Architects are collectors. Collectors of different images, objects, ideas and other architectures. What we collect, and how we decide to put the different parts of this collection together, ultimately constitutes the architectures we make.

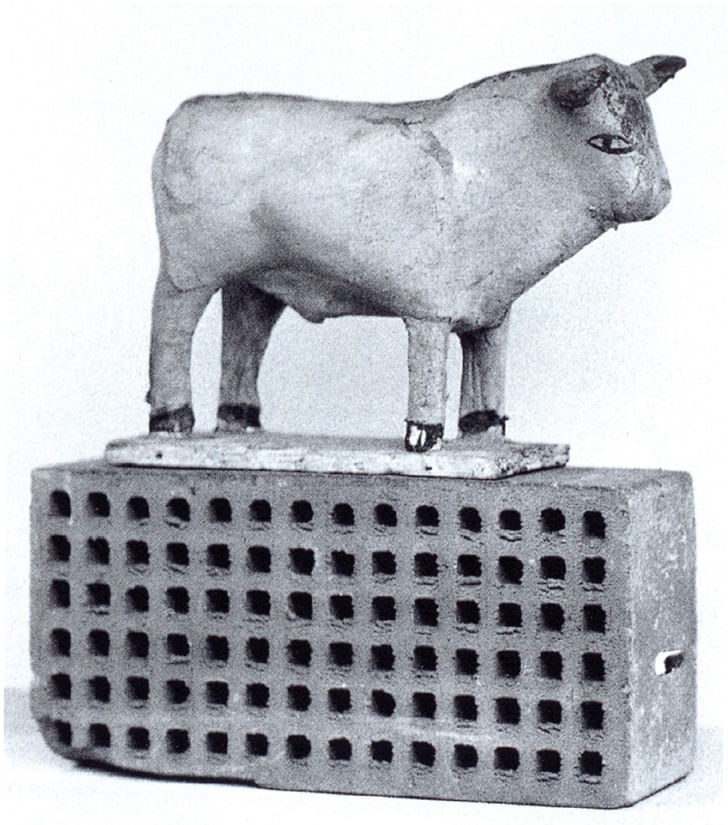

“La maison sur la maison”, a small assemblage by Le Corbusier—a great collector himself—that was part of his Collection Particulière comes to mind. In a manner that reminds us of the sculptures and assemblages of Picasso or Duchamp, Le Corbusier puts together, with a particularly beautiful crudeness, the figure of a bull on top of a brick. In doing so, this little sculpture is not preoccupied with achieving unity. Rather, it speaks to the richness that placing together seemingly incompatible parts can bring about. The artificial and the natural, the rational and the visceral, the passive and the active, the ordinary and the monumental… are all contradictory forces at play in this small composition.

Inescapably, to talk about architecture today is to address the collective, shared, and different natures of our societies and of a world in which knowledge, people, matter, and energy are forever being exchanged and mixed. In other words, they are perpetually reassembled, generating ever-newer relationships.

However, we mustn’t confuse difference with diversity. Establishing differences means establishing a tension, a clash, a series of exchanges and interactions, a direction for flows. Difference makes it necessary for the architecture to create a dialogue and a relationship between its parts—not to have them simply coexist together. It’s not concerned with portraying unity because our environment and surroundings are ever more entangled. Rather, a space where differences can emerge and engage productively is relevant now more than ever. One in which opposite parts can benefit from one another. Culturally, programmatically, socially, and energetically.

By giving value to different parts simultaneously and allowing them to clash and contrast, architecture does not need to take sides or assert truths. Rather, it establishes a territory that is for everyone and no one at the same time, a place for understanding as well as for disagreement. In its indifference towards the result of its process of assemblage, the architecture becomes open and creates a sense of liberation for the architect. In its openness it leaves space for the unpredictable and even the unconceivable, for people to read and misread it, and for life to unfold beyond any original architectural intentions.

This small and graspable manifesto in the form of a bull on top of a brick speaks to the beauty of architecture as a permanent place of conflict, one based more on differences than on elements of consensus, and in which value and innovation comes from the rough plurality of the things it brings together.

Cross-Talk is a new recurring series on Archinect that endeavors to bring architectural polemics and debate up-to-date and up-to-speed with the pace of cultural production today. Each installation will feature four responses by four writers to a single topic. For this week's iteration, the topic is 'agonism', a political theory that has begun to enter the architect's lexicon. Championed, in particular, by the political theorist Chantal Mouffe, 'agonism' asserts that productive conflict, rather than consensus, produces democracy.

Sofia Blanco Santos is a Spanish licensed architect graduated from the Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura in Madrid (ETSAM) and from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design with a Masters in Architecture II degree with Distinction receiving the Faculty Design Award and ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.