we don’t want these nameless, faceless buildings that really look like they could go anywhere.’ So, one of my real aspirations for the studio and something that we talk about as a group a great deal, is: how do you read a place, and make it understandable? Even if a new thing is coming that is of a larger scale, how does it feel like it belongs there? Architecture is being accountable to the community that is built. Part of that accountability is, ‘Does it feel like it belongs?’ That’s not an argument against the new, by the way. It’s just that the new has to take on a certain sense of responsibility to the old.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.