On the night of November 9, 1938, members of the Sturmabteilung, the Nazi paramilitary force, and German citizens took to the streets, smashing the windows of Jewish-owned businesses and destroying over 1,000 synagogues. At least 91 people were murdered and some 30,000 Jewish men were sent to concentration camps. One of the synagogues destroyed that night, now known as Kristallnacht, was in the city of Ulm, along the River Danube. Just over 70 years later, the architecture studio kister scheithauer gross architects and urban planners (ksg) was tasked with building a new synagogue on the site, which would both enshrine its history and look towards the future. We got in touch with ksg to hear more about the project.

What was the history of the site and of the project?

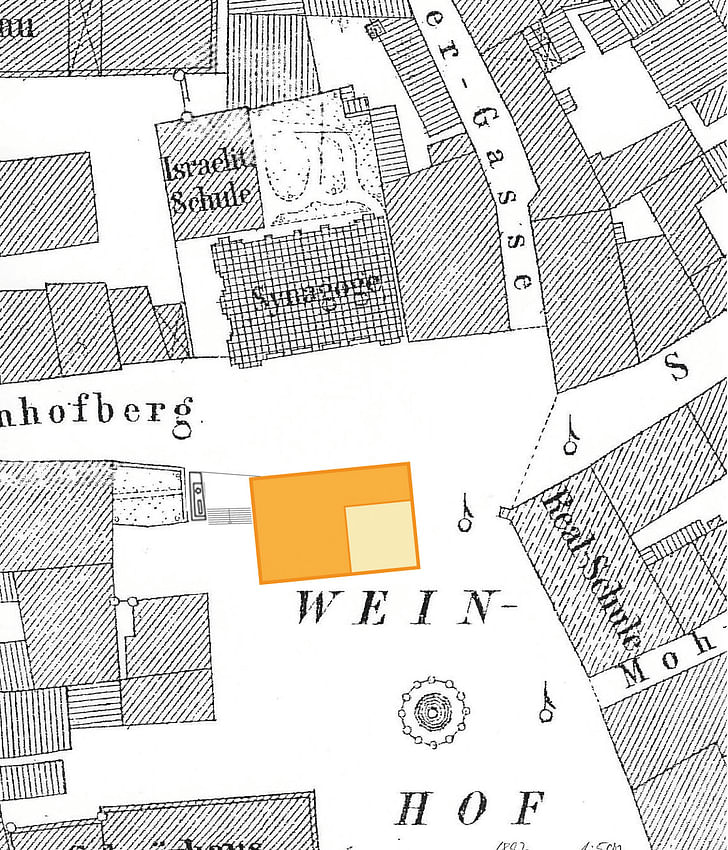

In 2009 the Israelite Religious Community of Württemberg statutory corporation (IRGW) decided to build a new synagogue for its community in Ulm, and so initiated a competition in partnership with the city of Ulm for the construction of a community centre with a synagogue. The city of Ulm benevolently supported the building project and made a building site available in the centre of the Ulm Weinhof, just a stone’s throw from the former synagogue, which was destroyed on Kristallnacht.

On January 21, 2010, it was decided: the competition jury, under the direction of Prof. Arno Lederer, unanimously chose the design by kister scheithauer gross architects and urban planners (ksg). “The team from Cologne succeeded in enriching this highly sensitive location in the city of Ulm, without detracting from its unique character,” said the city’s head of construction, Alexander Wetzig. A total of ten architects were invited to join the competition.

This position is historical: on the Kristallnacht in 1938, the former synagogue was destroyed.Subsequent to the competition success, the design was altered according to some proposals from the jury and the Rabbi. On February 8th 2011, the Ulm city council gave its approval for the altered design of the synagogue, again with a unanimous vote. The cuboid is now lower and shorter than originally planned during the competition. It now measures 24 meters in width, 16 meters in depth and, at 17 meters high, is significantly [shorter] than the nearby Schwörhaus.

The ground-breaking ceremony was held on March 17, 2011. Together with the IRGW representatives, the mayor of Ulm Ivo Gönner and minister Yossi Peled as the Israeli representative, Prof. Susanne Gross opened the site. Just twenty months later, the building has been completed and the new community centre with synagogue was ready for the celebratory opening ceremony. The building was full to capacity during the opening on Sunday, December 2, 2012. The 300 invited guests included former Jewish citizens of Ulm, who fled during World War II. Speeches were held by Federal President of Germany Joachim Gauck, Prime Minister of Baden-Württemberg Winfried Kretschmann, the President of Central Council of Jews in Germany Dieter Graumann and Israel’s ambassador to Germany Yacov Hadas-Handelsman.

How does the project respond to its historic context?

The synagogue and the Jewish community centre are contained in a single structure. The compact cuboid is free standing in the square. This position is historical: on the Kristallnacht in 1938, the former synagogue, which was enclosed in a roadside development, was destroyed. After World War II, a secular building was constructed in the space. The synagogue and the Jewish community lost its ancestral place in the centre of Ulm.

The construction of the current synagogue has opened a new site in the middle of the square, the Ulm Weinhof. It is as though the synagogue has taken a step forward from its former position; it has reclaimed its location. With no constructed border, it stands abrupt and solitary on the Weinhof.

Can you tell us about aspects of the design that recall or were inspired by traditional

Jewish iconography and architecture?It is as though the synagogue has taken a step forward from its former position

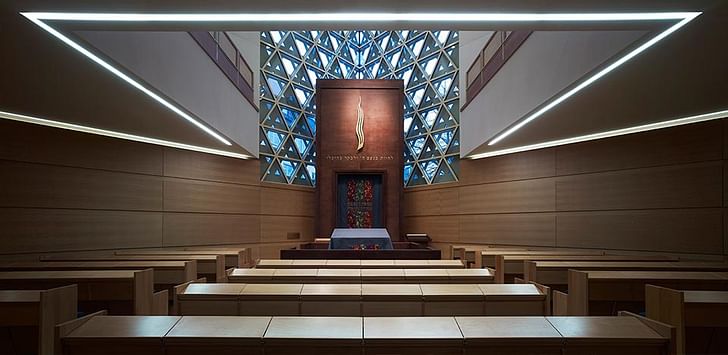

Inside, all the rooms are organised orthogonally, with one exception: the prayer room as the actual synagogue. The long side of the sacral room stretches diagonally across the room in one turn around the only, free-standing interior building support. The position of this space diagonal has an overlying religious meaning; its geographical direction is directly towards Jerusalem, the spiritual and religious centre of Judaism.

The diagonal room layout creates a corner window in the sacral room, which plays with a pattern of the Star of David as space framework. With 600 individual windows, the space in the synagogue is illuminated from many points, with the Torah case as focal point in this spiritual centre. At dusk, the pattern is also projected outwards by inner lighting, clearly but simply indicating the building’s purpose.

The Torah case is in the corner of the synagogue room which faces towards Jerusalem. In front of it is the bimah, a raised platform with a lectern, from which the Torah scrolls are unrolled and dictated. These two liturgically functional elements were made in Israel, under the Rabbi’s direct instruction. A further custom made item is the dodecagonal chandelier, symbolising the twelve lines of the people of Israel. The 3.30 meter wide chandelier floats over the bimah and seating.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

1 Comment

Beautiful project. Well done.

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.